Backstage at Lyric Opera

of Chicago

Production Stage Manager

Caroline Moores

== and ==

Stage Manager

John Coleman

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Most of the interviews I have done are with musicians who are visible

to the audience during their performances. I have also met a

few directors and managers, and even a few critics. In 1998,

it was suggested to me that I do a series of programs featuring some

of the unsung heroes who live and work backstage at Lyric Opera of Chicago.

They are truly the ones who keep the shows running, and provide

the performers with what they need in order to bring each work to life.

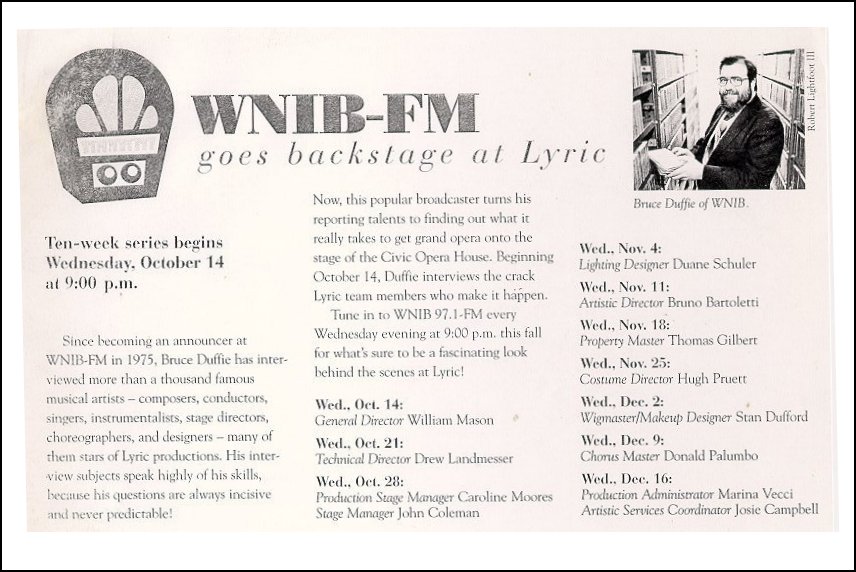

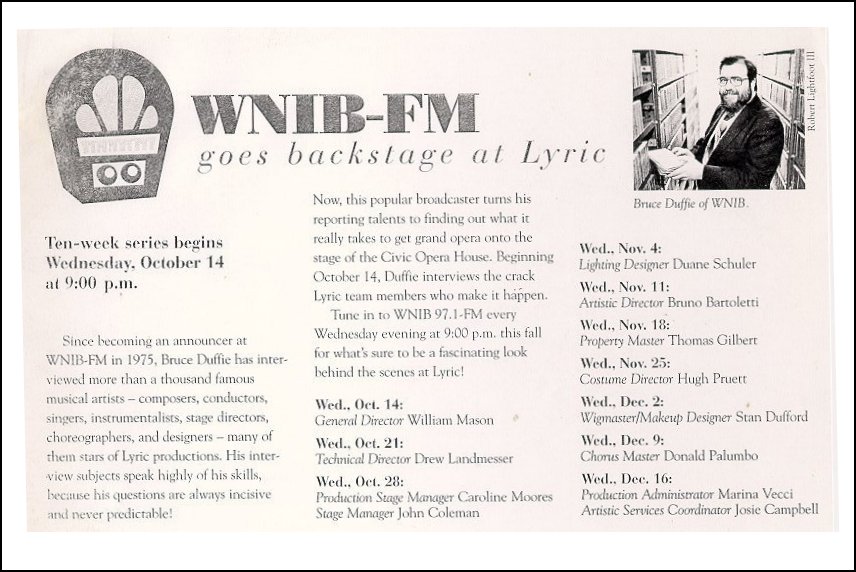

As can be seen from the advertisement shown below-right,

the ten programs gave a well-rounded view of these important people.

The series ran on WNIB, Classical 97, from mid-October through

mid-December of 1998, and was repeated in early-January through mid-March

of the following year. It was a fine success, and brought many

positive comments from listeners.

Many of my interviews have been transcribed and posted on

this website. This one, with two stage managers, and another with two administrators

complete the series. It is obvious from this conversation that

these two work well together, and their enthusiasm shows just how

much they loved their jobs and looked forward to every situation.

As we settled in to begin, Ms. Moores commented that she does

not seek publicity . . . . .

Caroline Moores: We’re not usually interviewed.

We don’t usually have to explain what we do, we just do it.

John Coleman: [Laughs] We’re not

really sure sometimes what we do!

Bruce Duffie: Should the public know what

you two do?

Moores: No, absolutely not.

BD: Why not?

Moores: Because if they know what we do,

it means something has gone terribly wrong.

BD: Even when you do it brilliantly?

Moores: [Laughs] No. If we

do it brilliantly, nobody knows that somebody is doing it.

Coleman: Our goal is to give as much as

we can contribute to this, and to make sure that the public is taken

in by the production that they’re seeing and hearing, so that they’re

completely wrapped up in it, and in not any of mechanics or technical

aspects of the show.

BD: Are you two the ones that provide

the magic? [Vis-à-vis

the program announcement shown at right, see my interviews with William Mason, Drew Landmesser, Duane Schuler, Bruno Bartoletti,

Thomas Gilbert,

Hugh Pruett, Stan Dufford, and Donald Palumbo.]

Moores: We don’t provide it, but we make

it happen.

Coleman: I’d say we’re like oil in the

works, and as long as the machinery is running smoothly, no one notices

that we’re there. But if the machinery breaks down, then they

know.

Moores: We organize everything in the

rehearsal process, and then do it in the performances. We are

the ones that call all the cues. When the house curtain goes

up, one of us is saying,

“Go!”

and when a follow-spot picks up somebody, that’s us saying, “Spots

warning on picking up the man with the hat and the huge feather.

Follow him until he jumps off the balcony.”

BD: In La Bohème, do you

say, “Follow the man with the hat with the huge

feather,” or do you say, “Follow

Shaunard”?

Moores: It depends.

Coleman: Usually the first time you say,

“Follow the man in the hat and the feather,”

because they won’t know...

Moores: ...that Shaunard’s the one in

the gold brocade coat.

BD: I just wondered how much the stagehands

and the lighting people who are running the spots, get involved in

the action and the characters.

Moores: They’re brought in quite late

in the process. We don’t add follow-spots from a bridge until

we have a piano run-through, which is also when we add costumes and

lighting. So, up to that point, unless they’ve

done the production before, the follow-spot operators have no idea

who is who, and who they’re going to pick up, and what the action is.

So, there’s no point in saying, “Pick up the

Count!” because anybody starting at that stage

who doesn’t know who the Count is, wouldn’t be able to pick him up.

