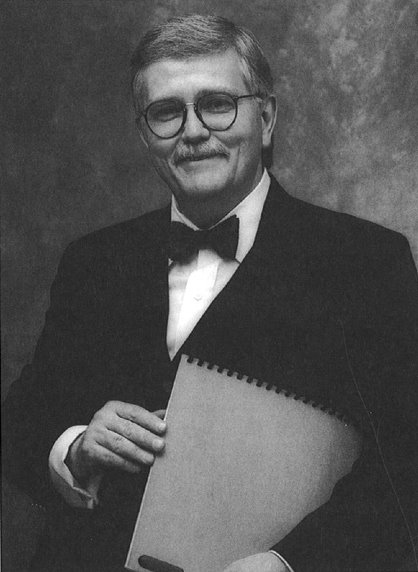

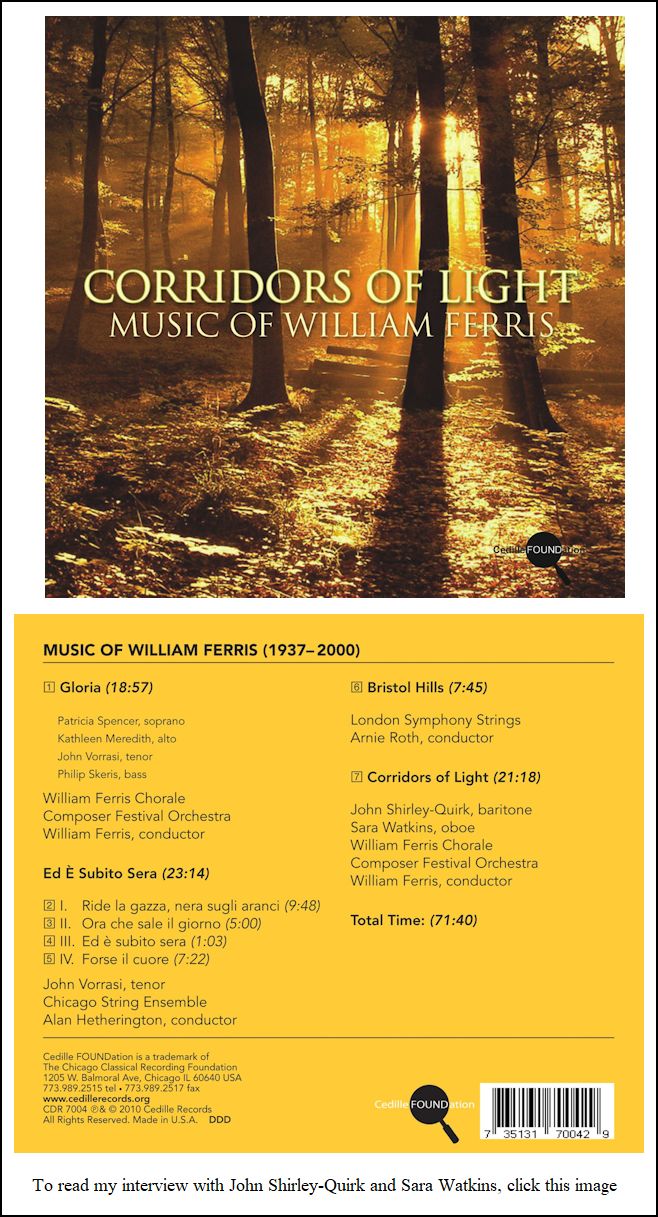

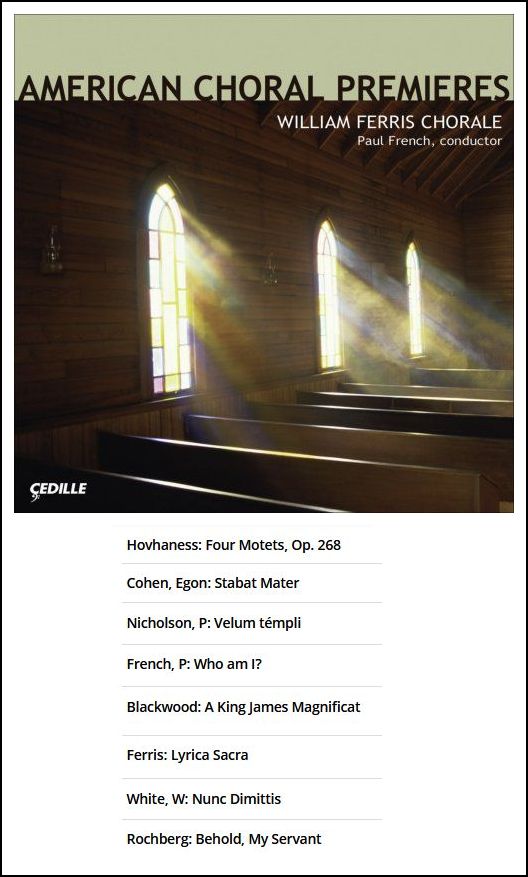

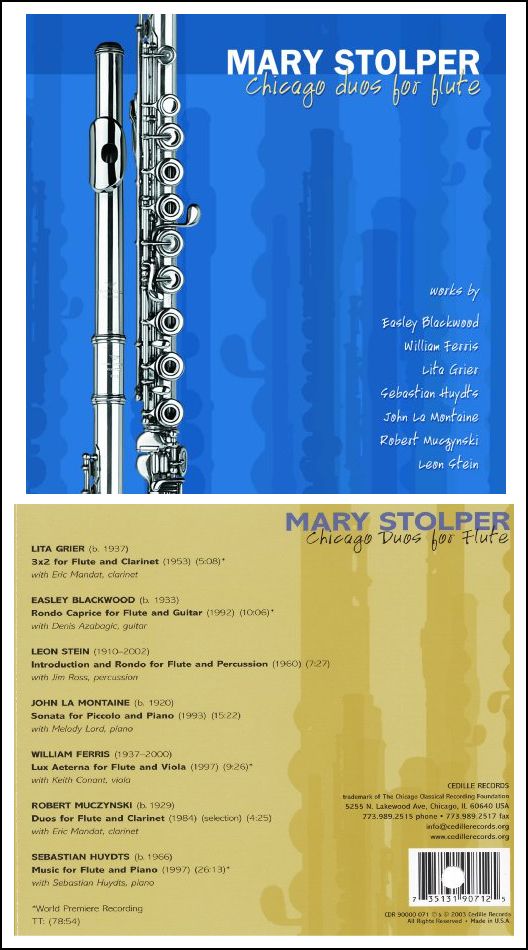

WILLIAM FERRISWilliam Ferris (1937–2000) was a lifelong champion of contemporary composers. He and the William Ferris Chorale, which he founded with tenor John Vorrasi, have been acclaimed for their concerts of music by Dominick Argento, Samuel Barber, John Corigliano, David Diamond, Lee Hoiby, William Mathias, John McCabe, Edward McKenna, Gian Carlo Menotti, Steven Paulus, Vincent Persichetti, Ned Rorem, William Schuman, Leo Sowerby, William Walton, and many others, often with the composers as honored guests. Under his direction, the Chorale performed at the Aldeburgh Festival and the Spoleto Festival: USA and has given more than 160 world, American, and Chicago premieres of important new literature. A renowned composer in his own right, Mr. Ferris’s music was commissioned and premiered by the Chicago and the Boston Symphony Orchestras. Among his compositions are two operas, numerous concerti, symphonic and chamber works, hundreds of choral works, and dozens of songs. Northwestern University houses his complete musical archive. A man of devout faith, Mr. Ferris worked for the Church from his early youth, holding positions as organist/music director and composer-in-residence at Sacred Heart Cathedral in Rochester, New York, and, most notably, at Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church in Chicago. It was his profound belief that music for the liturgy should be of the highest quality, and his work is a shining example of that principle. Mr. Ferris’s sudden death, while conducting a rehearsal of the Verdi Requiem, shocked the music community. His was a unique and distinctive voice on the American music scene. ==

From the William Ferris Chorale website (with additions)

|

BD: How many people are in

the Chorale?

BD: How many people are in

the Chorale? BD: Do you feel that because

you’ve built up a solid reputation that you can take a few more

risks?

BD: Do you feel that because

you’ve built up a solid reputation that you can take a few more

risks?

BD: Let’s talk about some of your compositions.

Earlier we were talking balancing a one-composer program.

When you’re writing a piece, do you look for balance within your

own output?

BD: Let’s talk about some of your compositions.

Earlier we were talking balancing a one-composer program.

