A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

BD:

Was there a time when Wotan was a good guy?

BD:

Was there a time when Wotan was a good guy? BD: Is Wotan fun to sing?

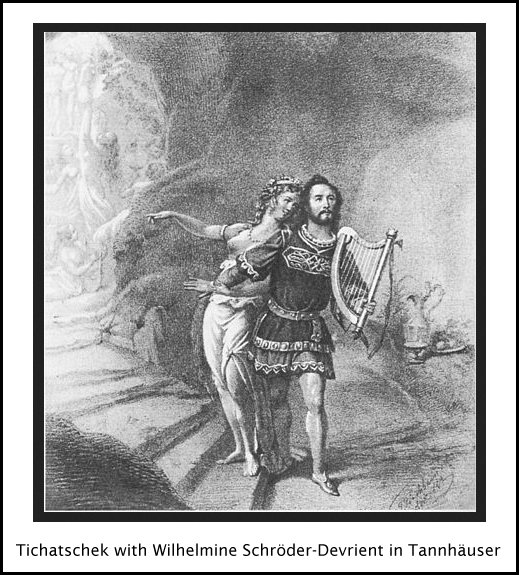

BD: Is Wotan fun to sing?| Josef Aloys Tichatschek (11 July

1807 – 18 January 1886), originally Tichaček, was a Bohemian opera singer

highly regarded by Richard Wagner. He created the title roles in Wagner's

operas Rienzi and Tannhäuser. As the first of the great Wagnerian tenors,

he effectively was the original Heldentenor, although it is unlikely that

his voice was as powerful as that of 20th-century Heldentenors such as Lauritz

Melchior or Jon Vickers,

given the smaller volume of sound produced by orchestras in his heyday. Wagner referred to his voice as "ein Wunder von männlich schönem Stimmorgan." Berlioz, referring to a Dresden concert in 1843, wrote: 'Tichatschek, the tenor, has a pure and touching voice, which becomes very powerful when animated by the dramatic action. His style of singing is simple and in good taste; he is a consummate reader and musician, and undertook the tenor solo in the Sanctus (from Berlioz's Requiem) at first sight, without reserve, or affectation, or pretension.' The singer's contemporary, Sincerus, emphasised that he was equally effective in works requiring romantic softness and sweetness of tone, having a very natural vocal production. His intonation and diction were above suspicion, but his 'coluratura' was imperfect and his acting sometimes a little awkward.  The title role of Rienzi was written for Tichatschek, and was exactly suited

to his robust and dramatic voice. He learnt the part by singing it at sight

from score during rehearsals, rather than by home study, with the result that

he brought little reflection or dramatic intelligence to bear upon it. The

first performance lasted about six hours and caused great excitement. Wagner

instructed that cuts should be made, but Tichatschek refused saying it was

'too heavenly'. After six performances it was decided to give the opera over

two nights, but people objected to paying twice, and so the cuts were made.

The work did not meet the same success in Hamburg and Berlin because Tichatschek

did not appear there, and he was the only one whose voice and presence were

then adequate for the role. Berlioz wrote: 'Tichatschek is gracious, impassioned,

brilliant, heroic, and entrancing in the role of Rienzi, in which his fine

voice and large fiery eyes are of inestimable service... I remember a beautiful

prayer sung in the last act.'

The title role of Rienzi was written for Tichatschek, and was exactly suited

to his robust and dramatic voice. He learnt the part by singing it at sight

from score during rehearsals, rather than by home study, with the result that

he brought little reflection or dramatic intelligence to bear upon it. The

first performance lasted about six hours and caused great excitement. Wagner

instructed that cuts should be made, but Tichatschek refused saying it was

'too heavenly'. After six performances it was decided to give the opera over

two nights, but people objected to paying twice, and so the cuts were made.

