|

José Serebrier (born 3 December 1938) is a Uruguayan conductor

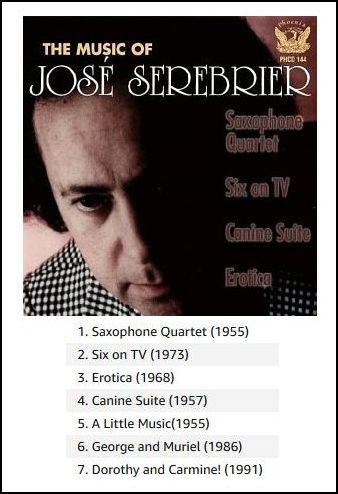

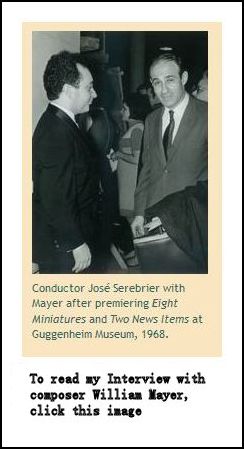

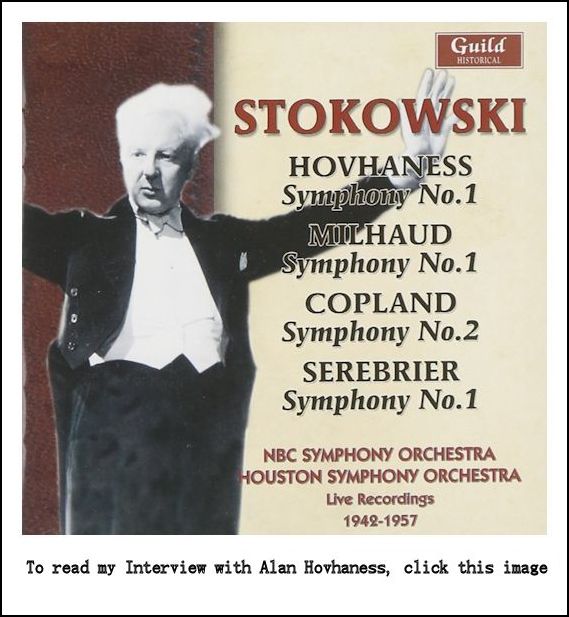

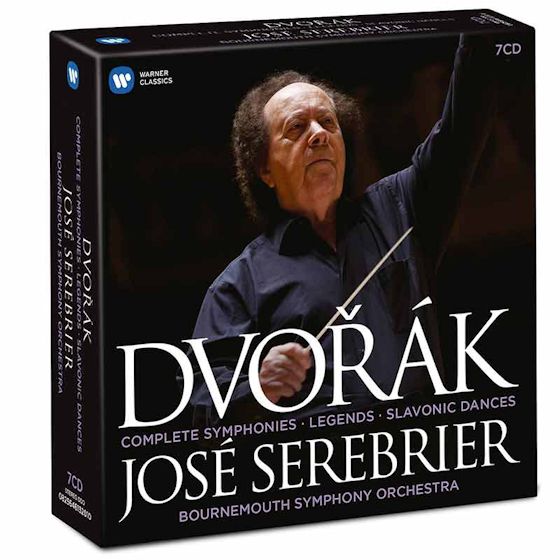

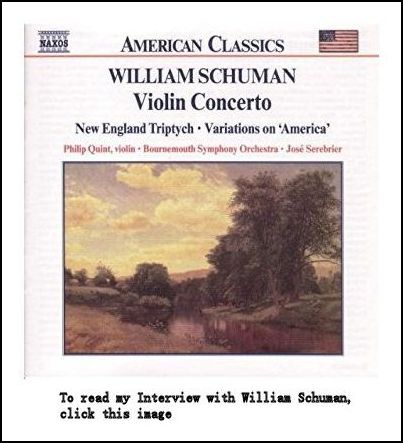

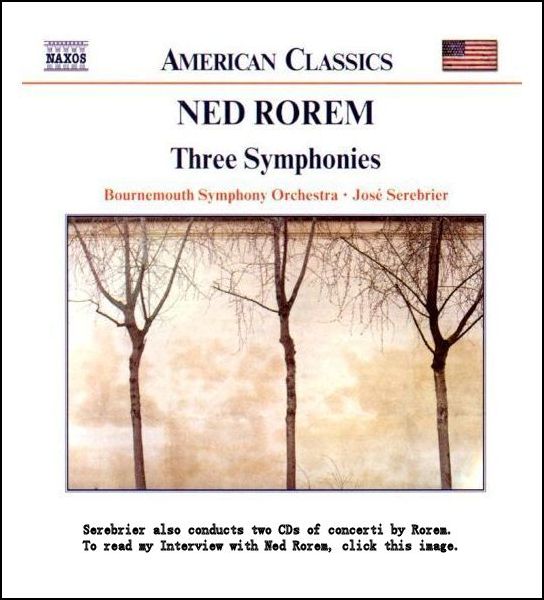

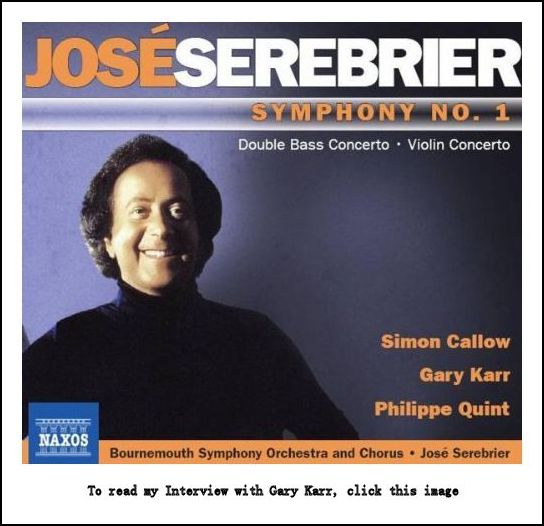

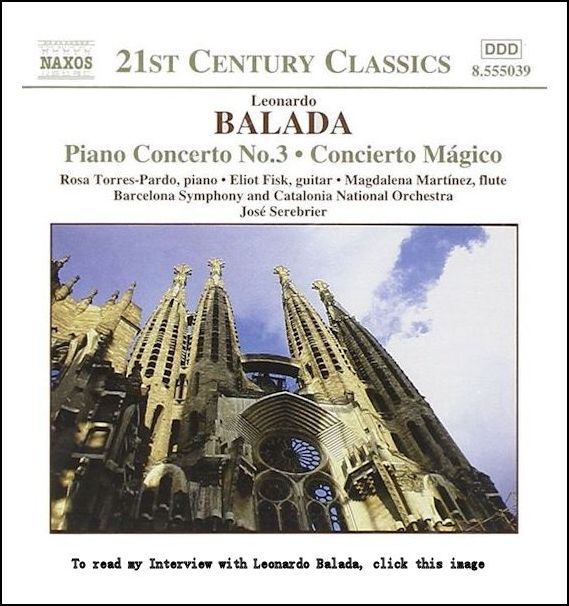

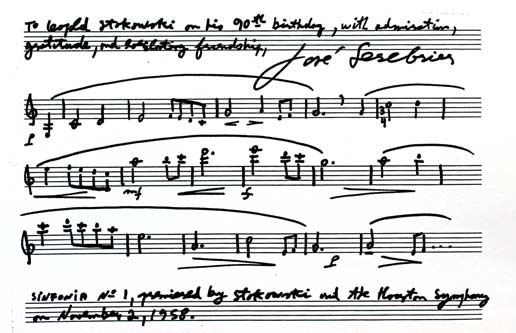

and composer. He is one of the most recorded conductors of his generation. Serebrier was born in Montevideo to Russian and Polish parents of Jewish extraction. He first conducted an orchestra at the age of eleven, while at school. The school orchestra toured the country, which meant he was able to notch up over one hundred performances within four years. He graduated from the Municipal School of Music in Montevideo at fifteen, having studied violin, solfege, and Latin American folklore. Subsequently, he studied counterpoint, fugue, composition and conducting with Guido Santórsola, and piano with his wife, Sarah Bourdillon Santórsola. The National Orchestra, known as SODRE, announced a composition contest. Within two weeks, Serebrier had composed his Legend of Faust overture. It won, but to his huge disappointment he was not allowed to conduct it, because he was only fifteen. The premiere was given to Eleazar de Carvalho, who later that same year became his conducting teacher at Tanglewood, the Boston