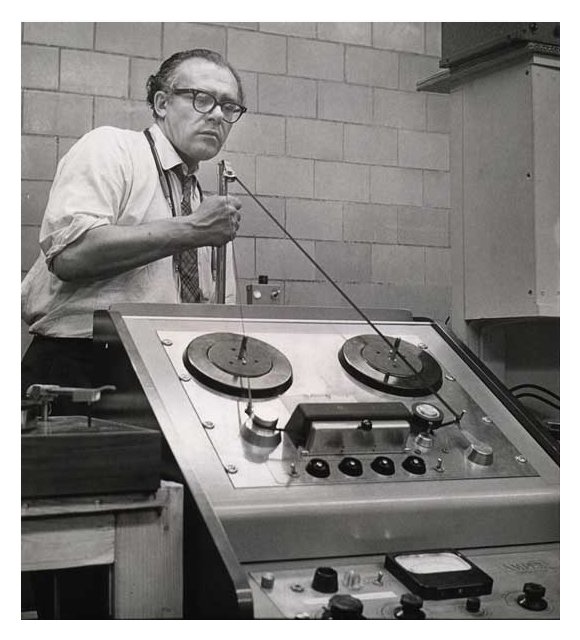

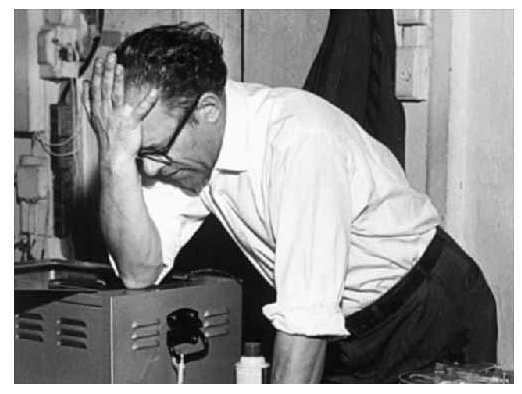

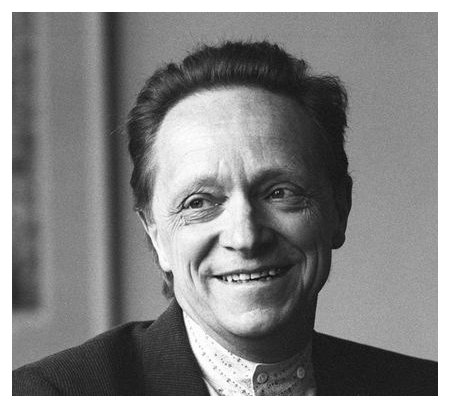

| Vladimir Ussachevsky (Hailar, China,

November 3, 1911 – New York, New York, January 2, 1990) was one of the pioneers

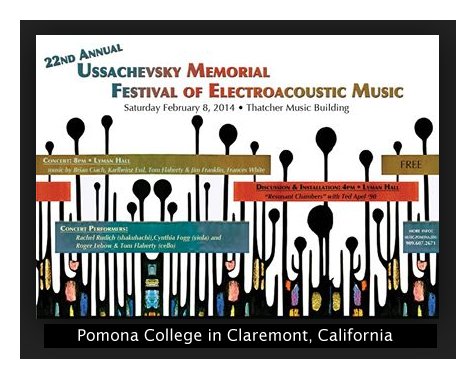

of 'tape music'. He was born in the Hailar District of China, in modern-day Inner Mongolia to an Imperial Russian Army officer assigned to protect Trans-Siberian Railway interests. He emigrated to the United States in 1930 and studied music at Pomona College in Claremont, California (B.A., 1935), as well as at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York (M.M., 1936, Ph.D., 1939).