The work did not meet the same success in Hamburg and Berlin because Tichatschek

did not appear there, and he was the only one whose voice and presence were

then adequate for the role. Berlioz wrote: 'Tichatschek is gracious, impassioned,

brilliant, heroic, and entrancing in the role of Rienzi, in which his fine

voice and large fiery eyes are of inestimable service... I remember a beautiful

prayer sung in the last act.'Tichatschek rehearsed Tannhäuser with Wagner as it was being written, in company with his Elisabeth, the mezzo-soprano Johanna Jachmann-Wagner. It is said that when they had finished going through the Act 3 recitative for the first time, he and Wagner embraced each other in tears. His voice, however, did not hold up well during the second and third acts of the first performance, and the repetition (for the next day) had to be postponed owing to his hoarseness, and when it did appear many cuts were made in the part. It is said that the virtual failure of Tannhäuser was owing to Tichatschek's inability to grasp the dramatic meaning of the work. This had been foreseen by Schröder-Devrient, and his lack of psychological subtlety, of dramatic insight and detailed study, soon became painfully apparent. Above all, Tichatschek's failure to bring off the dramatic meaning of the extended passage in the finale of Act 2 ('Erbarm' dich mein!') resulted in the need for this to be cut, much to Wagner's sorrow. In 1852-3 Wagner went over this ground in his essay On the Performing of Tannhäuser, but the cuts had become so customary that he had to explain the matter afresh (and with no happier outcome) to Niemann who was to sing the role at Paris in 1861. He and Johanna Jachmann-Wagner remained friends for many years: she was Valentine opposite his Raoul in Les Huguenots at Dresden in 1846. They appeared together in Tannhäuser at Dresden again in 1858. Tichatschek was also a distinguished Lohengrin. The Dresden management presented Lohengrin in Wagner's absence during 1858-1859, when Tichatschek made an urgent plea for them to send Wagner (then in exile) a honorarium of 50 louis d'or - which they did. In 1867, when planning a production of Lohengrin for Ludwig II, Wagner recommended the almost 60-year-old Tichatschek for the role, saying that his Lohengrin had been the one really good thing the tenor had done, assuring the King that, while his singing and declamation in the role suggested a painting by Dürer, his appearance and gestures were like a Holbein. Wagner was delighted with his singing at the rehearsal, but Ludwig, thoroughly disillusioned by the singer's less-than-ideal appearance, forbade him to be employed for the performances, resulting in a rift between the King and the composer. Tichatschek first told Wagner of the young Karlsruhe tenor who was to become his own successor, and more-than-successor, Ludwig Schnorr von Carolsfeld, in 1856. Von Carolsfeld sang for Wagner and also created the role of Tristan in 1865 shortly before his own untimely death at age 29. |

|

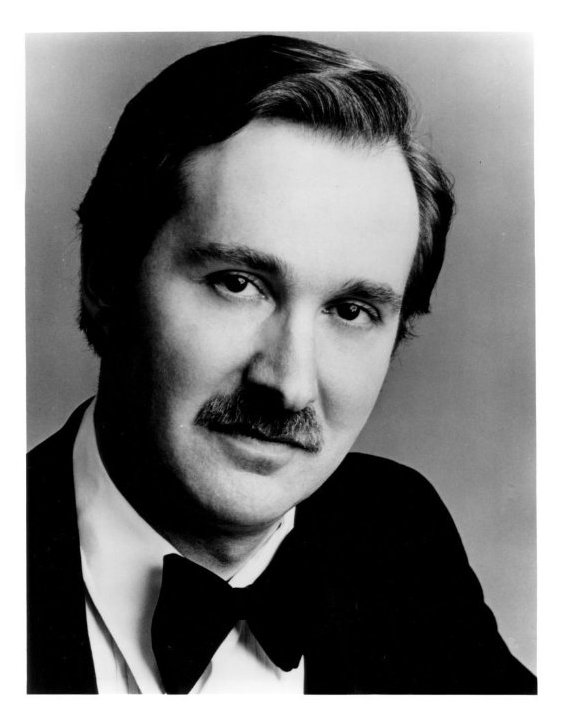

Two snippets from reviews which

appeared in The New York Times .

. . . .

