|

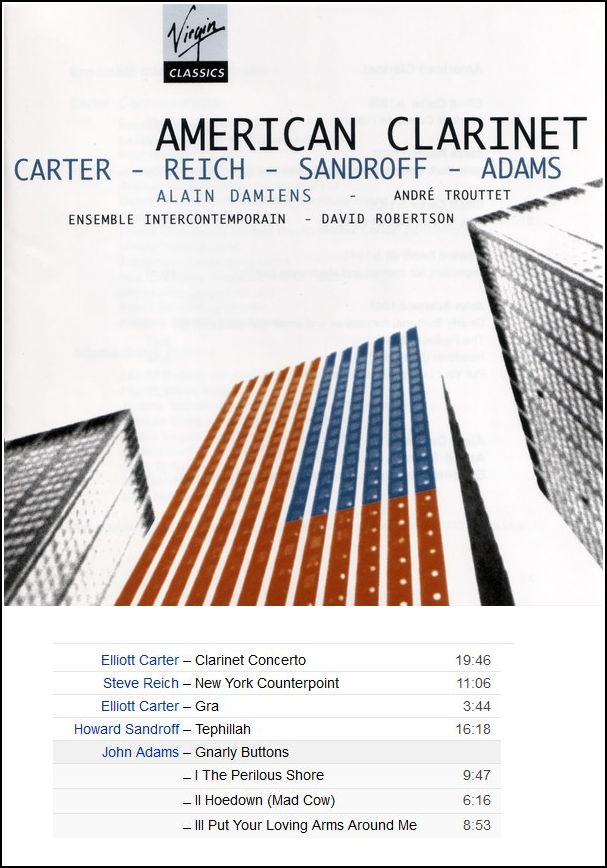

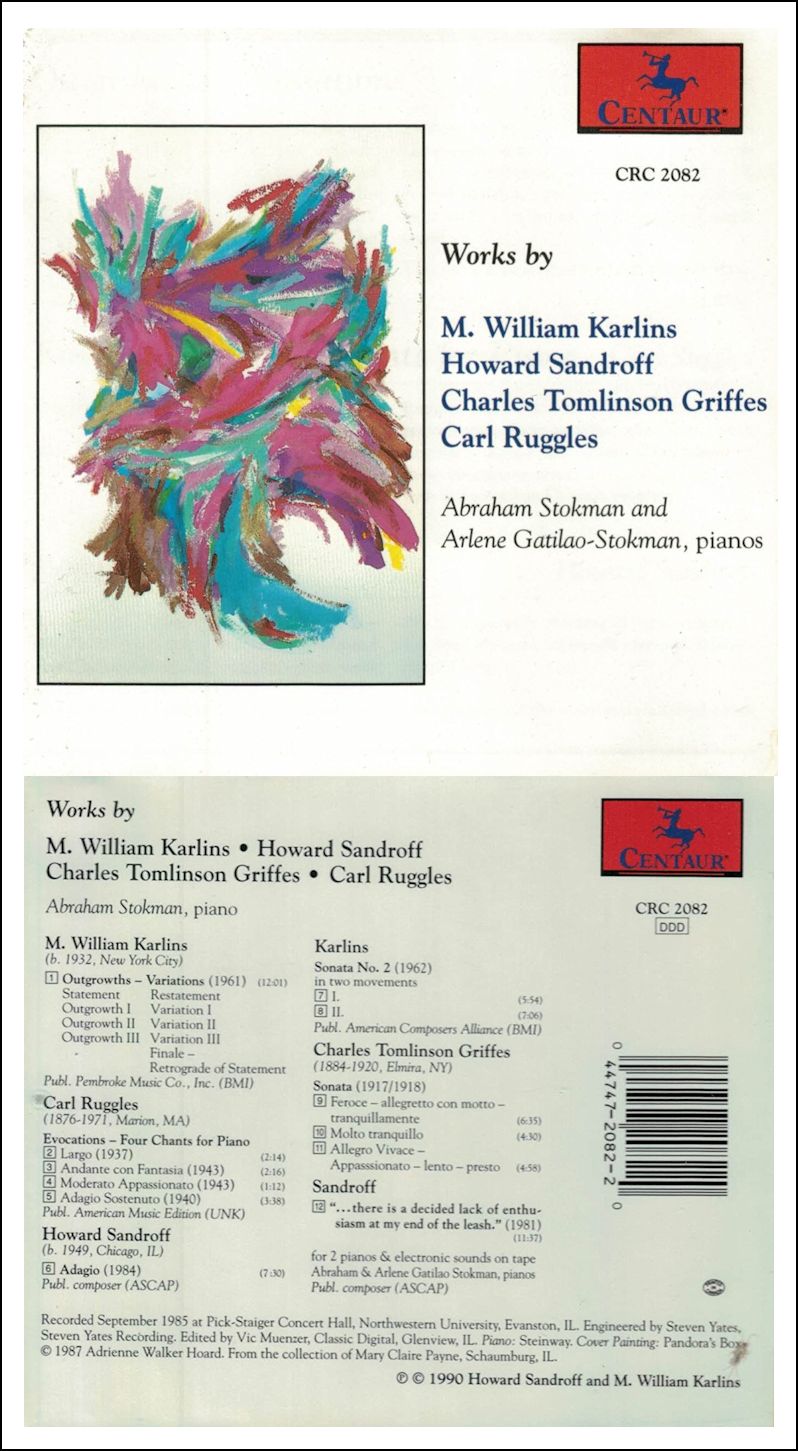

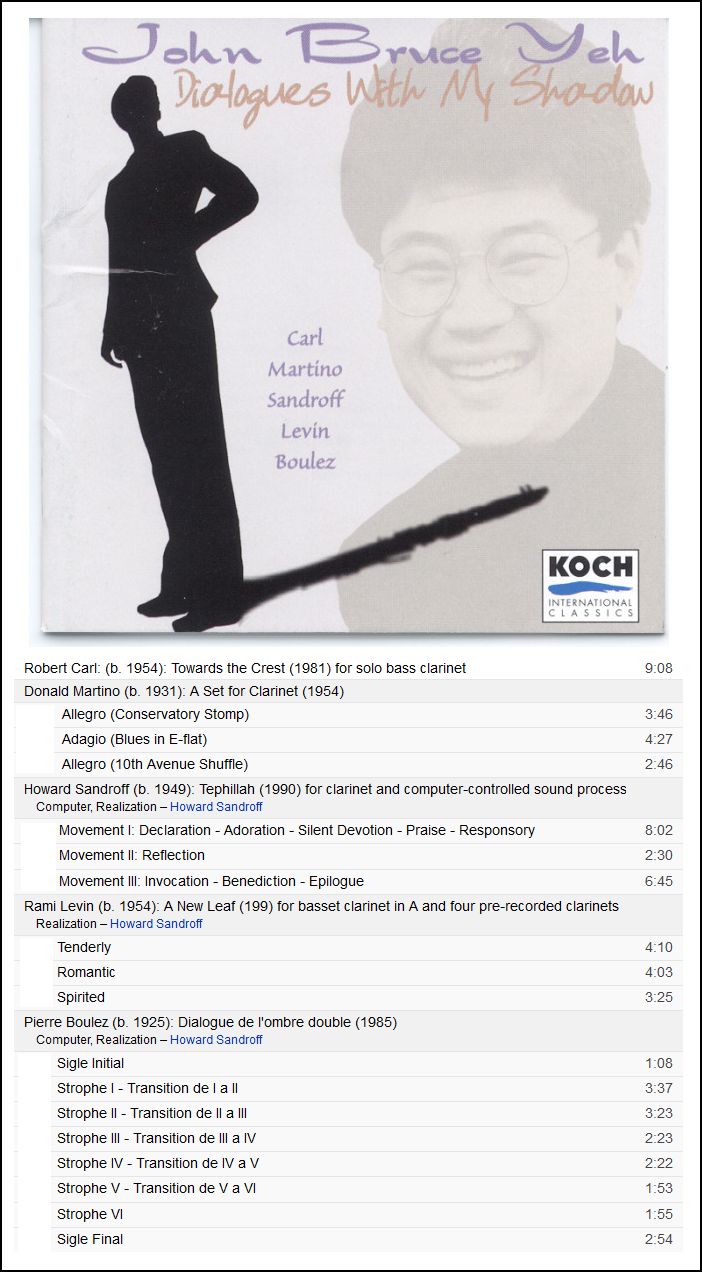

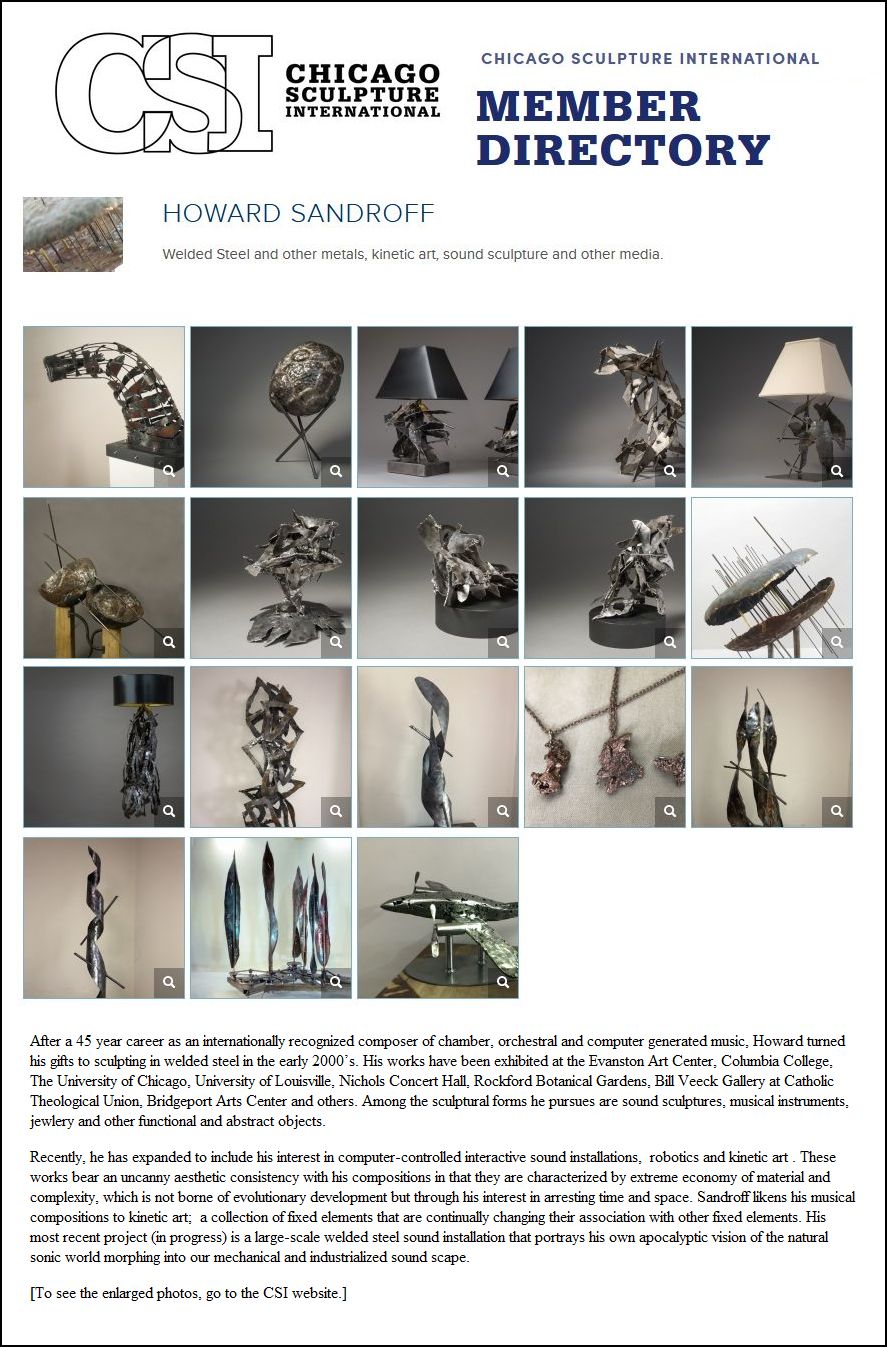

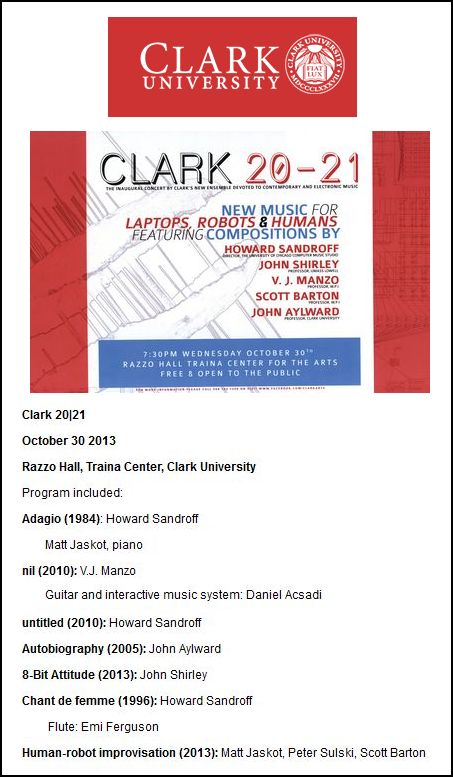

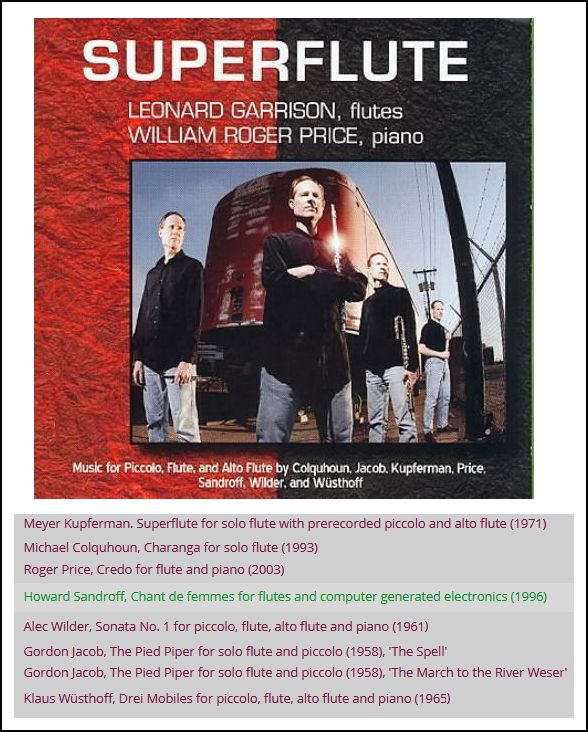

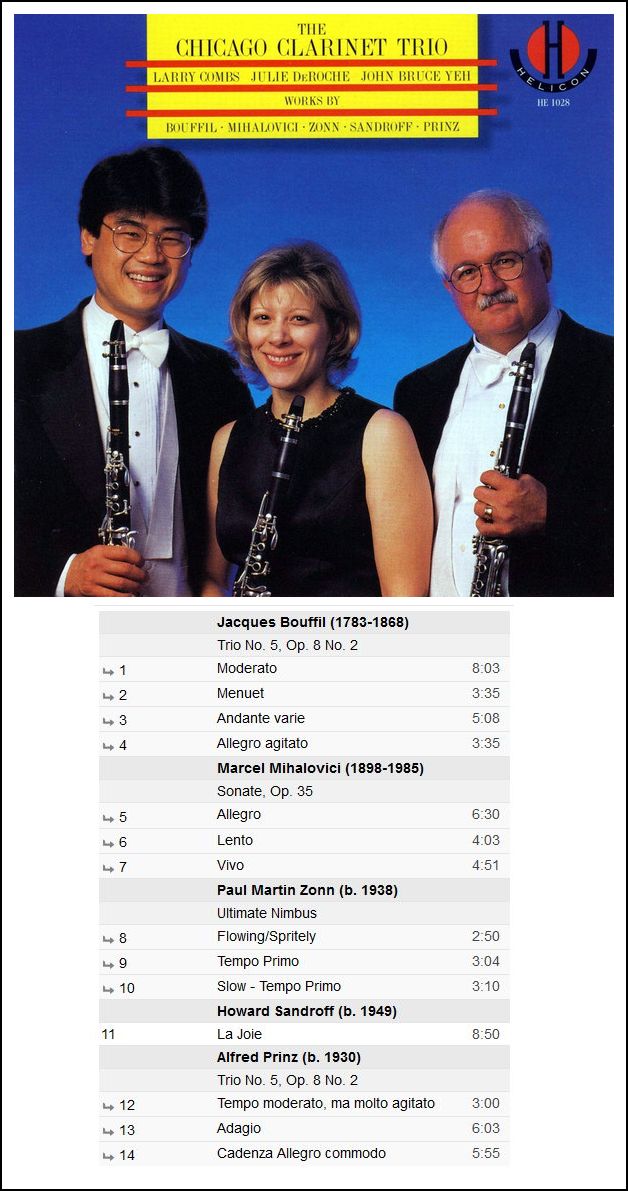

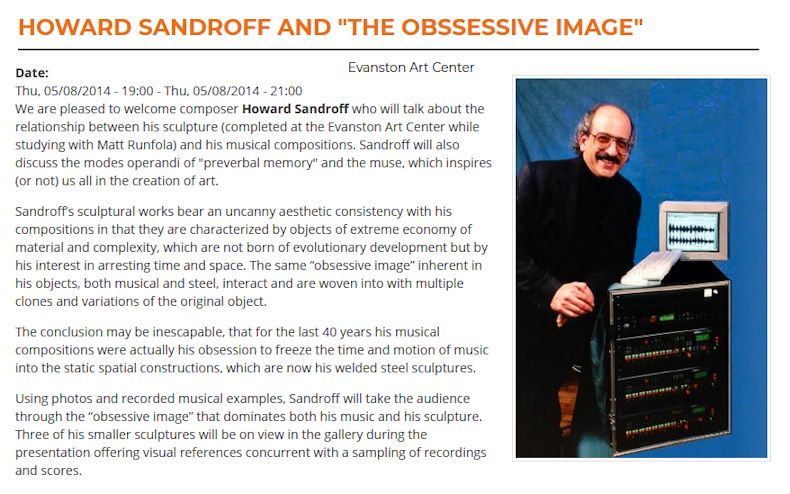

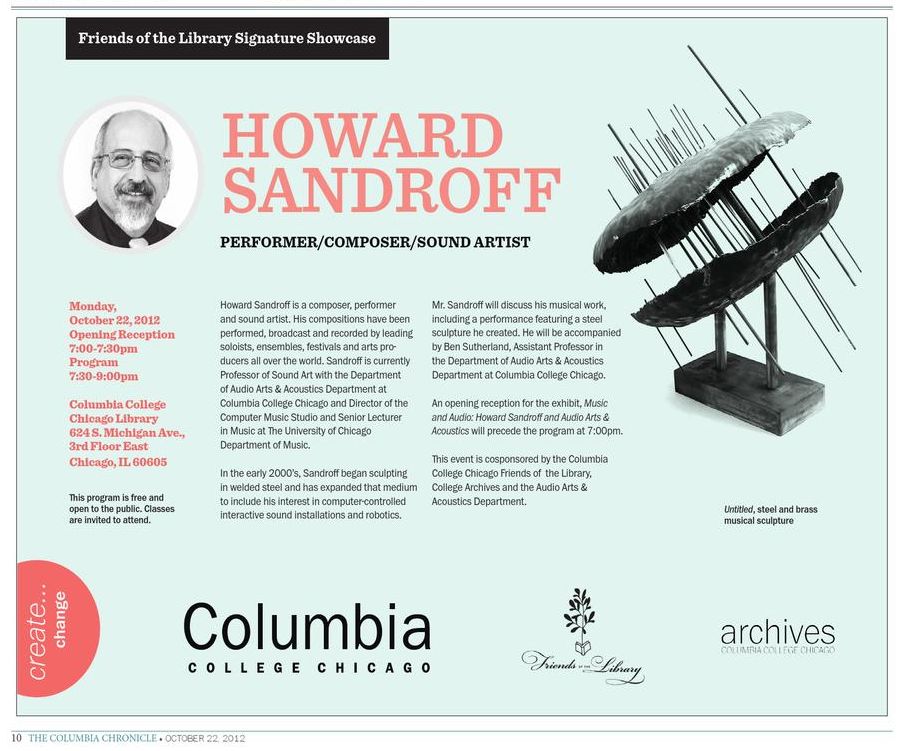

Howard Sandroff (born October 28, 1949 in Chicago, Illinois) is an American composer and music educator. Sandroff studied at the Chicago Musical College of Roosevelt University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His composition instructors