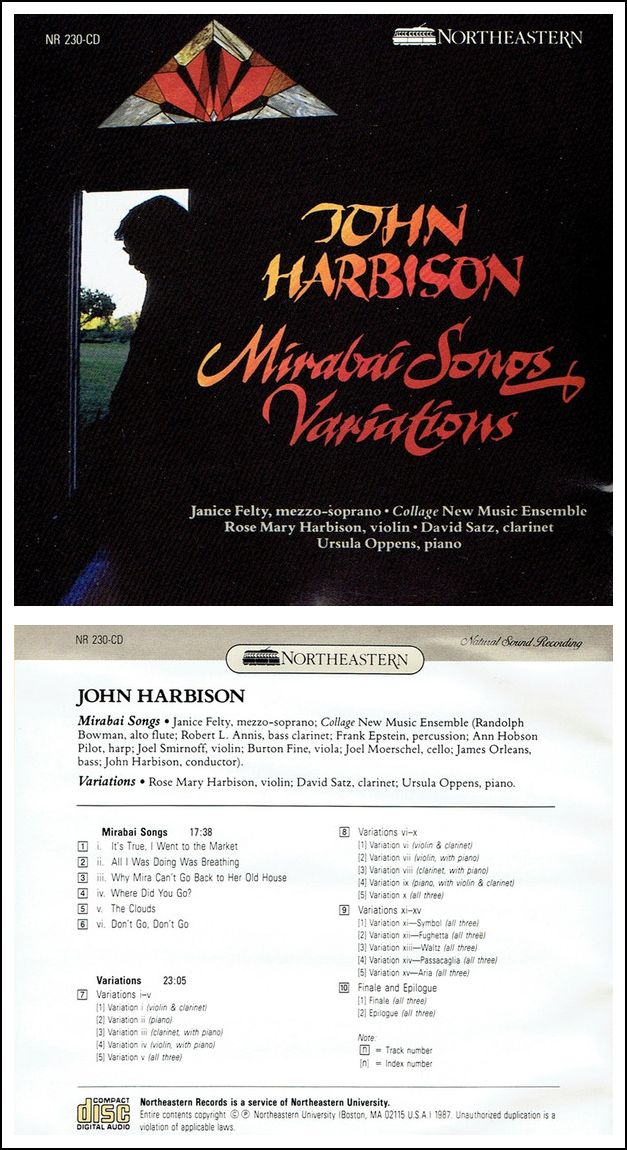

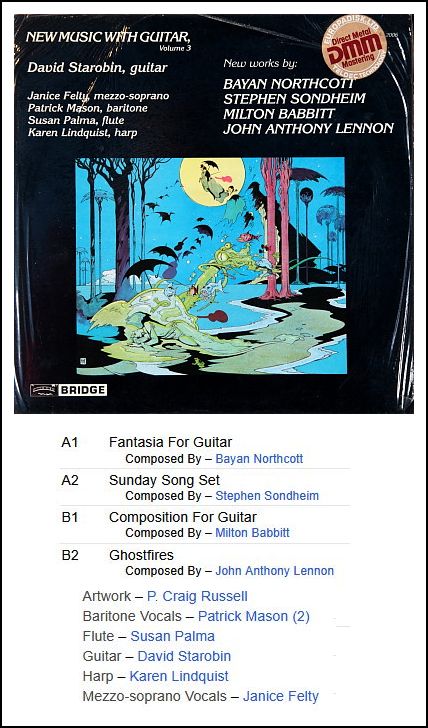

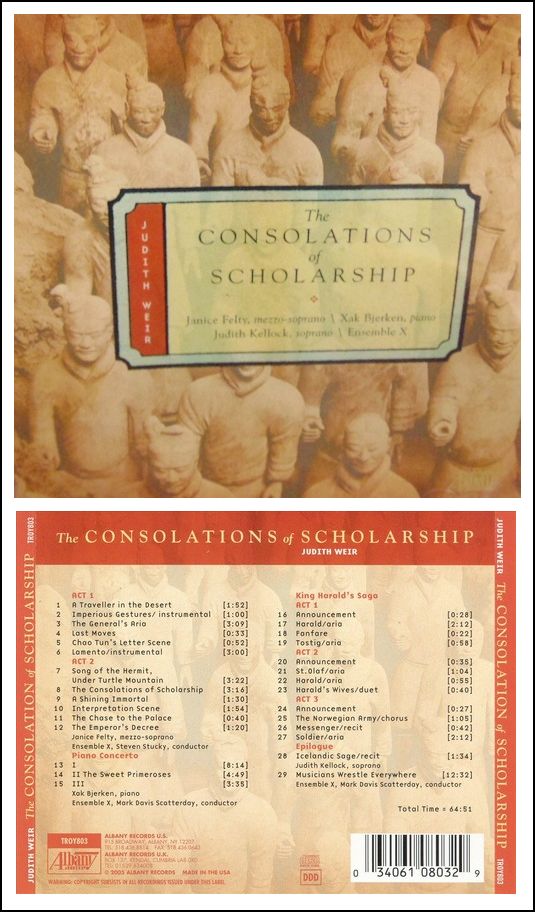

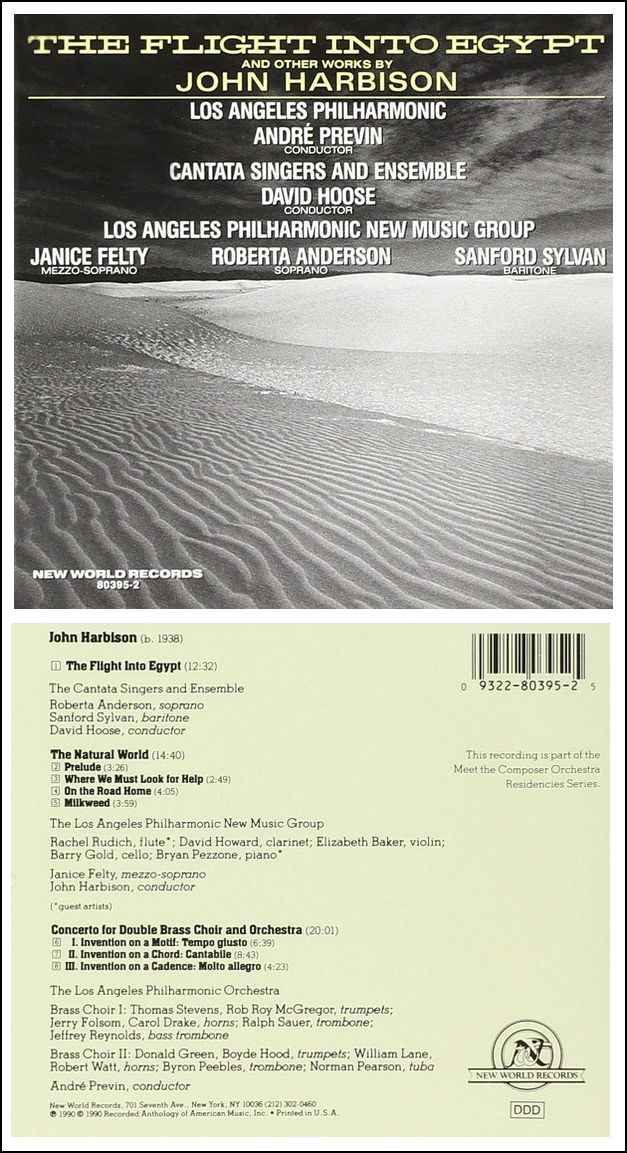

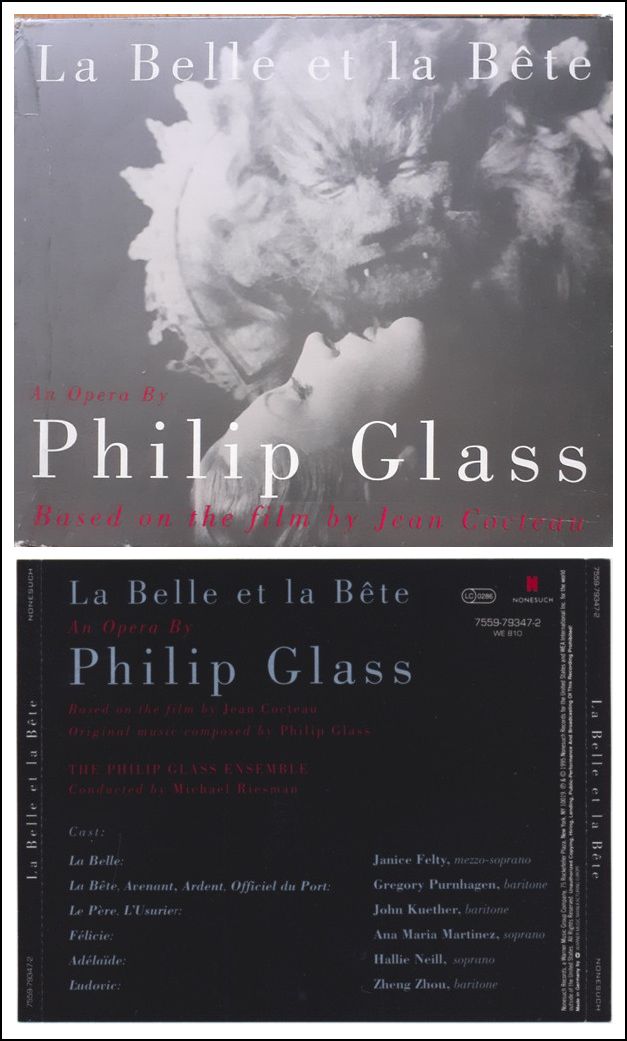

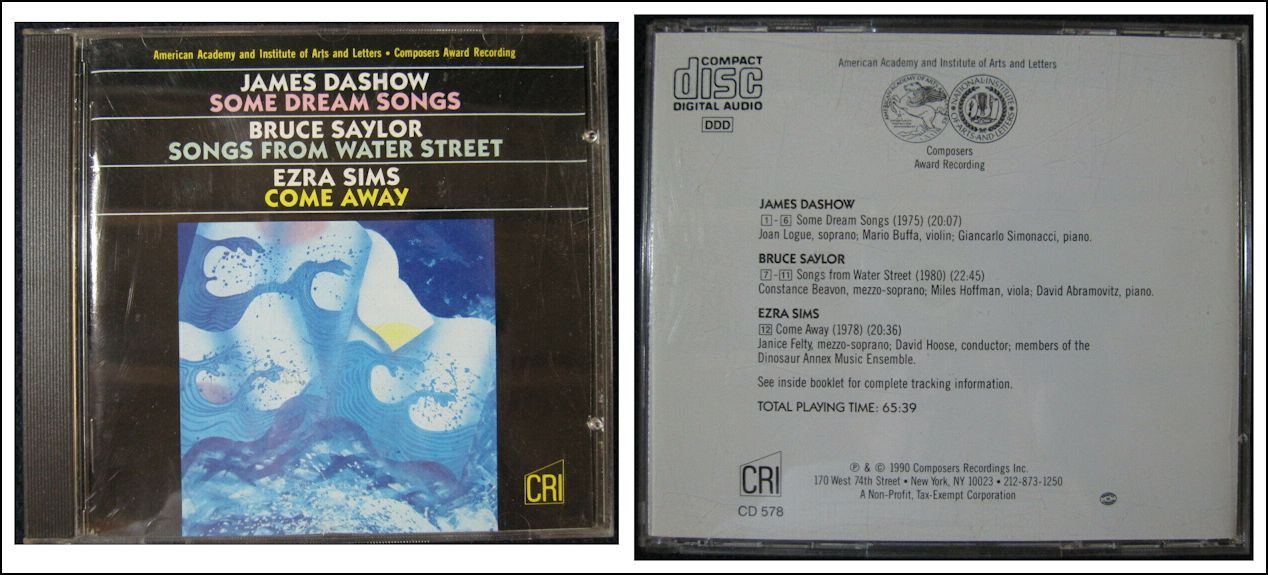

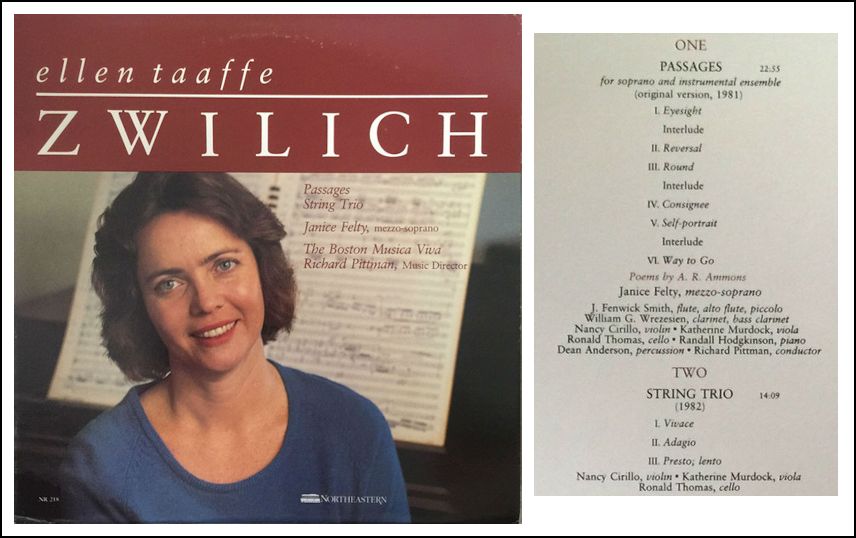

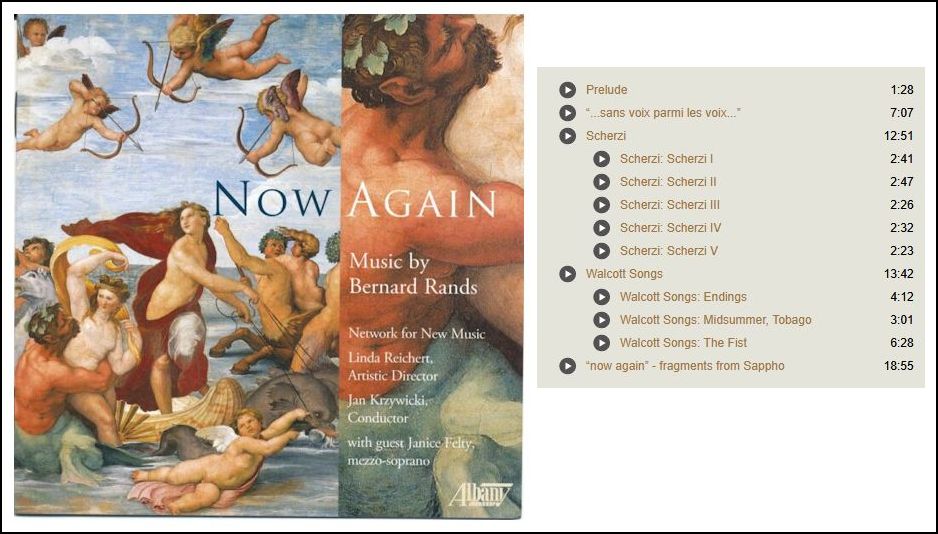

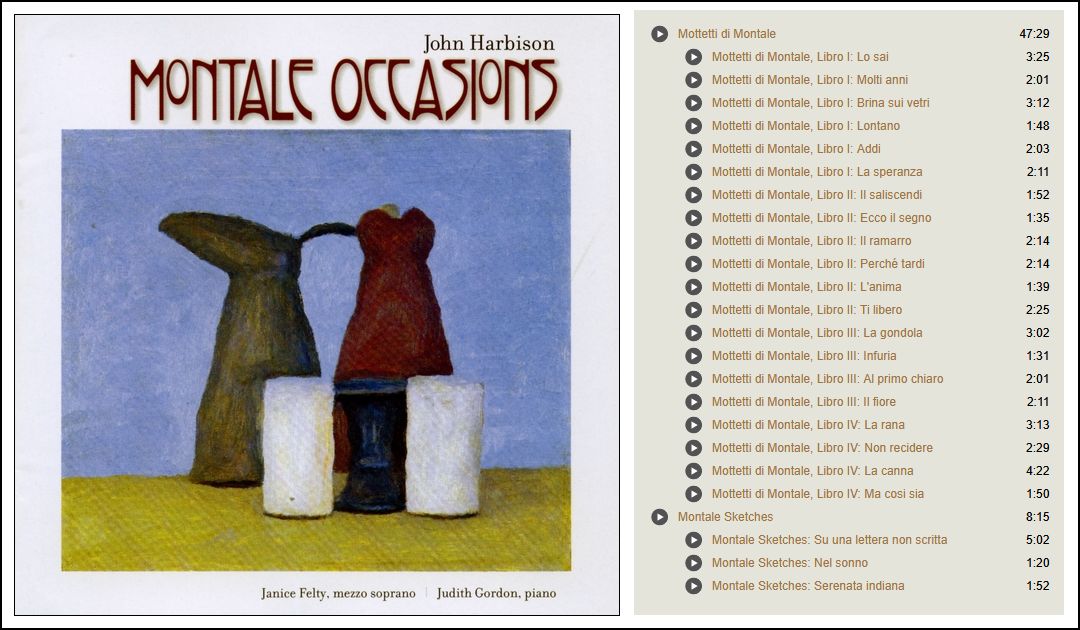