BD: When you bring a production back,

do you try to get the same follow-spot operator?

Moores: It’s nice if it happens that way,

but it rather depends on who is working in the season. It doesn’t

always happen.

Coleman: These stagehands here are fabulous.

They really know what they’re doing, and they pick it up very quickly.

Moores: Absolutely!

Coleman: They need little instruction,

and we’re fortunate to have such good people to work with.

BD: The two of you seem to work together

very well. Do you both do the shows, or does each one of you do

your own shows?

Moores: Each one of us does a show.

John usually calls four productions in the season, and I usually

do three. There are eight in total in our season...

Coleman: ...and she runs the department.

Moores: One of the other assistant

stage managers sometimes is blessed with getting a show to call.

BD: Is that to give them experience?

Moores: To give them experience, and also

to help us...

Coleman: ...to balance the workload...

Moores: ...and the schedule.

BD: [With mock horror] You mean,

you want a day off???

Moores: [Laughs] Yes!

Coleman: We’d like two, actually! [More

laughter]

Moores: We would like consecutive days

off, but we don’t have them very often.

Coleman: Saturday and Sunday would be

nice, but I think that would probably be prohibited. [Both laugh]

BD: I worked for fifteen years before

I got two days in a row off, so there you are!

Moores: You must love what you do.

BD: That’s right, and that seems to be

the common thread among everybody that I’ve talked to backstage.

It’s obvious with the singers and the conductors, but the backstage people

also love what they do.

Moores: Absolutely!

BD: They love being here. Why is

Lyric Opera special?

Moores: I think the scale of it.

It’s an international house. Who could not enjoy working with

the world’s greatest?

Coleman: They hire the best singers, the

best directors, and the best conductors. They have a fantastic

chorus, a fantastic orchestra, the best stagehands that there are,

and really it’s such a pleasure to be involved in a creative process

that presents this caliber work.

BD: What is it that makes someone the

right person for this job?

Moores: For stage managing?

Coleman: You need organizational skills...

Moores: ...and you need patience, and

a sense of humor...

Coleman: ...and a good temperament.

You need to be able to think on your feet, and be creative in terms

of dealing with difficult situations, and making decisions quickly.

BD: Sounds like you are part traffic-controller

and part psychologist.

Moores: Yes!

Coleman: I’d say it’s very close to traffic

controlling, with temperamental highlights. [All laugh]

Moores: And you have to love working with

people. Ultimately, that is what our job is. A stage manager

facilitates, and is the liaison, and if you don’t love people, how

can you do that job?

BD: But you must also love the opera,

too.

Coleman: [Thinks a moment] We love

some of the operas. [Both laugh]

Moores: I don’t think I grew up loving

opera, nor was I drawn to this kind of work because I loved opera.

BD: Then why were you drawn to this?

Moores: The scale, the organization that

you become a part of, and the challenges of making things work. It’s

very satisfying when something goes well, and to know that it was because

you did your job well.

BD: Does it usually go well?

Moores: Yes, it does, and in this house

particularly it usually goes well because of the caliber of artist.

That means everybody with whom we work.

Coleman: Even when it doesn’t go right,

everybody covers for it very well, and the audience usually doesn’t

know that something’s happened.

BD : I assume when something doesn’t go

right, it’s just a small item, rather than something disastrous happening.

Coleman: Sometimes you’ll have a power

failure. The lights will go out, and then come back on.

This is a problem with the technical equipment.

BD: [With a wink] That, of course,

is completely your fault! [All laugh]

Coleman: Absolutely!

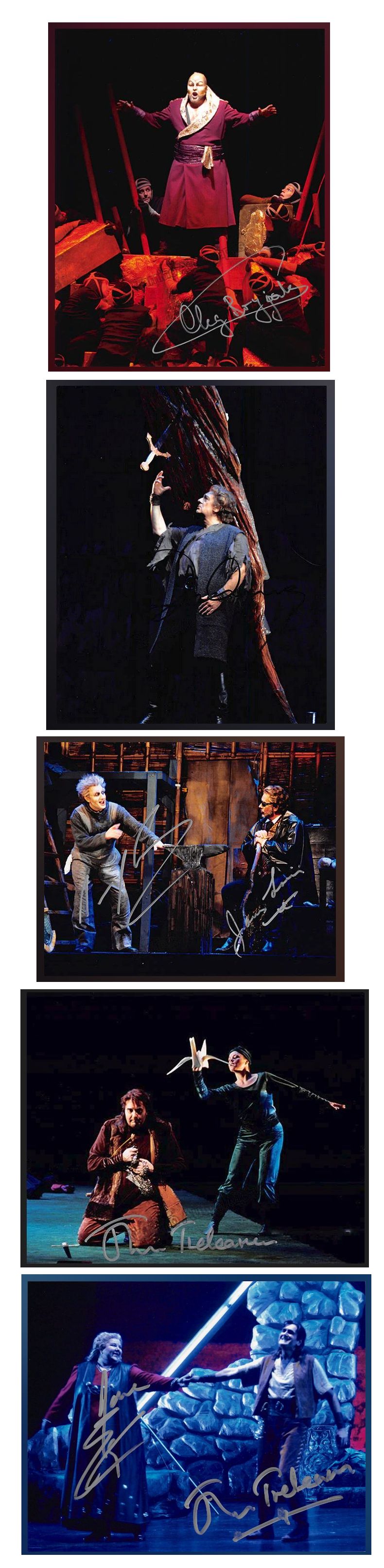

Moores: That’s right! For Madama

Butterfly that we did last season [sequence of photos shown

at right], almost the entire set was a turntable, and for one performance

the turntable stopped working. The stagehands went out on stage

in coveralls, and sat on the upstage edge of the turntable. They

assisted the turntable as it moved, and I don’t think the audience for

a moment knew that it had happened. All the moves from the middle

of the first act to the end of the opera worked in that way.

BD: Was there lots of grumbling that the

thing was too heavy?

Moores: No. Actually, the grumbling

from the stagehands was simply that they had to be there for so long.

They were trapped on stage for almost the entire opera. It wasn’t

a good thing. We tried to cheer them up by playing charades,

and miming things as a film or a book. It was entertaining. [More

laughter]

* * *

* *

BD: You have to call everything.

I assume that everybody, especially toward the end of the run, anticipates

these calls, and knows they are coming.

Moores: They know they’re coming, but

they always wait for the stage manager, and the magic word is, “Go!”

They may know what they’re going to do, but they are highly trained

to wait for that word.

Coleman: It’s a team effort. Everybody

covers for everybody. Like if something is off, they’ll ask,

we will take care of it. You’re really part of a big process.

BD: But it’s your judgment, and then you

might have to delay a cue very slightly if something is not in place?

