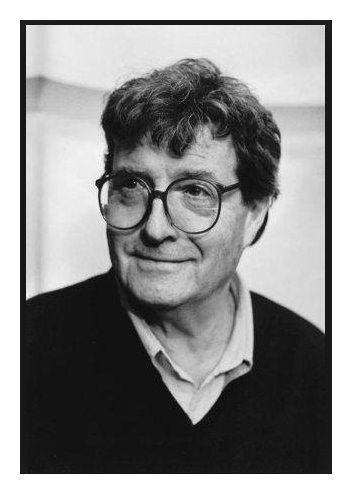

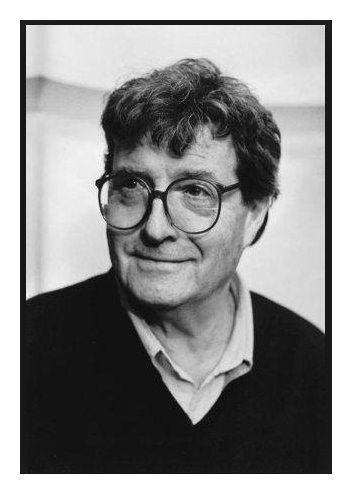

| For over forty years, the

British director John Copley has maintained a place as one of the

seminal theatrical figures of our time. Beginning with his debut

production of Suor Angelica

for Covent Garden in 1965, Mr. Copley became one of the most dominant

directorial influences in the history of British opera, staging some 15

productions at Covent Garden and 13 at the English National Opera, as

well as numerous productions in the English provinces. He has also

directed for every other major British and American company, as well as

those of Germany, Canada, Greece and Australia. Across a body of work

that has inspired a generation of opera goers, he has become known for

an approach emphasizing integrity to the truth of the score itself, as

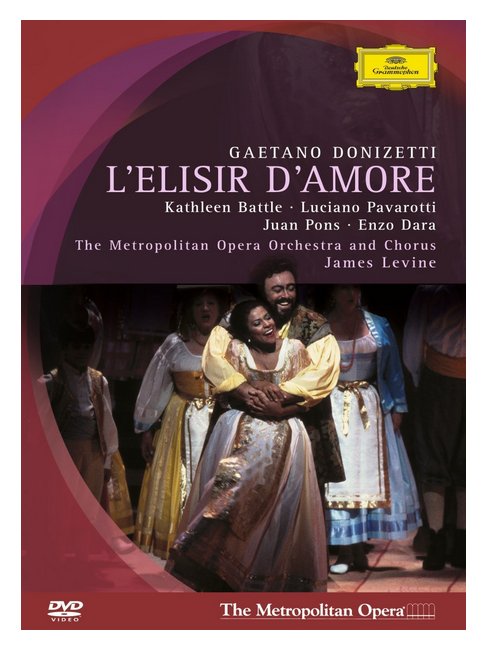

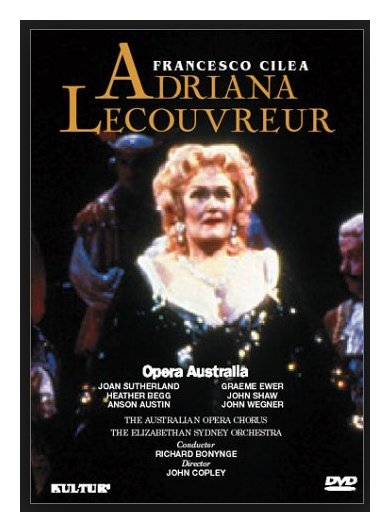

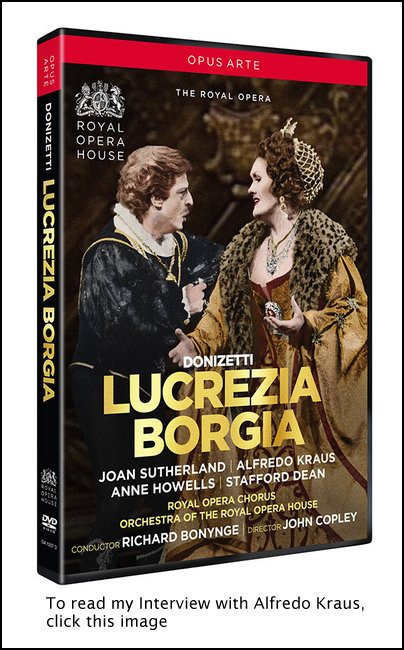

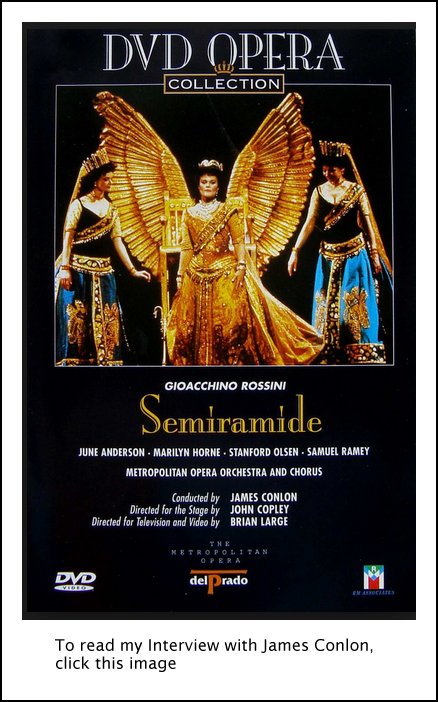

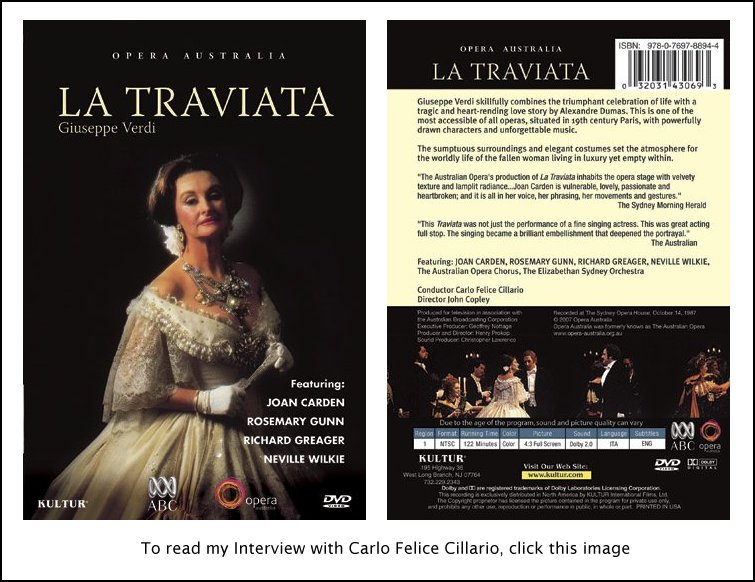

well as a boldly original sensibility. Born in Birmingham, he was a dancer at London’s Royal Ballet, and was active throughout his youth as an actor and designer. This all-inclusive immersion in the theatrical experience profoundly informed his work when he turned to his childhood love of opera. He began his career stage-managing for Sadler’s Wells Opera and Ballet and Covent Garden. Rising quickly through the ranks at Covent Garden, he became assistant producer and then principal resident producer of the company, and his interpretations of the Mozart-Da Ponte operas, the nineteenth-century Italian classics, and the works of Benjamin Britten became mainstays at Covent Garden and beyond. His productions proved to have evergreen appeal: his rendering of Le nozze di Figaro remained in the repertoire for 21 years, and his Così fan Tutte for 24. His production of La bohème is still in repertoire at the house, where it has played for 27 years. Over the span of his career at Covent Garden, he developed fruitful collaborations with conductors including Sir Georg Solti, Sir Colin Davis, Carlos Kleiber and Sir John Pritchard. At the English National Opera, he created landmark productions in partnership with artists