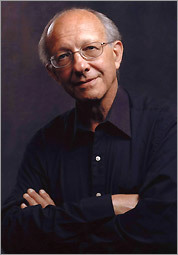

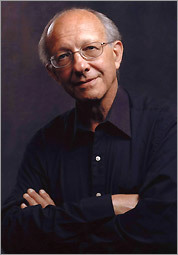

| As head of the performance

faculty, Gilbert Kalish had done much to create the uniquely supportive and

stimulating environment of Stony Brook's music department. Through his activites

as performer and educator, he has become a major figure in American music

making. A native New Yorker, Mr. Kalish studied with Leonard Shure, Julius

Hereford and Isabelle Vengerova. He is a frequent guest artist with many

of the world's most distinguished chamber ensembles. He was a founding member

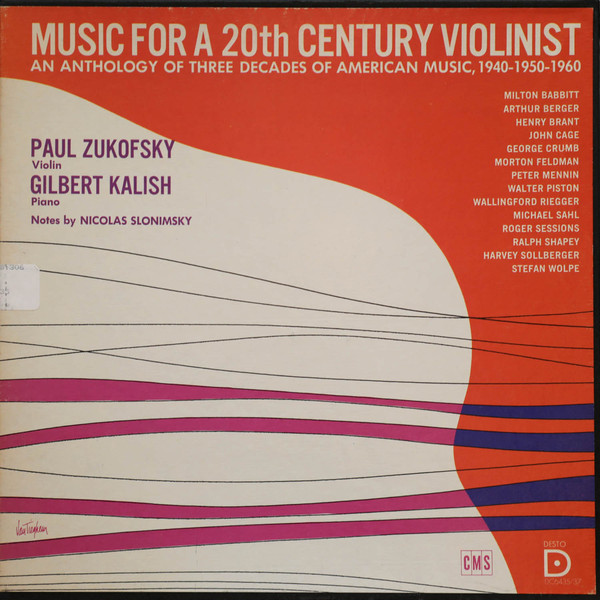

of the Contemporary Chamber Ensemble, a pioneering new music group that flourished

during the 1960's and '70's. He is noted for his partnerships with other

artists, including cellists Timothy Eddy and Joel Krosnick, soprano Dawn Upshaw, and, perhaps

most memorably, his thirty-year collaboration with mezzo-soprano Jan DeGaetani.

In addition to teaching at Stony Brook, he has also served on the faculties

of the Tanglewood Music Center, the Banff Centre and the Steans Institute

at Ravinia. Mr. Kalish's discography of some 100 recordings encompasses classical

repertory, 20th-century masterworks and new compositions. In 1995 the University

of Chicago presented him with the Paul Fromm Award for distinguished

service to the music of our time. -- Links on this page refer to my interviews

elsewhere on my website. BD

|

BD: You have your own sound?

BD: You have your own sound? GK: That’s part of the challenge, and in a way,

part of the fun of being a pianist. The given is you do not have your

own instrument, and wherever you come, you deal with the instrument that you’re

given. The challenge is to make it something that sounds sort of like

you, like what you believe you want to sound like, and that takes the best

quality out of that piano and uses it.

GK: That’s part of the challenge, and in a way,

part of the fun of being a pianist. The given is you do not have your

own instrument, and wherever you come, you deal with the instrument that you’re

given. The challenge is to make it something that sounds sort of like

you, like what you believe you want to sound like, and that takes the best

quality out of that piano and uses it. GK: One has the right to expect that of a fine

modern instrument. But don’t forget, in all of these cases you’re playing

basically on an instrument very different from the one for which the piece

was written. That’s also part of the fun; one talks about a sense of

style. What is a sense of style? Well, it’s many, many things.

One of the things is the milieu in which that piece was written. What

was the instrument Mozart had? Any great composer writes for what

they have, and it’s okay that we’re playing on a very different instrument.