Or if the tempo is a little slower one night, you have to delay a little

bit?

Moores: Absolutely.

Coleman: Sure.

BD: You’re always following a score?

Coleman: Yes.

Moores: We work off a piano-vocal score.

The stage manager puts every cue in a score.

BD: Is there music on both sides of the

page, or do you separate it so there’s music just on one side?

Moores: We usually do music on both sides.

The assistant director would usually have a book that is blank on

one side and music on the other, because he has to record all the blocking,

and needs far more room to write. But for cues the stage manager

gives, we are far more tied to the music.

Coleman: That way you’re not turning so

many pages so quickly when you’ve got a lot of cues, or the music is

going very quickly.

BD: Are there ever times when there are

too many cues coming too thick and fast?

Moores: Not too many. But we love

lots of cues.

Coleman: You figure it out. That’s

part of the challenge and part of the real excitement, and the best

part of the job is putting it all together.

BD: Is there ever a time when you wait

five minutes between cues?

Moores: Oh, yes!

Coleman: Sometimes longer!

BD: I would think there would be some

subtle change, or someone to call from off stage.

Moores: If you’re lucky you might

have a singer to call to stage.

Coleman: In Capriccio, it just

started and everyone was there, and you just kind of waited until

the end to do something.

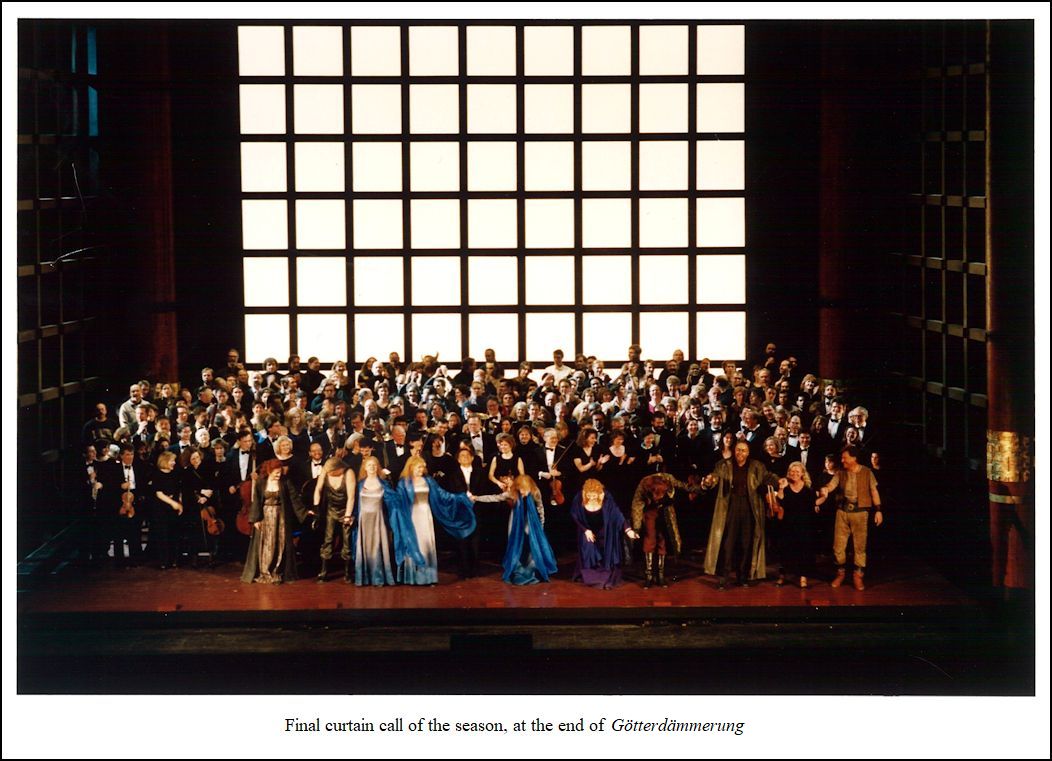

Moores: In Götterdämmerung,

the first act is an hour and a half, but I don’t remember how long

we have to wait for the first scene-change.

BD: Can I assume the rest of the Ring

was rather tedious for you?

Coleman: It kept going.

Moores: No, I would never describe the

Ring as tedious.

BD: ‘Complicated’

is perhaps a better word?

Moores: Complicated, yes, but never tedious.

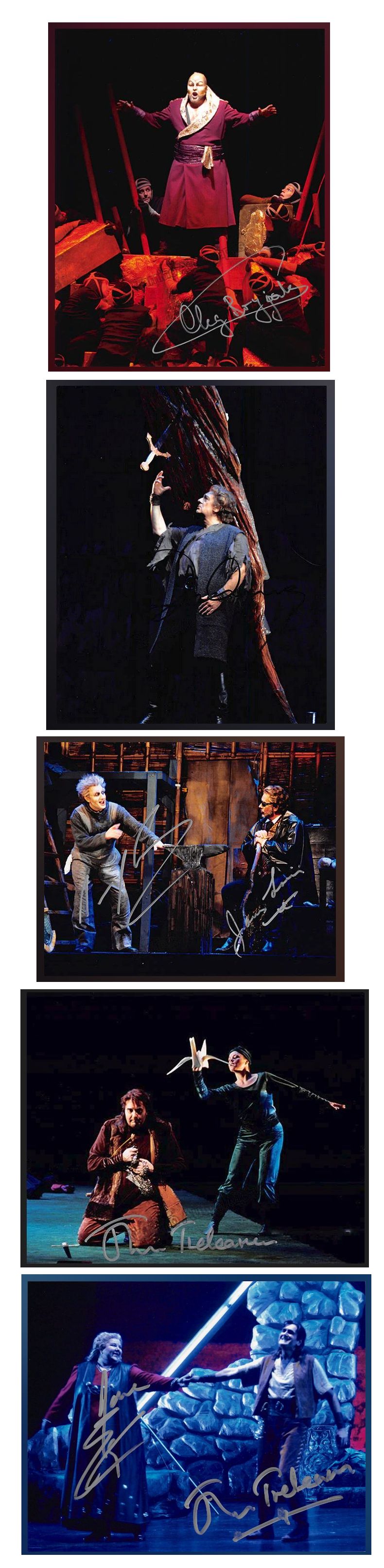

[Shown at left is a sequence of photos from the Ring. Rheingold,

Walküre, Siegfired (two photos), and Götterdämmerung

(top to bottom) Also, see my interviews with David Cangelosi (Mime),

James Morris (Wanderer),

and Jane Eaglen (Brünnhilde).]

BD: What would you rather have, cues that

come thick and fast, or long breaks between them?

Moores: Thick and fast! Wouldn’t

you?

Coleman: Yes, thick and fast, but I like

it broken up, with not every show being thick and fast.