Janice Felty (born August 23, 1947) is an American operatic mezzo-soprano,

known

for her interpretations of contemporary composers including John Adams, Philip Glass, John Harbison, Lee Hoiby, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich,

and Judith Weir.

Janice Felty (born August 23, 1947) is an American operatic mezzo-soprano,

known

for her interpretations of contemporary composers including John Adams, Philip Glass, John Harbison, Lee Hoiby, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich,

and Judith Weir.

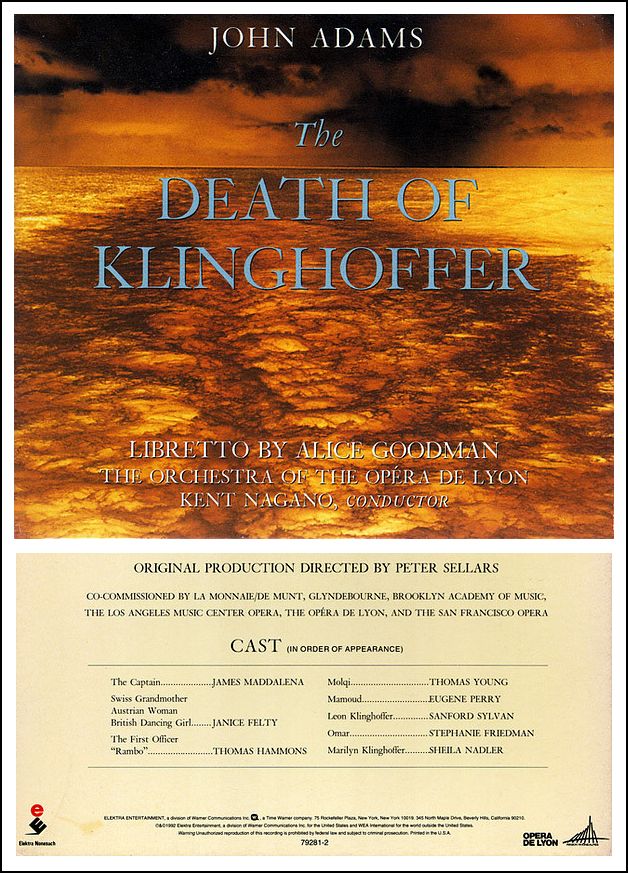

Besides new works, in 1987, Felty played the title role in the Handel oratorio Athalia at Symphony Hall in Boston with conductor Christopher Hogwood, and she sang Dorabella in Così fan tutte of Mozart in the Vienna production directed by Peter Sellars, which is available on Decca DVD. In 1991 Felty premiered several roles in John Adams' The Death of Klinghoffer and recorded this work for Nonesuch Records.

She appeared in the première of Steven Stucky's To

Whom I Said Farewell with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the composer

conducting, Haydn's Arianna a Naxos with the Santa Fe Chamber Music

Festival, and Colin Matthews’ Continuum with the Los Angeles Philharmonic

under Esa-Pekka Salonen.

They then repeated the Matthews work with the Chicago Symphony's MusicNow

series.

== Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD