Pianist Gail Quillman

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

I met Gail Quillman at her studio in downtown Chicago in mid-March of

1989. Her soft-spoken demeaner belied the knowledge and wisdom she

presented in both her music and speaking.

Portions of the conversation were aired on WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago

to promote concerts and celebrations of Leo Sowerby.

Here is the entire interview . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Let’s talk about Leo Sowerby.

How did you get so immensely interested in him?

Gail Quillman: He was one of my teachers.

When I was a freshman at the American Conservatory, I studied theory with

him, starting out in his harmony class. It was love at first sight,

I must say.

BD: Was it love at first sight, or love at first

hear?

Quillman: Sight. The hearing came much

later. He was a wonderful man with a great twinkle in his eye all

the time, even when he was being very strict. At one of our first classes,

as he was grading my homework he told me I had the best stems in the class,

which was very entertaining, and the whole class loved it. That formed

the base of our relationship. It was a very good student-teacher

relationship. He had a wonderful sense of humor, and I just loved

him.

BD: Did this love work both ways?

Quillman: I think so. He liked me, too.

A couple of months later, I was around the corner in an old used-book-and-music

store, and ran into one of my fellow students. He asked me how I

liked the Conservatory, and I said I just loved it. He asked who was

my favorite?” and I said, “Leo Sowerby, of course! He’s a great man.”

That fellow student said he had written a lot of music, and showed me about

five stacks each of which was a foot high. The next time I went into

class, I backed in very modestly and humbly, thinking that I was in the

presence of this great man all this time.

BD: When you came to discover the music that he

had written, was there anything that surprised you?

Quillman: He had great emotional depth, but it

was big and important, which was just the opposite of the personal image

that one got from knowing him. That was a great surprise.

BD: Are you still discovering new things in these

pieces?

Quillman: Oh yes, every time. To me, he’s

the equivalent of Brahms — it’s

endless discovery. Every time you play it, there’s something new.

BD: In all of the music that you’ve played, have

you ever run across anything that you wish you could have changed just

a little bit? Maybe move a note here, or change a dynamic?

Quillman: Oh, no! [Laughs] When one

rehearsed with him, you’d get through a whole work of many pages, and

after you’d finished he’d say, “Now, on page thirty-two, I wrote an F-sharp.”

He knew his music.

BD: When you play these pieces over and over again,

do you change your interpretive style at all over the years? Do you

play them the same way now that you did when you first learning them?

Quillman: I try to be more true to the score each

time. Whatever music I’ve played, I’ve tried to be true to the score.

BD: Is there really only one way to play that

score, or any score?

Quillman: No, I don’t think so. One interprets

when reading the score.

BD: Is there a little bit of you when you play

Mr. Sowerby?

Quillman: I like to think there’s a lot of Mr.

Sowerby in the score, and I hope it comes through that way. I hope

what I’m playing is Sowerby. That’s what I want it to be.

BD: Do you ever run across any pieces that you

just don’t care for, and you leave that work aside?

Quillman: Of Sowerby’s music? No, I haven’t

come across anything I didn’t care for.

BD: He was a superb teacher of theory and composition.

Did you study composition with him, also?

Quillman: Oh yes, composition and music history.

He was also a wonderful music history teacher. He had many out-of-print

books, and he’d quote from the books. It was wonderful.

BD: He lived until 1968. Toward the end

of his life, was he particularly pleased with the then growing avalanche

of recordings of all kinds of music?

Quillman: He didn’t speak of it to me, no.

BD: Was he optimistic about where music was going?

Quillman: I’m sure he was.

BD: Do you do any composing yourself?

Quillman: [Emphatically] No! It’s

a full-time job, and if one performs, one can’t also compose... at least

I have never been able to.

BD: You’re both a performer and a teacher.

How do you balance those two portions of your life?

Quillman: It’s very difficult finding enough time

for myself and my students. But teaching enriches one’s performance.

It emphasizes what you’re trying to do yourself.

BD: So, you really learn at the same time that

you’re teaching?

Quillman: Oh, absolutely. It’s the best teacher

there is. As a matter of fact, when I first began studying theory,

Dr. Sowerby was already living in Washington, and I was very thrilled that

I had been put in the theory department at the Conservatory. I wrote

to him and told him about it, and he wrote back and said, “There’s nothing

like teaching for a good a review.” [Both laugh] So, that’s

what teaching is.

BD: Was he pleased to be here in Chicago?

Did Chicago offer enough outlets for him to perform and to write and to

have his compositions played?

Quillman: If he had been displeased, he wouldn’t

have indicated it to anyone. He was the kind of person who did the

work when it was time to do the work, and he did it as thoroughly as possible.

I don’t think he was negative at all.

BD: Is the sound of his music always positive?

Quillman: I think so. [Photo

at left of Leo Sowerby is from the Library of Congress]

* * *

* *

BD: You’ve been teaching piano since 1960.

Have you also been teaching theory and history?

Quillman: Not history. I’ve taught theory,

composition, counterpoint, harmony, sight-singing, and piano.

BD: How has teaching of music to young students

changed in nearly thirty years?

Quillman: My teaching has changed in as much as

I have changed, because I’ve gotten older. My teaching has gotten

more precise, and more individual.

BD: Are there differences between the students

of 1960 and now?

Quillman: Oh, sure! [Laughs] The students

in 1960 were very determined to express their individuality, and now they’ve

become more serious about the music itself. It’s

not so much about themselves as getting into the music, and communicating

that way. In the 1960s I was teaching at the Conservatory, so I had

a lot of college people, and their comments indicated they couldn’t get

into it, or they couldn’t do this, or they couldn’t do that. There

was a lot of attitude, and now people study because they want to.

They’re much more optimistic, and they don’t have the expectations from

music that they did in the ’60s. Back

then, music was some sort of answer, and now it’s some sort of quest.

It’s an education; it’s a richness; it’s a luxury.

BD: What, for you, is the purpose of music in

society?

Quillman: It keeps the universe going, actually.

[Laughs] It’s the one form of communication that’s the most spiritual

of all of the arts. I believe that. I often say to my students,

“Be careful of what you’re putting out. Don’t put out mistakes. Do

you really want to put that into the air? Let’s be careful about

what we communicate here.”

BD: How is someone who is writing a piece, or playing

a piece, able to tell whether what they’re putting out is right or a mistake?

Quillman: Their teacher tells them.

BD: Yes, but then they’ve got to get away from

the teacher and be on their own. So how can they learn to discern

what’s right?

Quillman: If they discern what’s true to them,

then that’s right.

BD: Will that change over each lifetime?

Quillman: Undoubtedly, many times.

BD: As you teach young pianists, do you find that

the whole shape of society is influencing the way they come to the piano,

as well as the way they come to the classroom?

Quillman: [Ponders a moment]

BD: Let me change it a little bit. Again,

with this avalanche of recordings, do you feel that students are more informed

about all kinds of music today than they were twenty or thirty years ago?

Quillman: I think so, and there’s a hunger for musical

education in parents. They’ve realized that this is an essential

part of their child’s upbringing. One mother told me that music teaches

her child how to study everything else, and how to learn everything else.

When a child studies music, they go to a lesson and there’s

something given to them, or shown to them. Then it’s up to them.

They go home for a week, and what they do with it is up to them.

It’s not like going to school every day, and learning this is right and this

wrong. In music, they have to make that discovery for themselves,

and that’s one of the only areas in their life where that happens. It’s

important.

BD: We’re talking basically about concert music.

Is concert music really for everyone?

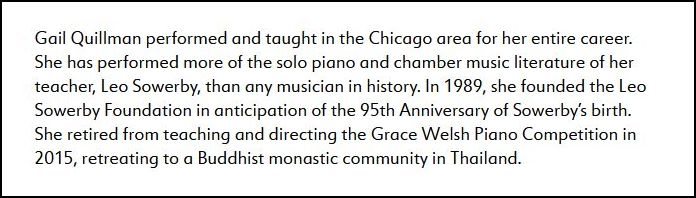

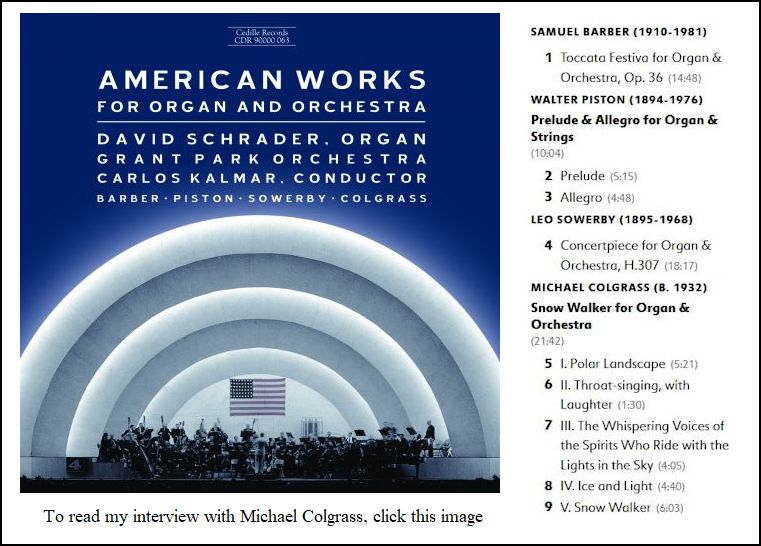

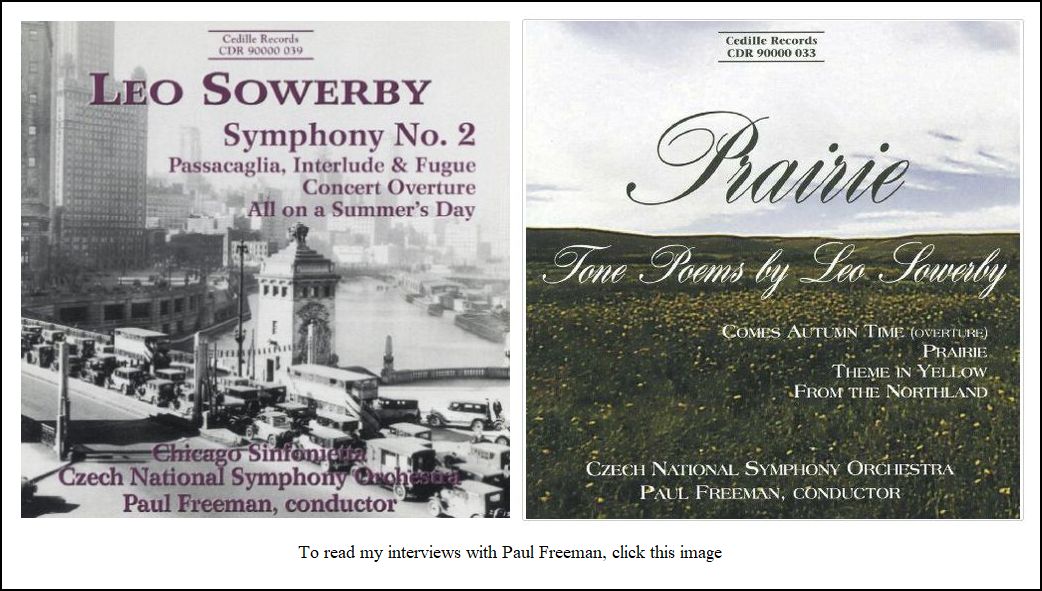

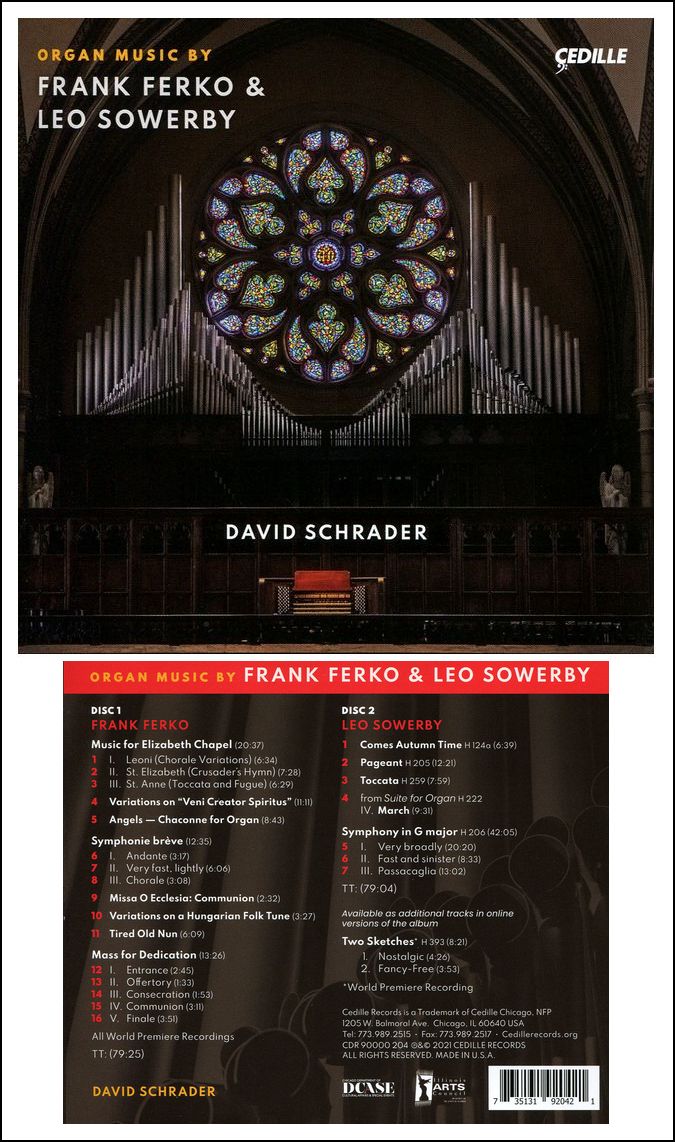

Quillman: No, but it doesn’t have to be. [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Frank Ferko, and David Schrader.]

BD: Should we try to get the kids who go to rock

concerts, into the opera houses and concert halls?

Quillman: They’ll get there sooner or later.

After all, if Mr. Solti’s

planning to play at Madison Square Garden, anything can happen. [Both

laugh] Look at the movie scores — Mozart,

Beethoven, and Rachmaninoff are all getting into it.

BD: Almost unwillingly, or unwittingly.

Quillman: Unwittingly is the better word.

BD: When you play a concert, do you try to include

some new music, or music of Sowerby each time?

Quillman: Oh, absolutely.

BD: What do you expect of the audience that comes

to hear one of your concerts — if

anything at all?

Quillman: I expect them to enjoy the music.

BD: All of it??? Even the unfamiliar?

Quillman: Yes, even the unfamiliar! Music

all comes from the same source, and there’s something in it for everyone.

BD: Do you go to great lengths to express the

Sowerby works in any different way than you do Beethoven, or Haydn, or

Schubert?

Quillman: Only in that I know his personality, and

I knew him personally. I somehow feel that I knew Haydn, too.

I feel quite close to Haydn, and he’s one person that I would really have

liked to have known personally. They all had different personalities,

and it’s important for a performer to know as much as possible about the

personal life of the composer that they’re playing. It’s more important

to me than listening to other performances of the music.

BD: Performers should dig in, and read biographies,

and get into that person’s life?

Quillman: Yes. The spirit of the person

is what should come through the music.

BD: Rather than listening to other performances?

Quillman: Yes.

BD: Do you keep up with other performances yourself

at all, or not really?

Quillman: As a rule, I don’t like to listen to

other performances of the pieces that I’m working on myself. I like

it to come directly through me. If I’m working on a Beethoven piece,

for instance, I enjoy listening to a Beethoven symphony, or a quartet to

get to know Beethoven the person, rather than another pianist’s interpretation

of Beethoven.

BD: Besides solo piano pieces, do you also include

some chamber works?

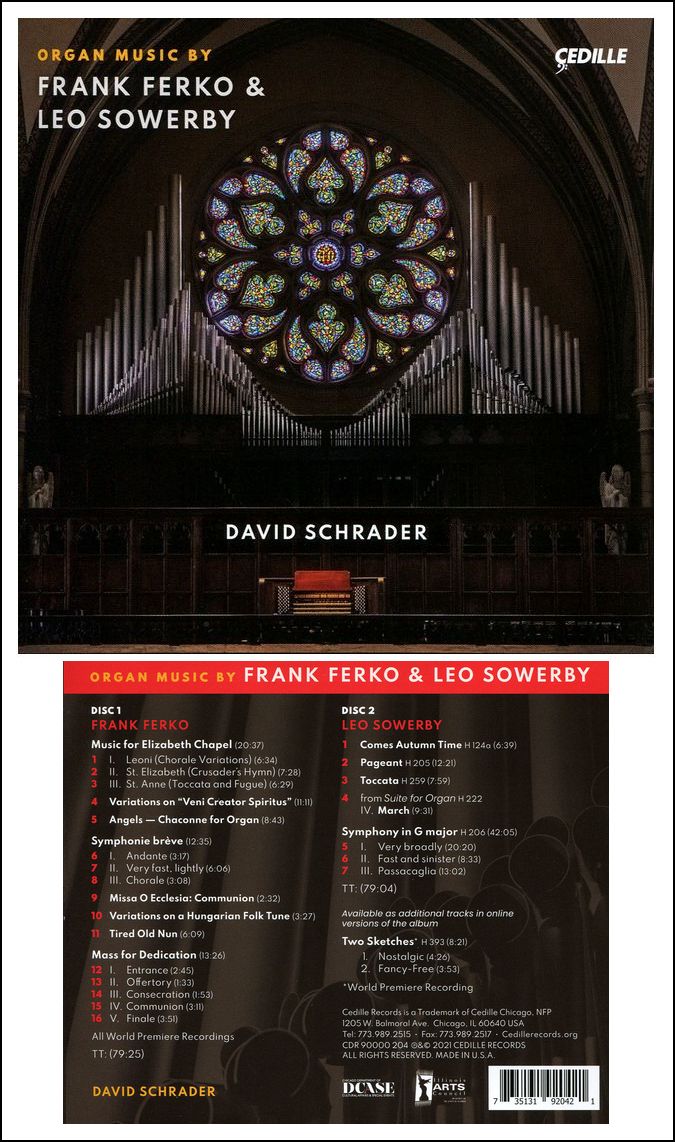

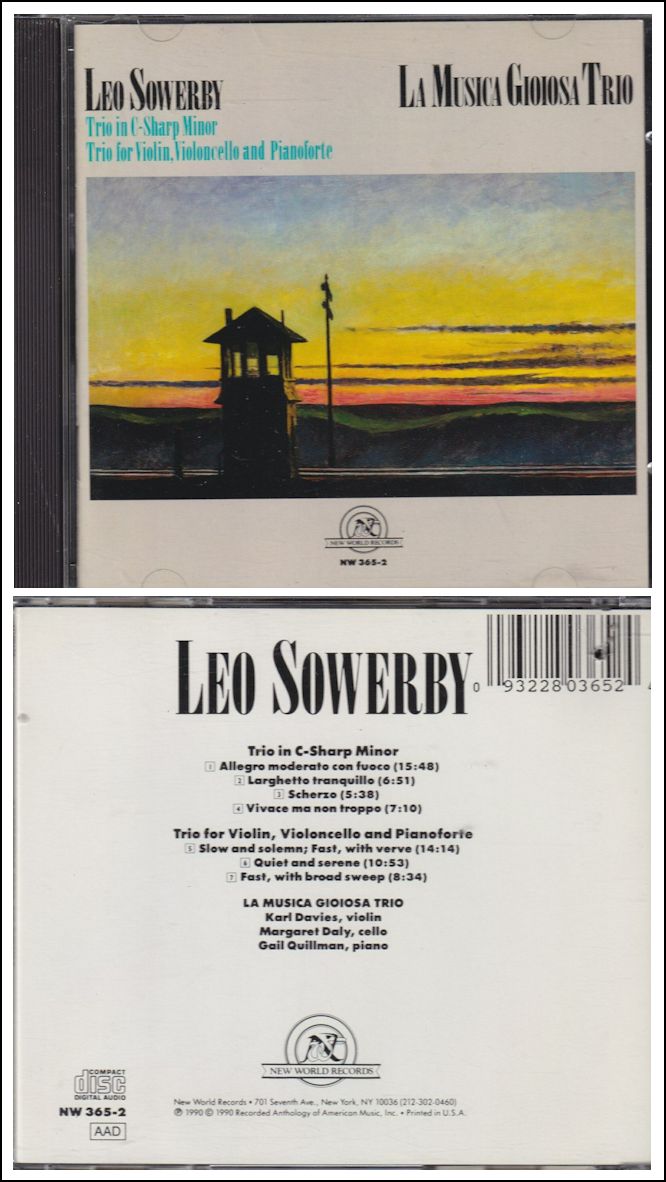

Quillman: Yes, we have a trio, La Musica Gioiosa.

BD: Joyful Music!

Quillman: Right, that’s it!

* * *

* *

BD: From the vast repertoire of solo and chamber

music, how do you decide which pieces you will spend some time on, and

which you’ll have to let go?

Quillman: Right now, my main interest is Leo Sowerby’s

music, and getting it published. The way I’m going to get it published,

I hope, is to play it enough so other people will want to play it, and

then the publishers will realize that there’s a demand for it. As

to the trio, there are three of us, so we suggest different things, and put

our programs together that way.

