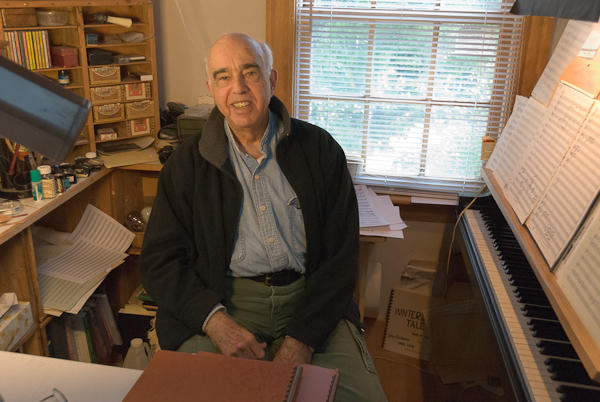

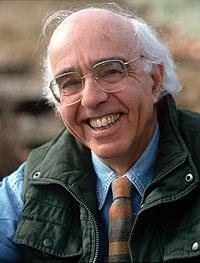

| Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Yehudi

Wyner has created a diverse body of over 60 works for orchestra, chamber

ensemble, solo performers, theater music, and liturgical services. In addition

to composing and teaching, his active and eclectic musical career includes

work as a performer, director of two opera companies, and conductor of numerous

ensembles in a wide range of repertory. "A comprehensive musician, Mr. Wyner

is an elegant pianist, a fine conductor, a prolific composer, and a revered

teacher. His works show a deep understanding of what sounds good and is technically

efficient." (Anthony Tommasini, The New

York Times, 2009). His wife, Susan Davenny Wyner, has been an enormous

source of inspiration; a number of Wyner’s most strikingly beautiful compositions

were created specifically for her. |

Bruce Duffie: Is it important for you, as a working musician,

to be able not only to play keyboard, but to sing?

Bruce Duffie: Is it important for you, as a working musician,

to be able not only to play keyboard, but to sing? BD: Did she make it fun?

BD: Did she make it fun? YW: I don't think so at all, but it depends on which pieces.

That's my opinion. That also may be a trivial, juvenile opinion.

We're talking about opinions and self-evaluation, the evaluation of peers,

not to speak of the evaluation of history. Trying to predict what it's

going to be like in many years is not a very good pursuit, it seems to me.

We're also talking about criticism of people who are in fields other than

your particular specialty, shall I daresay even people on the street and

people from other cultures. The evaluations are fast and furious and

all over the place. I'll give you an example of how difficult it is

to really determine anything absolutely. In 1989 I wrote a set of choruses

for women's chorus. My wife, Susan Davenny Wyner, was directing a women's

chorus at Cornell, where she was head of vocal studies. It was a year

honoring women's cultural achievements, and she asked if I would write a

cycle or a group of songs to women's poetry. I found some marvelous

poems by Marianne Moore [(1887-1972), American Modernist poet and writer noted

for her irony and wit]. The principal one was "O To Be a Dragon."

That sounds like a very silly little poem, and the second turned out to be

about a jellyfish. The third is "To a Chameleon," and the fourth was

a poem which had a very whimsical title, "To Victor Hugo of My Crow Pluto."

It's a mouthful, but it's a rather delightful one. She made up a whole

mythical creature — I think it's mythical, although

in one book Moore writes about this creature as if it were real and who learned

to be her friend.

YW: I don't think so at all, but it depends on which pieces.

That's my opinion. That also may be a trivial, juvenile opinion.

We're talking about opinions and self-evaluation, the evaluation of peers,

not to speak of the evaluation of history. Trying to predict what it's

going to be like in many years is not a very good pursuit, it seems to me.