But it’s really important, in a way, to think about the qualities of an early

fortepiano, and how can we, in some way, transfer those qualities to our own

piano. So I think I am obligated to play very differently in Mozart

and in Brahms. And I try to. It’s not even a matter of try to.

I have a sound in my head and I want to make that sound. So I try to

find a way, on that piano, to make the sound, to articulate in a certain way.

For instance, pedal. For instance, legato. For instance, dynamic

range. It’s not the same in Mozart and in Brahms.

GK: One has the right to expect that of a fine

modern instrument. But don’t forget, in all of these cases you’re playing

basically on an instrument very different from the one for which the piece

was written. That’s also part of the fun; one talks about a sense of

style. What is a sense of style? Well, it’s many, many things.

One of the things is the milieu in which that piece was written. What

was the instrument Mozart had? Any great composer writes for what

they have, and it’s okay that we’re playing on a very different instrument.

But it’s really important, in a way, to think about the qualities of an early

fortepiano, and how can we, in some way, transfer those qualities to our own

piano. So I think I am obligated to play very differently in Mozart

and in Brahms. And I try to. It’s not even a matter of try to.

I have a sound in my head and I want to make that sound. So I try to

find a way, on that piano, to make the sound, to articulate in a certain way.

For instance, pedal. For instance, legato. For instance, dynamic

range. It’s not the same in Mozart and in Brahms. BD: Then the composer also has to trust you.

BD: Then the composer also has to trust you.

GK:

I’ve lived through many decades of compositional style, more or less having

been brought up from the nineteenth century tradition, growing up and reaching

the time when I had to enter the profession in the middle-late fifties.

I’ve heard the music of all of these decades — the different

styles, the different conventions, the different music that was considered

elite and correct, and that was scorned. It’s been fascinating to see

that what was the right music, what was considered appropriate in the fifties

and sixties, fell into disfavor in the seventies and eighties, and is considered

academic and dry and uninteresting. Every composer is a product of

their time and of their own background. Ralph Shapey, for instance,

is in his late seventies. His compositional style and philosophy were

formed in the forties and the fifties. He’s writing, thank goodness,

the music that he feels deeply and believes in. Somebody who arrived

on the scene twenty years later could not possibly write that music!

Somebody who came twenty years later than Beethoven could not possibly write

the music that Beethoven wrote.

GK:

I’ve lived through many decades of compositional style, more or less having

been brought up from the nineteenth century tradition, growing up and reaching

the time when I had to enter the profession in the middle-late fifties.

I’ve heard the music of all of these decades — the different

styles, the different conventions, the different music that was considered

elite and correct, and that was scorned. It’s been fascinating to see

that what was the right music, what was considered appropriate in the fifties

and sixties, fell into disfavor in the seventies and eighties, and is considered

academic and dry and uninteresting. Every composer is a product of

their time and of their own background. Ralph Shapey, for instance,

is in his late seventies. His compositional style and philosophy were

formed in the forties and the fifties. He’s writing, thank goodness,

the music that he feels deeply and believes in. Somebody who arrived

on the scene twenty years later could not possibly write that music!

Somebody who came twenty years later than Beethoven could not possibly write

the music that Beethoven wrote. BD:

Well, are you optimistic about the future of musical composition, especially

for the piano?

BD:

Well, are you optimistic about the future of musical composition, especially

for the piano? GK: I’m very content with what I’ve done.

I’m astonished. I never expected it. I grew up alone in my musical

world. It was important for my mother that if you had a child with a

gift, that it be developed, but she didn’t really know a lot. And I

went to public schools. I went to Columbia University. I didn’t

go to Juilliard. I didn’t go to a music school. I studied privately

and somehow slipped into the profession. I didn’t do competitions.

I didn’t do any of that! I slipped into the profession sort of on the

shoulders of having learned and loved chamber music. Then I was feeling

really curious about new music. I married young and felt, “I have to

make a living,” and this was one outlet because other people were not doing

it. The people at Juilliard were not doing it because their teachers

were teaching them the old war horses and they were going for competitions.