Symphony Orchestra's summer home. He was awarded a United States State Department Fellowship to study at the Curtis Institute of Music, with Vittorio Giannini. Later he studied with Aaron Copland at Tanglewood, and with Pierre Monteux. His First Symphony, written at the age of 17, was premiered by Leopold Stokowski, as the last minute substitute for the Ives Fourth Symphony, which proved still unplayable at the time. Another recording of the Serebrier work was released by Naxos, with the composer conducting the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra. Serebrier's New York conducting debut with the American Symphony

Orchestra was at Carnegie Hall in 1965. At the time, Ives' Fourth Symphony

had been considered so difficult that it was performed using three

conductors at its premiere in 1965, almost 50 years after its composition.

Stokowski, Serebrier and a third conductor (David Katz) performed it

this way. A few years later Serebrier conducted it on his own. He made

his recording debut with the work, and Hi-Fi News and Record Review

wrote of it: "This ... must surely count as one of the great achievements

of the gramophone".

Serebrier married American soprano Carole Farley in 1969. They have made a number of recordings together. Serebrier's Third Symphony and his Fantasia for Strings

are amongst his most popular works. His style is energetic, colorful

and melodic. One of his most unusual works is Passacaglia and Perpetuum

Mobile for Accordion and Chamber Orchestra. His music is published mainly

by Peermusic New York and Hamburg, and also by Peters Edition, Universal

Edition Vienna, Hal Leonard, Kalmus, Boosey & Hawkes. His works have

been recorded on various labels.

|

BD: Especially in works like Till

Eulenspiegel, I would think the conductor would absolutely have to

have a sense of humor before he can step onto the podium.

BD: Especially in works like Till

Eulenspiegel, I would think the conductor would absolutely have to

have a sense of humor before he can step onto the podium. BD: Is this partly due in fact to there are all

these little round flat things that get sold in stores?

BD: Is this partly due in fact to there are all

these little round flat things that get sold in stores?  BD: Does that put a little more onus

on others to play your music?

BD: Does that put a little more onus

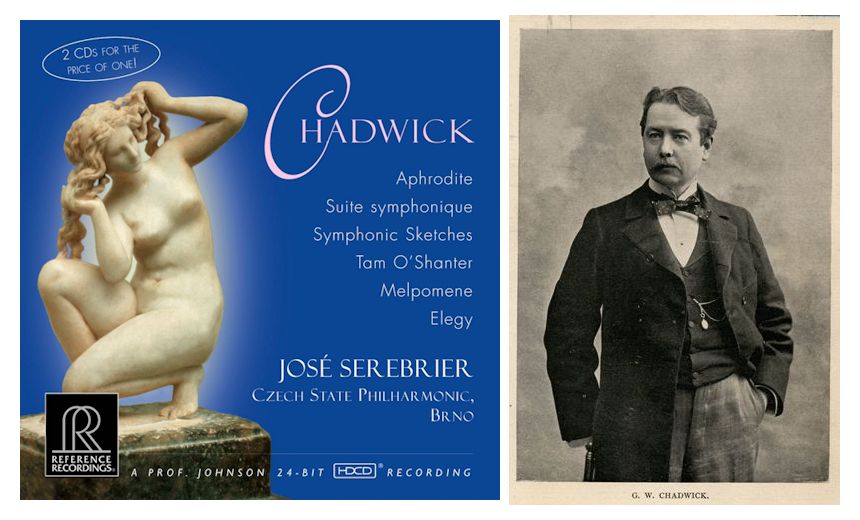

on others to play your music? George Whitefield Chadwick (November 13,

1854 – April 4, 1931) was an American composer. Along with John Knowles

Paine, Horatio Parker, Amy Beach, Arthur Foote, and Edward MacDowell,

he was a representative composer of what is called the Second New England

School of American composers of the late 19th century—the generation before

Charles Ives. Chadwick's works are influenced by the Realist movement

in the arts, characterized by a down-to-earth depiction of people's lives.