We're also talking about criticism of people who are in fields other than

your particular specialty, shall I daresay even people on the street and

people from other cultures. The evaluations are fast and furious and

all over the place. I'll give you an example of how difficult it is

to really determine anything absolutely. In 1989 I wrote a set of choruses

for women's chorus. My wife, Susan Davenny Wyner, was directing a women's

chorus at Cornell, where she was head of vocal studies. It was a year

honoring women's cultural achievements, and she asked if I would write a

cycle or a group of songs to women's poetry. I found some marvelous

poems by Marianne Moore [(1887-1972), American Modernist poet and writer noted

for her irony and wit]. The principal one was "O To Be a Dragon."

That sounds like a very silly little poem, and the second turned out to be

about a jellyfish. The third is "To a Chameleon," and the fourth was

a poem which had a very whimsical title, "To Victor Hugo of My Crow Pluto."

It's a mouthful, but it's a rather delightful one. She made up a whole

mythical creature — I think it's mythical, although

in one book Moore writes about this creature as if it were real and who learned

to be her friend. BD: And yet when your team scores a touchdown, then the four

or five of you around the set are all screaming and hollering!

BD: And yet when your team scores a touchdown, then the four

or five of you around the set are all screaming and hollering! BD: I was going to ask if it also had some Wyner in it.

BD: I was going to ask if it also had some Wyner in it. YW: Right, get on with it! I've learned to get on with

it, but certainly to really craft pieces so that they stand up. They

stand up through many performances, and they stand up through that inevitable

process that every performer has to go through. You have got to get

the notes down. If the notes aren't right, if the local event isn't

right, if it doesn't make sense, if it doesn't give both physical and aural

satisfaction, why is the performer going to keep at it? Since I'm a

performer, I'm very sympathetic to that. I've had some time to do assignments,

to play pieces which were badly made — I mean badly

made! — where the notes were indifferently chosen,

where the physical effort to achieve some semblance of the notation at the

tempo given was immense, or the skips or the fast moves were ridiculous;

the sonorities were ugly or they were not really resonating or they obliterated

another part. There are any number of possible viruses that can enter

the body politic of music, and I resented every minute having to do that

kind of dog work when there was no payoff. I wasn't willing to wait

the five months until the piece would be in its final form, where I could

go out and give a smash-bang performance of it one time, and in order to

do that I would have had to sacrifice my life to this moment-to-moment thing.

We find in working on the great music of the past, that every moment has

an excitement. Bach, for example, from that point of view is the be-all

and end-all. You can play anything of Bach and you will get the message.

YW: Right, get on with it! I've learned to get on with

it, but certainly to really craft pieces so that they stand up. They

stand up through many performances, and they stand up through that inevitable

process that every performer has to go through. You have got to get

the notes down. If the notes aren't right, if the local event isn't

right, if it doesn't make sense, if it doesn't give both physical and aural

satisfaction, why is the performer going to keep at it? Since I'm a

performer, I'm very sympathetic to that. I've had some time to do assignments,

to play pieces which were badly made — I mean badly

made! — where the notes were indifferently chosen,

where the physical effort to achieve some semblance of the notation at the

tempo given was immense, or the skips or the fast moves were ridiculous;

the sonorities were ugly or they were not really resonating or they obliterated

another part. There are any number of possible viruses that can enter

the body politic of music, and I resented every minute having to do that

kind of dog work when there was no payoff. I wasn't willing to wait

the five months until the piece would be in its final form, where I could

go out and give a smash-bang performance of it one time, and in order to

do that I would have had to sacrifice my life to this moment-to-moment thing.

We find in working on the great music of the past, that every moment has

an excitement. Bach, for example, from that point of view is the be-all

and end-all. You can play anything of Bach and you will get the message. YW: [Thinks for a long while] I find that a difficult

question to answer partially because I think there is a very confidential

relationship that exists between a teacher and his students. For that

reason, I see my composition students one-on-one. I have colleagues

who somehow manage to see the whole group and share that with the whole class.

In my own experience I didn't like it; I didn't enjoy that. I really

wanted the absolute individual undivided attention of my teacher, and when

I didn't get it I was rather bored. That was my own problem; I was

unable to enter the worlds of some of my colleagues, or some of my peers.

