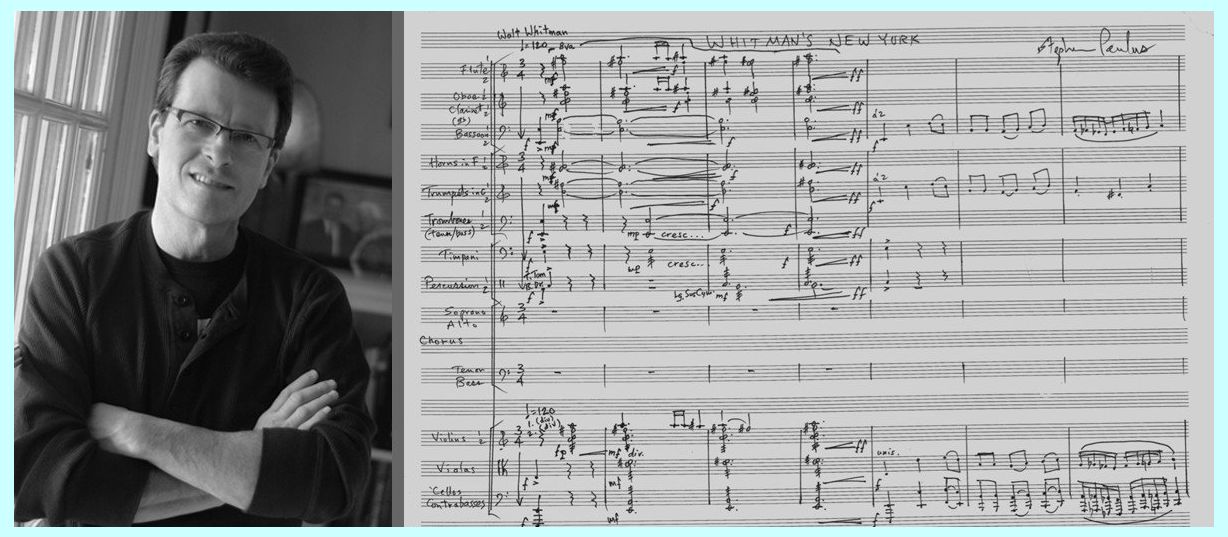

Stephen Paulus (August 24, 1949 – October 19, 2014) was a Grammy

winning American composer, best known for his operas and choral music.

His 1982 opera, The Postman Always Rings Twice, one of several

operas he composed for the Opera Theatre of St. Louis, prompted

The New York Times to call him "a young man on the road to

big things". His style is essentially tonal, and melodic and romantic by

nature.

Stephen Paulus (August 24, 1949 – October 19, 2014) was a Grammy

winning American composer, best known for his operas and choral music.

