|

Vittorio

Rieti, Prolific Composer In Neo-Classical Style, Dies at 96

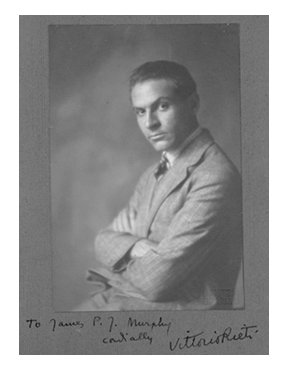

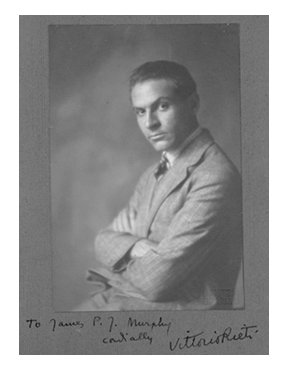

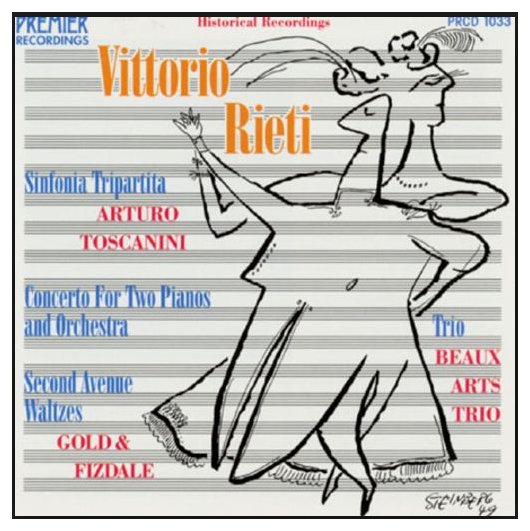

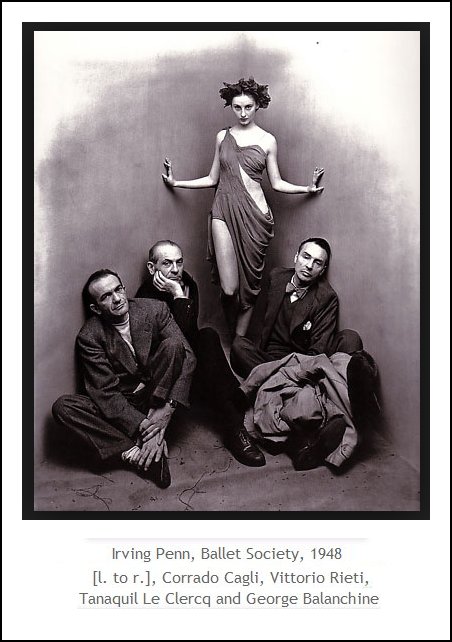

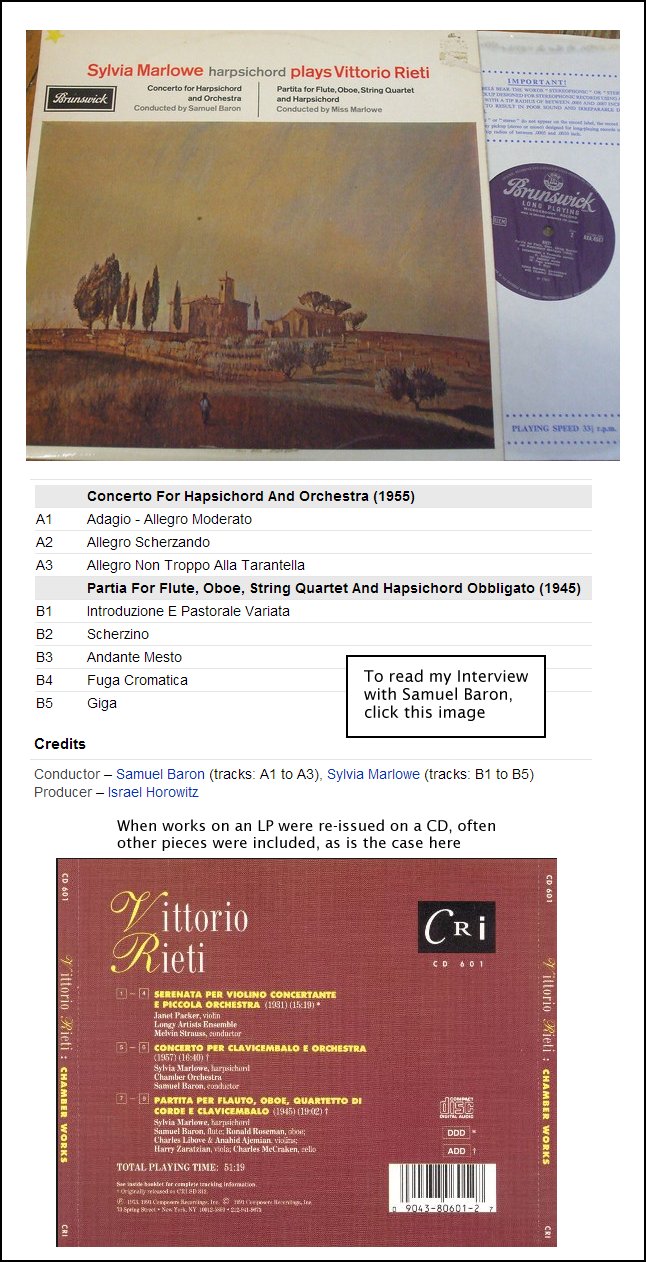

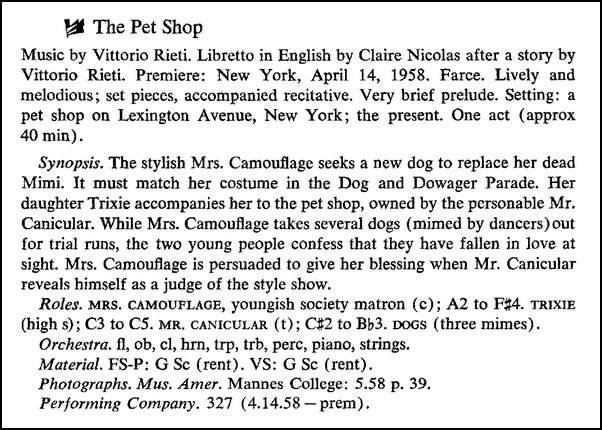

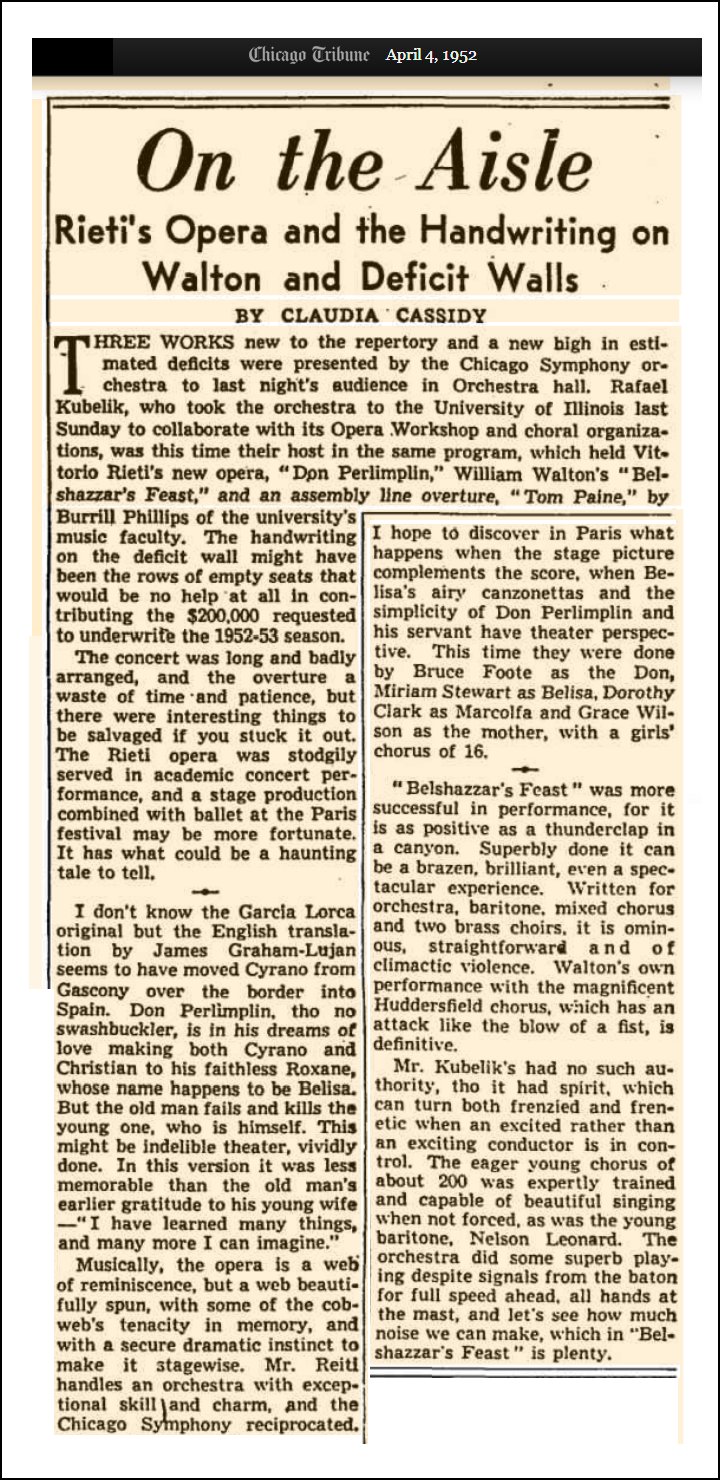

Published in The New York Times, February 21, 1994 [Text only - photos added for this website presentation] Vittorio Rieti, a prolific American composer who fashioned bright, elegant Neo-Classical scores for the ballets of Serge Diaghilev and George Balanchine, died on Saturday at Mount Sinai Medical Center in Manhattan. He was 96 and lived in Manhattan. The cause was not immediately clear, said his son, Fabio, but Mr. Rieti had suffered a bad fall at his home, breaking several ribs. In a career that spanned eight decades, Mr. Rieti wrote music for more than a dozen ballets, seven operas, five symphonies, several concertos, chamber music for a wide variety of instrumental combinations, songs and choral works. His music was widely performed; among the conductors who led performances of Mr. Rieti's works were Fritz Reiner, Frederick Stock, Willem Mengelberg and Arturo Toscanini.