But if you think about it, if I just said baldly, "Yes, I'm very pleased

with the work that comes out of my students," there'd be a certain amount

of self-aggrandizement in that. I would be taking credit for what's

coming out. If I said, "No, I just think they're a bunch of slobs and

slouches and they don't really match up," that would not be such a good thing

even if they didn't hear about it. [In comically exaggerated deep tone of

voice, imitating a busybody] "I heard your teacher said that he doesn't like

the work of his students!" Then the student confronts me and I start

to blubber! Then there are the students who write music that frankly

I don't understand! Am I going to admit that to them? Well, I

do, and I try to help them in other ways. There are manners of encouragement

where you don't really understand exactly what's up. You don't always

meet with a sympathetic reception. Milhaud is reported to have said

in an interview, "Boulez

loathes my music. He detests my music, but he performs it better than

anybody in the world." So I think I can help my students even when

I don't understand what they're doing, which happens; even when I don't approve

of what's coming off the page, which happens; and even when I think what

they're doing is wonderful. That happens also. They do all happen,

and sometimes they don't happen in my presence. It may not happen while

I'm with them. It may happen later on, and the appreciation might come.

Or some of the seeds that are planted may germinate and bear some fruit.

But one never knows. You know so little about your children and their

lives; you know so little about your students and their lives.

YW: [Thinks for a long while] I find that a difficult

question to answer partially because I think there is a very confidential

relationship that exists between a teacher and his students. For that

reason, I see my composition students one-on-one. I have colleagues

who somehow manage to see the whole group and share that with the whole class.

In my own experience I didn't like it; I didn't enjoy that. I really

wanted the absolute individual undivided attention of my teacher, and when

I didn't get it I was rather bored. That was my own problem; I was

unable to enter the worlds of some of my colleagues, or some of my peers.

But if you think about it, if I just said baldly, "Yes, I'm very pleased

with the work that comes out of my students," there'd be a certain amount

of self-aggrandizement in that. I would be taking credit for what's

coming out. If I said, "No, I just think they're a bunch of slobs and

slouches and they don't really match up," that would not be such a good thing

even if they didn't hear about it. [In comically exaggerated deep tone of

voice, imitating a busybody] "I heard your teacher said that he doesn't like

the work of his students!" Then the student confronts me and I start

to blubber! Then there are the students who write music that frankly

I don't understand! Am I going to admit that to them? Well, I

do, and I try to help them in other ways. There are manners of encouragement

where you don't really understand exactly what's up. You don't always

meet with a sympathetic reception. Milhaud is reported to have said

in an interview, "Boulez

loathes my music. He detests my music, but he performs it better than

anybody in the world." So I think I can help my students even when

I don't understand what they're doing, which happens; even when I don't approve

of what's coming off the page, which happens; and even when I think what

they're doing is wonderful. That happens also. They do all happen,

and sometimes they don't happen in my presence. It may not happen while

I'm with them. It may happen later on, and the appreciation might come.

Or some of the seeds that are planted may germinate and bear some fruit.

But one never knows. You know so little about your children and their

lives; you know so little about your students and their lives.

