|

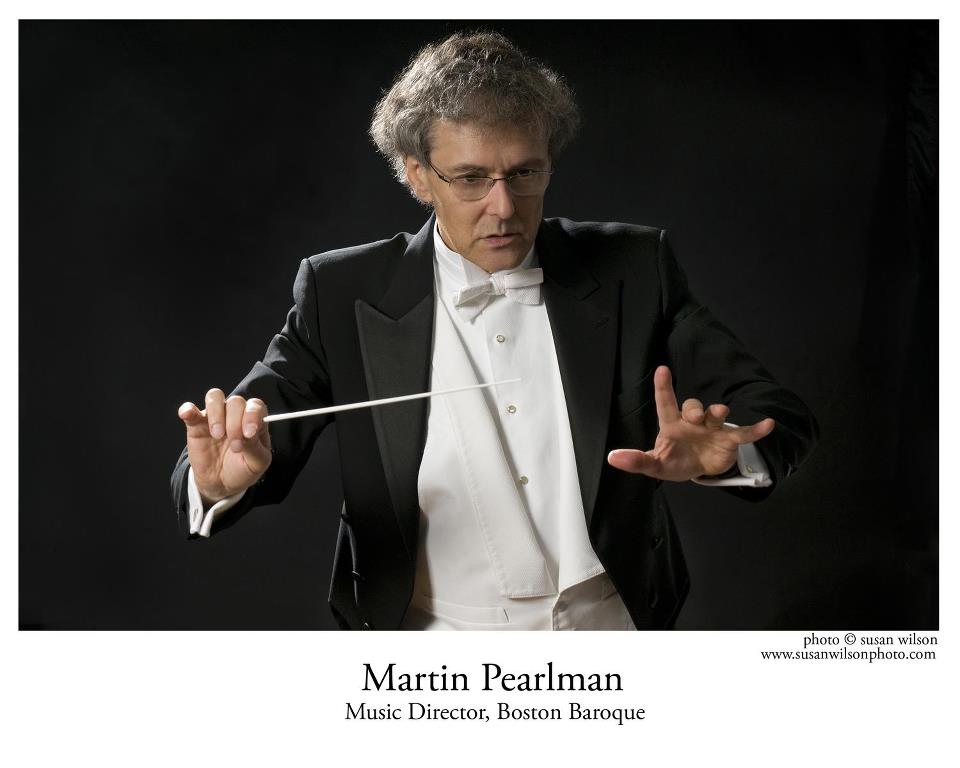

Born in Chicago, Illinois, May 21, 1945, Martin Pearlman received training in composition, violin, piano, and theory. He received a B.A. in 1967 from Cornell University, where he studied composition with Karel Husa and Robert Palmer and began studying harpsichord with Donald Paterson. After Cornell, Mr. Pearlman studied harpsichord with renowned harpsichordist and early music pioneer Gustav Leonhardt in Amsterdam on a Fulbright Grant (1967–68). In 1971, he received an M.M. in composition from Yale University, studying composition with Yehudi Wyner, working with noted harpsichordist Ralph Kirkpatrick, and working in the electronic music studio. In 1971, he moved to Boston, where he won the Erwin Bodky competition as a harpsichordist, and began performing widely in solo recitals and concertos. He also was a prizewinner at the Festival of Flanders competition in Bruges, Belgium.