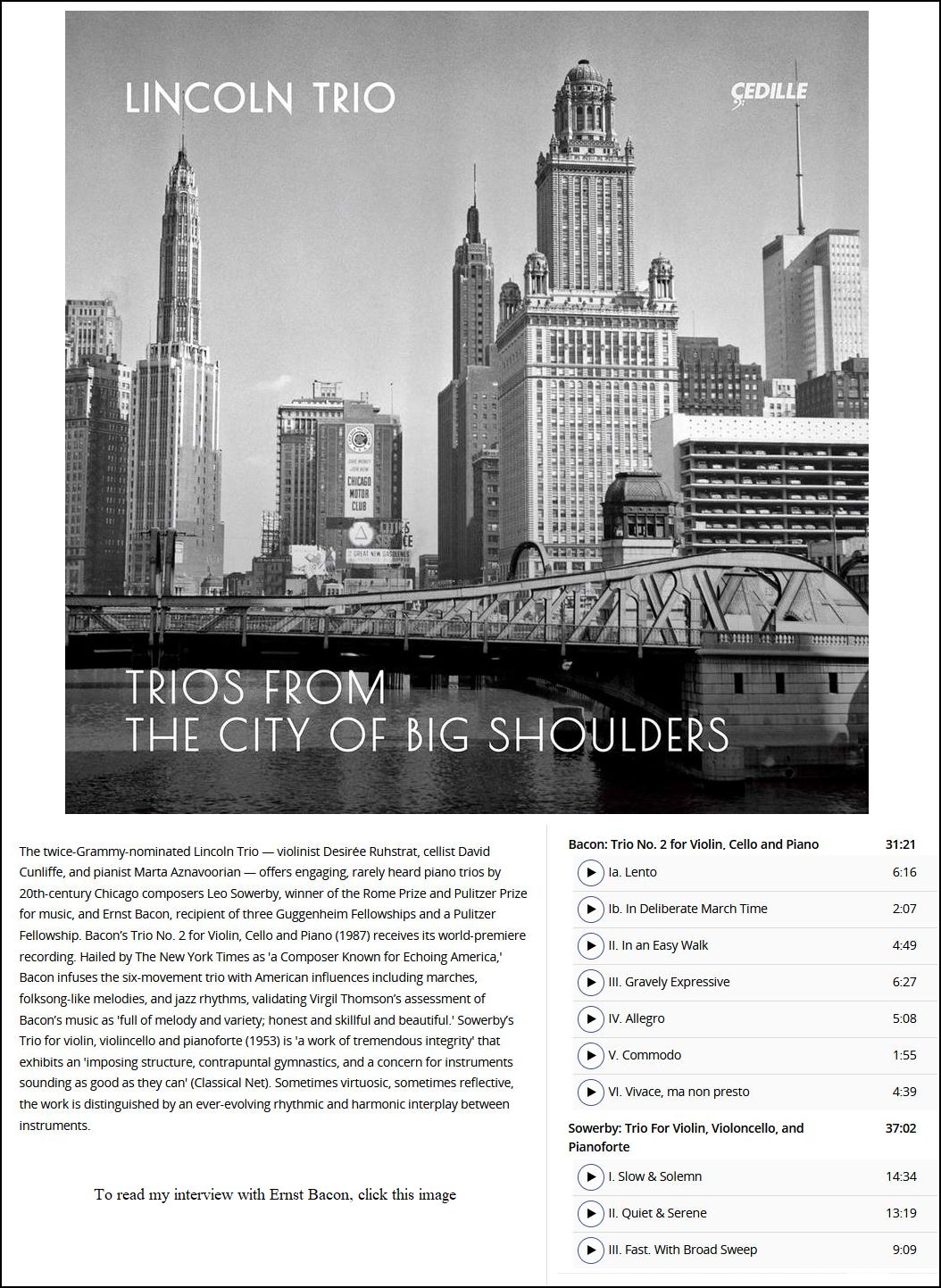

BD: Did Sowerby write a lot of chamber music?

Quillman: We have found three trios, and I have

access to two of them. So we’ll be performing those.

BD: Where’s the third? Is it locked up in

a vault some place?

Quillman: I don’t know. It’s a very young

work, and it’s undated, so it may be lost.

BD: You’ve never ever seen it?

Quillman: No, I haven’t seen it.

BD: Do you know anything about it other than it’s

just an entry in the catalogue?

Quillman: It’s catalogued, yes.

BD: Now you’ve got this one recording out. Are

you going to be putting out more recordings yourself?

Quillman: Hopefully, yes, I plan to.

BD: Are they solo, or chamber works?

