|

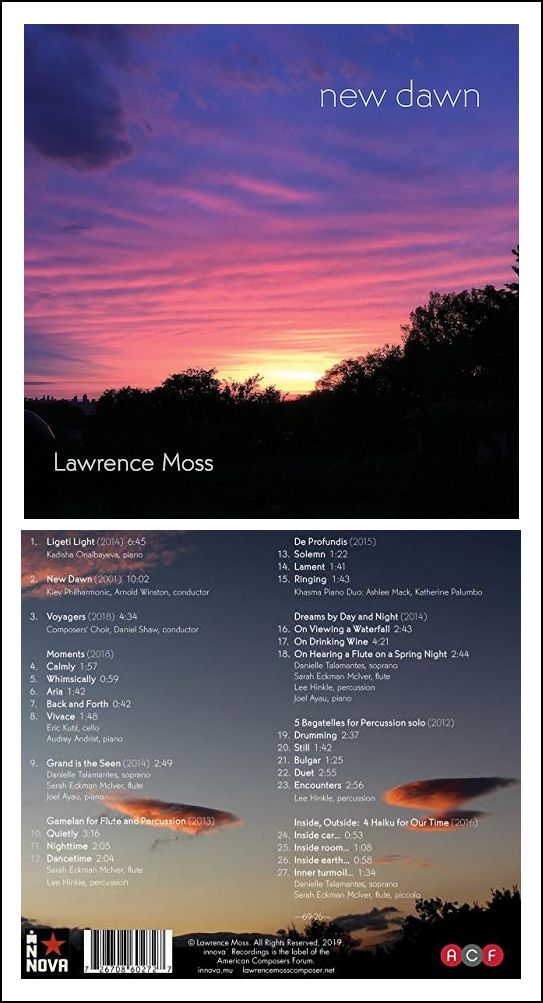

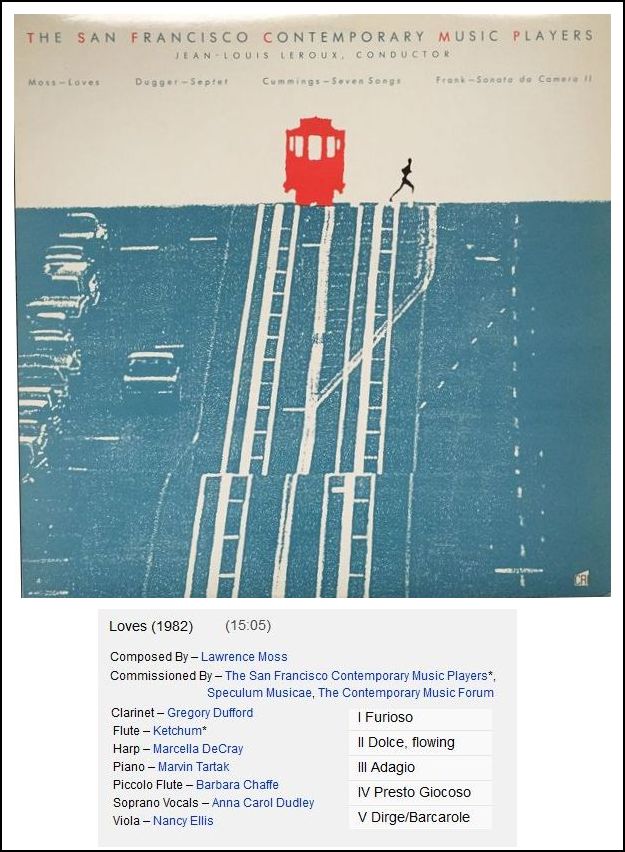

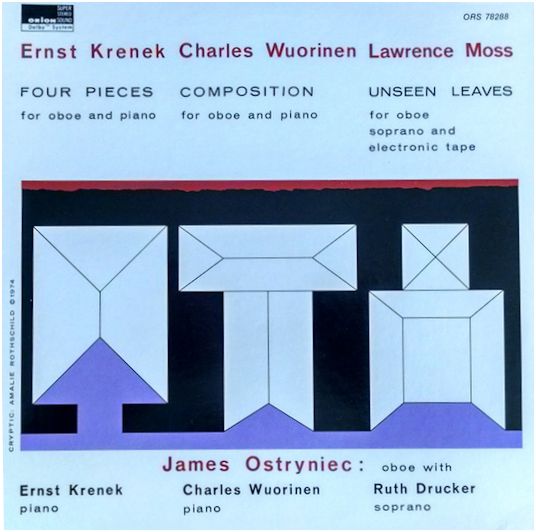

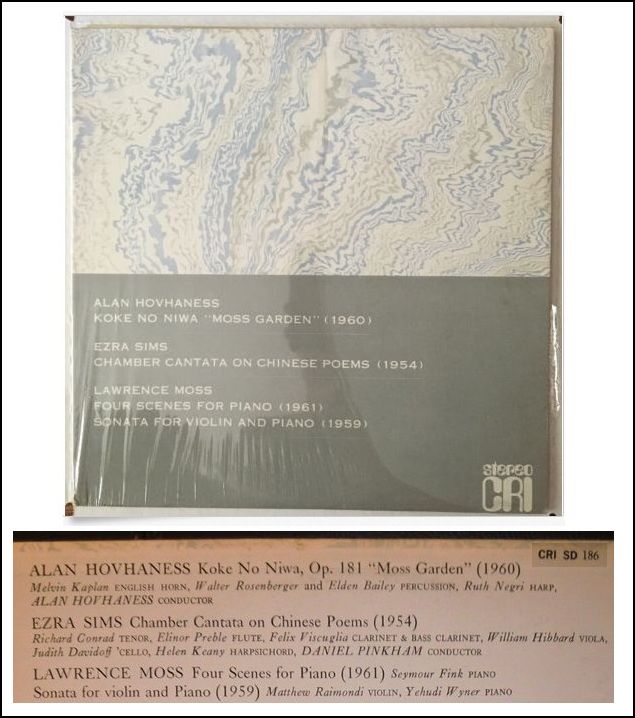

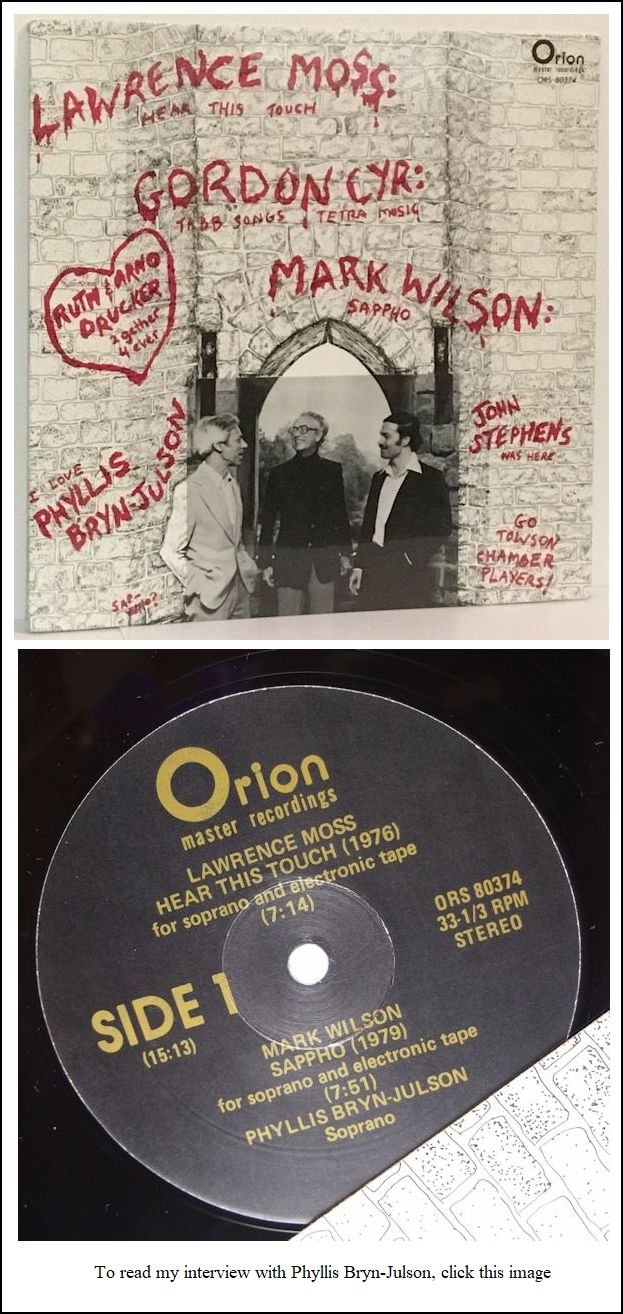

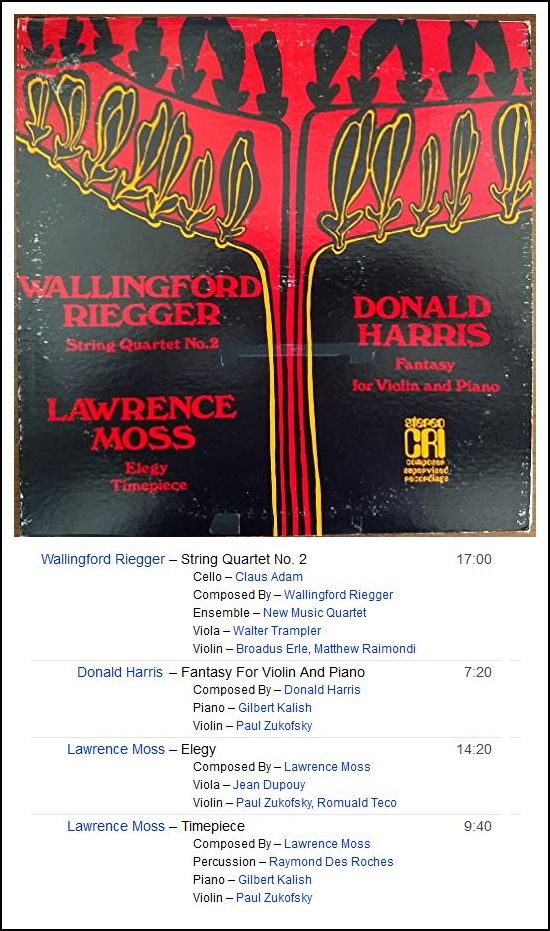

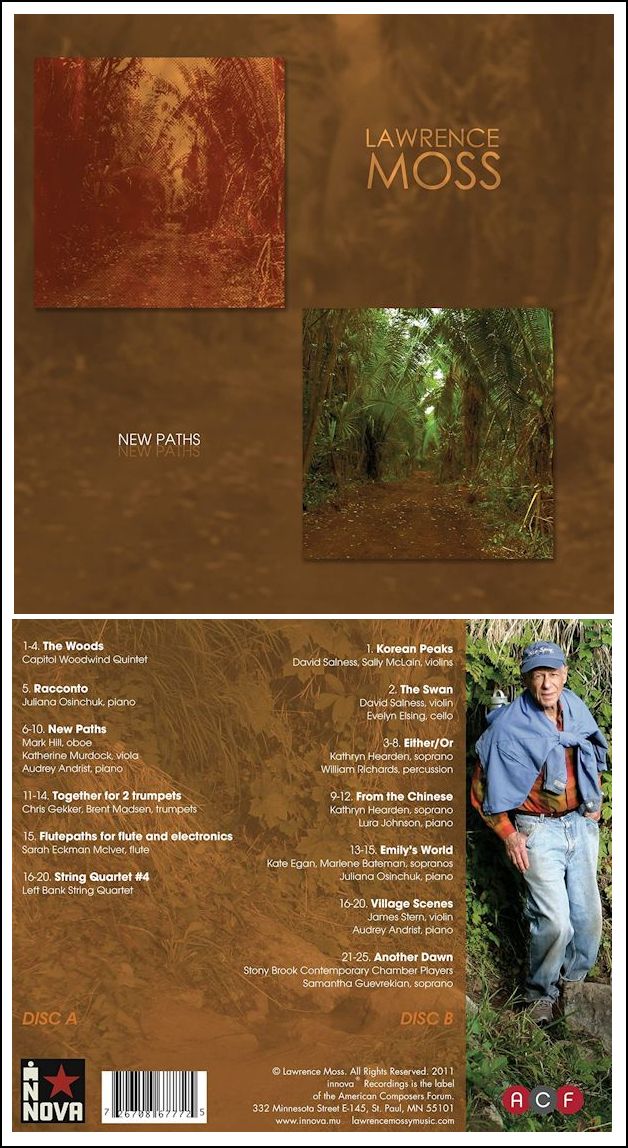

Lawrence Kenneth Moss (born November 18, 1927 in Los Angeles, California) is an American composer of contemporary classical music. He holds a B.A. degree from the University of California, Los Angeles, an M.A. from the Eastman School of Music, and a Ph.D. in music composition from the University of Southern California, where his instructors included Leon Kirchner and Ingolf Dahl. He has taught at Mills College, Yale University (1960-1968), and the University of Maryland, College Park (since 1969). His notable students include Jeffrey Mumford, Liviu Marinescu, and Susan Cohn Lackman. He has received two Guggenheim Fellowships (1959 and 1968), a Fulbright Scholarship, and four grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. Moss has composed operatic, instrumental, and electronic music. His music is published by Theodore Presser, Association for the Promotion of New Music (A.P.N.M.), McGinnis & Marx, Alfred Publishing Co., Roncorp Inc., Northeastern Music Programs, and Seesaw Music Corp. His music has been recorded on the CRI, Desto, Opus One, Albany, Capstone, Orion, EMF, Spectrum, Advance, and AmCam labels. |

