HUGH PRUETT, LYRIC COSTUME CHIEFBy James Janega, Tribune Staff Writer CHICAGO TRIBUNE May 6, 2000

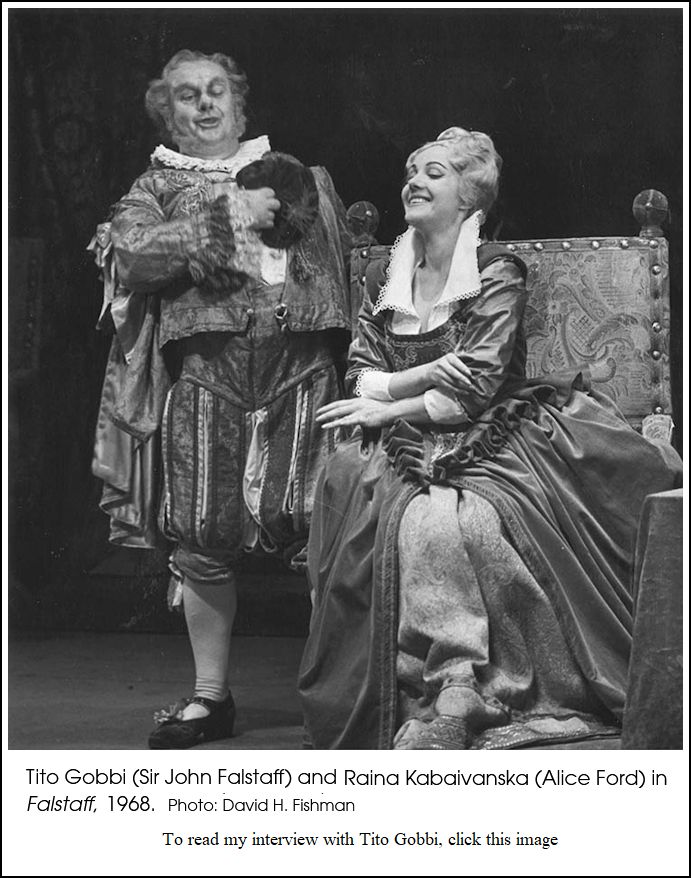

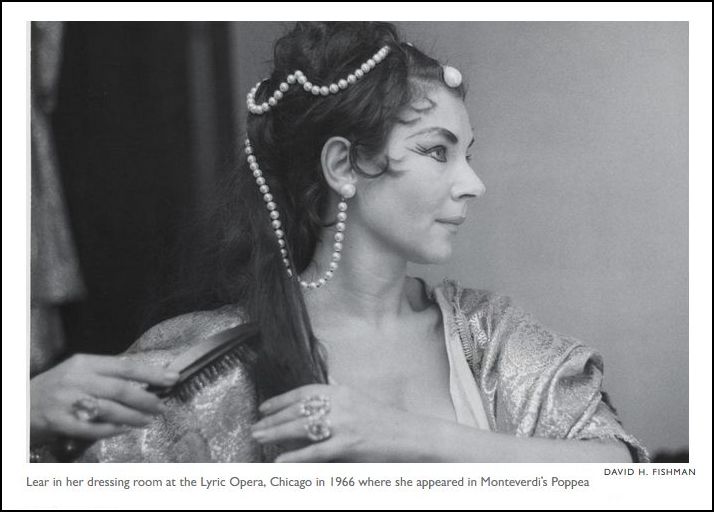

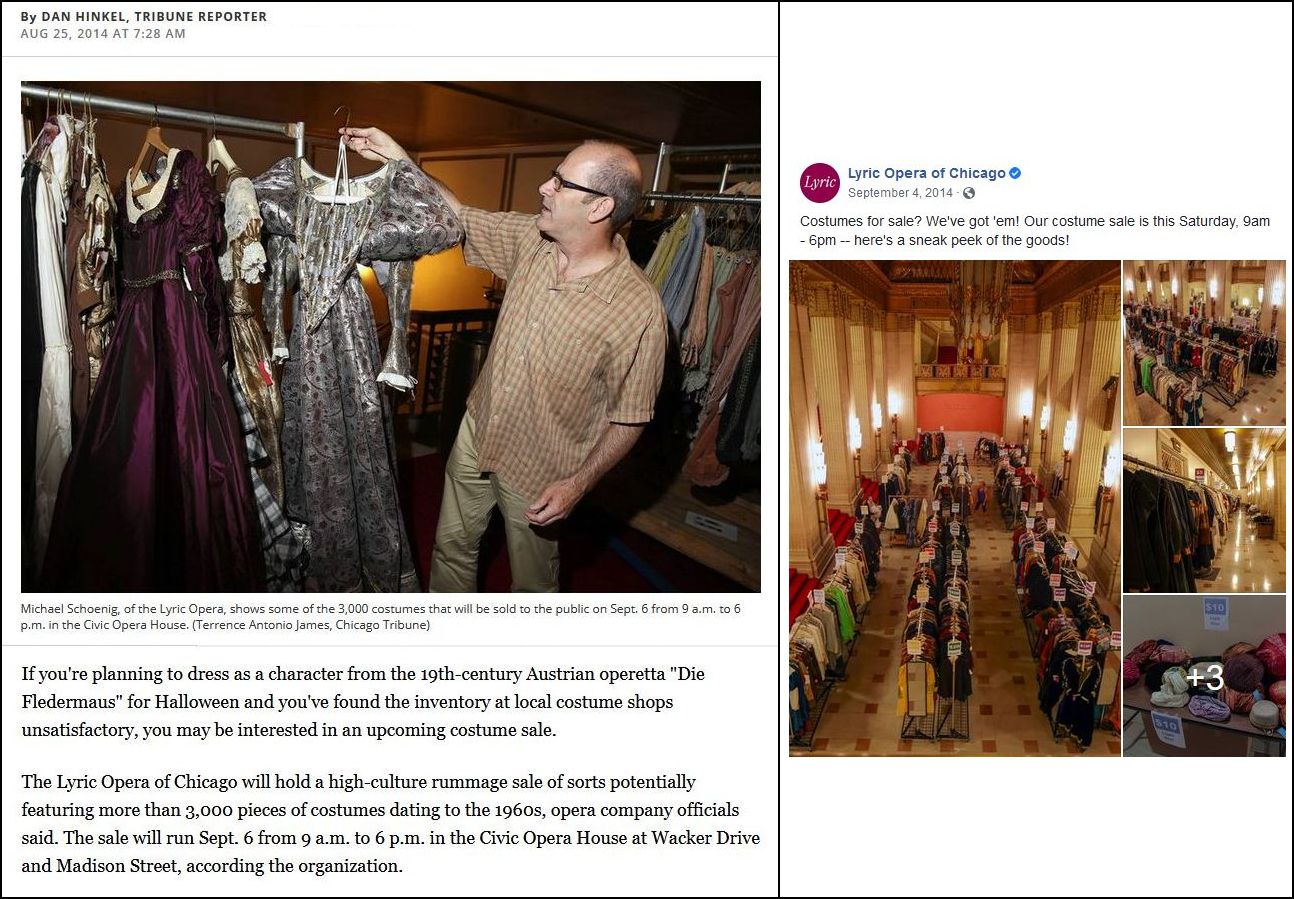

Hugh Pruett, 68, of Chicago, whose supervision of costume designs at the Lyric Opera of Chicago made Mefistofele more devilish, Violetta seem more doomed, and Sir John Falstaff more corpulent, died Friday, May 5, in Rush Presbyterian-St. Luke's Medical Center, of heart failure. "It was all very stylish," said John Copley, a frequent stage director at the Lyric Opera. "He had a very good eye for what was necessary, and he would always find you a few thousand dollars when it was needed, would pinch it from somewhere." For more than 40 years, Mr. Pruett worked backstage at the Lyric. He started as an assistant to the company's wardrobe master and after many years as a co-director, he became director of costumes in 1996. Under Mr. Pruett's direction, the Lyric costume staff created stunning designs for Verdi's "La Traviata," stout costumes for "Falstaff," whimsical creations for Boito's "Mefistofele," and clothing both modern and fanciful for any number of other productions. Yet before starting at the Lyric, Mr. Pruett had no formal experience in costume work. Born in Martin County, Indiana, Mr. Pruett attended Indiana University and graduated from Miami University of Ohio before earning a business degree from Harvard University. He joined the Navy, serving as an assistant to an admiral in Hawaii. It was a period highlighted by trips to Guam and Japan, and which segued into a position with a construction firm in Hawaii. It was while visiting friends in Chicago in 1959 that Mr. Pruett heard of an opening at the