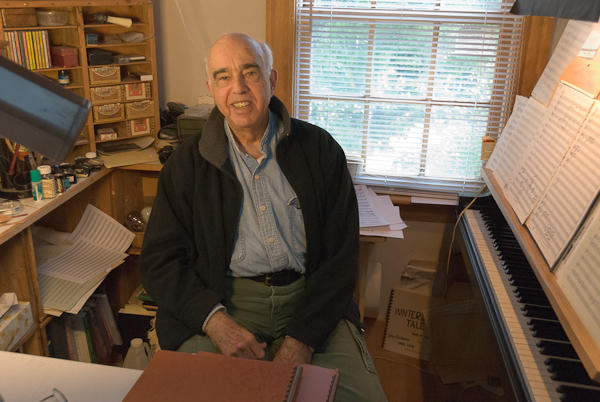

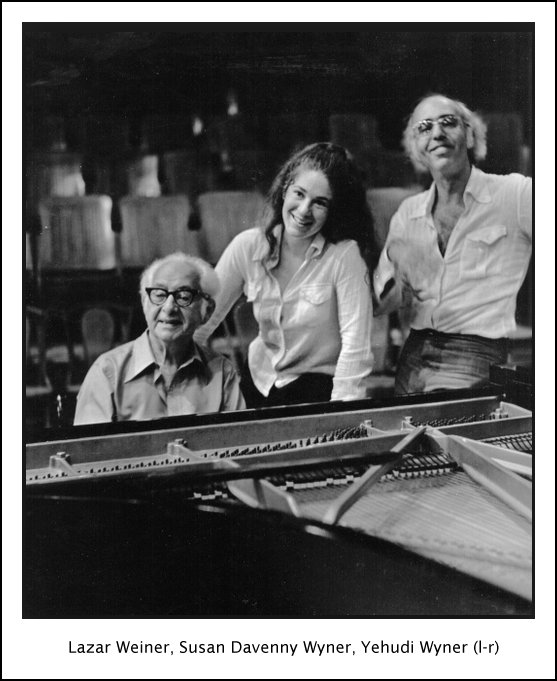

Wyner was born in Western Canada and

grew up in New York City in a musical family. His father, Lazar Weiner, was

the preeminent composer of Yiddish Art Song as well as a notable creator

of liturgical music for the modern synagogue. This early exposure paved the

way for a Diploma in piano from The Juilliard School and further musical

studies at Yale and Harvard Universities with composers Richard Donovan,

Walter Piston, and Paul Hindemith. A Handel course at Harvard brought Wyner

to the attention of Randall Thompson, who became a staunch supporter and friend.