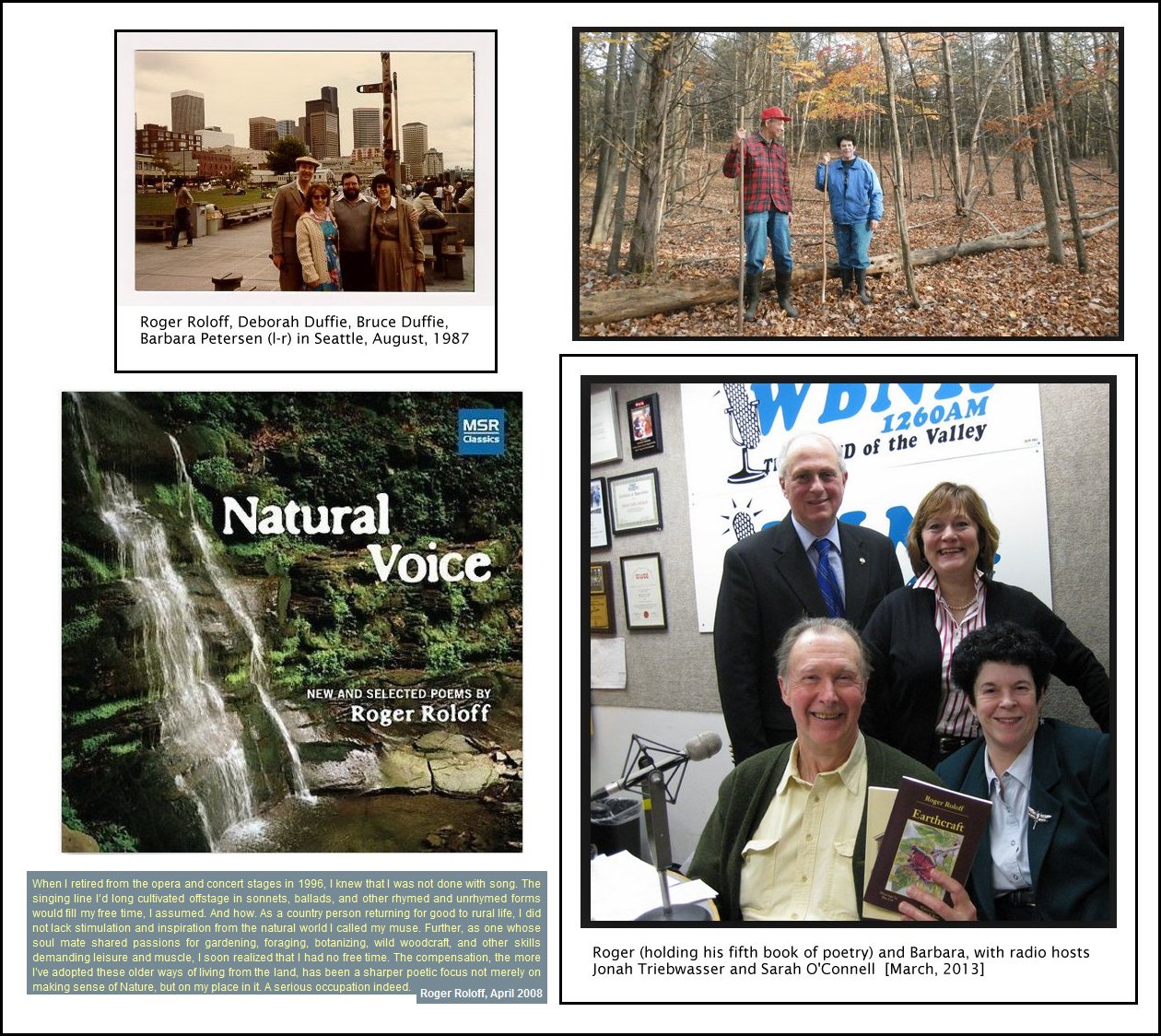

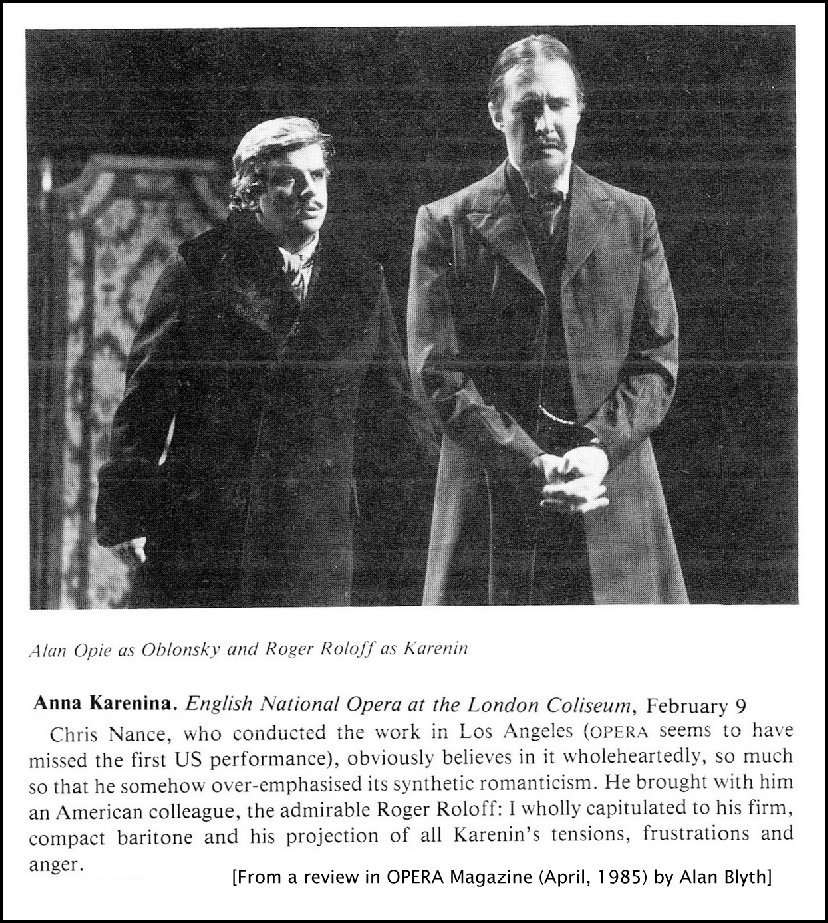

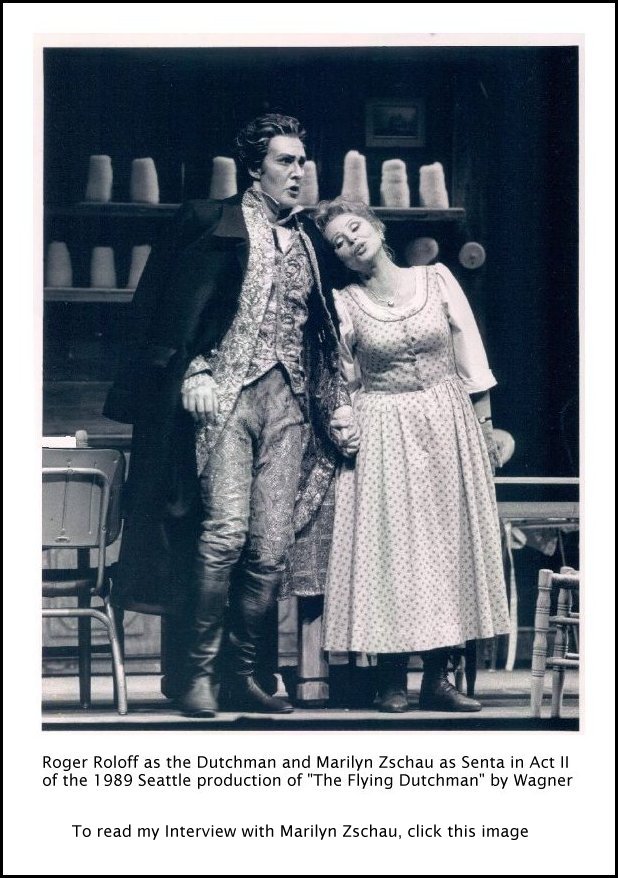

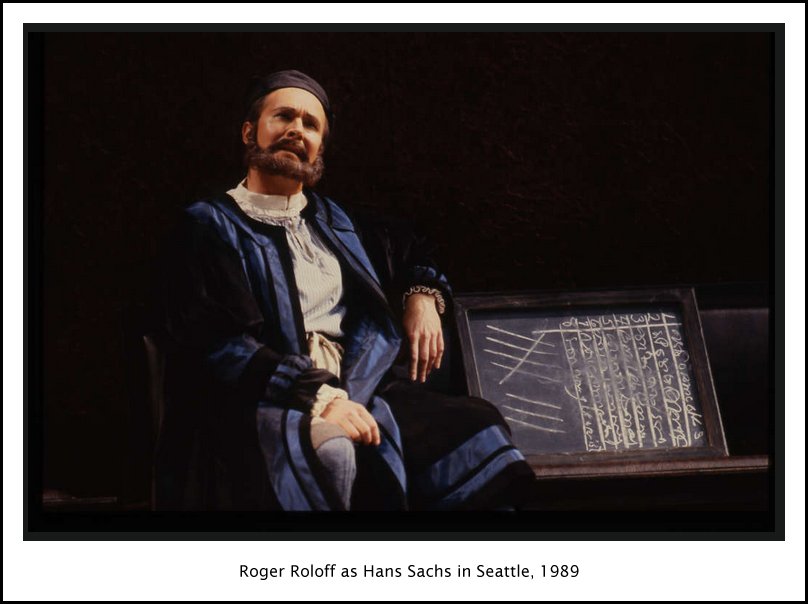

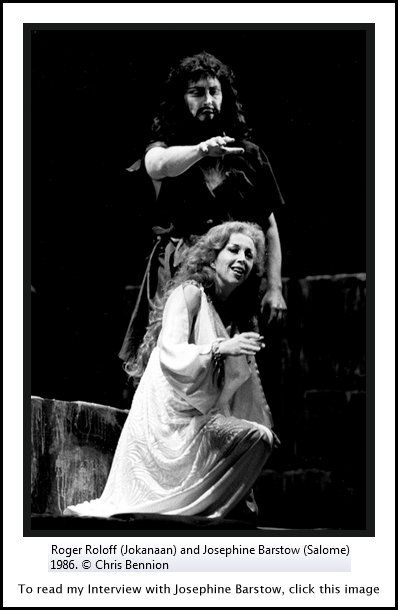

[From a review of "Guntram" performed by the Opera Orchestra of New York.] By Donal Henahan, NYT 1/21/83 Standing out in the large cast were Peter Wimberger as Guntram's friend Friedhold, Roger Roloff as the old Duke and Peter Kararas as the Fool. Geraldine Decker, as an Old Woman, poured out an idiomatic Strauss-Wagner sound and gave a spunky account of her small part. * *