such as Sir Charles Mackerras and Dame Janet Baker. Among these was Giulio Cesare, an uncommonly dynamic and theatrically charged staging of the Handel classic that decisively influenced subsequent directors of Baroque opera. Widely acclaimed, the production went on to San Francisco, Geneva and finally the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. His career in America is equally distinguished. Among his many milestone productions are a broodingly Romantic staging of Bellini’s Il pirata at the Metropolitan Opera in 2002, a fanciful Il barbiere di Siviglia seen in Chicago, San Francisco, Dallas and elsewhere, and a visually stunning rendering of Michael Tippett’s Midsummer Marriage for San Francisco Opera. Other recent work has included La Traviata in San Francisco in 2004, a new Norma at the Met in 2001, and a production of Madama Butterfly that opened the Santa Fe Opera’s new theater in 1998. In the 2005-2006 season he directed Carmen at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, Handel’s Rodelinda in Dallas, and Le nozze di Figaro at San Francisco Opera. 2006- 2007 produced Le nozze di Figaro with Boston Lyric Opera and Giulio Cesare at the Metropolitan Opera. Last season his work was seen at Lyric Opera of Chicago (Il barbiere di Siviglia) and the San Francisco Opera (Ariodante). His extraordinary productivity in Australia has yielded more than twenty-five productions for both the Australian Opera in Sydney and the Victorian State Opera in Melbourne. In Europe, he has an enduring relationship with the Greek National Opera, where he has staged Madama Butterfly, Otello, and Macbeth, as well as a new production of Il Corsaro in 2001. He has also helmed productions in Munich, Berlin, Geneva, Brussels, Amsterdam, Drottningholm, Stockholm and Gothenburg. In the current season, he directs Madama Butterfly for The Dallas Opera. Recently, he directed Idomeneo for the San Fancisco Opera, Le nozze di Figaro for Dallas Opera, and Peter Grimes in San Diego. Many of his productions can be seen on video, including Mary Stuart and his celebrated Giulio Cesare from English National Opera, as well as La bohème and Lucrezia Borgia from Covent Garden and L’elisir d’amore from the Metropolitan Opera. -- From the CAMI (Columbia

Artists Management Inc) website

-- Names which are links (in this box and below) refer to my Inteviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

John Copley at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1975 - Lucia with Sutherland,

Pavarotti, Saccomani, Ferrin; Bonynge,

Bardon, Weschler

1983 - La Bohème with Cotrubas, Ciannella, Raftery, Hong, Galbraith, Tajo; Navarro, Pizzi. Schuler (and all further productions unless noted) 1986-87 (Fall & Winter dates) - La Bohème with Ricciarelli/Daniels/Esperian, Polozov/Araiza/Shicoff/Hadley/Leech, Corbelli/Wroblewski, Daniels/Brown/Putnam, Washington, Capecchi; Mauceri/Thomas, Pizzi Orlando with Horne, Rolandi, Anderson, Gall; Mackerras, Pascoe, Tallchief 1988-89 - Tancredi with Horne, Cuberli, Merritt, Cox, Sharon Graham; Bartoletti, Conklin 1989-90 - Barber of Seville with Von Stade, Lopardo, Allen, Ghiuselev, Desderi; Pinzauti, Conklin 1994-95 (Fall & Winter Dates) - Barber of Seville with Von Stade/Mentzer/McCormick, Blake, Allen/Gilfrey/Braun, Ghiaurov/Halfvarson/Hogan, Desderi; Behr/Rizzi, Conklin 1997-98 - Peter Grimes with Heppner, Magee, Ellis, Nolen; Elder, Toms, Binder Idomeneo with Domingo/Cole, Devia, Vaness/Lawrence, Kasarova, Drews, Aceto; Nelson, Conklin 1998-99 (Opening Night) - Gioconda with Eaglen, Botha, Putilin, Redmon/Matos, Halfvarson, Maultsby; Bartoletti, Brown, Tallchief 1999-00 - Fledermaus with Lott, Evans, Bottone, Allen, Castle, Nolen, Del Carlo; Hager, Santicchi, Tallchief Carmen with Graves, Leech, Doss, Watson/Izzo, McCrorey, Cangelosi; Levi, Don, Tallchief 2000-01 (January & March dates) - Tosca with Dessi/Valayre, Giordani/Amiliato/LaScola, Raimondi/Lafont, Travis, Cangelosi; Bartoletti, Walton Barber of Seville with Kasarova/Bayrakdarian, Blake, Croft, Doss/Aceto, Del Carlo; Abel, Conklin, Binder 2003-04 - Lucia with Dessay, Álvarez/Ramsay, Holland, Tomasson, Cangelosi; López-Cobos, Bardon 2005-06 (Opening Night) (Fall and Winter Dates) - Carmen with Graves/Vizin, Thomsen/Shicoff/LaScola, D'Arcangelo/Doss, Rost/Racette, Van Horn; Davis, Don 2007-08 - Barber of Seville with DiDonato, Osborn/Maut, Gunn/Dothard, Tigges, Kraus/Shore; Renzetti, Conklin |

JC: Yes, but they’re

very economical. Bohème

is a masterpiece. You

cannot go wrong on Bohème.