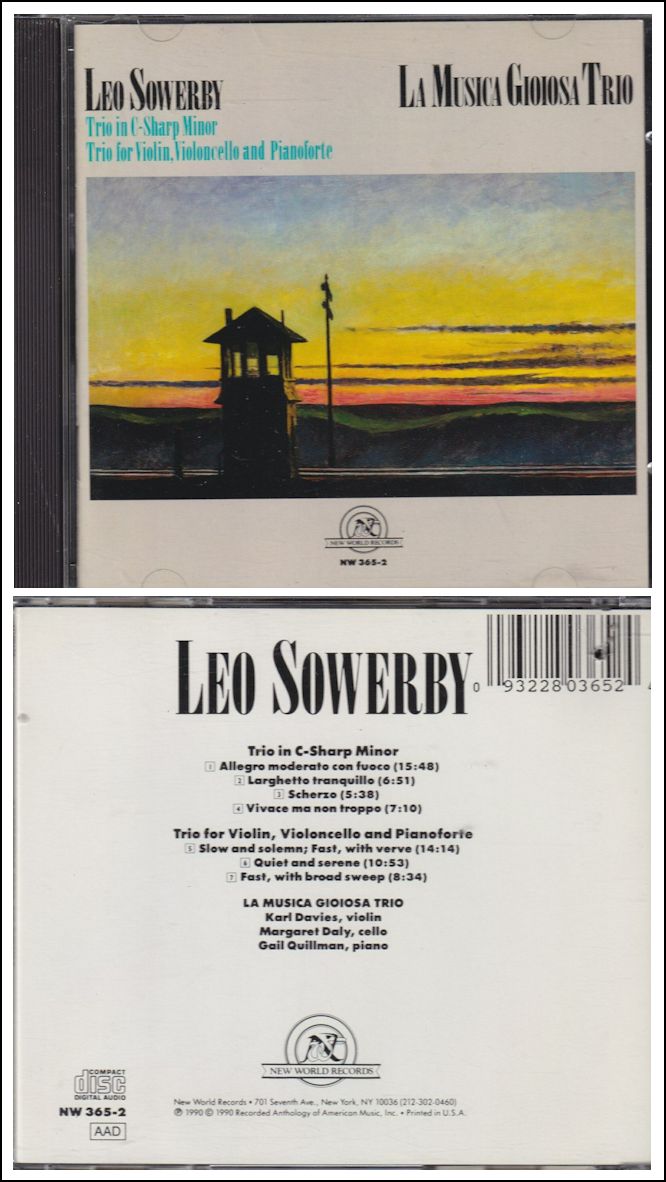

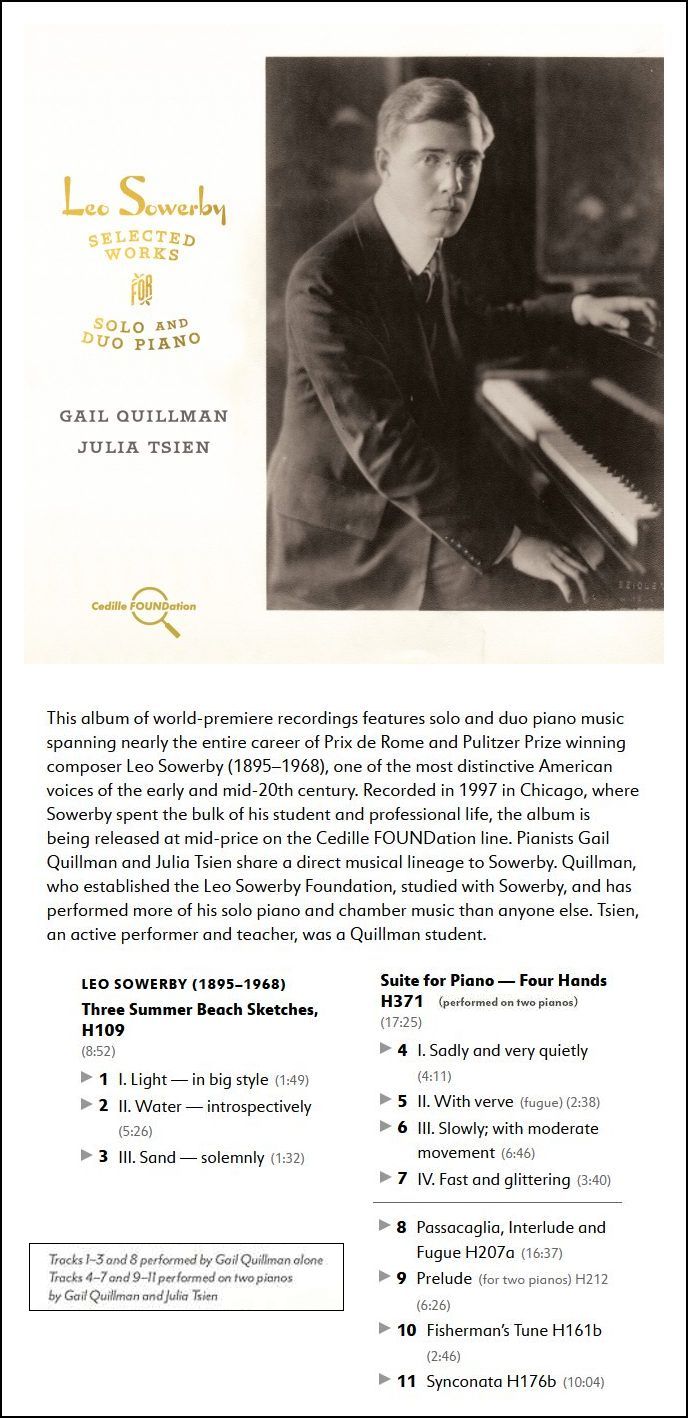

Quillman: Both. I’m working on a Passacaglia,

Interlude, and Fugue at the present time, which is a solo work, and

then we hope to record the two trios of 1911 and 1953.

BD: Are the three pieces that are on your solo CD

very different from one another, or are they similar in structure and style?

Quillman: They’re all different. The Sonata

is a big work, probably the most important piano work that is overlooked.

The Suite is a shorter work, and a more recent work, and

the Passacaglia is, as the name implies, after an organ sostenuto

bass work. It’s very different.

BD: Sowerby was an organist as well as a composer.

Are his piano works pianistic, or are they organistic, but written for

the piano?

Quillman: They are pianistic because, although it’s

not well known, Sowerby was a masterful pianist. When he was younger,

he was quite a brilliant pianist. He had one of his concerts in Chicago.

He played the piano part for the Concerto [March 5, 1920], and

it was later that he got into playing the organ.

BD: Did you hear him play the piano, and play

his own works?

Quillman: No. I heard him play the piano when

he corrected our studies and compositions, but I didn’t hear him play his

own works.

BD: Are there any recordings of him playing?

Quillman: I don’t know. I doubt it.

He was a very modest man.

BD: That seems like a contradiction, to be a

composer and yet be a modest man. How can you reconcile those two?

Quillman: He may have been one of the chosen ones.

BD: He was a great composer in your eyes?

Quillman: Oh, yes.

BD: What is it about his music, or any music,

that makes it stand above the crowd and become great music?

Quillman: Number one, the spirituality of the

music. Number two, the fact that the music survives. No matter

who plays it, it’s worth a great, great deal.

BD: No one can kill it?

Quillman: Nobody can kill it! It comes through,

it really does.

* * *

* *

BD: You’re a performing pianist, and you go and

play on different instruments. How long does it take you to adjust

to each new instrument that you play?

Quillman: Sometimes never! [Laughs]

BD: Keyboardists are a victim of whatever instrument

is put in front of them. They can’t carry it around with them.

Quillman: Well, luckily, I was taught in the tradition

to play with a light arm, and be quite relaxed. I have found that

rather than trying to play the piano, if I just play the music, then the

piano is going to sound its ultimate best. So I’ve

ceased fighting pianos.

BD: You just bring out as much as you can?

Quillman: I just play the way I play, and it may

be a subconscious adaptation on my part. My hands may just adapt

subconsciously.

