|

Colin Matthews, OBE (born 13 February 1946) is an English composer of contemporary classical music. Noted for his large-scale orchestral compositions, he is also a prolific arranger of other composer's music, including works by Berlioz, Britten, Dowland, Mahler, Purcell and Schubert. Having received a doctorate from University of Sussex on the works of Mahler, from 1964–1975 Matthews worked with his brother David Matthews and musicologist Deryck Cooke on completing a performance version of Mahler's Tenth Symphony. Colin Matthews read classics at the University of Nottingham, and then studied composition there with Arnold Whittall, and at the same time with Nicholas Maw. In the 1970s he taught at the University of Sussex. During this period he also worked at Aldeburgh with Benjamin Britten and Imogen Holst. His music has been published principally by Faber Music since 1976.

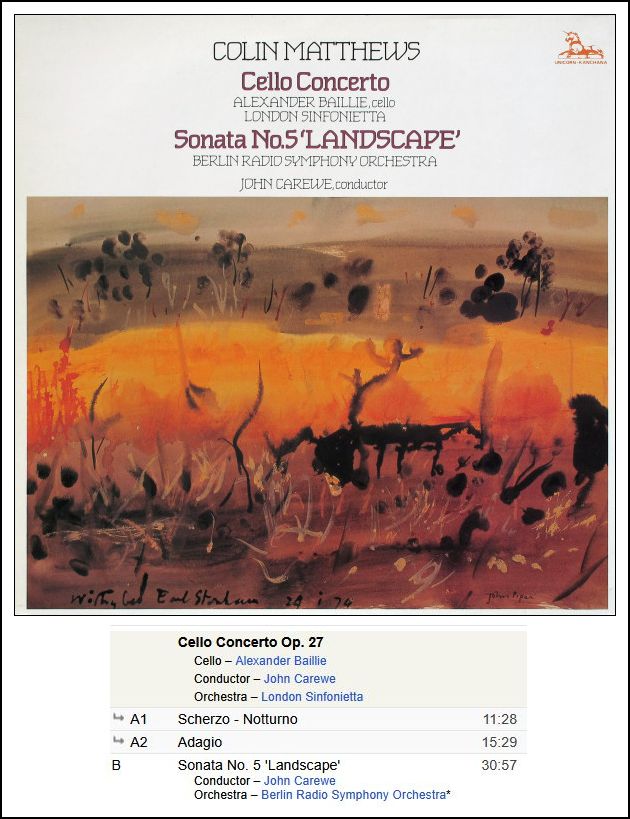

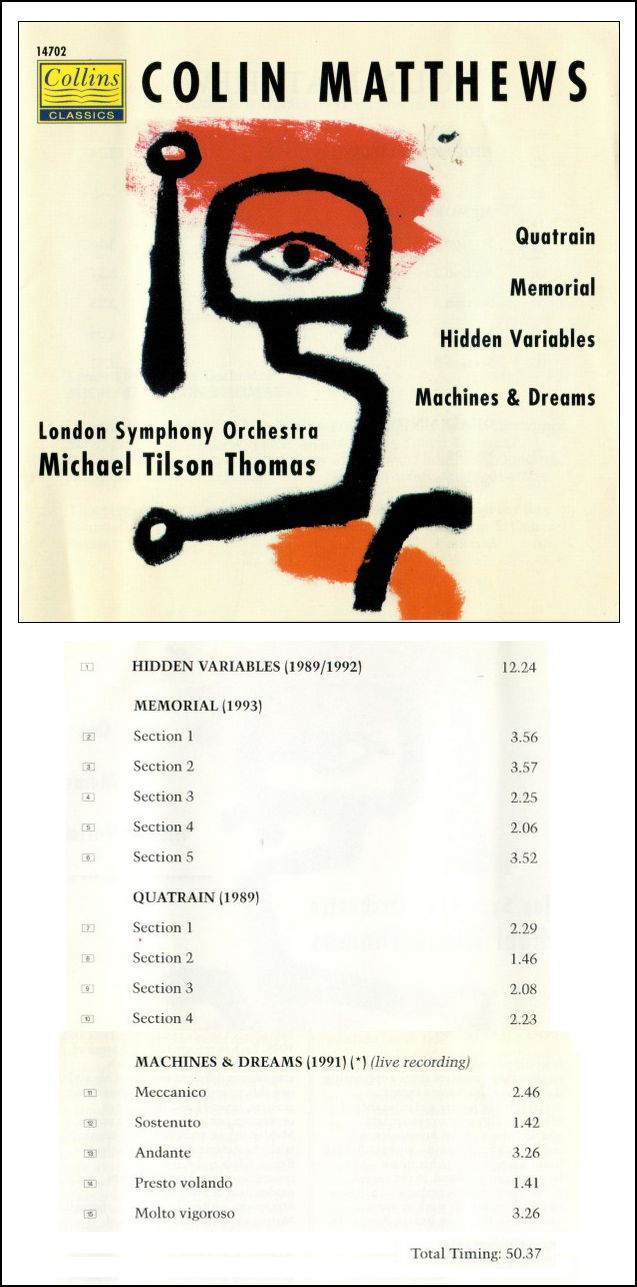

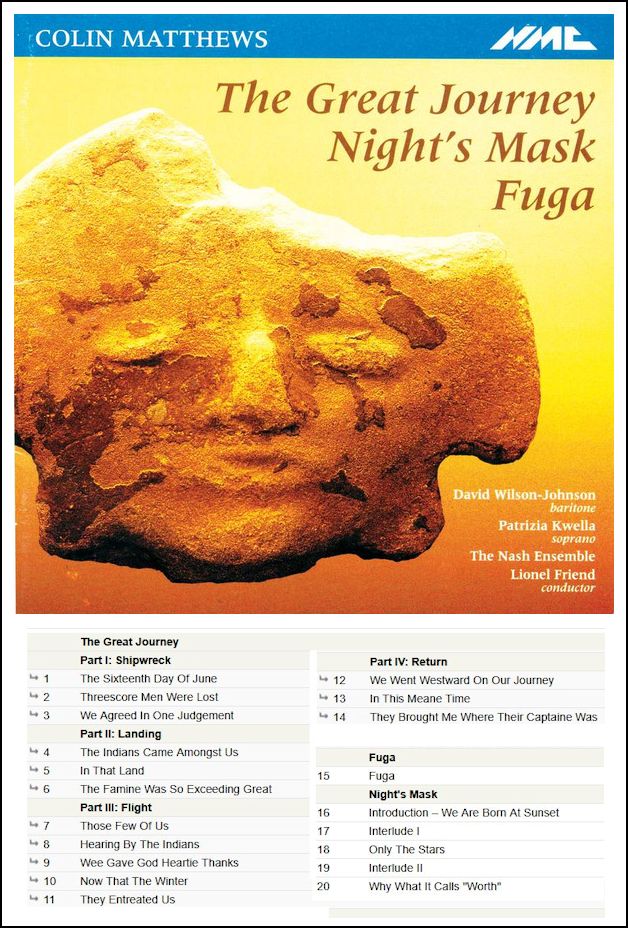

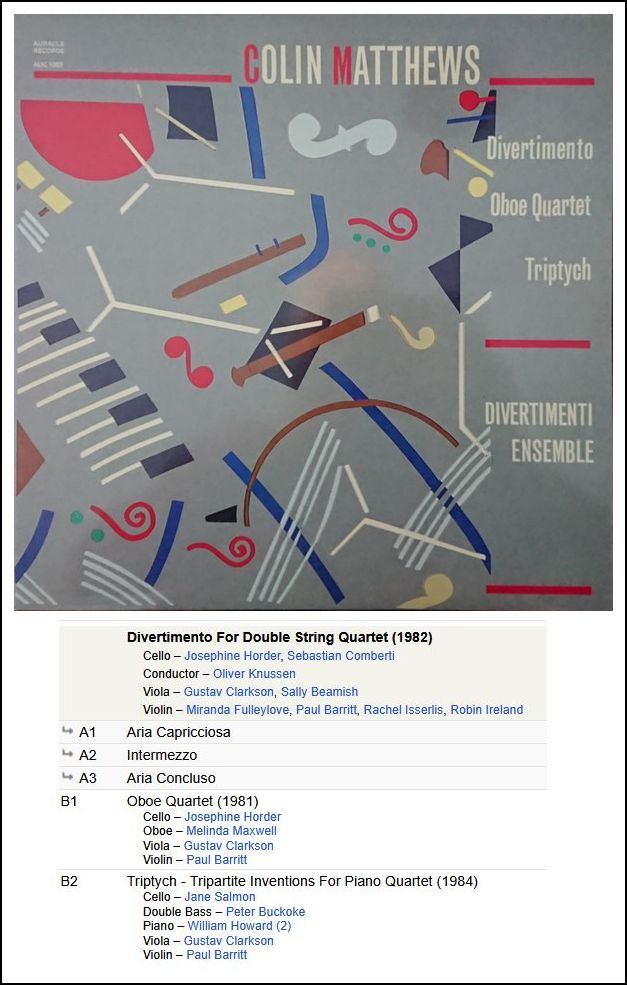

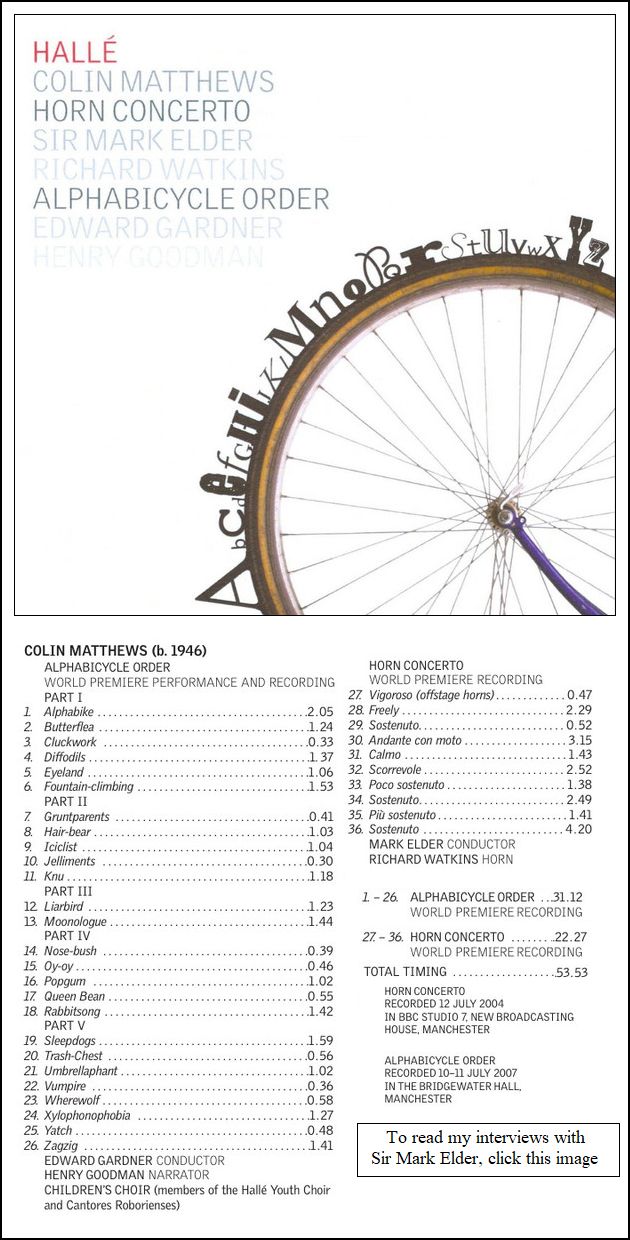