Moores: Yes.

Coleman: Sometimes it’s just nice to do

something that’s just a big old-fashioned opera, where the curtain

comes in and the curtain goes out, and you listen to great singing

and change the set only once an act. [All laugh]

BD: You then change the set during the

intermission when you have plenty of time.

Moores: Yes, that’s right, when you can

sneak away for a cup of coffee for five minutes.

BD: Are you the one with a stopwatch, to

make sure that the intermission is exactly however many minutes long

it is supposed to be?

Moores: Yes, that’s the stage manager.

In the performances, we also call the chiming. We’re responsible

for saying, “Chime Number Two out in the lobby”.

Coleman: Also, really in some ways we

are the first person on the firing line if something happens. We

try to solve the problem creatively, but you get a lot of hell.

Usually, we’re the first ones to react.

BD: Is it correct though to assume that

when something happens, you stay at your position and direct other

people to make the corrections?

Moores: Generally.

Coleman: Yes, that’d be right.

Moores: During the performance, the stage

manager is on a headset, and has any number of people to talk to. From

the stage manager console, you can also page through the building. So

if you need wardrobe right away because Miss Malfitano’s dress

has ripped, you can just page it so that wherever the dresser is, they

hear you and can come running to stage right or stage left, wherever

you need you them. You just say over the paging system to bring

safely pins or whatever.

BD: Of course, you would be the one who

would know where she’s making the exit.

Moores: Exactly, where she’s exiting and

where she’s entering, and how much time there is to sort something

out.

Coleman: It is important that once something

happens, not to let something else happen that you have to keep your

eye on, because it can domino. One thing happened, and if you

focus on that too much, then all of a sudden you’ve missed something

else, and then...

Moores: Yes, if you’re paging for wardrobe

while you should have been bringing a curtain in.

Coleman: It’s not such a good thing!

Moores: No!

BD: Where exactly is your position? Where

do you stand?

Moores: Downstage right.

Coleman: That depends on where you are, and

in which opera house, but here that’s where we are situated.

Moores: It’s to the left side of the

stage if you’re sitting out in the house.

BD: When the conductor goes into the

pit, you are right above him?

Moores: Exactly. We’re the last

person he sees as he enters! [Laughs]

BD: Sounds like an execution! [Gales

of laughter] Do you feel like you’re sending someone to their

doom?

Moores: No, very seldom! [More laughter]

BD: Do you know ahead of time that the

show is going to run properly, or are there ever nights when you don’t

know if you’re going to make it to the end three hours later?

Moores: You’ll always get to the end because

you have to.

Coleman: [Smiles] Except the end

of the Ring. You never know that you’re going to get to

the end. You look up and it’s nine o’clock, and you’ve been there

for three hours, and you’ve two more hours to go! [Much laughter]

Moores: But one of the wonderful things about

live performance that you never know is that the energy which comes

from the audience and the performers can be so different. There’s

no explaining it, but there are times when you have a show that is just

so good. Everything gels, and you know this is why I’m doing opera.

Then you’ll have another performance where things are just slightly

awful. Something doesn’t quite work, and then something else doesn’t

quite work. You can’t explain it, and you can’t really predict it.

BD: Yet those might be the nights when

you get the tremendous ovations.

Moores: Exactly. You never know

what is sent from the stage to the audience in terms of what they pick

up.

* * *

* *

BD: Have you worked in theater also as well

as opera?

Moores: I haven’t. Have you, John?

Coleman: Yes, I have.

BD: What’s the difference?

Moores: It’s quieter because there is

no singing. [Much laughter]

Coleman: Right, that’s true. Opera is

first and foremost a musical artform, and theater is dramatic. It’s

about the text and the actors. So that’s the major difference.

BD: [Only somewhat seriously] Can

we not assume that when the stage director comes in for an opera, as

far as he’s concerned the most important thing is the theater, and to

hell with the singing?

Coleman: Some stage directors use that

as a tactic to get things they need, but all the good stage directors

know that if you don’t have good singers, then you’re not going to have

a good production regardless of how brilliant your concept is, and how

brilliant they are at acting. If they can’t sing the role, it’s

still not going to be a success.

BD : How early in the production process

do you get involved?

Moores: In this house, we really don’t

get involved until a few weeks before opening night. Casting in

the opera world is done so far in advance that we’re seldom in on auditions.

In the theater world, usually a stage manager would be involved

in auditions.

Coleman: This is to organize and facilitate

it. Also, the process starts a lot later in the theater.

They decide to do a show early on, and you may not come in until it’s

designed, but you’re there basically from when the casting is done, which,

at least in regional theater, is quite closer to the time that you’re

going to start rehearsals.

BD: When you come into an opera, what

is going on?

Moores: Usually we’re in a week or two before

the first rehearsal starts. However, in this house we have a summer

tech period, where we put each production on stage for a week, and

light it, and look at all the scenery, and sort out a lot of issues that

have to be taken care of before the production comes back in the season.

Coleman: There’s no time during the regular

season to spend a week teching, unless you’re wanting to do it between

Midnight and 8 AM. This is actually a great advantage in some ways

because the stage director and the designer can see their product early

on, and understand what it looks like and how it works. On the

other side, how do I know where I want light cues when I haven’t even staged

this yet?

Moores: The use of the summer tech varies

a little, depending upon the team of designer and director.

But usually the stage manager is there for that week.

BD: So anytime there’s anything going

on on the stage, you are there?

Moores: Absolutely, yes. Then after

that tech week, we don’t see the production again until the first

day of rehearsal. Then the stage manager is there from the beginning.

BD: From the first day of onstage rehearsals,

or in the rehearsal room?

Coleman: Wherever they happen to be.

Moores: We’re there for every rehearsal,

every staging rehearsal, and every performance.

BD: Are there times when you tell the director

something can’t be done?

Moores: Absolutely! That’s part

of our job.

Coleman: But sometimes they don’t care,

so we say it’s okay!

Moores: We might phrase it differently,

because it’s better not to say they can’t do something. That’s

the psychology bit coming in.

Coleman: You must have great tact from

time to time.

Moores: Yes.

BD: Without giving any specifics, are there

times when things just can’t be done, and the director says it must

be done, and there is impossible conflict?

Moores: There’s often conflict, but that’s

a very positive thing in the process, because from conflict comes resolution

and also development. There is sometimes conflict that can’t be

resolved in the way that perhaps the stage director wants, but there’s

always a way to solve it.

Coleman: Usually, we really can’t make a

decision about what the stage director wants. It’s not in our

purview to go ahead and change the set around. That’s someone else’s

job, so we find the people and get them together so they can discuss it.

BD: You page the right person, and get them there?

Moores: [Laughs] Yes!

Coleman: Or we’ll set a meeting with the

general director.