BD: Is the music really flowing through your

hands, or are you becoming part of that music, and becoming the sound that

comes out of the piano?

Quillman: One hopes to be becoming the music

— mind, heart and hands. I think

of that when I play.

BD: When you’re recommending that young students

start studying a piece, or a series of pieces, do you have favorites that

you pick on all the time, or do you tailor each lesson plan to the individual

student?

Quillman: Each individual. I’m always looking

for new things. I very seldom repeat myself.

BD: So, once you get beyond the basic technique...

Quillman: ...yes, then it’s very individual.

BD: How did you wind up in Uruguay?

Quillman: There was a competition there. When

I would compete, I’d see the same people in Spain and Italy, and you talk

about where the next contest was going to be, and try to make it. I

suppose I found out about it that way, and went to it.

BD: Did you win that competition?

Quillman: No, I didn’t win that one. I can’t

remember what I did, but I won a prize.

BD: Is that the best way to go for young pianists

— to do whole bunches of competitions?

Quillman: I found it was invaluable. When one

is from Chicago, and you spend maybe fifteen years competing, and playing

at the music clubs, and using up what Chicago has to offer. You

get very localized, and the competitions are really eye-opening. It

was wonderful. The first time I went to compete I didn’t do very well,

but it gave me a real sense of where I stood internationally. In Chicago

you get involved with all the local things, and all of a sudden you say,

“Here I am! I’m an American!” and you find this whole bigger scope

opens up. It’s valuable just for that.

BD: Is there any chance that all the studios and

all of the schools in America, and the world, are turning out too many

young concert pianists?

Quillman: Oh, I don’t think so. I think

there’s room. There aren’t enough halls. That’s what there’s

not enough of. People would love to play, but there aren’t enough

facilities, and there’s not enough support. That’s what we need.

We need small halls. There is wonderful talent, especially here in

Chicago.

BD: You have a son. Have you

encouraged him to go into music, or have you urged him to stay out of

that life?

Quillman: He went into music, and then he went

into business. [Laughs] His heart is with music, but he found

it wouldn’t support him.

* * * *

*

BD: You and the Trio play in a music shop?

Quillman: At the Steinway dealer, yes. It’s

a beautiful sound.

BD: Is that nice to play in that kind of environment?

Quillman: People have loved the series.

They think it’s wonderful to be so close to the musicians. It’s

informal, and very friendly. They love it. We’ll also be playing

at the Newberry Library, and while that will be a more formalized setting,

it will be the same kind of thing. We will be on a level with the

audience, so it’s going to be nice.

BD: Do you talk to the audience, and explain the

music a little bit, or just come out and play?

Quillman: We come out and play, but there is coffee

and sherry afterwards. That’s when we talk.

BD: Do you like the response that you get from

the crowd?

Quillman: We’ve gotten wonderful response.

I never dreamt that we would get such a lovely response. People love

it.

BD: What advice do you have for audiences who come

to hear piano recitals, chamber music, even orchestra concerts?

Quillman: To enjoy it. Let the music come

to them.

BD: They shouldn’t be asked to do any work, or

be involved in the performance?

Quillman: No, no. If they became involved,

they’d get in the way. The less selfless that they are, the more

they’ll enjoy the music, and the more they’d listen. The less they

think the better. The music will speak to them.

BD: You view music as an emotion, rather than

a cerebral activity on the part of the listener?

Quillman: One could react to it emotionally,

but one doesn’t necessarily have to. A better term would be ‘spiritual’

rather than ‘emotional’.

BD: You seem to have the spirit of the music inside

you, and it comes out.

Quillman: I’d love it if that were true.

BD: What is next on the calendar for you?

Quillman: One of my goals is to perform Sowerby’s

Concerto. I’m going to be working on that as soon as I get

the score.

BD: You’ll learn it, and then induce someone to

conduct it?

Quillman: Absolutely, yes.

BD: What kinds of pianos do you have in your studio?

Quillman: I now have a Stein and a Knabe.

The Stein was one of 2000 made by a man who worked for Story & Clark,

and decided to go off on his own. It’s a very good piano, but he

couldn’t sustain his business, so he only made a few thousand.

BD: It’s got a good action, and a good feel?

Quillman: Yes, it’s a good piano.

Charles Frederick Stein established his firm in Chicago in 1924 after

many years of working with Mr. Hampton L. Story (of Story & Clark).

The factory was located at 3047 West Carroll St., Chicago. Mr.

Stein’s personal vision was to build the world’s finest pianos, and his

instruments were known to be of superior quality and craftsmanship.

At first the firm built only grand pianos and grand player pianos,

but later introduced upright and studio pianos to their line in 1931. One

of Charles Frederick Stein’s more memorable inventions was a “tone chamber”

located between the strings and soundboard, patented in 1934.

Charles Frederick Stein went out of business in 1942 with the

onset of World War II. The firm only built pianos for 18 years, and

instruments by Charles Frederick Stein are quite rare today. |

BD: Do you like the response of the Knabe?

Quillman: Yes, it’s also a good piano.

BD: Do you always teach on one and let the student

play on the other, or do you go back and forth?

Quillman: Usually I teach on one, and have the

student on the other.

BD: I like being in this studio.

Quillman: It’s very Gothic. [After looking

around the room a bit, we came back to Sowerby] It was in 1962

that he sent me the manuscript of the Sonata.

BD: Then he was in Washington, DC?

Quillman: Yes. He sent it with the instructions

that I was just to copy the fugue, which is the third movement, because

he was still revising the first two movements. I had written to

him, asking him for a contest piece. I was in a scholarship competition,

and so he sent that to me to copy. In a letter he said, “It’s a pretty

good fugue, but it really tears the place apart!” He later sent

me two other copies, one that was complete and revised. Then in 1968

he sent me another copy, which I thought was strange. It just came

out of the blue, and he had a letter with it in which he told me that he

felt I deserved it. I wrote a thank you note, but didn’t have a stamp.