As always, names which are links refer to my interviews

elsewhere on this website.

As always, names which are links refer to my interviews

elsewhere on this website. BD: Do you work on just one piece at

a time, or do you have a couple of things going?

BD: Do you work on just one piece at

a time, or do you have a couple of things going? Moss: Yes. I like to be performed

on concerts that would include the great figures, such as Stravinsky,

Bartók, Schoenberg, Webern, any of these people. These

are the ideal repertoire for contemporary music. I’m not so sure

that we do composers a favor by putting them on programs of exclusively

music written since 1980 or 1970, because it all can tend to sound very

much alike. There’s not that much great music, so I like to be on

concerts where there are ‘masterpieces’,

pieces that are superbly written which will anchor the program.

Moss: Yes. I like to be performed

on concerts that would include the great figures, such as Stravinsky,

Bartók, Schoenberg, Webern, any of these people. These

are the ideal repertoire for contemporary music. I’m not so sure

that we do composers a favor by putting them on programs of exclusively

music written since 1980 or 1970, because it all can tend to sound very

much alike. There’s not that much great music, so I like to be on

concerts where there are ‘masterpieces’,

pieces that are superbly written which will anchor the program.|

The Brute was written during my first Guggenheim Fellowship and is dedicated to the Guggenheim Foundation. It received its premiere at the Yale University Norfolk Summer School in 1960 under the baton of Gustav Meier, with Jan de Gaetani in the role of Mrs. Popov. Under the sponsorship of the New Haven Opera Society (Herta Glaz, Director) it

received a grant for performances in the New Haven Public Schools, where

it was paired with the stage version of Chekov's play, The Bear

on which Erich Bentley based his libretto. The Brute was chosen to represent the United States at the 20th International Youth Festival held in Bayreuth, Germany in 1970. It received its European premiere there in the Bayreuth Staatsopernhaus. It has been performed in New York City and elsewhere in the United

States. A videotape of its premiere in Chicago, under the baton of

Ralph Shapey, was

broadcast by CBS television in 1964. == From the composer's official website |

|

Le Corbusier was commissioned by Philips to present a pavilion at

the 1958 World Fair and insisted (against the sponsors' resistance)

on working with Varèse, who developed his Poème électronique

for the venue, where it was heard by an estimated two million people.

Using 400 speakers separated throughout the interior, Varèse created

a sound and space installation geared towards experiencing sound as it

moves through space. Received with mixed reviews, this piece challenged

audience expectations and traditional means of composing, breathing life

into electronic synthesis and presentation. |

BD: You wrote an article about fifteen

years ago, On Writing a Libretto. I have not read the

article, but do you still subscribe to the theories that you put forth

at that time?

BD: You wrote an article about fifteen

years ago, On Writing a Libretto. I have not read the

article, but do you still subscribe to the theories that you put forth

at that time? Moss: Yes, but for me, recording

is not a substitute for going to concerts. I’m of that generation

that feels there is something about the excitement of seeing performers,

going to rehearsals, and studying the score, which is important.

These kids have lots of records, but very few scores. This is just

the opposite of my library, which is lots of scores and very few records.

That’s typical of my generation. It was certainly true

of my teachers. I love to look at scores. Certainly, I

value a recording to refresh my mind, but I find the most exciting thing

is looking at the score. I agree with what Roger Sessions once

said, and that is once you heard the recording, the next time you

can predict what’s going to happen. It’s lost that excitement.