Many consider his music to portray a distinctively American style. His

works included several operas, three symphonies, five string quartets,

tone poems, incidental music, songs and choral anthems.

|

JS: All the time, yes. Although I prefer

concerts because they’re live and you have an audience to play for and

it’s not in a dead studio, records are very important to me because they

do get to a very wide audience, especially thanks to your station. You

do a concert, and the maximum is a few thousand people. A record

can be hopefully heard by many more than that.

JS: All the time, yes. Although I prefer

concerts because they’re live and you have an audience to play for and

it’s not in a dead studio, records are very important to me because they

do get to a very wide audience, especially thanks to your station. You

do a concert, and the maximum is a few thousand people. A record

can be hopefully heard by many more than that.  JS: Absolutely. It is the

beginning, and it’s not the most important factor... although it helps

the general feeling if the notes are all there. It’s definitely a

basis from which to depart. About five years ago I was on the jury

for a piano competition, and it was named after the corporation that sponsored

it, which was the Xerox Corporation. I’m sorry for the pianists that

won it because they’re called the Xerox Pianists. [Both laugh] They

will sponsor any kind of competition, but you can imagine a painter’s competition.

Being the Xerox painter would be worse. I’ve been on

many juries, and I am a kind juror, but this was unfortunate. It

was very well named because all the pianists were playing literally like

photocopies of each other. That’s partially the problem in the last

ten years or so because they listen to each other’s records, and they try

to imitate. The great personality is seldom found these days.

JS: Absolutely. It is the

beginning, and it’s not the most important factor... although it helps

the general feeling if the notes are all there. It’s definitely a

basis from which to depart. About five years ago I was on the jury

for a piano competition, and it was named after the corporation that sponsored

it, which was the Xerox Corporation. I’m sorry for the pianists that

won it because they’re called the Xerox Pianists. [Both laugh] They

will sponsor any kind of competition, but you can imagine a painter’s competition.

Being the Xerox painter would be worse. I’ve been on

many juries, and I am a kind juror, but this was unfortunate. It

was very well named because all the pianists were playing literally like

photocopies of each other. That’s partially the problem in the last

ten years or so because they listen to each other’s records, and they try

to imitate. The great personality is seldom found these days.  JS: No, you have to steal the time. This may

sound irreverent to people that do not understand the limitations of time,

but I do much of my composing on long flights to Australia, and across

the Ocean to Europe and to South America and to South Africa.

It’s a perfect time to write music because unless there is a great movie

on the plane there are no distractions.

JS: No, you have to steal the time. This may

sound irreverent to people that do not understand the limitations of time,

but I do much of my composing on long flights to Australia, and across

the Ocean to Europe and to South America and to South Africa.

It’s a perfect time to write music because unless there is a great movie

on the plane there are no distractions.  BD: Are there times when performers take your pieces

and find things that you didn’t even know you’d hidden in the score?

BD: Are there times when performers take your pieces

and find things that you didn’t even know you’d hidden in the score?

BD: But I assume you need that foundation.