BD: How often do meet with Bill Mason [the

General Director]?

Moores: We don’t have regular meetings.

He stops in to rehearsals every so often, but usually

there’s somebody else that we need to go to before it goes to Bill.

Coleman: He likes to keep an eye on everything,

and he’s frequently in rehearsals. He’s certainly there for

all the Sitzprobes, and the orchestral rehearsals on stage,

and the piano dress rehearsal, which we call a piano run-through. [A

Sitzprobe, literally a seated rehearsal, is often the first rehearsal

where the singers sing with the orchestra, focusing attention on integrating

the two groups. When the performers stand or do blocking, it is

called a Wandelprobe.]

BD: In the middle of a rehearsal, how difficult

is it when the director says he’d like to go back five pages, and you

have to reset everything?

Moores: Oh, that’s not difficult. We like

that.

Coleman: As long as it’s not every five

minutes that you go back! [Laughter]

Moores: It’s part of our job to know at

any moment where anything this, and where it should be.

BD: Absolutely everything on the stage?

Moores: Pretty much, yes.

Coleman: They are our rehearsals, too.

So we make mistakes, and that’s how we learn.

BD: Is there ever a night when everything

is perfect?

Moores: Yes, of course. We’re professionals.

[Much laughter]

Coleman: I don’t know if it’s ever perfect,

but sometimes it’s really, really good.

BD: I hope it’s really, really good most

of the time.

Moores: Yes, it is.

Coleman: I think so, yes.

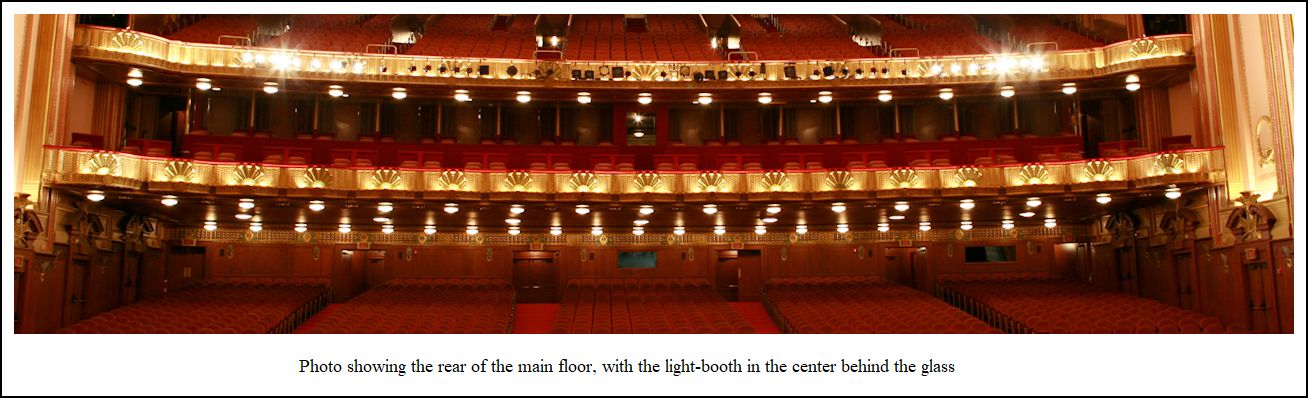

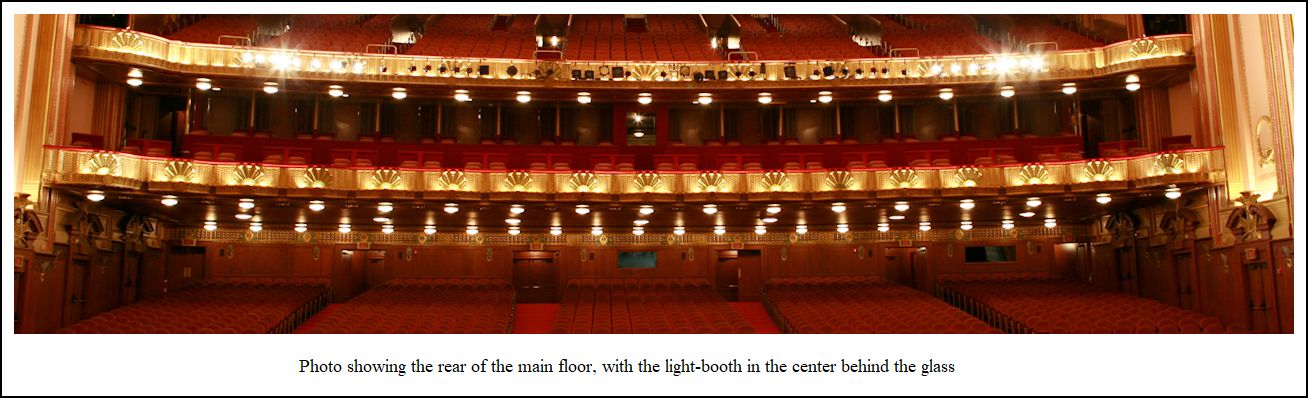

BD: Are you conscious of the audience

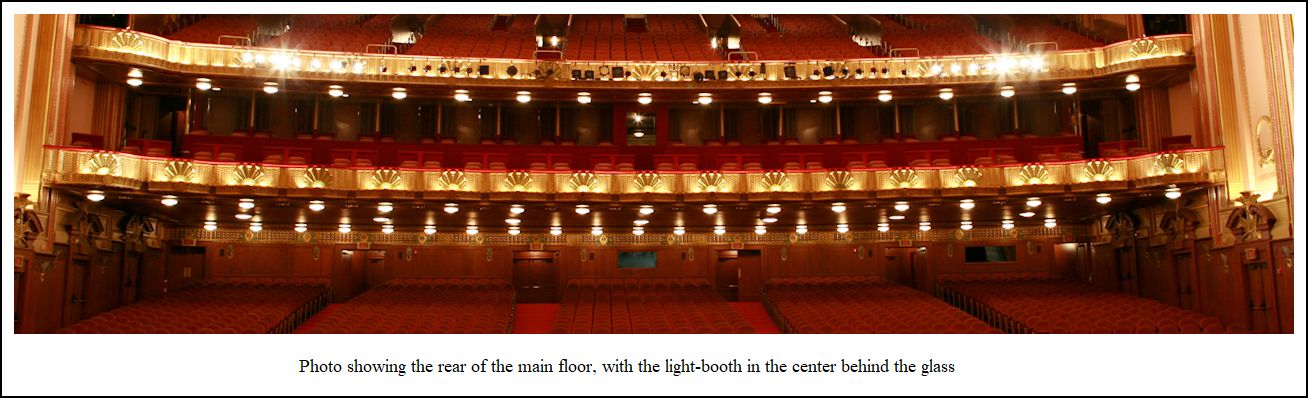

of 3,600 that’s out there watching? [Photos at left and below-right]

Moores: I’m not, actually. I find I get

the most nervous about the final dress rehearsals, and then after that

I don’t think about there being all those people out there. I am

just so focused on what we have to do.