Although, I must say, driving around and listening to the radio

shows like yours, I am sometimes bowled over, by recordings I didn’t

know about. It’s very exciting, particularly when I tune in during

the middle, and don’t know who’s doing it. I just wonder, who

could be doing this. It’s a very exciting thing, and I love to turn

on the radio, and imagine. At first, I’ll guess what it is,

and then listen to it and see what’s going on in the performance.

Moss: Yes, but for me, recording

is not a substitute for going to concerts. I’m of that generation

that feels there is something about the excitement of seeing performers,

going to rehearsals, and studying the score, which is important.

These kids have lots of records, but very few scores. This is just

the opposite of my library, which is lots of scores and very few records.

That’s typical of my generation. It was certainly true

of my teachers. I love to look at scores. Certainly, I

value a recording to refresh my mind, but I find the most exciting thing

is looking at the score. I agree with what Roger Sessions once

said, and that is once you heard the recording, the next time you

can predict what’s going to happen. It’s lost that excitement.

Although, I must say, driving around and listening to the radio

shows like yours, I am sometimes bowled over, by recordings I didn’t

know about. It’s very exciting, particularly when I tune in during

the middle, and don’t know who’s doing it. I just wonder, who

could be doing this. It’s a very exciting thing, and I love to turn

on the radio, and imagine. At first, I’ll guess what it is,

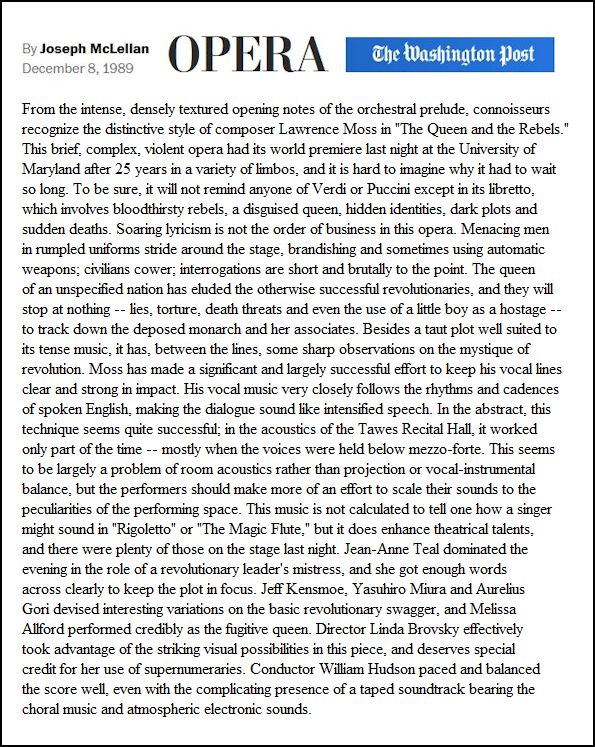

and then listen to it and see what’s going on in the performance. Moss: They write musical reviews,

but the music critic can be pretty a powerful influence actually.

Here in the Washington Post, we have Joe McLellan, who’s a very

sweet man. [Notice that this interview was held before the production

which he reviewed!] He’s a very bright man, and he writes

practically always very enthusiastically about new music. He’s

consistently that way. He’s not critical. On the other

hand, he’s enthusiastic, and he’s been very helpful in getting people to

come to things they might not come to otherwise. He probably sees

himself as a patron of a newer kind of music.

Moss: They write musical reviews,

but the music critic can be pretty a powerful influence actually.

Here in the Washington Post, we have Joe McLellan, who’s a very

sweet man. [Notice that this interview was held before the production

which he reviewed!] He’s a very bright man, and he writes

practically always very enthusiastically about new music. He’s

consistently that way. He’s not critical. On the other

hand, he’s enthusiastic, and he’s been very helpful in getting people to

come to things they might not come to otherwise. He probably sees

himself as a patron of a newer kind of music. BD: As you approach your 60th birthday,

what is perhaps the most surprising trend that you’ve seen in music

over that time?

BD: As you approach your 60th birthday,

what is perhaps the most surprising trend that you’ve seen in music

over that time?

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on September 5, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB two months later, and again in 1992 and 1997; and on WNUR in 2007 and 2013. A copy of the un-edited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern Univeristy. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.