* * *

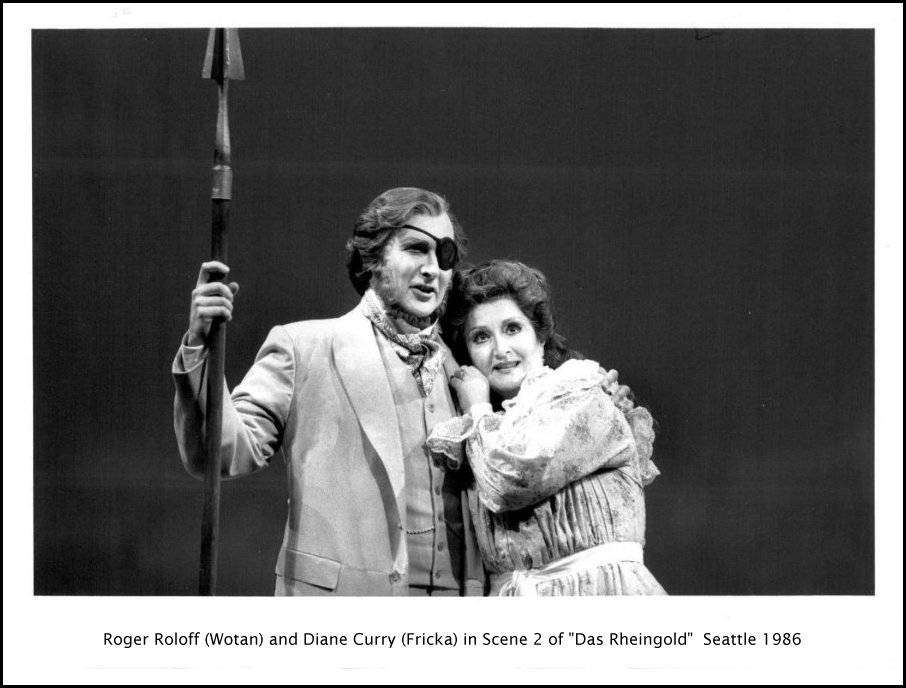

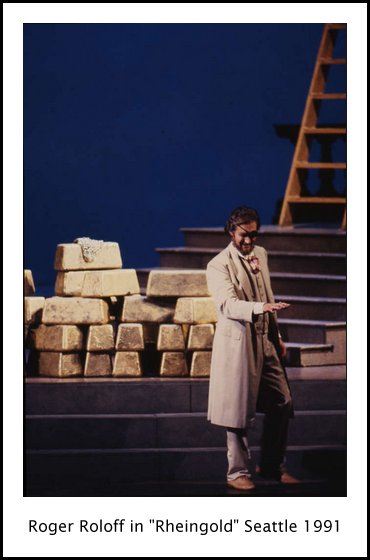

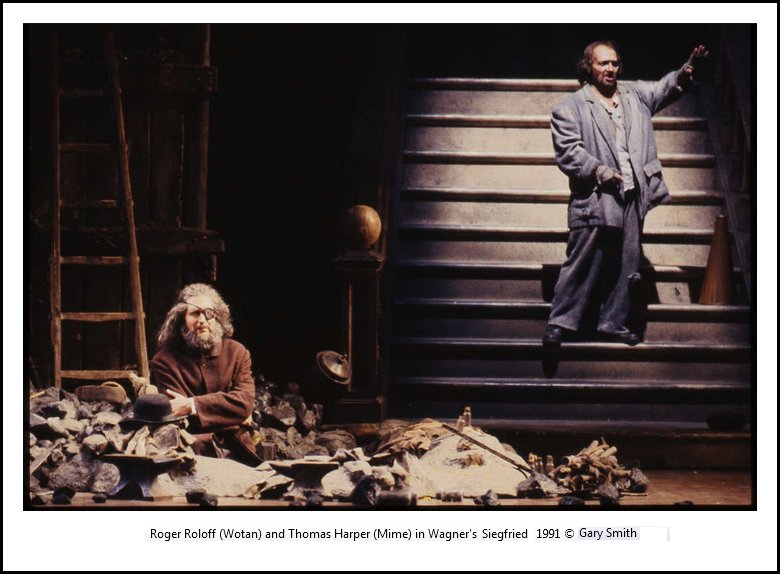

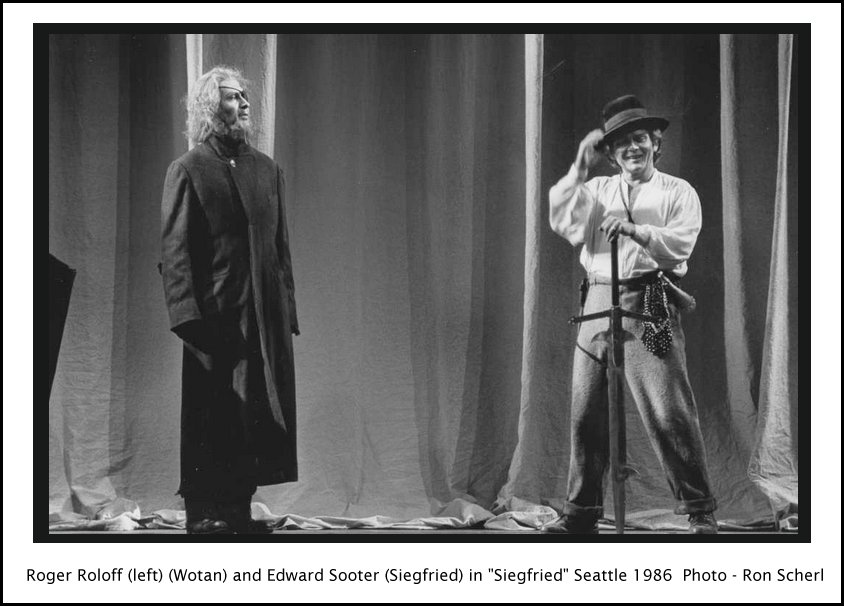

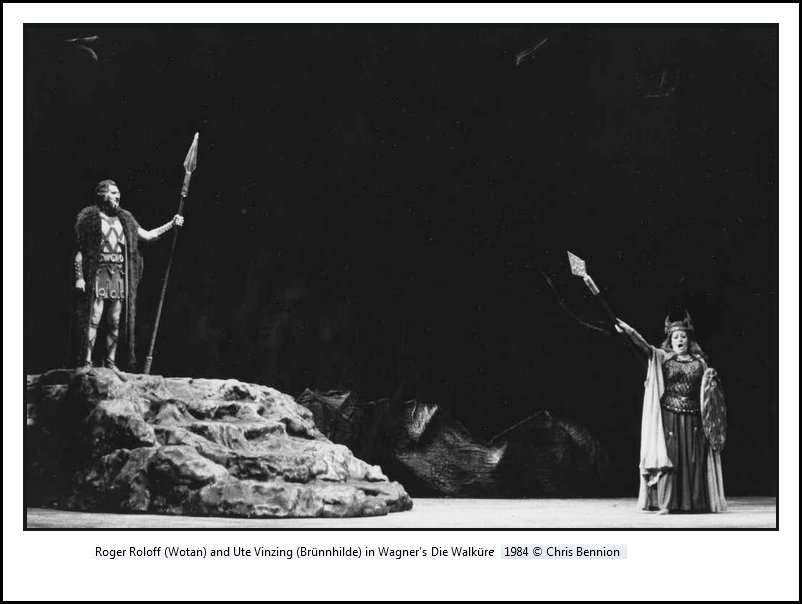

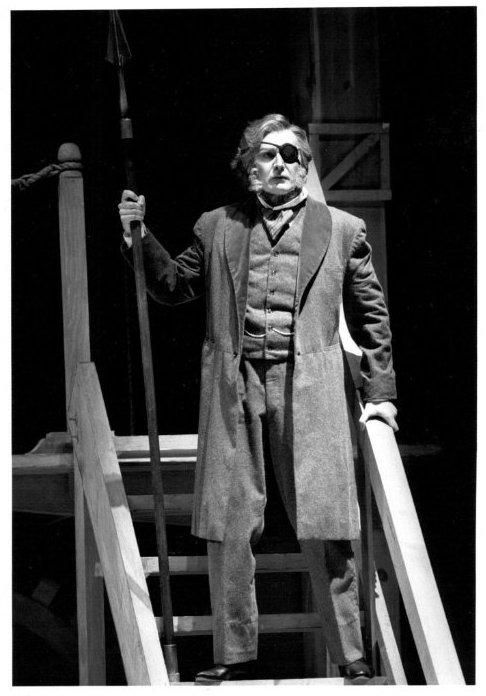

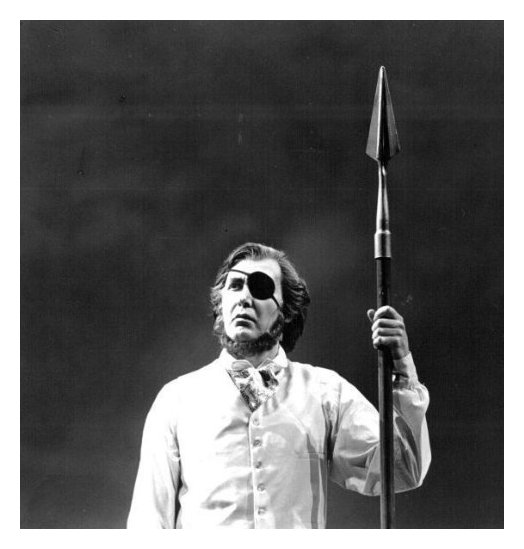

[From a review of the "Ring" in Seattle.] By John Rockwell, NYT 8/10/86 Musically, there was much to admire, although the Seattle company is not in a position to afford a top-level international cast. The conductor was to have been Armin Jordan, best known for his conducting and acting of Amfortas in Hans-Jurgen Syberberg's film of ''Parsifal.'' Mr. Jordan led the ''Walküre'' last year to general acclaim, but bowed out this summer with a back problem. He was replaced by Manuel Rosenthal, much admired for his work in the French repertory but here leading his first ''Ring'' - at the age of 82. Mr. Rosenthal did many lovely things, especially in lyrical moments. The cast was variable, though hardly ever less than competent. The standout