Coleman: I would only think about them

when there’s a temperature difference between the house and the stage,

because the curtains are going to blow a different way.

BD: Many, many years ago, the old curtain would

occasionally billow out like a huge sail.

Coleman: Right, it goes each way sometimes

so that’s when I notice the audience the most. Also, on the opening

night, the intermissions can never be as short as they’re supposed to

be because everybody is having free champagne in the lobby and they don’t

want to come back to their seats.

Moores: Actually, it was like that for

the Ring cycle. In Das Rheingold there was no intermission,

so that was easy.

Coleman: It was perfect that way.

Moores: For Valkyrie, the audience

was pretty good about coming back. By Siegfried, they’d

started to know each other because they were all sitting in the same

seats, so they would talk to one another. Then by Götterdämmerung

it was impossible to get the audience back. [Laughs] Instead

of the chime being eight minutes before the start of the next act, we’d

have do it at ten to try to get the people back.

BD: Is it your decision to hold the curtain

if the audience is not back, or do you start on time no matter what?

Moores: It’s our decision as to whether

the house curtain goes out, but usually we’d be advised to by a front-of-house

staff member. Sometimes we can’t wait. We just have to start

on time.

Coleman: Our audiences are used to us

starting on time, and we don’t want to change that.

Moores: They’re very well trained. The

first start absolutely is always on time, and I’m so glad that people

are here.

Coleman: Everybody comes on time because

they know they’re not going to be able to get in if they’re

late.

Moores: Because it’s at

the very back of the orchestra level in the auditorium, the person running

the lightboard is often very aware of people not being back. [Location

of the light-booth is shown in the wide photo above.] So he’ll

say that there’s still a long line, and if we can wait, we will.

BD: Do you get involved at all with the

actual positioning of lights, or is that just the lighting designer’s

domain?

Moores: It’s the

lighting designer and the director who say what they need.

BD: The stage director moves the people

on the stage, so you’re another level off from all of that?

Moores: We facilitate. In the rehearsal

process, the stage manager is the person who ensures that the people

doing the creating have what they need to create. Then in the

performance, the stage manager is the person who makes sure all those

things that have been created, happen on time. But we don’t really

have any artistic say-so. We could move a light cue slightly so

that it’s timed better, but we really do not have the authority to change

something that a director or a designer has set.

Coleman: We’re there to create an environment

where everybody can do their best work, whatever that environment

is. You’re dealing with a diverse group of people, and some powerful

personalities, and so what works for one group doesn’t work for another.

That’s where the real art in our profession comes. You’re

trying to create a situation where these people can do their best work

possible. In rehearsal, that environment may be where everybody

whispers all day, or where everybody shouts and screams at each other

all day. Our major contribution is developing trust with everybody,

so that they trust us, and they feel comfortable that they can do their

work.

BD: Do you know in advance that opera number

three is going to be quite different than opera number four?

Moores: Oh, yes.

BD: Does that influence who gets which

opera between the two of you?

Moores: A little bit. John is very

good at managing new and complicated productions. He’s excellent

at that, so he often does the newer productions. There are directors

and conductors that each one of us may have a rapport with, so for instance,

I’ll work with Mark Elder,

and John is working with John Copley this year

on La Gioconda. We choose by a mixture of items.

Coleman: Then there are shows that we

don’t want to do! [Both laugh]

Moores: Yes, so then I pull rank! [More

laughter]

Coleman: So, we look at the list and say

we’d like to do this show or that show, but I’d really rather not do

another one.

Moores: Or, I’ve done The Marriage

of Figaro five times, so I don’t want to do another one. Or

I’ve done it, so I may as well do it again.

BD: Is it better to keep the same team again

when the production comes back?

Moores: Again, it depends.

Coleman: It depends on the schedule, and

how things fall in the season. If two of them are back-to-back,

it would be impossible to do them both...