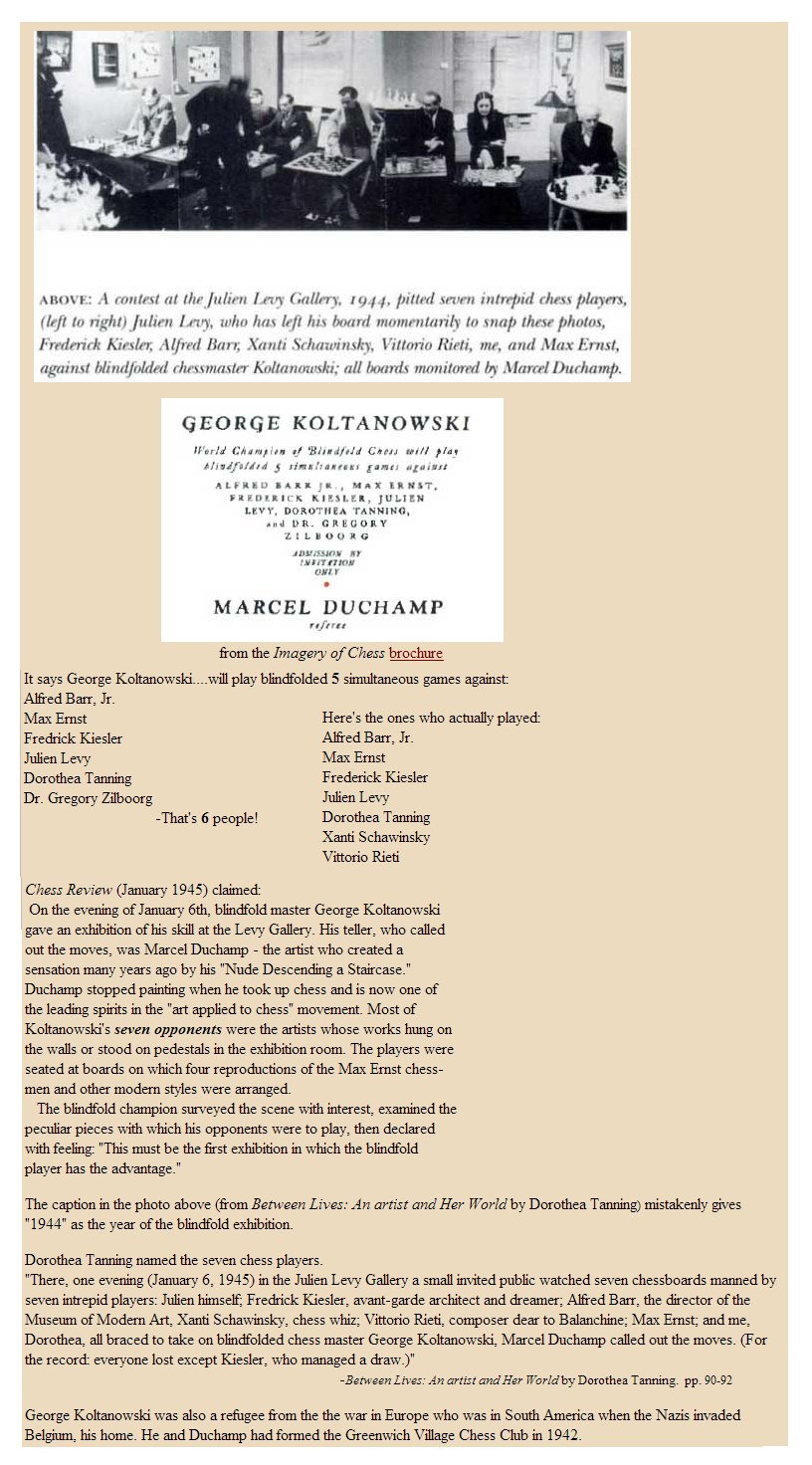

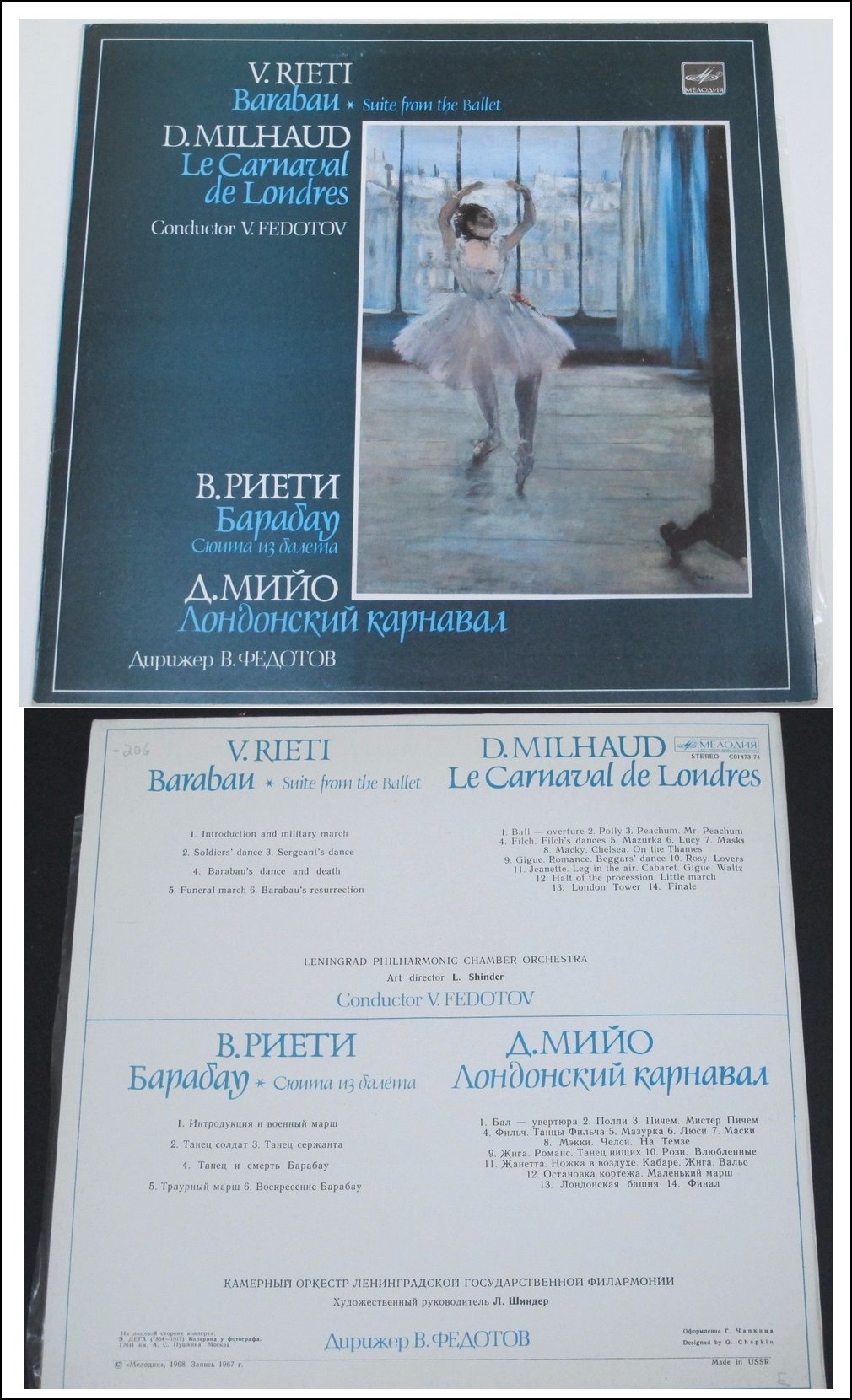

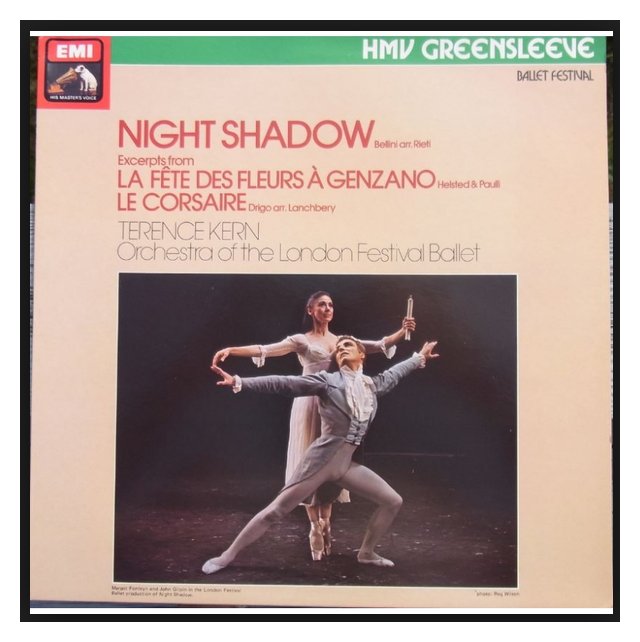

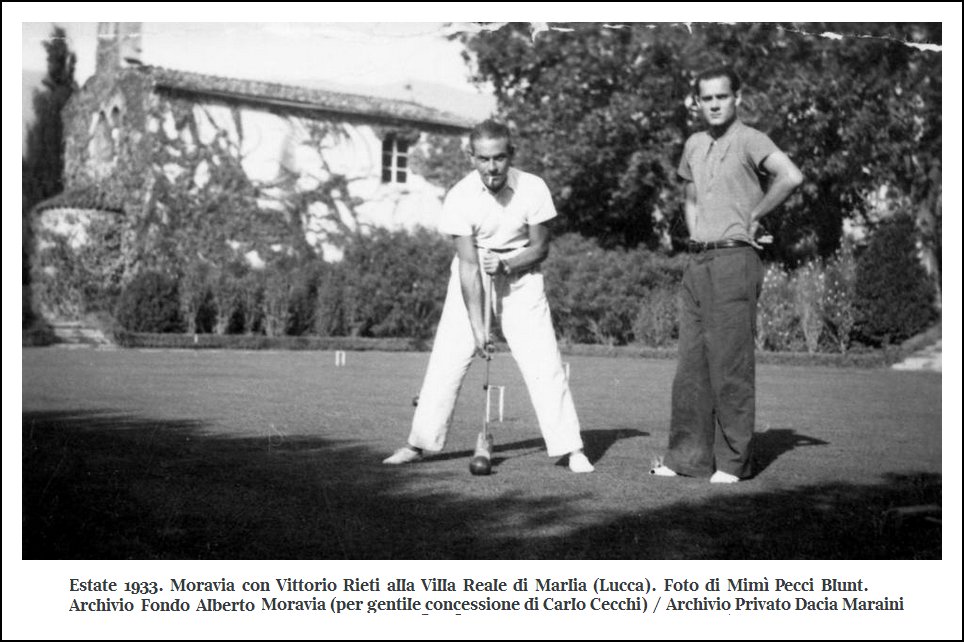

Mr. Rieti was born in Egypt, to Italian-born parents, and educated in Italy. But his music -- in its wit, craft, lack of pretense and economy of means -- shares similarities with the work of the French group of composers who called themselves Les Six, particularly that of Poulenc. The music of Stravinsky, a close friend, was also an important influence. Mr. Rieti continued to compose until shortly before his death. He used to say, "Composing every day is what keeps me alive." In his 75th, 80th and 85th birthday years, there were commemorative concerts in New York that included many new works. "Vittorio Rieti is becoming something of a wonder," Allen Hughes wrote in The New York Times after a 1985 concert. "He will be 87 years old on the 28th of this month, but he is still composing music that is as sprightly and cheerful as anything he ever wrote." [That review is reproduced at an appropriate place later on this webpage.] Other commentators remarked upon the jaunty cheer in Mr. Rieti's music, yet some