When I got the newspaper the next day, I read of his death, and I thought

that it was his way of communicating to me.

BD: You have been championing his music ever since?

Quillman: Ever since. I felt that it was

meant for me to do.

BD: Should every major composer have a champion,

either a conductor or a performer that will just simply focus in on that

one composer, and present the music?

Quillman: That happens, ultimately there seems

to be a person who sees something in the music that other people haven’t

seen. There is no other Sowerby! Sowerby is an outstanding

American composer, and people are just now beginning to realize the intrinsic

worth of the music. It’s unique. The Fugue

was the jolliest thing that he had ever written, and that’s when I decided

it was time to record it.

BD: I’m glad you’ve been able to interest the record

company in doing it.

Quillman: I am too, and it wasn’t hard going.

I had written to Angel Records and sent them a tape, and they recommended

me to New World. They were doing American twentieth-century music,

and in a few days they just accepted it, and agreed to do it. So,

it was very lucky.

BD: I’m glad he has such an able spokeswoman as you!

Quillman: Oh, thank you.

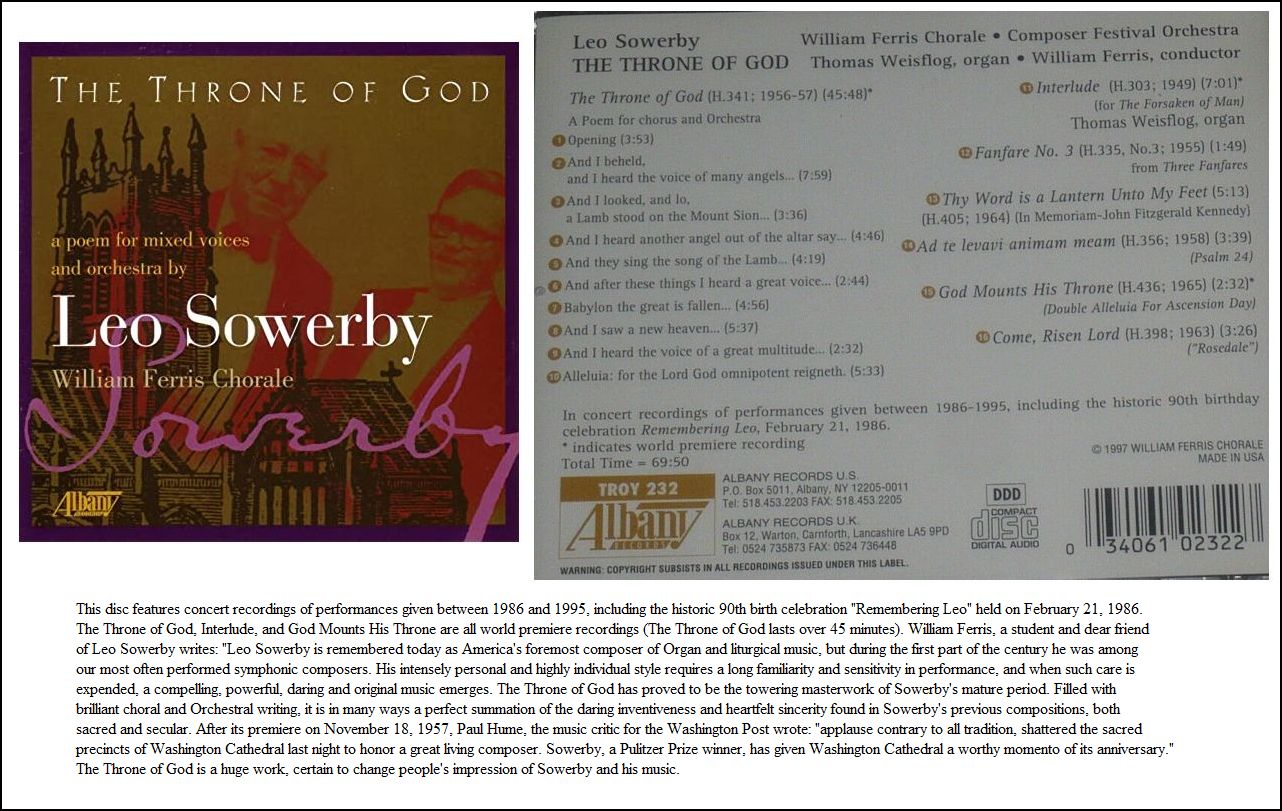

BD: Tell me about how you met William Ferris.

Quillman: We were both students of Sowerby. We

passed each other in the hall, and became quite friendly. There are

offices next to my studio here, and I was playing through the Sonata

a couple of years ago when John Vorrasi came to my

door and said, “That’s Sowerby! I know that’s Sowerby!” I said

it was. They were doing a ‘Remembering Leo concert’, and in conjunction

with that, they were having a program at the Newberry Library. So,

they asked me to play the Sonata there. That’s the night I

felt Sowerby was really with us. The Ferris Chorale was also going

to perform The Throne of God, and record it.

BD: Thank you so much for all of your work, and for speaking

with me today.

Quillman: It was my pleasure. Thank you.

© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Quillman’s

studio in Chicago on March 16, 1989. Portions were broadcast on WNIB

the following year, and again

in 1995 and 2000. This transcription

was made in 2022, and posted on this website

at that time. My thanks to

British soprano Una Barry for her

help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this

website, click here.

To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as

well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster

Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975 until

its final moment as a classical station in

February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared

in various magazines and journals since 1980, and

he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to

visit his website for

more information about his work, including

selected transcripts of other interviews, plus

a full list

of his guests. He would also like to call your attention

to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.