Moores: ...because often there are two productions

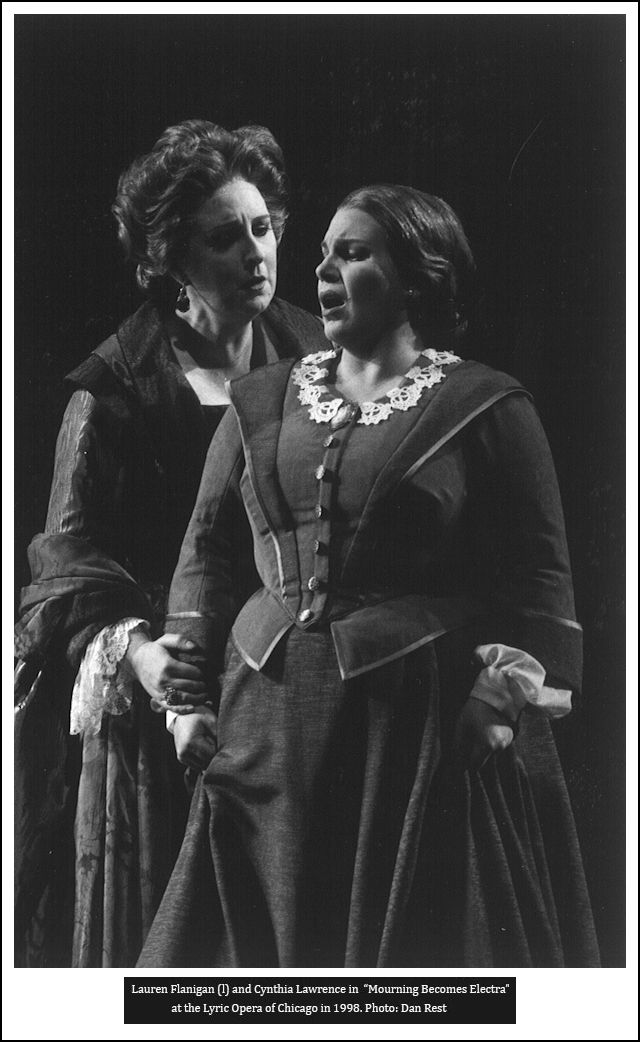

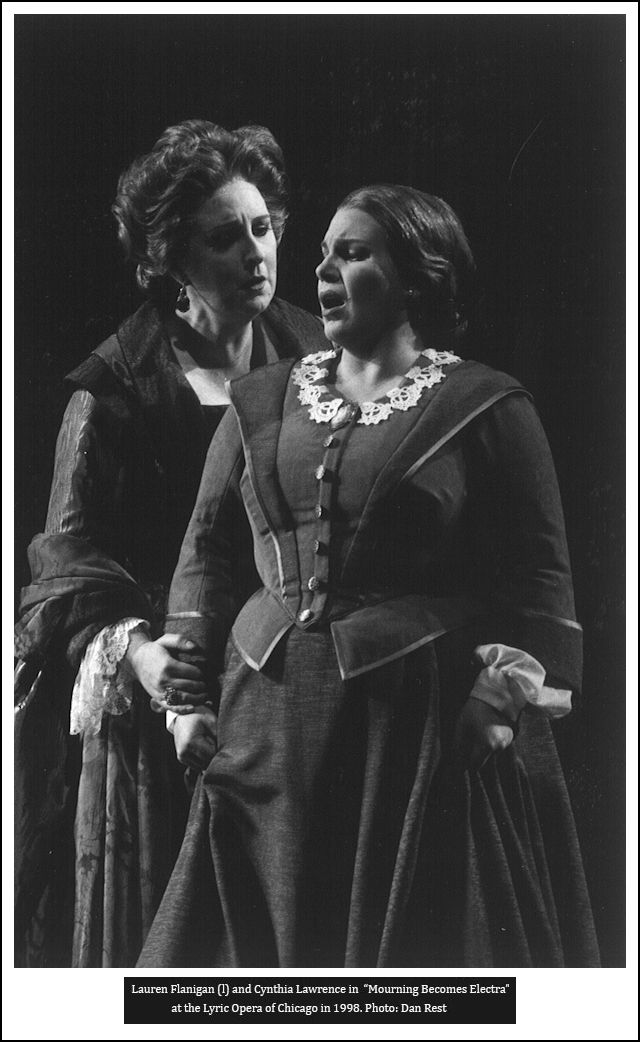

rehearsing at once. For example, La Gioconda and Mourning

Becomes Electra [Marvin

David Levy, shown below-left] are rehearsing at the same time,

so a stage manager can’t do both of them.

* * *

* *

BD: How long have you been with Lyric? [Remember,

this interview was held in 1998.]

Moores: I’ve been here since the 1994/95 season.

BD: So, you’re a relative new comer!

Moores: I’m very new compared to most

of the people, like John, for example.

Coleman: This is my ninth season, so I’ve

been here since the 1991 season.

BD: I assume that you want to be here

for a long time?

Moores: I do, yes.

Coleman: It’s a good place to be.

Moores: For the profession of opera stage

managing, this is really one of the best places to be.

Coleman: You don’t have to travel for

thirty weeks a year.

Moores: The length of the season is

pleasant. All of us have been quite itinerant, and have freelanced

around the country. You work five weeks here and six weeks there,

and two months in another place, and it’s nice to be able to stay in

one place for a whole season.

BD: What do you do with the other twenty

weeks?

Moores: Because of my position here as Production

Stage Manager, I have eight extra weeks. I work four weeks before

the season starts and four weeks after, and the rest of the time I enjoy

going back to England and spending the time with my family there.

BD: You don’t do other shows then?

Moores: I don’t, no.

BD: That’s quite

a luxury.

Moores: It’s lovely, it’s absolutely lovely!

[Laughs] It’s nice to have a block of time to go back to England.

BD: [To Coleman] What do you do

with the other twenty weeks?

Coleman: I’m crazy, and I usually do some

more stage managing.

Moores: John never rests.

BD: Do you seek out opera, or do you seek

out non-opera?

Coleman: It depends. I did five years

in Saint Louis, and then I also did Ballet Chicago a couple of years

ago. Because we had a baby, last year I did Chicago Opera Theater,

which was also kind of fun to do. So I’m trying now just to

be here, but I think there’s going to be a day again when I want to

run around again. It’s also nice to work for other companies, because

it gives you a different perspective. You realize the things which

are great about Lyric when you come back, and also by the end of the Lyric

season, you’re ready to work somewhere else for a while. [After

being with Lyric Opera for 30 years, Coleman went to the Metropolitan Opera

in 2021.]

Moores: It sets it in perspective.

BD: Can you bring good ideas back to Lyric?

Moores: Absolutely.

Coleman: Right.

Moores: One thing I miss about not

working elsewhere is that I don’t work with singers on the regional

circuit. It’s interesting to know who’s out there, and who might

be at Lyric in ten years.

BD: Lyric only gets them when they’re

fully formed.

Moores: Exactly. It’s nice to see

them earlier, and catch them earlier, as it were.

BD: Working with the Opera School [then

called the Lyric Opera Center for American Artists] doesn’t help that

at all?

Moores: It does, but we only work with them when

they are part of the main stage production. So it’s a little

different than working with a whole group of younger singers.

Coleman: There’s eleven, and there’s five new

ones every year. So it’s five new singers that you’re exposed to

who are young artists, as opposed to some place like Santa Fe or Saint

Louis, where there are twenty to forty new people that you would run

into, plus the principals.

BD: If someone wakes up some morning

and says they want to stage manage an opera, what do they do?

Coleman: [Laughs] They should go

to their doctor...

Moores: ...and think twice, yes.

[Much laughter] It’s interesting. In this country, there’s

not really a place to train in opera stage managing. A couple

of schools probably teach it, or have some courses. It’s might be

theater stage managing that’s taught in a university, and usually that’s

the only way to really get into opera stage managing.

BD: [Presenting a bright idea] Why

don’t you set up the Moores-Coleman School of Stage Managing? [Photo

at right shows Moores at her post backstage at Lyric Opera of Chicago.]

Moores: In all our spare time, yes! [Much

laughter] We’ve actually talked about that. I especially

like setting people on the road to stage manage, and because of my position

here, I get a lot of resumés from people who want to stage manage.

My advice to them is to send their resumés to smaller companies

who either use interns, or have a Second Assistant Stage Manager who

they don’t expect to be very experienced, and maybe they’d be happy to

break somebody in. You would start as an Assistant Stage Manager,

and work your way through from the small companies to the bigger companies.

Coleman: Not a lot of people actually go in wanting

to be a stage manager. It’s something they discover. It’s

not necessarily something you have to have a degree to do, but if you’re

fortunate enough to go to a university and be a theater stage manager,

you should seek out as much experience as you can in all the aspects.

If they have dance department, you should go volunteer and stage

manage for the ballet. If they have a music department, go and see

if you can stage manage their opera. It’s good to work in different

types of the arts, because you get a great appreciation from the people who

create on stage. It’s especially beneficial to the opera because you

deal with all sorts of performers. You have the ballet, and you sometimes

have actors from the legitimate theater, and you have singers, so the

more experience outside of opera you have, it all contributes to a better

knowledge of stage managing opera.