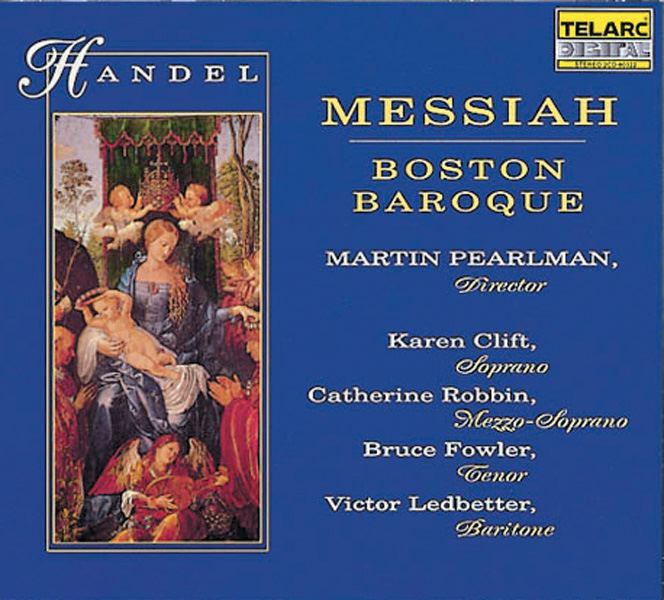

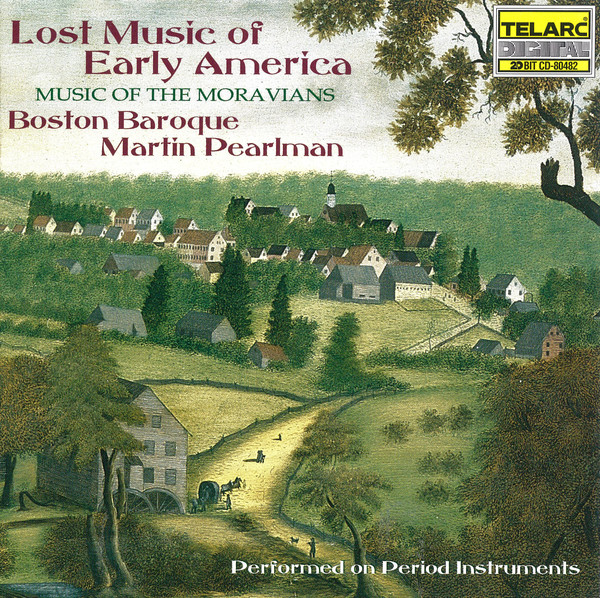

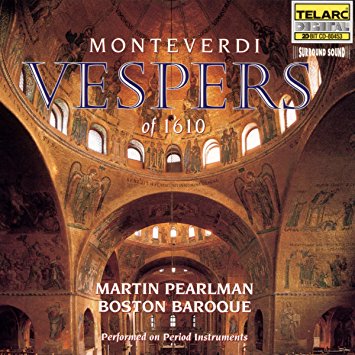

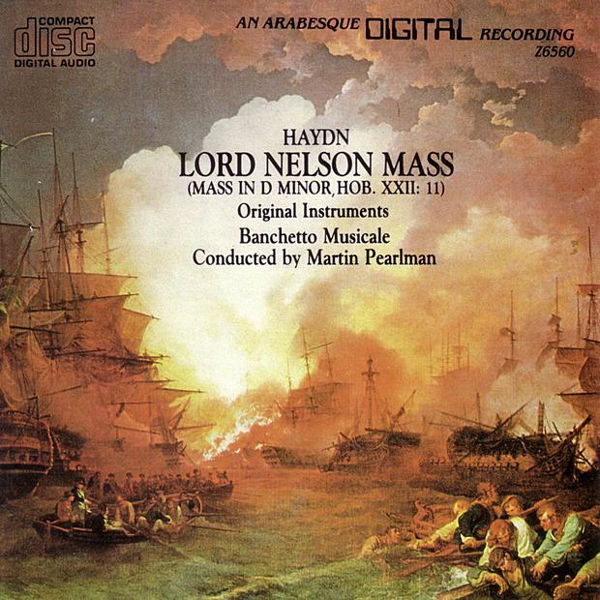

With modern-instrument ensembles, Pearlman made his Kennedy Center debut conducting The Washington Opera in Handel's Semele, led the National Arts Center Orchestra of Ottawa in the Monteverdi Vespers, and has conducted the Minnesota Orchestra, the Utah Opera, Opera Columbus, Boston Lyric Opera, San Antonio Symphony, the New World Symphony, Omaha Symphony, Alabama Symphony and others. Pearlman is the only conductor from the period-instrument field to have performed live on the internationally televised Grammy Awards show. [Recording shown at left is their fourth to be nominated for a Grammy] Although conducting is his main focus, Martin Pearlman is also a successful composer, an acclaimed harpsichordist, and respected scholar. Pearlman's work as a composer has been influenced by, among others, Carter, Boulez, and certain composers of the following generation. Recent compositions include his 3-act Finnegans Wake: an Operoar on texts by James Joyce; The Creation According to Orpheus for piano, harp and percussion soloists with string orchestra; Beethoven Fantasy on WoO77 for solo piano, and music for three Samuel Beckett plays (Words and Music, Cascando, ... but the clouds ...), commissioned by the 92nd Street Y in New York for the Beckett centennial in 2006, and produced there and at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Mr. Pearlman has also edited a new critical edition of Armand-Louis Couperin’s complete keyboard works, prepared new performing versions of Monteverdi's operas Il ritorno d'Ulisse and L'incoronazione di Poppea, and created a new orchestration and edition of Cimarosa's Il maestro di cappella. Since 2002, he has been a Professor of Music, Historical Performance at Boston University, College of Fine Arts, where he directs Baroque ensembles and teaches in the Historical Performance department of the School of Music. -- Names which are links refer to my Interviews

elsewhere on my website. BD

|

BD: Let me try to draw a very strange

parallel between this idea of the old or the very recent technology,

and the newest technology as being a little better. When we first

started again to use ‘original instruments’,

they sounded sort of scratchy and out of tune. Now we have learned

how to make the old instruments sound better. Is there any kind

of parallel there?