Lyric. He remained in the job for the rest of his life. Mr. Pruett came to Chicago already having a love of opera, having listened to 78 r.p.m. records of famed Italian tenor Enrico Caruso at his grandmother's knee in Indiana. His background was in business when he joined the Lyric, but his postion there did not require a degree in costume design. Over the years he acquired an exhaustive knowledge of historical costuming, costume making, and fabric purchasing, said Stan Dufford, retired wigmaster for the Lyric. Beyond that, added Dufford, Mr. Pruett also served as a diplomatic ombudsman for ill-fitted opera singers. In addition to his work at the Lyric, Mr. Pruett served since 1975 as business agent for the Chicago local of the wardrobe union, part of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employes, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts. He is survived by his mother, Agnes E. Smith. |

BD: You try to make the principal

artists look a little more spiffy?

BD: You try to make the principal

artists look a little more spiffy?

BD: Do you like being in the costume

business?

BD: Do you like being in the costume

business? BD: What is perhaps the most complicated

production you’ve had to do over 40 years?

BD: What is perhaps the most complicated

production you’ve had to do over 40 years? BD: Do you make everything

here, or do you go out and buy some things?

BD: Do you make everything

here, or do you go out and buy some things?

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded backstage at the Opera House in Chicago on September 3, 1998. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following November, and again in February of 1999. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.