Moores: Of course, you have to have a musical

background. You’re basing everything on a piano-vocal score, and

hearing music, so you’ve got to be very comfortable in the world of music.

Although it’s not necessarily vital that you have languages, it

certainly helps you if you understand Italian and German. Those

seem to be the two most important languages for us.

BD: Unless they’re swearing at you, and

then it’s better not to know what they’re saying.

Moores: No, it’s good to know when they’re

swearing at you!

Coleman: [Wistfully] Usually, though,

they can convey it without having to know the language... [Laughter]

Moores: Yes, you can catch the gist of

it, but it’s helpful actually to know right away what they’re saying

instead of relying on somebody else to translate. If they’re swearing

at you, the translator may want to protect your feelings and not translate

it. But no, I’ve never been in that situation. I’ve known

when somebody is upset and speaking Italian. I’ve known what they’ve

meant, mainly because of the body language. John and I are very

good mind-readers.

BD: You’re back to being a shrink again.

Moores: We’re good at body-language,

context, all those things.

Coleman: Maybe I’m a shrink-sociologist.

[Laughter]

BD: When you’re stage managing a show, do you

each have an assistant?

Coleman: There’s a group. We have

a corps of assistant stage managers. There are five or six,

including the person who does the surtitles. They rotate on

shows, so we work with the different team members.

BD: Can they take over if somehow you

get caught in traffic and are not just there?

Moores: That doesn’t happen. Stage

managers never get held up in traffic, and they never get ill.

BD: [With a wink] It’s part of your contract

that you never get ill?

Moores: It’s not part of our contract,

but it’s a very real part of our job. What happens often is that

if we have a free day, we’ll be sick on that free day, and if at the

end of the season, when things start to wind down and you have time to

be ill, then you’ll be ill. People often come down with flu-like

symptoms, or have a cold at the end of the season, because your body says

you’ve got time now to do this. It’s happened enough that I don’t

think I’m just imagining it.

BD: It’s the sustained concentration

that keeps you healthy.

Moores: We’re very responsible people, and there is

nothing that would stop us being in the house to call a show... except

John almost wasn’t there because his wife was threatening to have her

baby during a performance! [Much laughter] So, we did have a

contingency plan because for that, John would have gone, of course.

BD: That’s good. The shows start

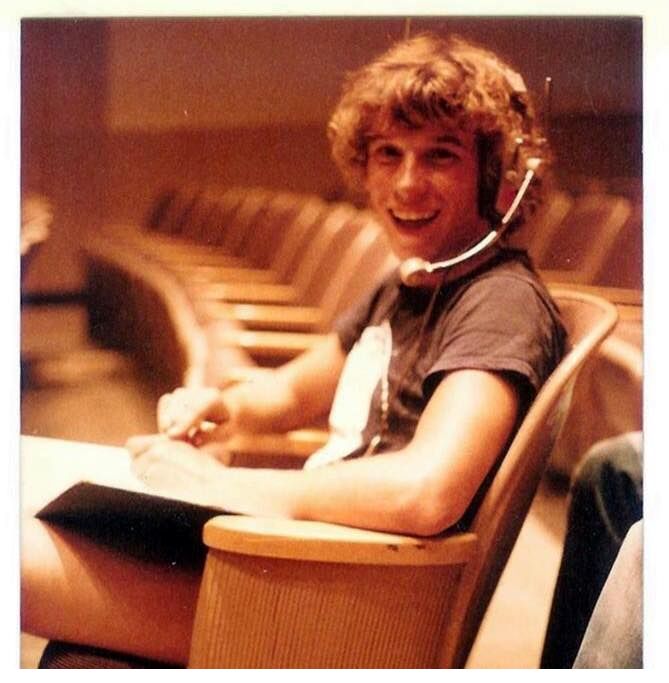

at 7:30 PM. What time are you in the house? [Photo at

right (from his Facebook page) shows Coleman in his younger days, learning

his craft at a different gig.]

Moores: We’re usually on stage at 7 PM,

if not before.

Coleman: It depends on the show really.

Usually, the later you get in the run, the later you’re in the house.

Moores: Sometimes the stage manager wants

to be around during the afternoon when the lighting is being focused,

or to make sure that the turntable is checked, or as Props finish their

pre-set, which often happens at four in the afternoon. We’re there

just to make sure that everything is the way it should be... not that

they don’t do their jobs, you understand, but it’s just a double-check.

We do a lot of double-checking.

Coleman: It also depends if the show has

something different, like there’s no curtain. You’d come in earlier

because you’d have to check that. If there’s a curtain, you can

come down and check that later. I always like to be in the building

about six o’clock on a 7:30 PM evening, just to find out if people are sick,

or if there’s anything you need to know about.

Moores: Anything untoward, yes.

Coleman: All this is if you don’t have

to be in the building for another rehearsal, which often you do on a performance

night when you’re doing something else.

Moores: Yes, often we’re working until

6 PM in another rehearsal for another production.

BD: Then you could grab a hamburger and

that’s it?

Coleman: Or a salad!

Moores: Actually, we’re all very good

cooks, so it’s not often hamburgers. That’s another stage managing

trait, to be a good cook.

BD: On a hot plate that’s back stage?

Coleman: Yes! [Much laughter]

Moores: [Defending the company’s

honor] No, it’s not that bad...

BD: In the end, is it all worth it?

Moores: Yes, oh, yes, yes, yes!

Coleman: It’s great. It’s a great

way to make a living. It’s work, but it’s not like working.

Moores: We feel sorry for people who don’t like

what they do. We don’t have a nine-to-five job, and sometimes

that irritates us because we don’t often have weekends off...

Coleman: ...or even just days off! [All

laugh]

Moores: Right, but we love what we do,

and it would be very hard to imagine having a job where we don’t care

passionately about what we do.

BD: That’s one of the common threads among

all of the people here in this building, as well as my own position!

Moores: I’m sure it is.

BD: Thank you for being with Lyric, and

running the thing so smoothly.

Moores: Oh, it’s our pleasure.

Coleman: Yes! Keep coming to see

the productions.

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded backstage at the Opera House in Chicago

on September 18, 1998. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following

month, and again

in January

of 1999. This transcription

was made in 2025, and posted on

this website at that time. My

thanks to British soprano

Una Barry

for her help in preparing this website

presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this

website, click here.

To read my thoughts

on editing these interviews for print,

as well as a few other interesting observations,

click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster

Bruce Duffie was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in

Chicago from 1975 until

its final moment as a classical

station in February of 2001.

His interviews have also appeared

in various magazines and journals since

1980, and he now continues his broadcast

series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited

to visit his website

for more information

about his work, including

selected transcripts of other

interviews, plus a full list

of his guests. He would also like

to call your attention to the photos

and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the

automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send

him E-Mail with

comments,

questions and suggestions.