I just was not taking that route. I somehow got in on the periphery

and did new music and chamber music. Somehow that led me to my solo

work of Ives, and then back to my roots, where I studied what I studied when

I was a youngster — the great masters. Then came

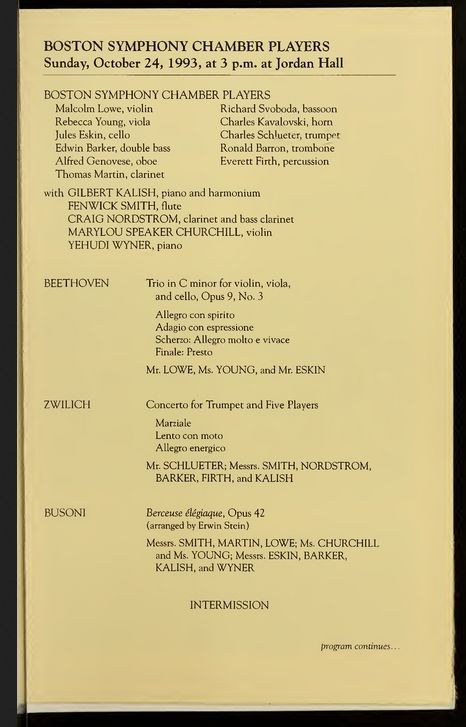

the opportunity to do Haydn and to do chamber music with the Boston Symphony

Chamber Players for thirty years, with my colleagues in the Juilliard Quartet,

with Jan DeGaetani. We met as youngsters and we were in a new music

group together, and just did recitals because we were curious young people

and we wanted to do recitals, so we did recitals. I remember I had a

series at Swarthmore College and I said to Jan, “I can’t offer you more than

seventy-five dollars, but I can tell you that I’ll rehearse as much as you

want. Let’s do a recital.” And you know, out of nothing, all

this things somehow developed.

GK: I’m very content with what I’ve done.

I’m astonished. I never expected it. I grew up alone in my musical

world. It was important for my mother that if you had a child with a

gift, that it be developed, but she didn’t really know a lot. And I

went to public schools. I went to Columbia University. I didn’t

go to Juilliard. I didn’t go to a music school. I studied privately

and somehow slipped into the profession. I didn’t do competitions.

I didn’t do any of that! I slipped into the profession sort of on the

shoulders of having learned and loved chamber music. Then I was feeling

really curious about new music. I married young and felt, “I have to

make a living,” and this was one outlet because other people were not doing

it. The people at Juilliard were not doing it because their teachers

were teaching them the old war horses and they were going for competitions.