His 1982 opera, The Postman Always Rings Twice, one of several

operas he composed for the Opera Theatre of St. Louis, prompted

The New York Times to call him "a young man on the road to

big things". His style is essentially tonal, and melodic and romantic by

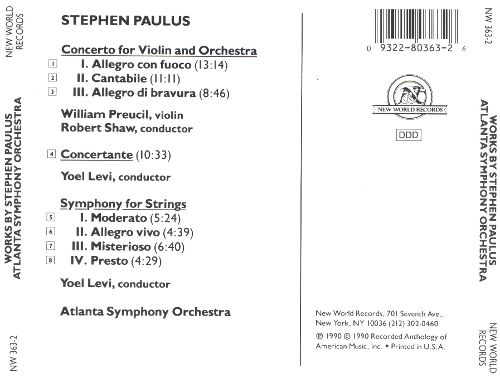

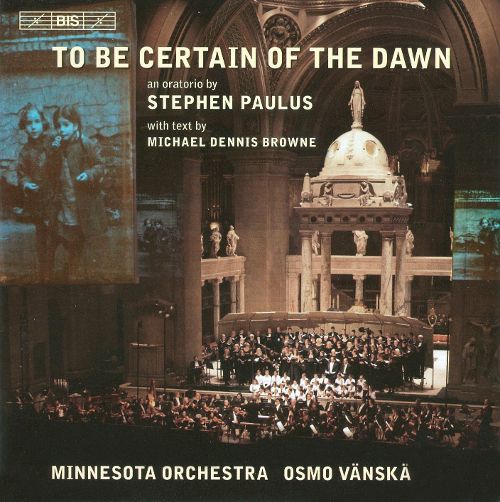

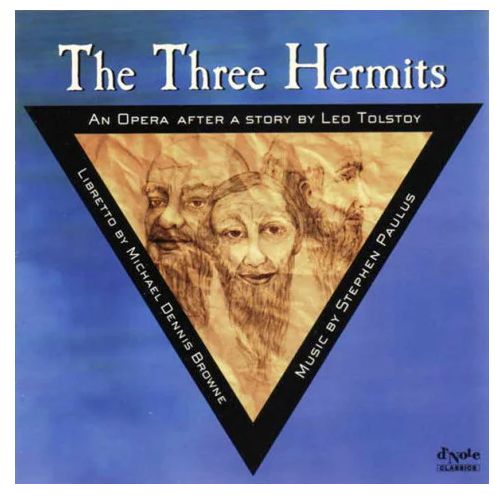

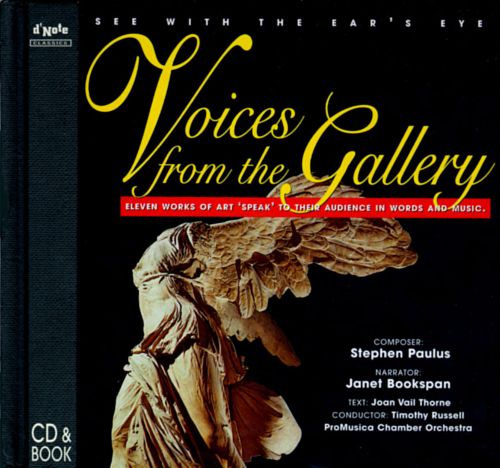

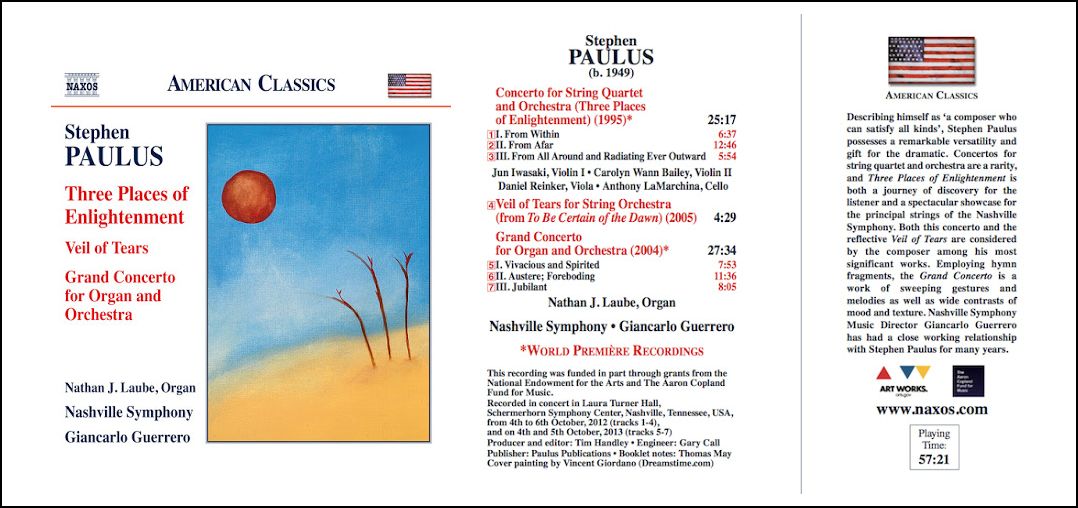

nature.He received grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and Guggenheim FoundationKennedy Center Friedheim Prize. He was commissioned by such notable organizations as the Minnesota Opera, the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, the Saint Louis Chamber Chorus, the American Composers Orchestra, the Dale Warland Singers, the Harvard Glee Club and the New York Choral Society. Paulus was a passionate advocate for the works and careers of his colleagues. He co-founded the American Composers Forum in 1973, the largest composer service organization in the U.S., and served as the Symphony and Concert Representative on the ASCAP Board of Directors from 1990 until his death (from complications following a stroke in July 2013) in 2014. Paulus was born in Summit, New Jersey, but his family moved to Minnesota when he was two. After graduating from Alexander Ramsey High School in Roseville, MN, he attended the University of Minnesota, where he studied with Paul Fetler and eventually earned the Ph.D. in composition in 1978. By 1983, he was named the Composer-in-Residence at the Minnesota Orchestra, and in 1988 he was also named to the same post at the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, whose then-conductor Robert Shaw commissioned numerous choral works from Paulus for Shaw's eponymous vocal ensemble. After the premiere of his second opera, The Postman Always Rings Twice, he began a fruitful collaboration with the Opera Theatre of St. Louis that would result in four more operas. In 1997, he was awarded the Brock Commission from the American Choral Directors Association. In a career which encompassed more than forty years of composition his output came to include over 450 works for chorus, orchestra, chamber ensemble, opera, solo voice, piano, guitar, organ, and band. Paulus lived in the Twin Cities area. -- Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

Bruce Duffie: First of

all, tell me about the joys and sorrows of being a rather tonal

composer as we head towards the end of the twentieth century.