included Robert Lombardo and Ben Johnston. He has received composition and research fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the University of Chicago and the Yamaha Music Foundation. He worked as a conductor and director of Chicago's New Art Ensemble, and is a lecturer in music at the University of Chicago, and directs the university's Computer Music Studio. He is also a professor of Audio Arts & Acoustics at Columbia College Chicago. In 2009, Pierre Boulez invited Sandroff to attend the dedication of the new IRCAM facility at the Centre Georges Pompidou. His composition Tephillah, for clarinet and computer, was performed at the dedication by Alain Damiens, clarinetist with the Ensemble Intercontemporain. Sandroff has collaborated with clarinetist John Bruce Yeh, performing Boulez's 1985 work for clarinet and electronics, Dialogue de l'ombre double. Among Sandroff's compositions are works for solo instruments, chamber

music ensembles, and orchestra, often incorporating live or recorded electronic

music. His works have been performed throughout the world in concerts

and festivals such as New Music America, Aspen Music Festival, New Music

Chicago, the International Computer Music Conference, the Smithsonian

Institution, and the World Saxophone Congress. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

Bruce Duffie: [With a wink] Are you a lunatic?

Bruce Duffie: [With a wink] Are you a lunatic? BD: Not even to get another perfect

piece?

BD: Not even to get another perfect

piece? BD: Do you work with it on the page, or are you simply

trying to transcribe what is in your brain onto the page and into

the electronics?

BD: Do you work with it on the page, or are you simply

trying to transcribe what is in your brain onto the page and into

the electronics? BD: So a computer is really not much

different than our old hammer?

BD: So a computer is really not much

different than our old hammer? BD: There may be many threads, but this

is our thread, and we’re stuck with this thread because it’s our thread.

BD: There may be many threads, but this

is our thread, and we’re stuck with this thread because it’s our thread. BD: ...they decided to re-package the

existing material.

BD: ...they decided to re-package the

existing material. BD: I trust you’re not teaching anarchy.

BD: I trust you’re not teaching anarchy. BD: You’re glad to listen to a program

about somebody else?

BD: You’re glad to listen to a program

about somebody else? BD: Shouldn’t the tape be kept in the Sandroff Archive

for future generations to hear how somebody performed the work without

any input from the composer?

BD: Shouldn’t the tape be kept in the Sandroff Archive

for future generations to hear how somebody performed the work without

any input from the composer? BD: I’m glad to know that the rewards

do counter-balance the agonies.

BD: I’m glad to know that the rewards

do counter-balance the agonies.

========

========

========

---- ---- ----

======== ========

========

© 1993 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 5, 1993. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1999. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.