When you’re writing a piece, do you look for balance within your

own output?|

Published 4/05/2016

An awards panel of judges drawn from the Illinois Council of Orchestras Board of Directors and independent professional musicians from throughout Illinois reviewed the nominees. The RSO is also pleased to announce that Larsen has also renewed his contract to serve as RSO Music Director through the 2019/20 season. In his 25th season as Music Director of the Rockford Symphony Orchestra, Larsen has also been a recipient of the ICO Conductor of Year Award in 1999 and 2006. His tenure has brought both local and national recognition to the orchestra. Larsen has worked with dozens of orchestras in the United States and Europe, including the Opera Theater of San Antonio, the Chicago Opera Theater, Lyric Opera Cleveland, the Minnesota Opera, Michigan Opera Theater, Light Opera of Chicago and the Netherlands Radio Chamber Orchestra. “The RSO is fortunate to have a conductor of Steve Larsen’s caliber leading the orchestra”, Executive Director Julie Thomas said after the announcement. “We look forward to continued excellence in programming and performance quality.” |

BD: I don’t mean just in this instance...

BD: I don’t mean just in this instance... Ferris: On the whole, yes I am, and I’m also enlightened

because it makes me realize that there isn’t just your own singular

approach to the work. That’s very, very rewarding for the

very simple reason that it means your notation works. What you’ve

put down, your directions, somehow or other really committed to paper

a nice road map for a performance.

Ferris: On the whole, yes I am, and I’m also enlightened

because it makes me realize that there isn’t just your own singular

approach to the work. That’s very, very rewarding for the

very simple reason that it means your notation works. What you’ve

put down, your directions, somehow or other really committed to paper

a nice road map for a performance.At this point, we stopped for a few moments to take care of some technical details, and then continued . . .

John S. Edwards (July, 1912 - August, 1984),

the executive vice president and general manager of the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra from 1967-1984, and was regarded as the 'dean of

American symphony orchestra managers,'

John S. Edwards (July, 1912 - August, 1984),

the executive vice president and general manager of the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra from 1967-1984, and was regarded as the 'dean of

American symphony orchestra managers,'Sir Georg Solti, CSO music director, praised Edwards as 'a person with infinite wisdom to whom I often turned. And his advice, not always what I wanted to hear, was in the long term always right.' Edwards was born in St. Louis. He studied English at the universities of North Carolina and Harvard, and worked for a brief time as a reporter and music critic for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. He left the paper to join the publicity department of the St. Louis Symphony and in 1936 became assistant manager of the National Symphony. Edwards returned to St. Louis three years later as manager of the

Orchestra, and held similar posts in Los Angeles, Baltimore, Pittsburgh

and Washington. He was the first recipient of the Louis Sudler Award "for distinguiched

service to the profession of symphony orchestra management" and also

received honorary doctoral degrees from DePaul University and the

Cleveland Institute of Music. For many years Edwards was an

influential leader in the affairs of the American Symphony Orchestra

League, serving as their fifth president and later as Chairman of the

Board for 15 consecutive seasons. In 1975, he was recipient of

the League's Gold Baton award, the highest national award for distinguished

service to music and the arts. [The photo is from a commercial website, hence

their ‘watermark’] |

BD: A bad performance of contemporary

music will really kill it.