Bruce Duffie: First of

all, tell me about the joys and sorrows of being a rather tonal

composer as we head towards the end of the twentieth century. BD: Do you consider composing a job?

BD: Do you consider composing a job? BD: Have you basically been pleased

with the performances you’ve heard of your music over the years?

BD: Have you basically been pleased

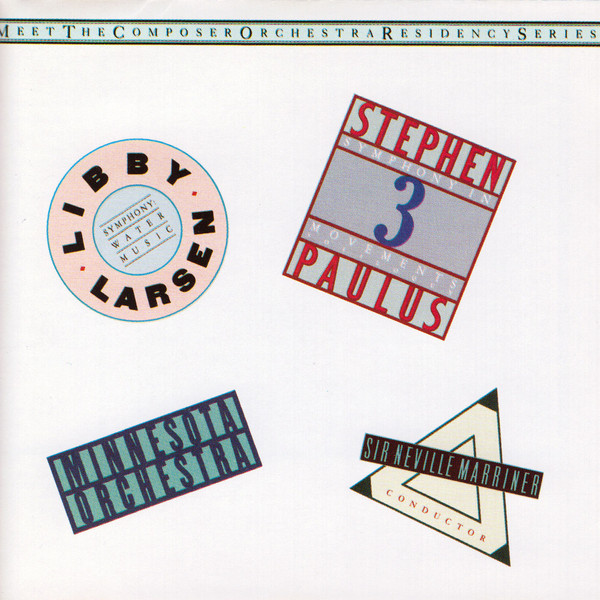

with the performances you’ve heard of your music over the years? BD: Is this something special, because

it is a great orchestra and a great conductor doing your work, and

not just an ordinary orchestra on an unknown label?

BD: Is this something special, because

it is a great orchestra and a great conductor doing your work, and

not just an ordinary orchestra on an unknown label? BD: If someone comes to you and says

“I want to commission you to write a happy

piece,” would you accept it?

BD: If someone comes to you and says

“I want to commission you to write a happy

piece,” would you accept it? SP: I don’t know if there’s so much

of an expectancy, as hope. I would just hope that they are

open-minded enough so that they give it a chance, to listen and form

an opinion based on that. I don’t expect them to like something

or to particularly dislike it, but to be silent and listen

— which is asking a lot these days. Very few

audiences, at least in this country, are truly quiet. There are all

kinds of extraneous noises, ranging from candy wrappers and purses that

sound like the vault at Fort Knox being shut, to vigorous coughing, sneezing,

talking. There are all kinds of interferences which, for a long tim

SP: I don’t know if there’s so much

of an expectancy, as hope. I would just hope that they are

open-minded enough so that they give it a chance, to listen and form

an opinion based on that. I don’t expect them to like something

or to particularly dislike it, but to be silent and listen

— which is asking a lot these days. Very few

audiences, at least in this country, are truly quiet. There are all

kinds of extraneous noises, ranging from candy wrappers and purses that

sound like the vault at Fort Knox being shut, to vigorous coughing, sneezing,

talking. There are all kinds of interferences which, for a long tim

[At this point I needed to make a technical adjustment, and while we were stopped we mentioned several composers, including Hugo Weisgall, Dominic Argento, and Paul Fetler, who were associated with either Minnesota, or the Lyric Opera of Chicago Young Composers Program.]