I just was not taking that route. I somehow got in on the periphery

and did new music and chamber music. Somehow that led me to my solo

work of Ives, and then back to my roots, where I studied what I studied when

I was a youngster — the great masters. Then came

the opportunity to do Haydn and to do chamber music with the Boston Symphony

Chamber Players for thirty years, with my colleagues in the Juilliard Quartet,

with Jan DeGaetani. We met as youngsters and we were in a new music

group together, and just did recitals because we were curious young people

and we wanted to do recitals, so we did recitals. I remember I had a

series at Swarthmore College and I said to Jan, “I can’t offer you more than

seventy-five dollars, but I can tell you that I’ll rehearse as much as you

want. Let’s do a recital.” And you know, out of nothing, all

this things somehow developed.| Gilbert Kalish leads a musical

life of unusual variety and breadth. His profound influence on the musical

community as educator, and as pianist in myriad performances and recordings,

has established him as a major figure in American music making. A native New Yorker and graduate of Columbia College, Mr. Kalish studied with Leonard Shure, Julius Hereford and Isabella Vengerova. He has been the pianist of the Boston Symphony Chamber Players since 1969 and was a founding member of the Contemporary Chamber Ensemble; a group devoted to new music that flourished during the 1960's and 70's. He is a frequent guest artist with many of the world's most distinguished chamber ensembles. His thirty-year partnership with the great mezzo-soprano Jan DeGaetani was universally recognized as one of the most remarkable artistic collaborations of our time. He maintains long-standing duos with the cellists Timothy Eddy and Joel Krosnick, and he appears frequently with soprano Dawn Upshaw. As educator he is Leading Professor and Head of Performance Activities at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. From 1968-1997 he was a faculty member of the Tanglewood Music Center and served as the "Chairman of the Faculty" at Tanglewood from 1985-1997. He often serves as guest faculty at distinguished music institutions such as the Banff Centre and the Steans Institute at Ravinia, and is renowned for his master class presentations. Mr. Kalish's discography of some 100 recordings encompasses classical repertory, 20th Century masterworks and new compositions. Of special note are his solo recordings of Charles Ives' Concord Sonata and Sonatas of Joseph Haydn, an immense discography of vocal music with Jan DeGaetani and landmarks of the 20th Century by composers such as Carter, Crumb, Shapey and Schoenberg. In 1995 he was presented with the Paul Fromm Award by the University of Chicago Music Department for distinguished service to the music of our time. Curriculum Vitae Education: Columbia College, B.A. Supplementary Studies: Berkshire Music Center Marlboro Festival Teachers: Julius Hereford, Isabella Vengerova, Leonard Shure Faculty Positions: SUNY Stony Brook Artist-in-Residence/Professor 1970 - present SUNY Purchase 1975-1979 Rutgers University 1966-1969 Swarthmore College Associate in Performance 1966-1974 Honors: Honorary Doctorate - Swarthmore College, 1987 Paul Fromm Award - University of Chicago, 1995 (for distinguished service to the music of our time) Guest Teacher of the Year, Philadelphia Settlement School 1996 Grammy nomination Winner of "Indie" award 1997 and 1999 - given by Independent Record Producers for the Outstanding Chamber Music Disc of the year Ensembles: Contemporary Chamber Ensemble 1962-1979 Regular Pianist for Boston Symphony Chamber Players 1969-1998 Gramercy Chamber Ensemble Aeolian Chamber Players Penn Contemporary Players (Univ. of Pennsylvania) Guest Appearances with: Boston Symphony Orchestra Buffalo Symphony Orchestra Greenwich Symphony Newton Symphony New York Philharmonic Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Concord Quartet Emerson Quartet Fine Arts Quartet Juilliard Quartet Milwaukee Chamber Orchestra New Jersey Chamber Orchestra New World String Quartet New York Woodwind Quintet Orion String Quartet Sea Cliff Chamber Players Thouvenal String Quartet 