In 1953, Wyner won the Rome Prize in Composition enabling him to spend the

next three years at the American Academy in Rome, composing, performing,

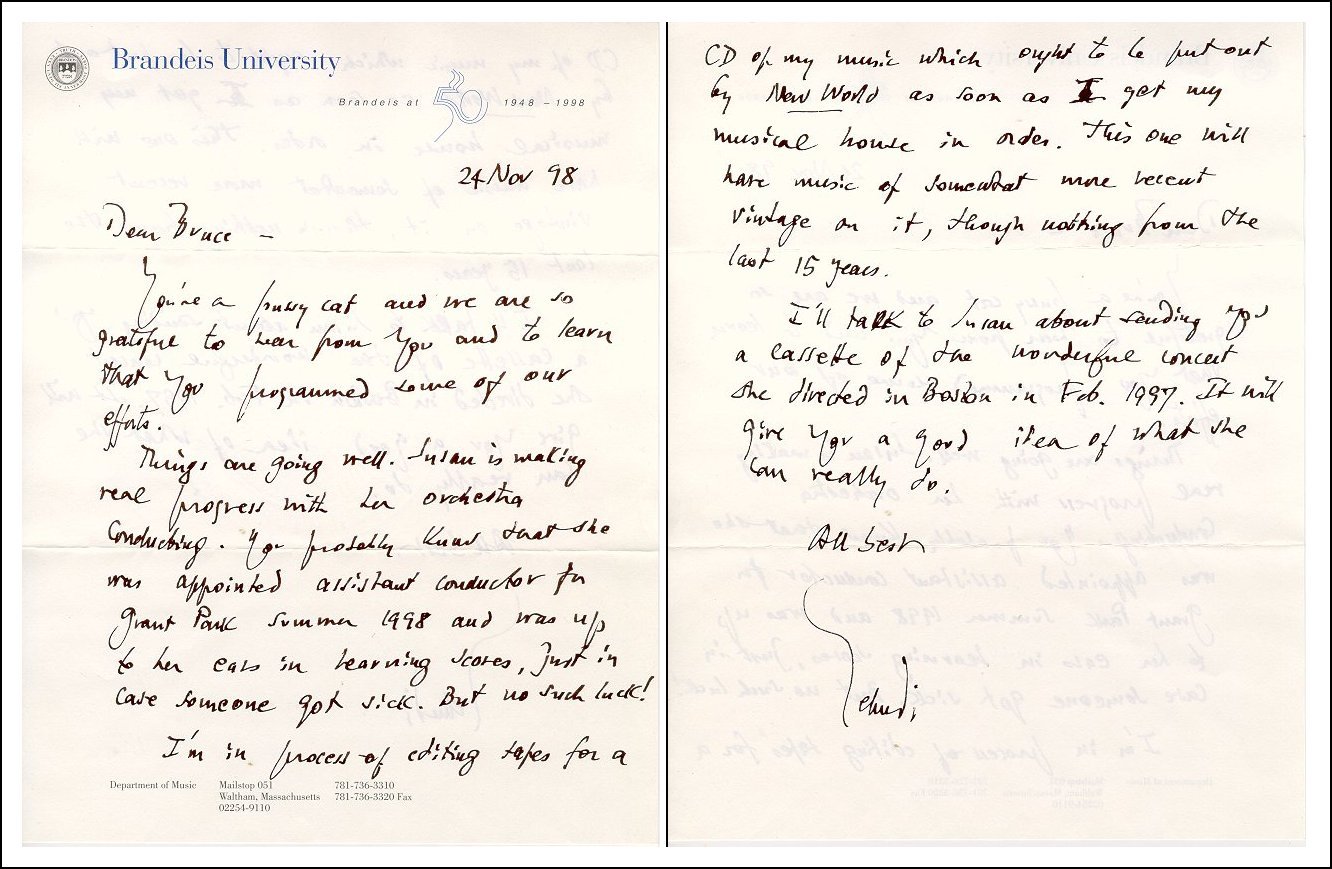

and traveling. Since then, he has received many honors including the 2006

Pulitzer Prize in Music for his Piano concerto "Chiavi in mano," two

Guggenheim Fellowships, a grant from the American Institute of Arts and Letters,

and the Brandeis Creative Arts Award. In 1998, Wyner received the Elise Stoeger

Award from Lincoln Center's Chamber Music Society for his lifetime contribution

to chamber music. His Horntrio was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize

in 1998, and in 1999 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts

and Letters.

Wyner was born in Western Canada and

grew up in New York City in a musical family. His father, Lazar Weiner, was

the preeminent composer of Yiddish Art Song as well as a notable creator

of liturgical music for the modern synagogue. This early exposure paved the

way for a Diploma in piano from The Juilliard School and further musical

studies at Yale and Harvard Universities with composers Richard Donovan,

Walter Piston, and Paul Hindemith. A Handel course at Harvard brought Wyner

to the attention of Randall Thompson, who became a staunch supporter and friend.

In 1953, Wyner won the Rome Prize in Composition enabling him to spend the

next three years at the American Academy in Rome, composing, performing,

and traveling. Since then, he has received many honors including the 2006

Pulitzer Prize in Music for his Piano concerto "Chiavi in mano," two

Guggenheim Fellowships, a grant from the American Institute of Arts and Letters,

and the Brandeis Creative Arts Award. In 1998, Wyner received the Elise Stoeger

Award from Lincoln Center's Chamber Music Society for his lifetime contribution

to chamber music. His Horntrio was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize

in 1998, and in 1999 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts

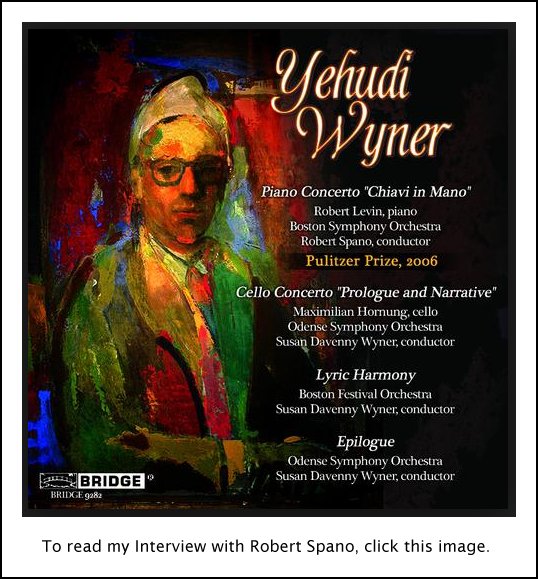

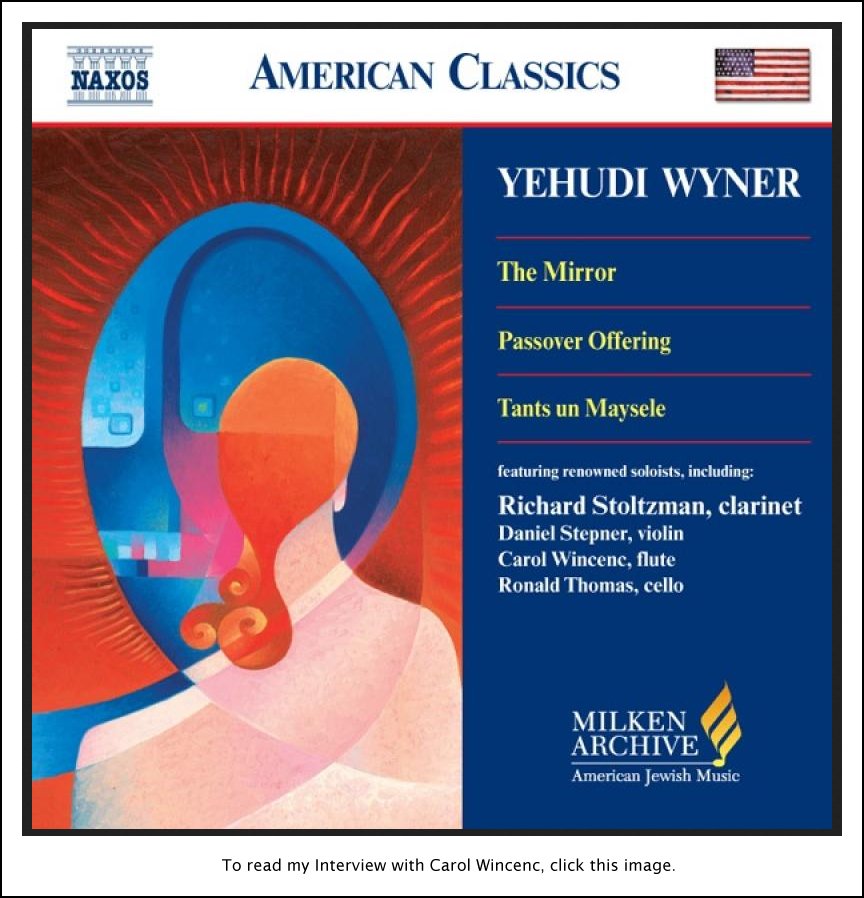

and Letters.Among Wyner's most important works is the liturgical piece Friday Evening Service for cantor and chorus, and it is this piece that initiated his relationship with Associated Music Publishers. The composer elaborates, "The circumstances of my initial contact with Schirmer/AMP [came about] in the spring of 1963, [when] the premiere of my new Friday Evening Service took place at the Park Avenue Synagogue in New York. The next day, I received a call from a person, then unknown to me, named Hans Heinsheimer [former G. Schirmer Director of Publications]. After identifying himself, he said that Samuel Barber had attended the premiere and urged Heinsheimer to be in touch with me to discuss a possible publishing relationship. Of course I was astonished!" Wyner has been commissioned by the Ford Foundation, the Koussevitzky Foundation at the Library of Congress, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival, Bravo! Vail Valley Music Festival, Michigan and Yale Universities, and many chamber music ensembles including Aeolian, DaCapo, Parnassus, Collage, No Dogs Allowed, the Boston Symphony Chamber Players, and 20th Century Unlimited. Recordings of his music can be found on New World Records, Naxos, Bridge, Albany Records, Pro Arte, CRI, 4Tay Records, and Columbia Records. Since 1968, Wyner has been a keyboard artist for the Bach Aria Group. In this capacity he has performed and conducted a substantial number of the Bach cantatas, concertos, and motets. He recently retired as the Walter W. Naumburg Professor of Composition at Brandeis University, a post he held since 1991. He also taught at Yale University as head of the Composition faculty, at SUNY Purchase as Dean of the Music Division, as a visiting professor at Cornell and Harvard Universities, and as a member of the chamber music faculty at the Tanglewood Music Center from 1975 to 1997. He has been composer-in-residence at the Sante Fe Chamber Music Festival (1982), the American Academy in Rome (1991), and the Rockefeller Center at