was Roger Roloff, light of voice but really magisterial in timbre, phrasing and intelligence as Wotan. Julian Patrick's sure Alberich and James Patterson's cavernous Fafner were also worthy of special praise. Other fine performances came from Emile Belcourt, musically cavalier but theatrically vivid as Loge; Hubert Delamboye, a solid Mime; Johanna Meier, in full, firm voice as Sieglinde; Warren Ellsworth, sometimes iffy of rhythm and pitch but a sympathetic Siegmund, and John Macurdy, a strong Hunding and Hagen. Linda Kelm, singing her first complete Brunnhilde, has all the vocal heft and technique needed but seemed dramatically blank and visually awkward. Edward Sooter, as Siegfried, has vocal weight but little else, lacking nearly all the requisite poetry. |

BD: What else do you look for in deciding whether

you will accept or reject a part that you are offered?

BD: What else do you look for in deciding whether

you will accept or reject a part that you are offered? BD:

But you had good success?

BD:

But you had good success?

BD: But you are still giving enough?

BD: But you are still giving enough? RR: This is something that I’m used to in Germany

more than here. It would be nice to have a prompter for the wings because

it is just humongous undertaking, but they haven’t done it in Seattle, and

they paid the price in some earlier Rings

where people would just get lost.

RR: This is something that I’m used to in Germany

more than here. It would be nice to have a prompter for the wings because

it is just humongous undertaking, but they haven’t done it in Seattle, and

they paid the price in some earlier Rings

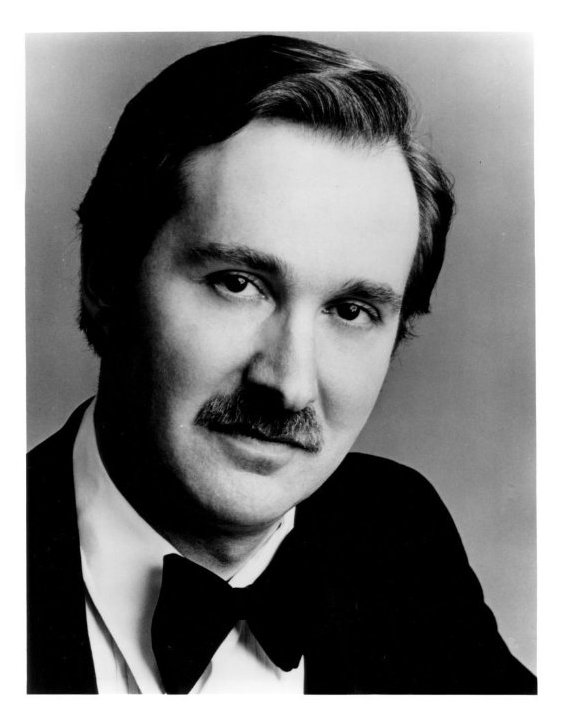

where people would just get lost.This conversation was recorded in Seattle, Washington, on August 6,

1987. This transcription was made and much of it was published in Wagner News in February, 1989. It

has now been completed and re-edited, the introduction, pictures, and links

have been added, and it has been posted on this website early in 2016.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.