You could do it any way. You can do it with grown up people, you

can do it with young

people, you can do it in the 1830s, you can do it

in 1920, you can do anything. You can’t wreck it. It’s just

the perfect

piece. Butterfly is a

perfect piece, too.

JC: Yes, but they’re

very economical. Bohème

is a masterpiece. You

cannot go wrong on Bohème.

You could do it any way. You can do it with grown up people, you

can do it with young

people, you can do it in the 1830s, you can do it

in 1920, you can do anything. You can’t wreck it. It’s just

the perfect

piece. Butterfly is a

perfect piece, too. BD: With the sides and

back of the scenery?

BD: With the sides and

back of the scenery?

JC: Oh not if they’re

playing Mimì, no. [Both laugh] Too thin? Nice

and tall and healthy is more of what we want. I like to see

people looking like the

people they’re supposed to be. I hardly

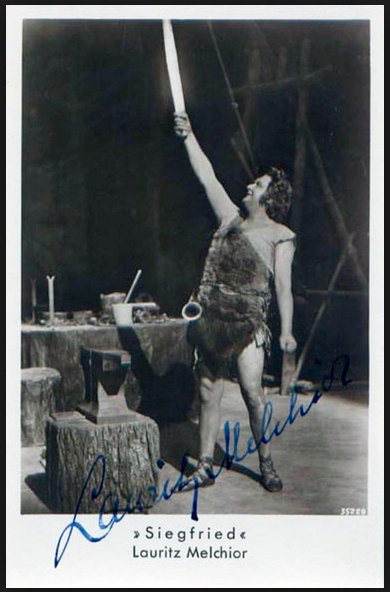

see a Wagner cast come on who look like they’re supposed to

look. When do you see Sieglinde and Siegmund looking like young

forest people? When I

saw Peter Hoffmann a few years ago, that

was why he was so sensational. Suddenly there was a

Parsifal who looked like Parsifal! There was a Siegmund who

looked like Siegmund.

JC: Oh not if they’re

playing Mimì, no. [Both laugh] Too thin? Nice

and tall and healthy is more of what we want. I like to see

people looking like the

people they’re supposed to be. I hardly

see a Wagner cast come on who look like they’re supposed to

look. When do you see Sieglinde and Siegmund looking like young

forest people? When I

saw Peter Hoffmann a few years ago, that

was why he was so sensational. Suddenly there was a

Parsifal who looked like Parsifal! There was a Siegmund who

looked like Siegmund.| The Guilty Mother (French: La Mère coupable) subtitled The Other Tartuffe is the third

play of the Figaro trilogy by

Pierre Beaumarchais; its predecessors were The Barber of Seville and The Marriage of Figaro. This was