Bellagio, Italy (1998). His notable orchestral works include: Prologue and Narrative for Cello and Orchestra (1994), commissioned by the BBC Philharmonic for the Manchester International Cello Festival; Lyric Harmony for orchestra (1995), commissioned by Carnegie Hall for the American Composers Orchestra; and Epilogue for orchestra (1996), commissioned by the Yale School of Music. Notable works for smaller ensembles include: String Quartet (1985); Toward the Center for piano (1988); Sweet Consort for flute and piano (1988); 0 To Be a Dragon choruses for women's voices (1989); Trapunto Junction for horn, trumpet, trombone, and percussion (1991), commissioned by the Boston Symphony Chamber Players; Praise Ye the Lord for soprano and ensemble (1996), commissioned by Dawn Upshaw and the 92nd Street Y; Horntrio (1997), commissioned by Worldwide Concurrent Premieres Inc. for 40 ensembles; Madrigal for String Quartet (1999), commissioned by the Lydian String Quartet at Brandeis; The Second Madrigal: Voices of Women (1999), commissioned by the Koussevitzky Foundation at the Library of Congress; Tuscan Triptych: Echoes of Hannibal for string orchestra (2002); Commedia for clarinet and piano (2002), commissioned by Emanuel Ax and Richard Stoltzman; and Trio 2009 for clarinet, cello, and piano (2009), commissioned by the Chamber Music San Francisco. His music is published by Associated Music Publishers, Inc. — November 2011

Composers Charles Wuorinen, Milton Babbit, Yehudi Wyner and Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, with Del Bryant of BMI (l-r) [Photo by Gary Gershoff]

Yehudi Wyner, John Harbison, Robert Levin, and Bernard Rands (l-r)

|

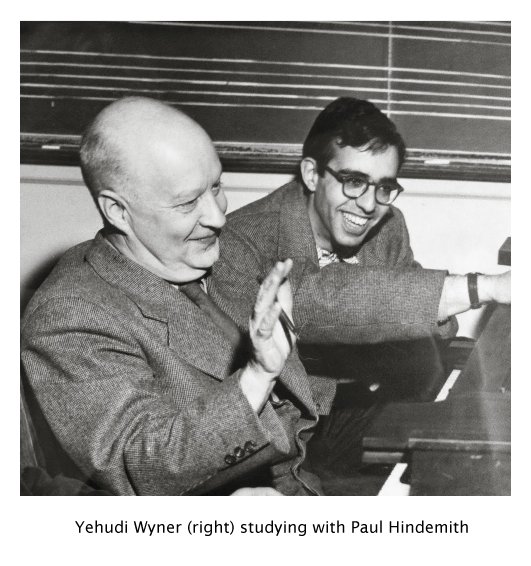

This interview was recorded in Chicago on December 19, 1994.

Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB two months later, and

again in 1999. It was also used on WNUR in 2009 and 2010, and on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio in 2009. An audio copy was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. This transcription

was made and posted on this website late in 2011.

To see a ful list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.