BD: A bad performance of contemporary

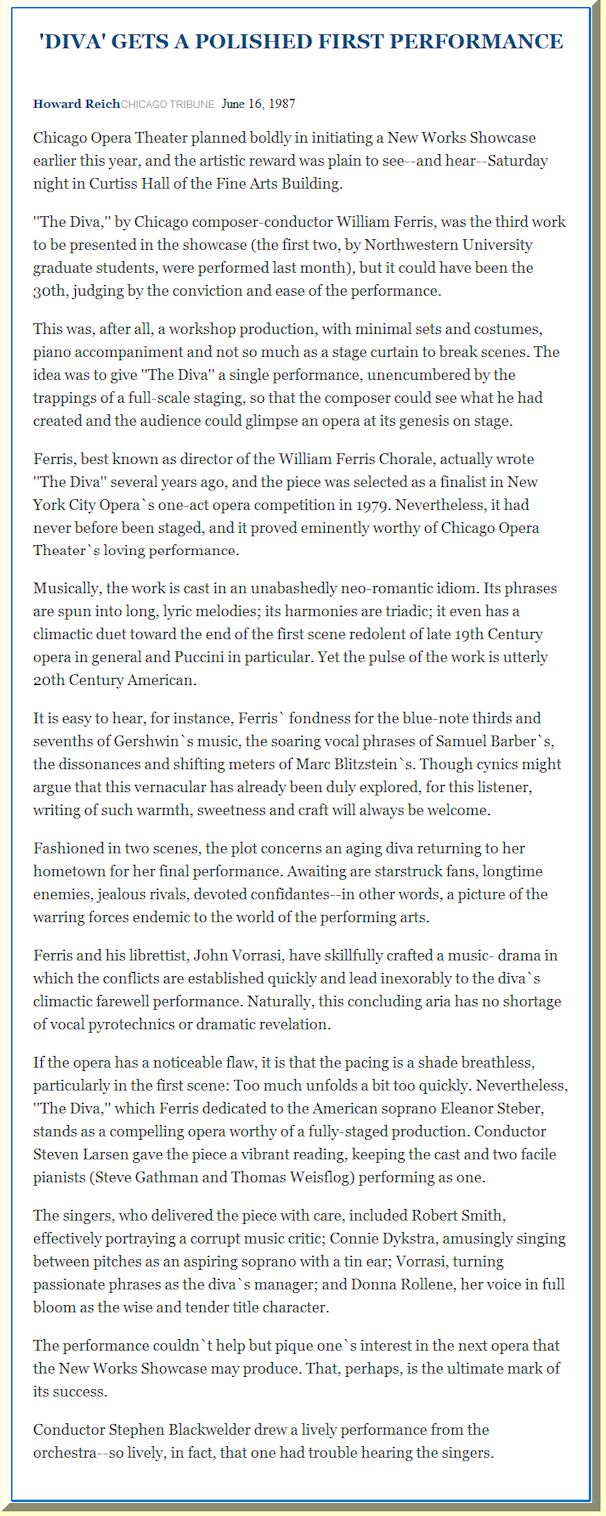

music will really kill it.Ten and a half years later, in May of 1997, we met again, ostensibly to promote upcoming performances of his opera The Diva at Northwestern University. We did, indeed chat about that, and while there is a bit of duplication of ideas from the previous conversation, there is much new material, as well as his thoughts on other subjects. Rather than edit out the repetitions, here is that second interview . . . . . . .

BD: We know you from conducting

your Chorale, and from your compositions for the Chorale, and your

instrumental compositions. Now we’re going to learn a little

bit about you as an opera composer. Tell me a bit about The

Diva. When was it written, and how did it come about?

BD: We know you from conducting

your Chorale, and from your compositions for the Chorale, and your

instrumental compositions. Now we’re going to learn a little

bit about you as an opera composer. Tell me a bit about The

Diva. When was it written, and how did it come about? Ferris: Oh, yes, I do. I respect and love

the voice, and I try, even in my instrumental writing, to make things

sing in the most general sense, because the voice is so absolutely

elemental, and yet so toweringly expressive. When you add to

it a wonderful text, where you’re communicating on that level, too,

there’s not anything quite like it. Working all these years with

singers — both alone in unaccompanied

music, and then doing so many Twentieth-century things with different

instrumental ensembles — I always

believed the voice is the sovereign ingredient of all these things, and

probably always will be.

Ferris: Oh, yes, I do. I respect and love

the voice, and I try, even in my instrumental writing, to make things

sing in the most general sense, because the voice is so absolutely

elemental, and yet so toweringly expressive. When you add to

it a wonderful text, where you’re communicating on that level, too,

there’s not anything quite like it. Working all these years with

singers — both alone in unaccompanied

music, and then doing so many Twentieth-century things with different

instrumental ensembles — I always

believed the voice is the sovereign ingredient of all these things, and

probably always will be. BD: You work with texts so much. Is it

more difficult, or is it perhaps a nice break, to have no text?

BD: You work with texts so much. Is it

more difficult, or is it perhaps a nice break, to have no text? Ferris: There’s never enough

time, because I am the Music Director of a large church music program

at Mount Carmel Church, and there’s the Chorale. But I do reserve

days where I’m just a composer and nothing else. Once I have

my ideas, I work very quickly. I’m pretty disciplined. I

know how to get the stuff on paper.

Ferris: There’s never enough

time, because I am the Music Director of a large church music program

at Mount Carmel Church, and there’s the Chorale. But I do reserve

days where I’m just a composer and nothing else. Once I have

my ideas, I work very quickly. I’m pretty disciplined. I

know how to get the stuff on paper.These conversations were recorded in Chicago on September 11, 1986, and May 24, 1997. Portions were broadcast on WNIB later in 1986, and again the following year, and in 1997 and 2000. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.