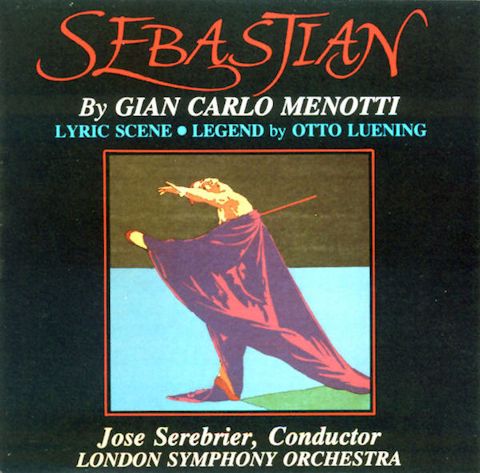

BD: But I assume you need that foundation. JS: I never thought of my life as following a career.

I meet people around the world who tell me my career is going so great,

and I’m always surprised because I never planned it as a career.

I have some distinguished colleagues who make five-year plans, and one-year

plans, but I never made a plan I’m sorry to say. It is more or less

a façade, partially because I’m both a composer and a conductor,

and therefore some things take priority in different times of my life.

For example, when George Szell invited me to go to Cleveland and to be Assistant

Conductor, I had won a competition in Baltimore, an American conductors’

award, together with Jimmy Levine. Szell was on the jury, and invited

us both to join him in Cleveland as assistants. Levine accepted,

as he had just graduated from Juilliard, and I didn’t accept because I

was working with Stokowski. Since Stokowski was already in his middle

to late eighties, I didn’t want to miss any time, and though I admired

Szell very much, I thought this was a greater opportunity not to miss,

and so I said no. Also Szell had too many assistants at the time.

With Stokowski, I was the Associate Conductor. A year later Szell

came back to me and made me an offer I had to accept. It was a special

grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to be composer-in-residence.

So you see, careers sometimes change with unexpected terms that you don’t

plan. If you plan it, it’s great, and you live up to it. So then

I became composer-in-residence of the Cleveland Orchestra until the music

critic of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Wilma Salisbury, wrote a whole-page

article denouncing me for not spending enough time composing, and going all

over the world conducting. “He is conducting

the London Symphony in London, the Paris Orchestra, and in Australia.

When does he spend time in Cleveland where we pay him to compose?”

So immediately I wrote a harp concerto which I dedicated to her.

[Laughs] She has since given me great reviews. I went back to

Cleveland a few years later to conduct a concert, and she gave me an embarrassingly

good review. Actually she made me compose, so you see things happen

that change your life, and you have to go with it.

JS: I never thought of my life as following a career.

I meet people around the world who tell me my career is going so great,

and I’m always surprised because I never planned it as a career.

I have some distinguished colleagues who make five-year plans, and one-year

plans, but I never made a plan I’m sorry to say. It is more or less

a façade, partially because I’m both a composer and a conductor,

and therefore some things take priority in different times of my life.

For example, when George Szell invited me to go to Cleveland and to be Assistant

Conductor, I had won a competition in Baltimore, an American conductors’

award, together with Jimmy Levine. Szell was on the jury, and invited

us both to join him in Cleveland as assistants. Levine accepted,

as he had just graduated from Juilliard, and I didn’t accept because I

was working with Stokowski. Since Stokowski was already in his middle

to late eighties, I didn’t want to miss any time, and though I admired

Szell very much, I thought this was a greater opportunity not to miss,

and so I said no. Also Szell had too many assistants at the time.

With Stokowski, I was the Associate Conductor. A year later Szell

came back to me and made me an offer I had to accept. It was a special

grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to be composer-in-residence.

So you see, careers sometimes change with unexpected terms that you don’t

plan. If you plan it, it’s great, and you live up to it. So then

I became composer-in-residence of the Cleveland Orchestra until the music

critic of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Wilma Salisbury, wrote a whole-page

article denouncing me for not spending enough time composing, and going all

over the world conducting. “He is conducting

the London Symphony in London, the Paris Orchestra, and in Australia.

When does he spend time in Cleveland where we pay him to compose?”

So immediately I wrote a harp concerto which I dedicated to her.

[Laughs] She has since given me great reviews. I went back to

Cleveland a few years later to conduct a concert, and she gave me an embarrassingly

good review. Actually she made me compose, so you see things happen

that change your life, and you have to go with it.

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 16, 1998. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.