1999-2000: Guest artist with: Ying Quartet, Minnesota Chamber Music, St. Lawrence Quartet, Talich Quartet, New England String Ensemble, Avalon Quartet, The Barge Series (NY), Houston Chamber Music Society. Radio and Television: Many appearances for BBC, Australian, New Zealand, German and Ammerican TV including first British Broadcast of Crumb Makrokosmos for Solo Piano; Complete Beethoven Violin and Piano Sonatas; Complete Ives Violin and Piano Sonatas. Solo Work: Recitals throughout much of the world. Appearances at many leading music festivals, such as Mostly Mozart, New York; Brighton and Aldeburgh, England; Ojai, California; Lucerne, Switzerland; Sarasota, Florida; Badenweiler, Germany; Rotterdam and Amsterdam, Netherlands, and many others. Numerous first performances of works written for the performer by many of the world's leading composers (Carter, Crumb, Reynolds, Kupferman, etc.) Concerto appearances in some of the most significant works of the 20th Century by composers, such as Berg, Berio, Carter, Messiaen and Stravinsky. Concerts: Numerous concert appearances (about 50 per year) in many of the major world centers including New York concerts at Carnegie, Avery Fisher, Town Hall, 92nd Street "Y", Symphony Space, Tully Hally, Weill, Merkin, Miller Theatre (including the first solo piano recital in this newly renovated Columbia University concert hall). Tours of Japan, Europe and South America with the Boston Symphony Chamber Players. European and American tours with leading concert artists, such as Jan De Gaetani, Dawn Upshaw, The Juilliard Quartet and many others. World Premiere Performances: Works by Bacon, Carter, Copland, Crumb, Ives, Kirchner, Perle, Shapey, Walden, etc. (1999-2000) David Diamond, Osvaldo Golijov, James Primosch, Ralph Shapey Recordings: Beethoven - Complete Works for Cello & Piano (Arabesque) Berg - Trio for Violin, Clarinet and Piano Berger - 3 pieces for 2 Pianos (Columbia) Berger - Cello Duo, Guitar Trio (New World) Alan Blank - Notation for Piano (CRI) Brahms Horn and Clarinet Trios (Nonesuch) Brahms Songs (Arabesque) Brahms Piano Quartet (Musical Heritage) Carter - Double Concerto, Duo for Violin and Piano (Nonesuch) Copland - Piano Variations, Piano Quartet and Sextet (Nonesuch) Crumb - Makrokosmos III for 2 Pianos and 2 Percussion (Nonesuch) Crumb - Apparition (Bridge) Debussy - Afternoon of a Faun (arranged by Schonberg) Debussy - En Blanc et Noir (Nonesuch) Debusy and Ravel Songs (Arabesque) Foote and Beach - Violin Piano Sonatas (New World) 1977 Steven Foster - Songs (Nonesuch) Haydn - Piano Sonatas, five volumes (Nonesuch) Ives - Piano Trio - Complete works for Piano and Strings (Columbia) The Complete Sonatas for Violin and Piano (Folkways) Concord Sonata - (Nonesuch) Ives - Songs (Bridge) Ives Trio (with Yo Yo Ma) (SONY) Kupferman - Celestial City (Concerto for Piano and tape) (Serenus) Concerto for Flute - Piano and String Quartet (Serenus) Martino - Trio (CRI) Mozart - Sonata and Fantasie (Baldwin) Poulenc - Music for Piano and Winds (Nonesuch) Rachmaninoff and Chausson - Songs (Nonesuch) Saint Saens - Works for various wind instruments and piano (Desto) Schoenberg - Pierrot Lunaire (Concert Disc) Suite Opus 29 (Deutshe Gramaphone) Kammerkonzert Opus 9 (arranged by Webern) Fantasie for Violin and Piano Pierrot Lunaire - 2nd recording (Nonesuch) Schoenberg-Schubert - Songs (Nonesuch) Schubert - Solo Piano Music (Nonesuch) Schuman - Vocal Duets (Nonesuch) Shapey - Cello Sonata (New World) Silver - Cello Sonata (CRI) Smetana Trio (Nonesuch) Sonatas for Violin and Piano, 2nd recording (Nonesuch) Songs - (Nonesuch) Strauss - Waltzes (arranged by Schonberg, Berg and Webern) (Recorded by DGG with the Boston Symphony Chamber Players New American Music on 5 records with the Contemporary Chamber Ensemble with works by Druckman, Harbison, Myrow, Reynolds, Schwantner, Shifrin Wolpe (Nonesuch) Wolf - Songs (Nonesuch) With Ronald Roseman, Oboe Hindemith - Sonata Schuman - Romances Kupferman - Dialogues Schuller _Sonata (Desto) Music in the Shadow of WW I (Arabesque) Indie Award - 1999 Music in the Shadow of WW II (Arabesque) Indie Award - 1997 Songs of Messiaen with Dawn Upshaw (to be released by Nonesuch) Harbison