the author's last play. It is rarely revived. Like the earlier plays of

the trilogy it has been turned into operatic form, but it has not

entered the general opera repertoire. The action takes place twenty years after the previous play in the trilogy, The Marriage of Figaro. The story's premise is that several years ago, while the Count was away on a long business trip, the Countess and Chérubin spent a night together. When the Countess told Chérubin that what they did was wrong and that she could never see him again, he went away to war and intentionally let himself be mortally wounded on the field. As he lay dying, he wrote a final letter to the Countess, declaring his love and regrets, and making mention of all the things they had done. The Countess did not have the heart to throw away the letter, and instead had a special box supplied by an Irishman called Bégearss, with a secret compartment in which to store the incriminating note, so the Count would never find it. Soon after, to her dismay, the Countess discovered herself pregnant with Chérubin's child. The Count has been suspicious all these years that he is not the father of Léon, the Countess's son, and so he has been rapidly trying to spend his fortune to ensure the boy won't inherit any of it, even having gone so far as to renounce his title and move the family to Paris; but he has nevertheless held some doubts, and therefore has never officially disowned the boy or even brought up his suspicions to the Countess. Meanwhile, the Count has an illegitimate child of his own, a daughter named Florestine. Bégearss wants to marry her, and to ensure that she will be the Count's only heir, he begins to stir up trouble over the Countess's secret. Figaro and Suzanne, who are still married, must once again come to the rescue of the Count and Countess; and of their illegitimate children Léon and Florestine, who are secretly in love with each other. The first proposal to turn the The Guilty Mother into an opera was by André Grétry, but the project came to nothing. Darius Milhaud's La mère coupable (1966) was the first to be completed, and Inger Wikström made an adaptation called Den Brottsliga Modern. In John Corigliano's The Ghosts of Versailles, there is a subplot in which the ghost of Beaumarchais, as an entertainment for the ghost of Marie Antoinette (with whom he is in love), conjures up a performance of the play as an opera: A Figaro for Antonia, claiming that by doing so he will change history and that Marie Antoinette will not be executed. In April 2010, the opera L'amour coupable by Thierry Pécou to a libretto by Eugène Green based on the Beaumarchais play, received its world premiere at L'Opéra de Rouen. *

* *

* *

Chérubin is an opera (comédie chantée) in three acts by Jules Massenet to a French libretto by Francis de Croisset and Henri Cain after de Croisset's play of the same name. It was first performed at the Opéra de Monte-Carlo on 14 February 1905, with Mary Garden in the title role. The story is a light-hearted addition to Beaumarchais' Figaro plays, the action taking place soon after that of The Marriage of Figaro, and imagines festivities in celebration of Chérubin's first military commission and seventeenth birthday. A farcical romp ensues, brought on by Chérubin lusting after each of the female characters and inspiring general confusion. |

JC: Sure, but the thing

is in something like

Tancredi, she is the center

of it. Remember what I was saying earlier, that I don’t just plan

everything. I like to do it with the people and what they

bring. It’s a cumulative business. They actually move you

into

another area. They stimulate many, many things. You

suddenly

find that they’re on a part of the stage that you would not imagine

they would be, and it’s all growing, and then you build on that and

move

somewhere else, and that’s how the whole process works. But if

you only have your leading lady for a day and a half, it’s quite tricky.

JC: Sure, but the thing

is in something like

Tancredi, she is the center

of it. Remember what I was saying earlier, that I don’t just plan

everything. I like to do it with the people and what they

bring. It’s a cumulative business. They actually move you

into

another area. They stimulate many, many things. You

suddenly

find that they’re on a part of the stage that you would not imagine

they would be, and it’s all growing, and then you build on that and

move

somewhere else, and that’s how the whole process works. But if

you only have your leading lady for a day and a half, it’s quite tricky. JC: No. I don’t

think the orchestra was as loud. With Erich Kleiber and people

like that, I don’t think

the orchestra was as loud as it is now. With the

recordings and the conductors who have this high-tech precision with a

great sheen and great polish on the strings, actually,

in terms of decibels, I think it’s louder.

JC: No. I don’t

think the orchestra was as loud. With Erich Kleiber and people

like that, I don’t think

the orchestra was as loud as it is now. With the

recordings and the conductors who have this high-tech precision with a

great sheen and great polish on the strings, actually,

in terms of decibels, I think it’s louder. BD: Is there ever a

chance that one of those doors

will open on the second or third or fourth performance?

BD: Is there ever a

chance that one of those doors

will open on the second or third or fourth performance?  JC: Oh, they come every

day! [Laughs]

I don’t know what to tell them. Opera’s in such transition.

I don’t think that opera in ten years is going to be anything

like it is now.

JC: Oh, they come every

day! [Laughs]

I don’t know what to tell them. Opera’s in such transition.

I don’t think that opera in ten years is going to be anything

like it is now.| Massenet’s Don Quichotte

is a gentle old opera in the sentimental French tradition, a work

perhaps easier to love than to admire. Masterly in a minor way, it can

work its wiles only when a bass of great authority appears, falls in

love with the title role and persuades a company to let him sing it.

That is exactly why the New York City Opera's new production of Don Quichotte

,

which had its premiere Friday night, turned out to be a notable event.