professed to find its obverse as well. "Rieti's oeuvre stands apart in its specific clarity, gaiety and sophistication of a kind only he possesses," the composer Alfredo Casella once said, "yet it hides a good deal of melancholia." In 1973, Mr. Rieti said: "I go on writing music. I started when I was 12, and it has become a habit. I maintain the same esthetic assumptions I have always had. I have kept evolving in the sense that one keeps on perfecting the same ground." Mr. Rieti was born in Alexandria, Egypt, on Jan. 28, 1898. As a musician, he was largely self-taught, although he acknowledged a debt to the composer Alfredo Casella, to the piano pedagogue Giuseppe Frugatta and to some "finishing touches" from Ottorino Respighi. In the early 1920's, he belonged to a group that called itself I Tre, an Italian imitation of Les Six. His first international success came in 1924, when Casella conducted his "Concerto for Winds and Orchestra" in Prague. From 1925 to 1940, he lived in Paris, where he formed close ties with Les Six and with Stravinsky. He wrote ballet music for Diaghilev -- "Barabau" (1925) was particularly successful -- and incidental music for Louis Jouvet. In 1940, Mr. Rieti, his Italian wife, Elsie, and their son moved to the United States, where Mr. Rieti established a close working relationship with Balanchine, whose ballets "Waltz Academy" and "Native Dancers" are set to Mr. Rieti's music. However, Mr. Rieti's best-known collaboration with Balanchine remains "La Sonnambula," in which he orchestrated melodies by Bellini. The compositions of the last 20 years of Mr. Rieti's life were mostly works for string ensembles, mostly string quartets.

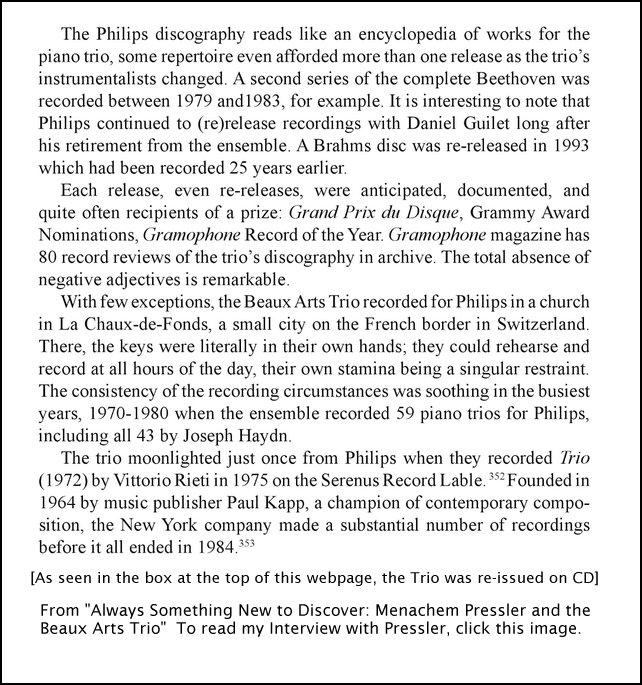

"He was like Verdi and Tintoretto in the sense that some of his most beautiful works were composed near the end of his life," said Robert Fizdale, a duopianist who, with Arthur Gold, played and recorded much of Mr. Rieti's work. Mr. Rieti wrote numerous compositions for them over the years. Mr. Gold died two years ago. While Mr. Rieti was in his 90's, a well-attended annual concert of his chamber music was given in New York, most recently at Merkin Concert Hall, by members of the Orchestra of St. Luke's. Much of the work that was performed was new, and all of it, Mr. Rieti's admirers said, sounded fresh. His son said yesterday that Mr. Rieti's final compositions, done in the last two months, were for a string quartet, and another chamber work titled "The Glorious Ensemble." Mr. Rieti taught at the Peabody Conservatory from 1948 to 1949, at the Chicago Musical College from 1950 to 1953, at Queens College from 1955 to 1960, and at the New York College of Music from 1960 to 1964. He was often encouraged to write his memoirs but said he wasn't interested. "I haven't got records, and I have a bad memory," he told an interviewer in 1973. "Too bad. I've known so many people, but I've lost track." Mr. Rieti was married in 1924 to Elsie Rappaport, who died in 1969. He is survived by his son, a painter in Paris; two grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

|

BD: You started

out studying both music and economics?

BD: You started

out studying both music and economics?

BD:

That’s too bad. I’m sorry that you had a failure with it. Then

you produced an opera for the radio called Viaggio d’Europa (1954).

BD:

That’s too bad. I’m sorry that you had a failure with it. Then

you produced an opera for the radio called Viaggio d’Europa (1954).

BD: You don’t have to worry at all about what they are

doing?