Songs & Piano Quintet with Dawn Upshaw and the Boston Symphony Chamber Players (Nonesuch) 3 time nominee for Grammy Award Selected as mong the best recording of the year by New York Times, Stero Review, Time, Newsweek, High Fidelity, Village Voice Reissue on CD of many previous LP records including Ives Concord Sonata and Haydn Piano Sonatas plus works of Brahms, Ives, Wolf, Ravel, Schumann, Schonberg, etc. Master Classes: (1999-2000) The Banff Centre Toronto Conservatory Boston Conservatory Peabody Conservatory The Eastman School Port Jefferson Arts Council (Fees donated to the SB Music Dept.) Music Conservatory, Madrid, Spain Festival Concert Appearances: Aldeburgh, England Badenweler, Germany Banff Centre, Canada Bonn, Germany Chamber Music West, San Francisco Duisburg, Germany Kennedy Center Mostly Mozart, Avery Fisher Hall, NY Pepsico, Purchase, NY Ravinia, Chicago Swarthmore Festival of Music and Dance Symphony Space, NY - Scarlatti, Beethoven Marathons Tanglewood Music Center Summer Music Festivals (current) - Faculty and Performing Artist: The Banff Centre California Summer Music, Pebble Beach, CA Great Lakes Festival, MI Ravinia Steans Institute Sarasota Music Festival, FL Summerfest, La Jolla, CA Yale at Norfolk Yellow Barn, Putney, VT Summer Music Festivals prior to 1998: Bowdoin College Summer Music School and Festival Cummington School of the Arts New College Festival, Sarasota, FL Tanglewood Music Center (Chairman of Faculty) Banff Center for the Arts Jerusalem Music Center Other Professional Activities: Head of Keyboard Panel - International Conference on 20th Cent. Notation, Ghent, Belgium Judge - Three Rivers International Piano Competition (1978, 1979) Judge - Naumberg "Chamber Music Ensembles" Competition (1979) Visiting Committee - Dartmouth Music Department (1977) Trustee - Greenwood Music Camp (1974-1978) Judge - International Competition for American music for Piano (Sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation and Carnegie Hall, 1981) Member of the artist advisory board of Pro Musicus, an organization which sponsors and supports young musicians. Judge - Naumburg Piano Competition Judge - Naumburg Chamber Music Competiton Judge - Fischoff Chamber Music Competition Board Member of the Charles Ives Society Board Member of Ditson Fund (Columbia) Advisory Board - Orchestra 2001 (Philadelphia) Miller Theatre (Columbia University) Cover Photo Artist and article about my work in Clavier Magazine Feature Article about my work in Boston Globe Sunday Magazine Service at Stony Brook: Chairman of the Performance Faculty Member, Music Dept. Advisory Council Director, Contemporary Chamber Players Member, Concert Committee, UG Studies Committee; served on numerous other dept. committees; presently head of Dept. Chair Committee. Search Committees: Clarinet (chair), Flute (Chair), Voice, Conductor, Composer, Viola, Violin (Chair), Piano (Chair) Member of University Honorary Doctorate Committee for 3 years State University of NY Festival of the Arts Selected by SB music department students as Outstanding Teacher of the year in 1980. Recent Honor: Paul Fromm Award, presented by the Department of Music, the University of Chicago, in recognition of outstanding contributions to the performance and advocacy of the music of our time, April 2, 1995. Recent Recordings: Ludwig van Beethoven, Cello Sonatas and Variations, with Joel Krosnick, CD, Arabesque, Z6656-2 (1995). Bartok, Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, with Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, CD, Delos 3151 (1993). Charles Ives, Trio, with Yo-Yo Ma and Ronan Lefkowitz, CD, Sony SK 53126 (1993). Charles Ives, Songs, with Jan DeGaetani, CD, Elektra/Nonesuch, 9 71325-2 (1976, reissue 1990). Songs of America, with Jan DeGaetani, CD, Elektra/Nonesuch, 9 79178-2 (1988) "Kroslish Sonata," by Ralph Shapey, CD, New World Records, NW 355-2 (1978) |

© 1999 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded at the Ravinia Festival in Highland Park,

IL, on July 15, 1999. Portions were used (along with recordings) on

WNIB in 2000. This transcription was made in 2009 and posted on this

website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.