|

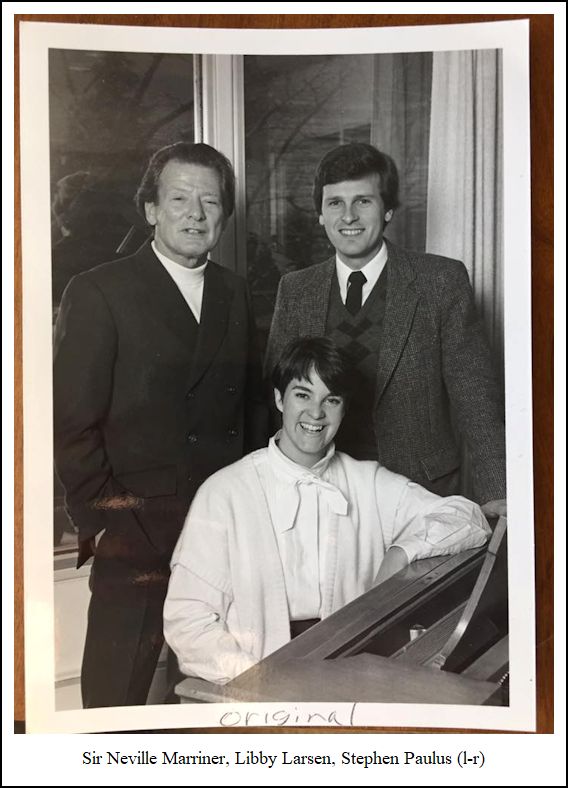

In 1996 the Board of Directors adopted the current name of American Composers Forum (ACF) in recognition of its growing national reach. Eight chapters were established in major urban centers, and the 50-state commissioning program Continental Harmony was launched in 1998 as a millennium celebration in partnership with the National Endowment for the Arts. Among its more singular historical programming was the First Nations Composer Initiative from 2004-2010 to support the unique needs of Native American composers and performers. ACF has a successful history of national education programming. BandQuest®, a series of music for middle school bands composed by prominent American composers, has reached an estimated 625,000 students since its inception in 1997. There are now twenty-two published works in the series ranging from Michael Colgrass, Libby Larsen, Michael Daugherty and klezmer revivalist, Hankus Netsky, to name a few. ChoralQuest® is the newest education program for middle school, with commissions from Stephen Paulus, Alice Parker, Jerod Tate, Jennifer Higdon, and Chen Yi among others. NextNotes®, the newest program, awards promising high school students with meaningful performance and mentorship opportunities. Over the course of four decades, ACF has nurtured the work of thousands of composers. The innova recording label has released over 600 titles, and our BandQuest® and ChoralQuest® series for middle level students has reached over half million students. New programs like ACF CONNECT offer direct connections and commissions with leading national ensembles. The organization has a rich history of granting programs, readings, salons, conferences, and residencies that support the creation of new work and connect composers to communities. Today, ACF has over 1,000 members in all 50 states, including composers, performers, colleges, and universities. Members come from both urban and rural areas; they work in virtually every musical genre, including orchestral and chamber music, world music, opera and music theater, jazz and improvisational music, electronic and electro-acoustic music, and sound art. In addition to the tangible benefits of membership (a profile page in our composer member directory, detailed opportunities listings, legal and professional development advice, professional development workshops, seminars, and networking events), members are part of a national community of artists who share common concerns, aspirations, and goals. -- From the ACF website

|

BD: Because you were tired?

BD: Because you were tired? BD: Let’s talk a little bit about

operas. You’re here in Chicago as adviser to the composer-in-residence

program for Lyric Opera. What are some of the real differences

between writing a symphony and getting it performed, and writing an

opera and getting it mounted?

BD: Let’s talk a little bit about

operas. You’re here in Chicago as adviser to the composer-in-residence

program for Lyric Opera. What are some of the real differences

between writing a symphony and getting it performed, and writing an

opera and getting it mounted?

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on June 10, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1994, 1998, and 1999. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.