BD: You don’t have to worry at all about what they are

doing?

| MUSIC:

VITTORIO RIETI

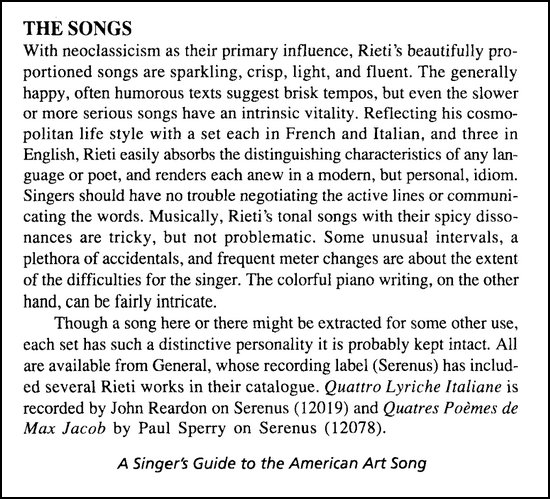

By Allen Hughes Published in The New York Times, January 13, 1985 Vittorio Rieti is becoming something of a wonder. He will be 87 years old on the 28th of this month, but he is still composing music that is as sprightly and cheerful as anything he ever wrote. Or at least he was doing so as recently as 1984. At Goodman House on Tuesday night, St. Luke's Chamber Ensemble gave a concert of his works - five all told - and all but one of them dated from the past two years. There were the ''Sonata a Dieci'' and ''Verdiana'' of 1983, ''Tre Improvisi'' and ''Concertino pro San Luca'' of 1984 and one early work, ''Madrigale,'' from 1927. All the pieces had a common denominator in that they were scored for woodwinds, trumpet, piano and string quartet. The ''Madrigale'' and one of the ''Improvisi'' also also called for a French horn. Mr. Rieti, who has lived in this country since 1940, is Italian by parentage and training, but his music is fundamentally French, influenced by Stravinsky's neo-classicism. Stravinsky was a friend, and Mr. Rieti spent a lot of time in Paris when he was young. The influence of Paris in the 20's that has stuck with him more resolutely, perhaps, than with any French composer was that music should not pretend to profundity. Grandiose statements are definitely not for him, nor is sentimentality. Instead, he is known chiefly for lighthearted music that is meant to divert, to entertain. In fact, the works in this program qualified as 20th-century equivalents of the serenades and divertimentos of 18th-century composers. Lively tunes were manipulated deftly, the instrumental coloring was bright, the textures were clear and the structural organization simple. This was generally true even of ''Verdiana,'' in which Mr. Rieti made a ballet score based on themes from Verdi operas. The performances projected the Rieti spirit admirably, St. Luke's young instrumentalists delivering the music with insouciance and charm. |

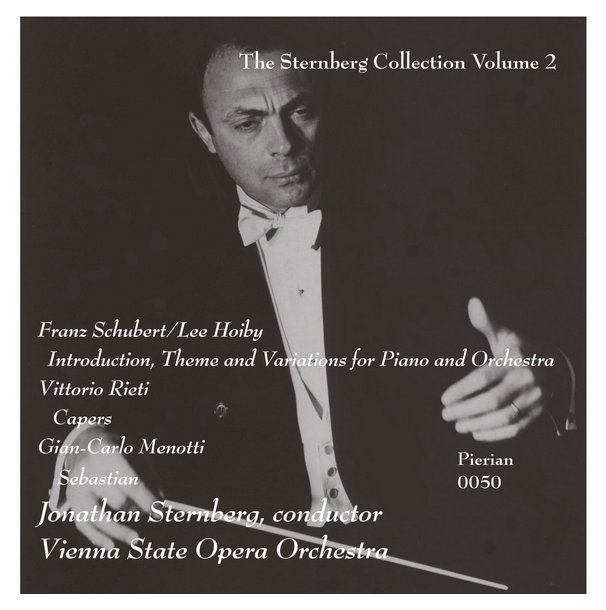

Jonathan Sternberg (Conductor)