Mr. Ramey, as sweetly befuddled an old chevalier as ever tilted at a

windmill, immediately took control of the stage, and finally of the

audience's heart, in a performance that for once justified opera’s

often-abused star system. Robin Don’s economical sets, inspired by Gustave Dore’s familiar Don Quixote etchings, were ingenious in concept, but they sometimes constricted action owing to their vertiginous tilt. Cutout horses representing Rosinante and Sancho’s mule provided a funny moment or two. Having the flat simulated etchings open out to give three-dimensional effects, like an old-fashioned valentine, helped to evoke a storybook atmosphere. The drab colors, dictated by the etching motif, made sense, but did become monotonous over the five-act span.  Don Quichotte lives or dies by its leading bass, but a fair share of applause for this production’s success must go to Mario Bernardi’s alert and pliant conducting and to an able supporting cast. John Copley’s staging, simple and uncluttered in the most crucial scenes, allowed for plenty of mock-Iberian bustle by chorus and dancers. -- From the review

in The New York Times by

Donal Henahan, August 3, 1986. (Text only - photo added from

another source.)

|

BD: Then why did you

decline the Chérubin?

BD: Then why did you

decline the Chérubin?| Chicago has the finest opera

company in America, Lyric Opera, and the foremost Rossini scholar in

the world, Philip

Gossett. What could be more natural than to bring together both

parties in the service of a worthy, if neglected, early opera by

Gioacchino Rossini? That is precisely what took place at the Civic

Opera House Saturday night, when Lyric Opera presented the Chicago

premiere of Rossini`s Tancredi,

in a new production based on the critical edition by Gossett. John Copley`s production, which Lyric is sharing with the Los Angeles Music Center Opera, proved more than just another quaint bel canto exhumation, but a notable addition to the ongoing international revival of the Italian composer`s stage rarities. The Lyric`s Bruno Bartoletti was in charge in the pit to assure that stage and pit spoke authentic Rossini. With an all-American roster of singers headed by the redoubtable Marilyn Horne giving voice to Rossini`s taxing flights of vocalism, Tancredi was treated as the work of serious art that it is. Tancredi (1813) was Rossini`s first important opera seria, and the first to fix his star in the international galaxy. The text derives from a tragedy by Voltaire, one that, even in its severely condensed adaptation by librettist Gaetano Rossi, spins a wildly improbable tangle of love, fidelity, duty and patriotism in 11th-Century Sicily. But the much-underrated score shows us that, even at the dewy age of 21, Rossini had the essentials of his mature style firmly in place. If the composer was more interested in probing poignant emotions (through the most florid vocal writing) than in placing his characters within plausible dramatic situations, that`s our problem, not his. Any modern revival must grapple honestly with the problem of how to remain faithful to the Rossinian essence in theater terms acceptable to an audience of the late 20th Century. This tricky juggling act Copley was able to bring off nicely, allowing for some clunky choral maneuvers. Although the play-within-a-play has become one of the hoariest cliches in opera, the director brought his own inventive twists to the conceit, focusing one`s attention on the heartfelt emotions that Rossini delineates through his music. John Conklin (set designer) and Michael Stennett (costumes) provided a handsome visual framework for the ``action,`` whose descending set pieces allowed for swift scene changes-a big plus in a work that needs all the movement it can get. Stennett`s bejeweled, richly textured costumes set an eye-filling array of gold, red and blue fabrics against the stark gray brick of the Syracuse battlements. -- From a review in the Chicago Tribune by John von Rhein,

January 16, 1989

|

JC: Not at the

moment. I’m not NOT coming; it’s just that we haven’t sorted

it out. [See the chart at the

top of this webpage for his appearances in Chicago, and links to my

interviews with many of his artists.] The next two years

are absolutely gone, but I’m being awfully cautious about ’91 and

’92. I’m

only at home seven weeks this year.

JC: Not at the

moment. I’m not NOT coming; it’s just that we haven’t sorted

it out. [See the chart at the

top of this webpage for his appearances in Chicago, and links to my

interviews with many of his artists.] The next two years

are absolutely gone, but I’m being awfully cautious about ’91 and

’92. I’m

only at home seven weeks this year.

© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 14, 1989. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following week, and again in 1993, 1997, and 1998. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.