|

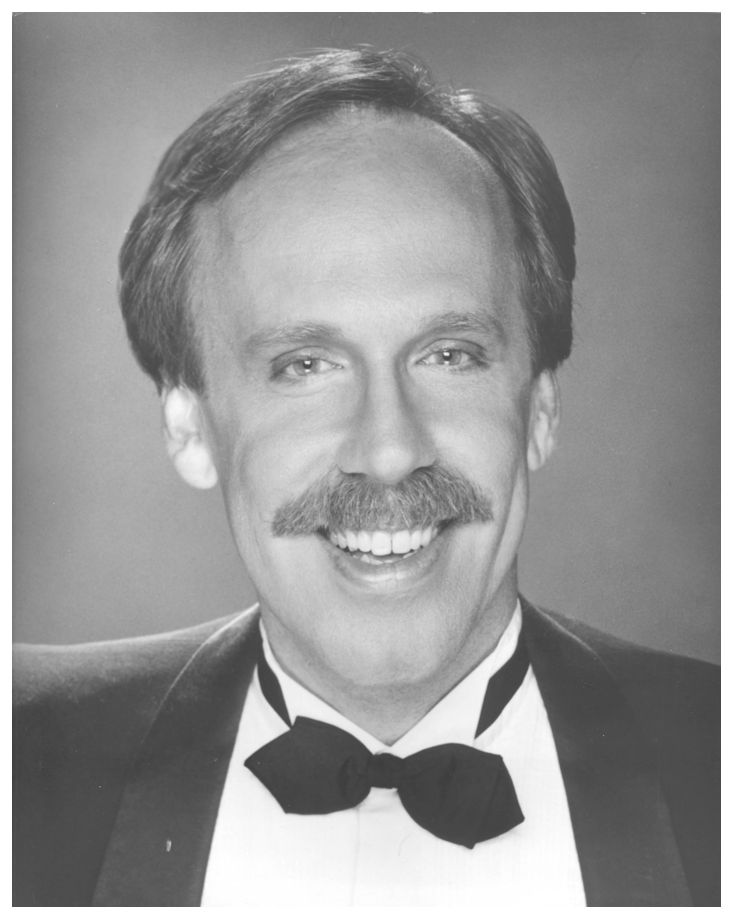

Baritone Robert Orth

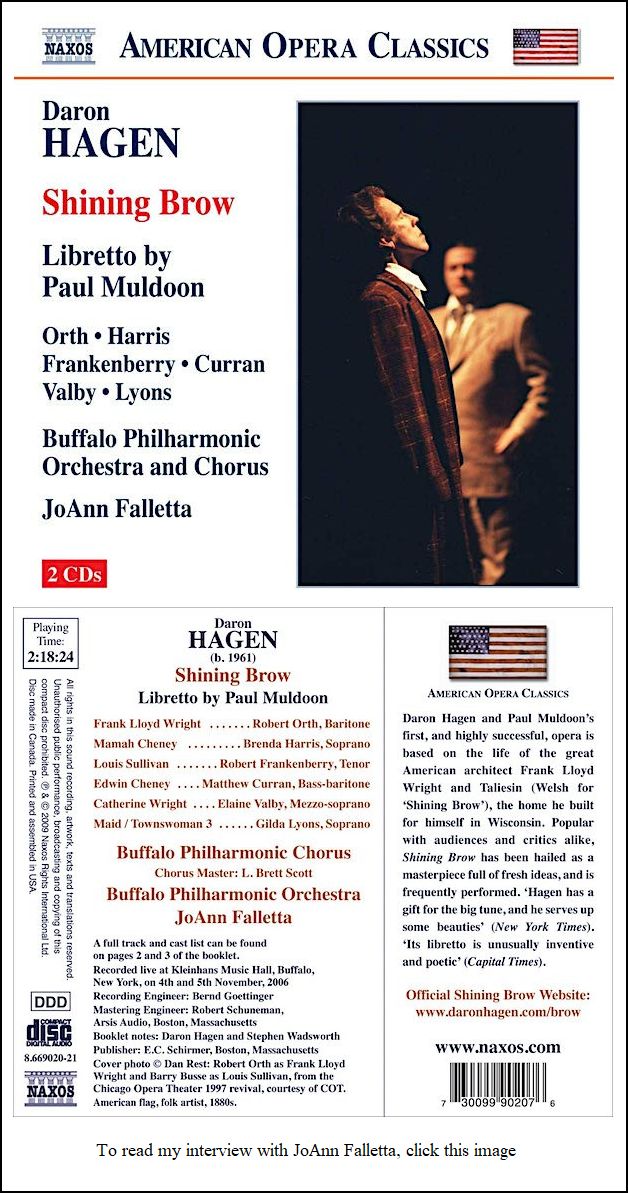

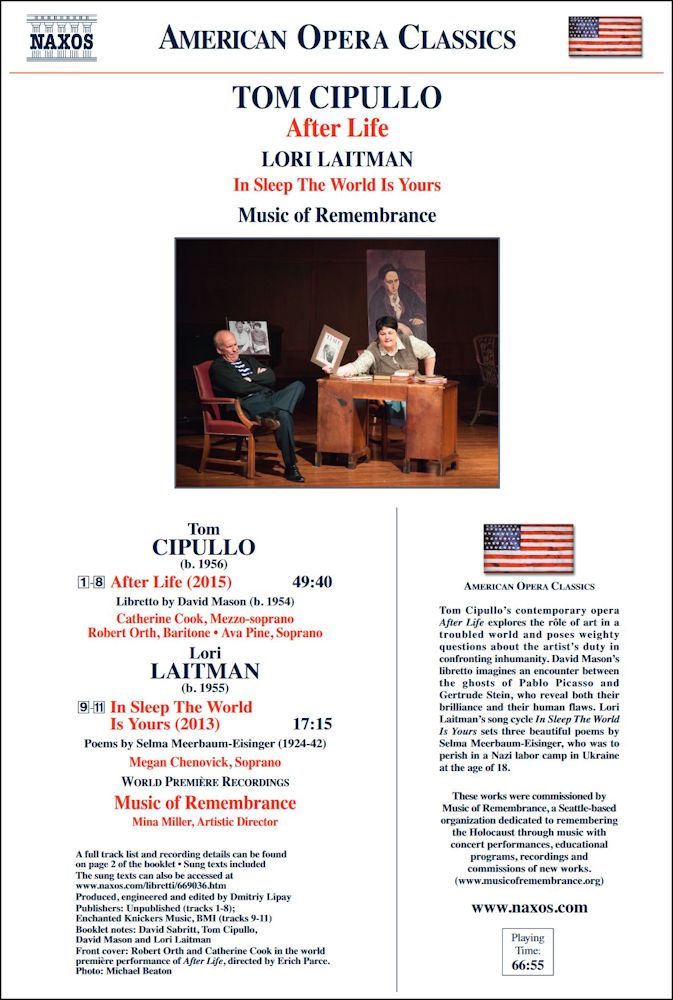

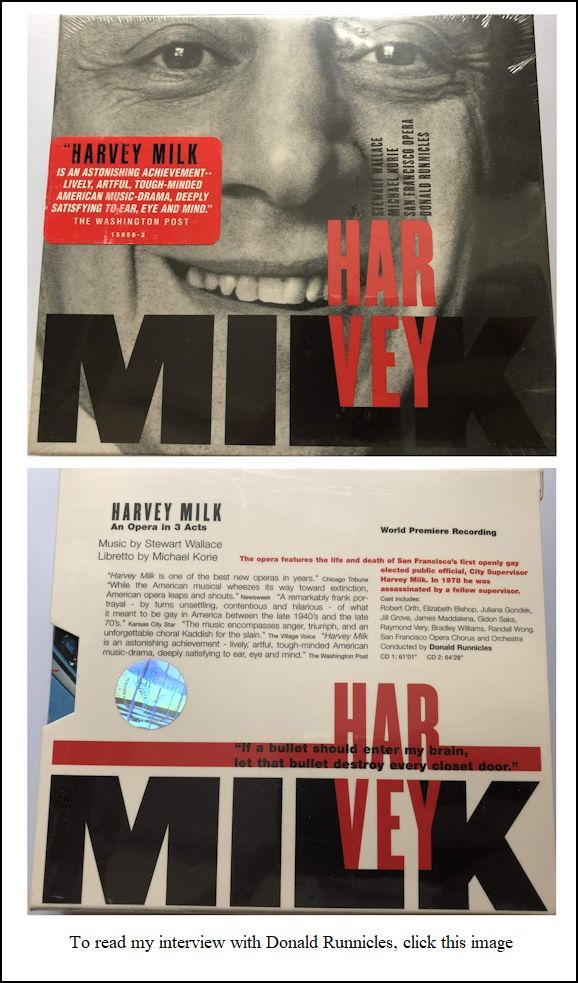

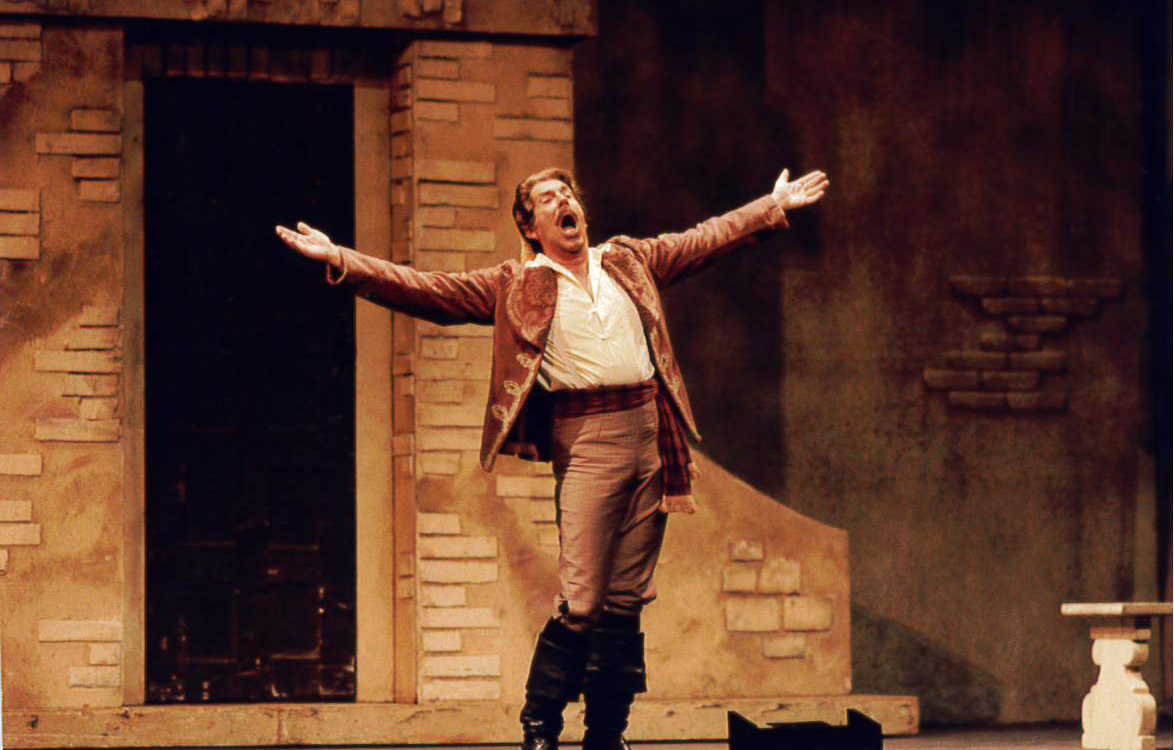

As for popular operatic repertoire, the baritone frequently appeared as Figaro in “The Barber of Seville,” Eisenstein in “Die Fledermaus,” Malatesta in “Don Pasquale,” Danilo in “The Merry Widow,” Germont in “La Traviata,” and Sharpless in “Madama Butterfly.” Additionally, Orth enjoyed musicals, appearing as Don

Quixote in “Man of La Mancha,” Billy Bigelow in “Carousel,” El Gallo in

“The Fantasticks,” Henry Higgins in “My Fair Lady,” and Fredrik in “A Little

Night Music.” Orth found joy in singing from a young age, participating in church and school choirs. Prior to pursuing a full-time singing career for himself in 1974, he taught music at public schools in his hometown of Chicago. Orth prided himself in being “the best baritone in his price

range,” as he puts it in his website biography, as well as a “devoted

family man.” He performed at esteemed opera houses across the U.S., and

appeared regularly with Central City Opera from 1983 – 2016. He was

named Artist of the Year by both the New York City Opera and Seattle

Opera. == Throughout this webpage, names which

are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

© 1997 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on July 4, 1997. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following week. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.