Born: July 27, 1919 - New York, USA The American conductor, Jonathan Sternberg, is regarded by many as one of the most distinguished conductors appearing on the international podium. His performances have been unanimously acclaimed by critics, musicians and public alike from Berlin to Buenos Aires. Sternberg was born in New York of Austro-Russian parents. As a child he studied violin at the Institute of Musical Art (now the Juilliard School) in New York from 1929 to 1931. He continued his musical and academic education at the Manhattan School of Music, New York University, receiving B.A. in 1939 with viola and musicology as principal subjects. He followed that by studies in musicology at NYU Graduate School and Harvard from 1939 to 1940. During his undergraduate years, he was active as a New York critic for the Musical Leader of Chicago; he also attended rehearsals of the National Orchestral Association conducted by Leon Barzin, from whom he acquired his conducting technique. Apart from two later private sessions with Barzin (1946) and two summers (1946-1947) of conducting lessons with Pierre Monteux, he was self-taught. Sternberg began his professional career on Pearl Harbor Day, December 7, 1941, conducting the National Youth Administration Orchestra of New York in Copland's An Outdoor Overture, before entering military service. At the end of the war he found himself in Shanghai where he took over the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra for a season. After returning briefly to the USA, he moved to Vienna, making his conducting debut with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra in 1947. Then he toured extensively as a guest conductor in Europe, North America, and the Far East. He worked closely with the Haydn scholar H.C. Robbins Landon, scouring the libraries, monasteries and churches of Austria for lost manuscripts, until Robbins Landon set up the Haydn Society, for which Sternberg made a series of pioneering recordings, initially of Haydn and Mozart, not least the Nelson Mass, Posthorn Serenade and some dozen Haydn symphonies. Other recording premières under Sternberg included Schubert's Second Symphony, Rossini's Stabat mater, Prokofiev's Fifth Piano Concerto with Alfred Brendel (his first recording), Milhaud's Fantaisie Pastorale and Charles Ives's Set of Pieces. Sternberg also began to present modern American music to European audiences that had heard little of such repertory. With the RIAS orchestra in Berlin he conducted the first European performances of a large number of American scores, including Leonard Bernstein's Serenade, Menotti's Violin Concerto and the Second Symphony of Charles Ives. With other orchestras, Sternberg conducted the first European performances of works by Barber, Copland, David Diamond and Benjamin Lees. He was also responsible for a number of world premières, including Ned Rorem's First Symphony (1951) and Lászlo Lajtha's Sixth (1961). After a year at the helm of the Halifax Symphony Orchestra (1957–1958), Jonathan Sternberg was Music Director and the Principal Conductor of the Royal Flemish Opera in Antwerp, Belgium for five years (1961-1966). In 1966 he returned to the USA to accept an appointment as the Musical Director and Principal Conductor of the Harkeness Ballet of New York (1966-1968). Concurrently he was Musical Consultant to the Rebekah Harkness Foundation for their Ballet Commissioning program. Some years later he was appointed musical director and conductor of the Atlanta Municipal Theater in charge of opera and ballet performances at the new Memorial Cultural Center (1968-1969), opening the new Atlanta Memorial Arts Center with the American stage première of Purcell's King Arthur. He has also been associated with Col. De Basil's Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Outstanding among his guest engagements have been the first European tour of the Mozarteum Orchestra of Salzburg, several all-Beethoven concerts with the London Philharmonic Orchestra in the Royal Festival Hall, appearances with L'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande in Geneva, the Orchestre Lamoureux in Paris, the orchestras of Warsaw, Prague, Berlin, Munich, Stuttgart, Basel, Brussels, Monte Carlo, etc. After Atlanta, Sternberg divided his professional time with the academic world. He took up a visiting professorship of conducting at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York (1969-1971). On leaving, he took up a similar position at Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, where he taught and conducted from 1971-1989. Here, too, he conducted a number of world premières, including Music for Chamber Orchestra by David Diamond (1976), A Lincoln Address (1972) and Night Dances (1970) by Vincent Persichetti, and Stanislaw Skrowaczewski's Ricercari notturni for three saxophones and orchestra (1978). From 1989 he has been a lecturer at Chestnut Hill College. In addition he has continued pursuing his career as guest conductor on five continents. In his 80s he was still active on the podium and as a lecturer. From 2004 to 2008 he was Musical and Artistic Director of the Bach Festival of Philadelphia, sister Festival in the USA to Bachfest Leipzig. A long list of recordings made in Vienna, Salzburg, Paris and Zürich has made the name Jonathan Sternberg a familiar name to discophiles internationally. Among the artists with whom he has collaborated in concert and opera, are Isaac Stern, Yehudi Menuhin, Henryk Szeryng, Paul Badura-Skoda, Annie Fischer, Philippe Entremont, Byron Janis, Teresa Stich-Randall, Lisa Della Casa, Hilde Gueden, George London and Paul Schoeffler. In January 2009 Jonathan Sternberg received The Conductors Guild's Award for Lifetime Service in recognition of long-standing service to the art and profession of conducting. |

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on November 10, 1985. Portions were broadcast on WNIB two months later, and again in 1988 and 1993. Though no interview was included, I included some of his music on the in-flight entertainment package of Delta Airlines in January of 1989. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.