BD: Let me try to draw a very strange

parallel between this idea of the old or the very recent technology,

and the newest technology as being a little better. When we first

started again to use ‘original instruments’,

they sounded sort of scratchy and out of tune. Now we have learned

how to make the old instruments sound better. Is there any kind

of parallel there?  MP: Every performance is something

of the performer in any case. There are a few people who

claim they try and just let the music perform itself objectively

— which I think is kind of a questionable idea

— but even if one tried to do that, it’s all in one’s perception.

There’s no question that there’s something of the performer contained

within. But my own view is that when I approach a piece of music,

I try to look at the music and react to it in an emotional way.

All of it is shaped by my experience in life, which includes my experience

of studying baroque music. So that creates the framework in which

I can react.

MP: Every performance is something

of the performer in any case. There are a few people who

claim they try and just let the music perform itself objectively

— which I think is kind of a questionable idea

— but even if one tried to do that, it’s all in one’s perception.

There’s no question that there’s something of the performer contained

within. But my own view is that when I approach a piece of music,

I try to look at the music and react to it in an emotional way.

All of it is shaped by my experience in life, which includes my experience

of studying baroque music. So that creates the framework in which

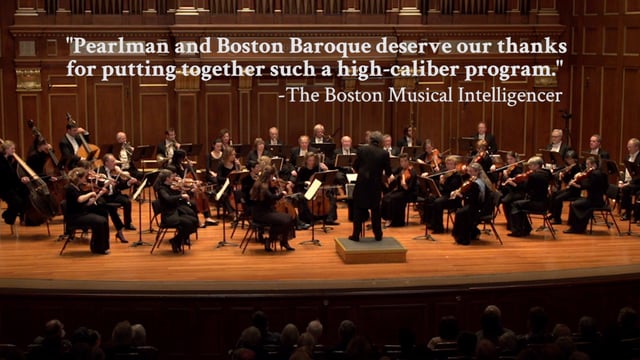

I can react.  MP: I enjoy doing both. My orchestra,

Boston Baroque, performs on period instruments, and we always have.

I sometimes perform with other symphony orchestras or opera companies

that use modern instruments. Sometimes it is even some of the same

music, and I enjoy doing that. It’s a different experience. I

don’t care to go into a modern orchestra and try to make them imitate

the sound of a baroque orchestra. Your ears are open, so you shape

it starting from what you have and what you hear. That way it doesn’t

become a cheap imitation of something else. It’s music-making in

its own right, and the same as if a pianist were to play Bach or some earlier

music that was written for the harpsichord. You don’t necessarily

want to just imitate a harpsichord sound on the modern piano. You

want to use the capacity of the piano as well because you can’t truly imitate

the harpsichord sound, or it comes out sounding like an imitation.

MP: I enjoy doing both. My orchestra,

Boston Baroque, performs on period instruments, and we always have.

I sometimes perform with other symphony orchestras or opera companies

that use modern instruments. Sometimes it is even some of the same

music, and I enjoy doing that. It’s a different experience. I

don’t care to go into a modern orchestra and try to make them imitate

the sound of a baroque orchestra. Your ears are open, so you shape

it starting from what you have and what you hear. That way it doesn’t

become a cheap imitation of something else. It’s music-making in

its own right, and the same as if a pianist were to play Bach or some earlier

music that was written for the harpsichord. You don’t necessarily

want to just imitate a harpsichord sound on the modern piano. You

want to use the capacity of the piano as well because you can’t truly imitate

the harpsichord sound, or it comes out sounding like an imitation.

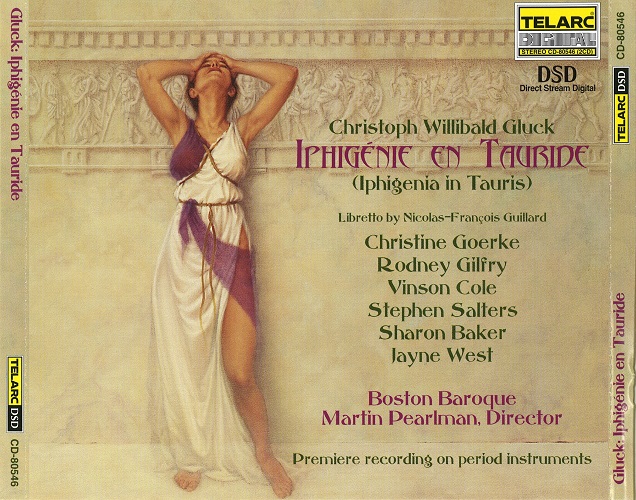

BD: So you’re pleased with it? [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown above, see my interviews with Vinson Cole, and Rodney Gilfrey.]

BD: So you’re pleased with it? [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown above, see my interviews with Vinson Cole, and Rodney Gilfrey.] BD: Would you ever try to write something

in the baroque style because you’re so steeped in it?

BD: Would you ever try to write something

in the baroque style because you’re so steeped in it?

© 2000 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 30, 2000. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.