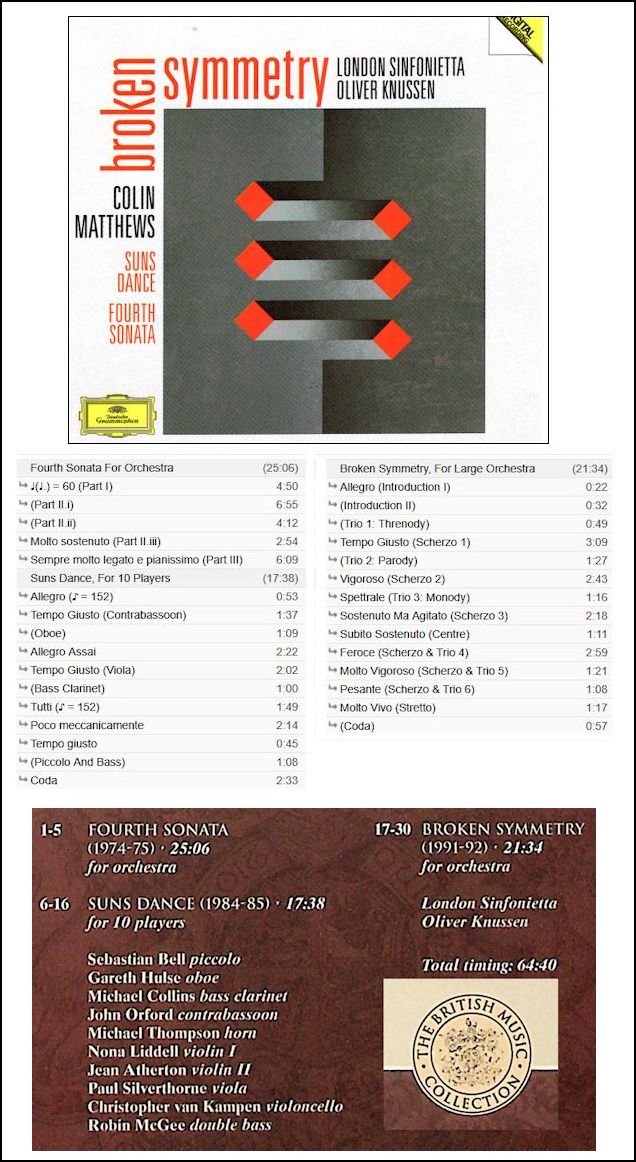

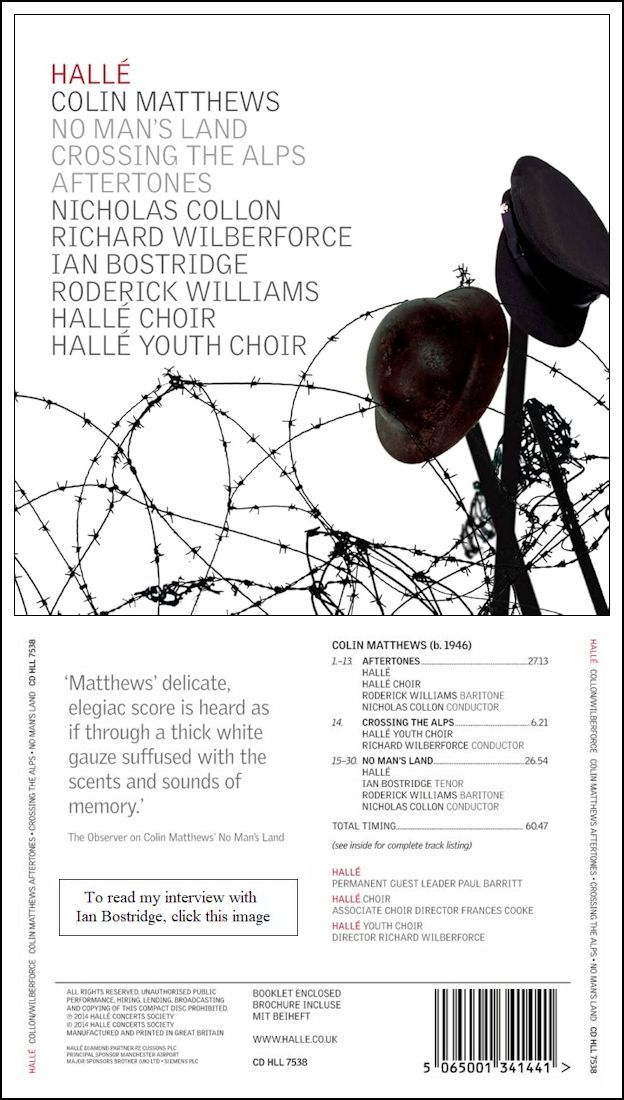

The BBC commission Broken Symmetry was first performed by its dedicatees, the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Oliver Knussen, in March 1992, and repeated at the 1992 Proms. It forms the third part of the huge choral/orchestral Renewal, commissioned by the BBC for the 50th anniversary of Radio 3 in September 1996. Renewal received the 1997 Royal Philharmonic Society Award for large-scale composition. The Dutch première of Cortège was given in December 1998 by the Concertgebouw Orchestra under Riccardo Chailly. The ballet score Hidden Variables, incorporating a new orchestral work, Unfolded Order, was commissioned by the Royal Ballet for the reopening of the Royal Opera House in December 1999, with choreography by Ashley Page. Colin Matthews' chamber music includes six string quartets, two oboe quartets, a Divertimento for double string quartet (1982), and a substantial body of piano music. Between 1985 and 1994 he completed six major works for ensemble: Suns Dance for the London Sinfonietta (1985, reworked for the Royal Ballet as Pursuit), Two Part Invention (1987), The Great Journey (1981–88), Contraflow, commissioned by the London Sinfonietta for the 1992 Huddersfield Festival, and two commissions for the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, Hidden Variables (1989) and ...through the glass (1994), the latter given its first performance under Simon Rattle, who also conducted it in 1998 at the Proms and in Salzburg. Matthews' music was featured at the Almeida Festival in 1988, at the Bath Festival in 1990, at Tanglewood where he has been visiting composer many times since 1988, at the 1998 Suntory Summer Festival in Tokyo, at the 2003 Avanti! Festival in Finland, and the 2004 Berlin Festival. He is founder and Executive Producer of NMC Recordings, and has also produced recordings for Deutsche Grammophon, Virgin Classics, Conifer, Collins, Bridge, BMG, Continuum, Metronome and Elektra Nonesuch (Górecki's Third Symphony, for which he received a Grammy nomination). Photos of a few of his recordings are used as illustrations on this webpage. He is active as administrator of the Holst Foundation, was Chair of the Britten Estate for many years, and is Music Director and Joint President of Britten-Pears Arts. He was a Council Member of the Aldeburgh Foundation from 1983 to 1994, and retains close links with the Aldeburgh Festival and the Britten-Pears School, particularly as co-director with Oliver Knussen of the Contemporary Composition and Performance Course, which they founded in 1992. He was a member of the Council of the Society for the Promotion of New Music Performing Right Society from 1992 to 1995. Since 1985 he has been a member of the Music Panel of the Radclffe Trust. He was an Executive Council Member of the Royal Philharmonic Society from 2005 until 2019.In 1998 Colin Matthews was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Nottingham, where he has been honorary professor since 2005. He is currently Prince Consort Professor of Music at the Royal College of Music, where he was made FRCM in 2007, and distinguished visiting fellow in composition at the University of Manchester. He was a governor of the Royal Northern College of Music (where he is FRNCM) from 2001 to 2008. In 2010 he was made an Honorary Member of the Royal Academy of Music. He was presented with the Royal Philharmonic Society/Performing Right Society Leslie Boosey Award in 2005, honoring an individual who has made an outstanding contribution to the furtherance of contemporary music in Britain; and the Gramophone 2017 Special Achievement Award in recognition of his work for NMC. He was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2011 New Year Honours for services to music. In 2024 Matthews was nominated for an Ivor Novello Award at The Ivors Classical Awards. Matthews and his wife Belinda, a former publishing executive at Faber and Faber, have three children, Jessie, Dan and Lucy. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

© 2006 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 23, 2006. Portions were broadcast on WNUR the following month, and again in 2015; and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2007, and 2009. This transcription was made in January of 2026, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.