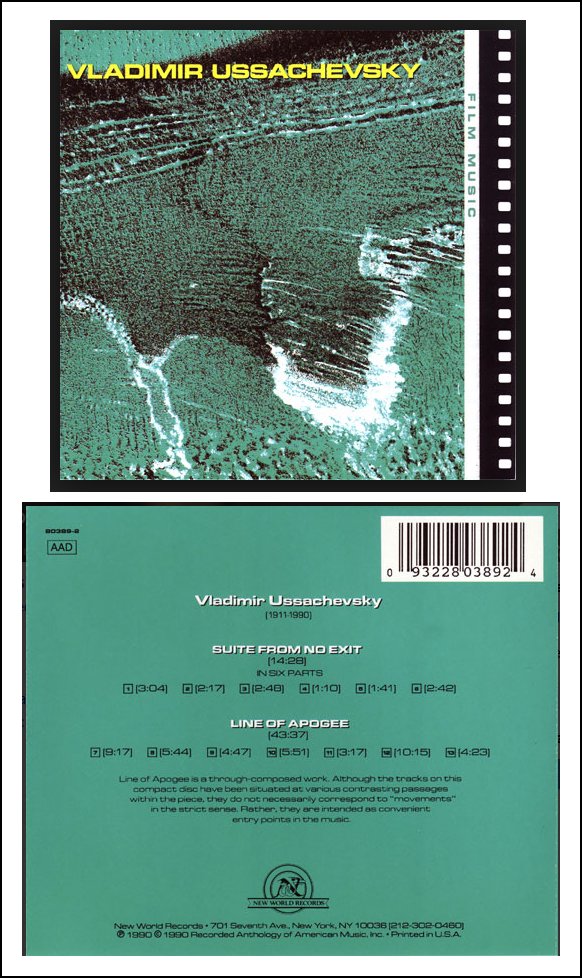

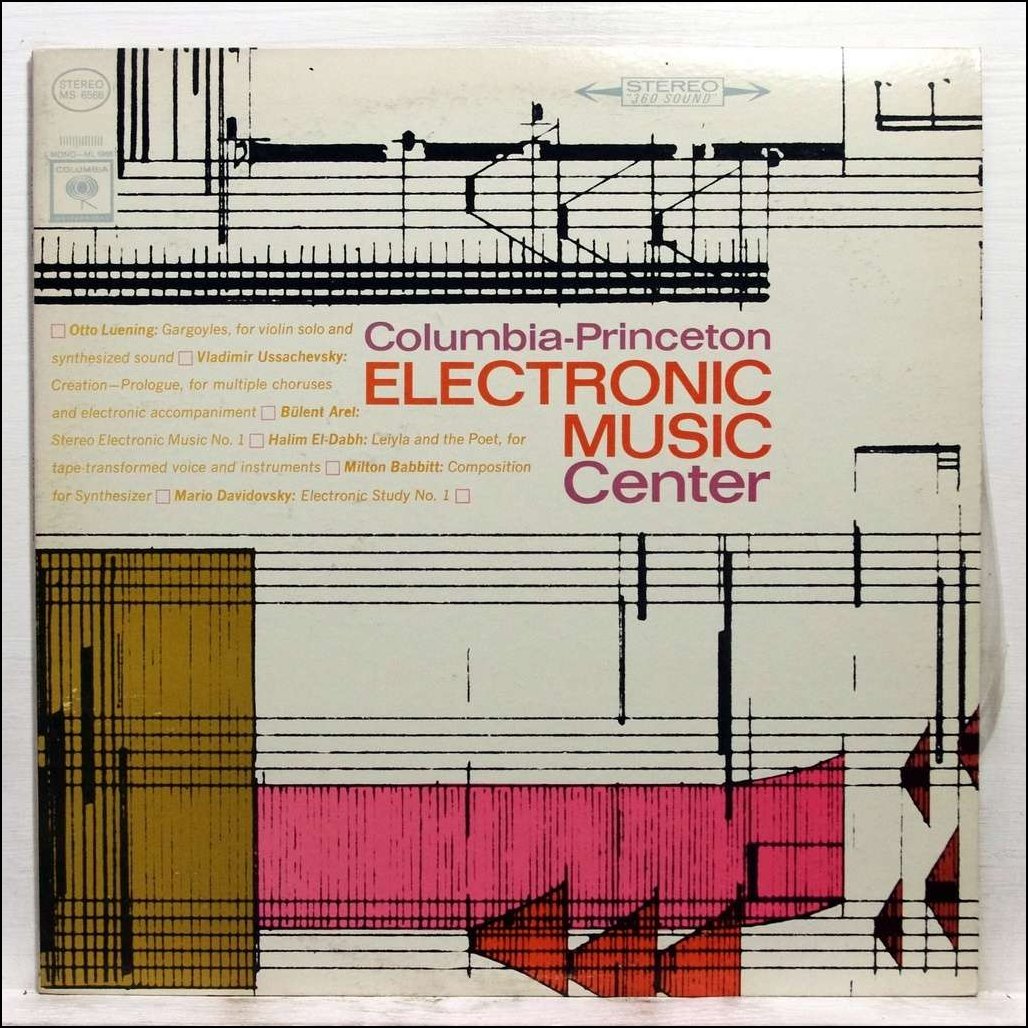

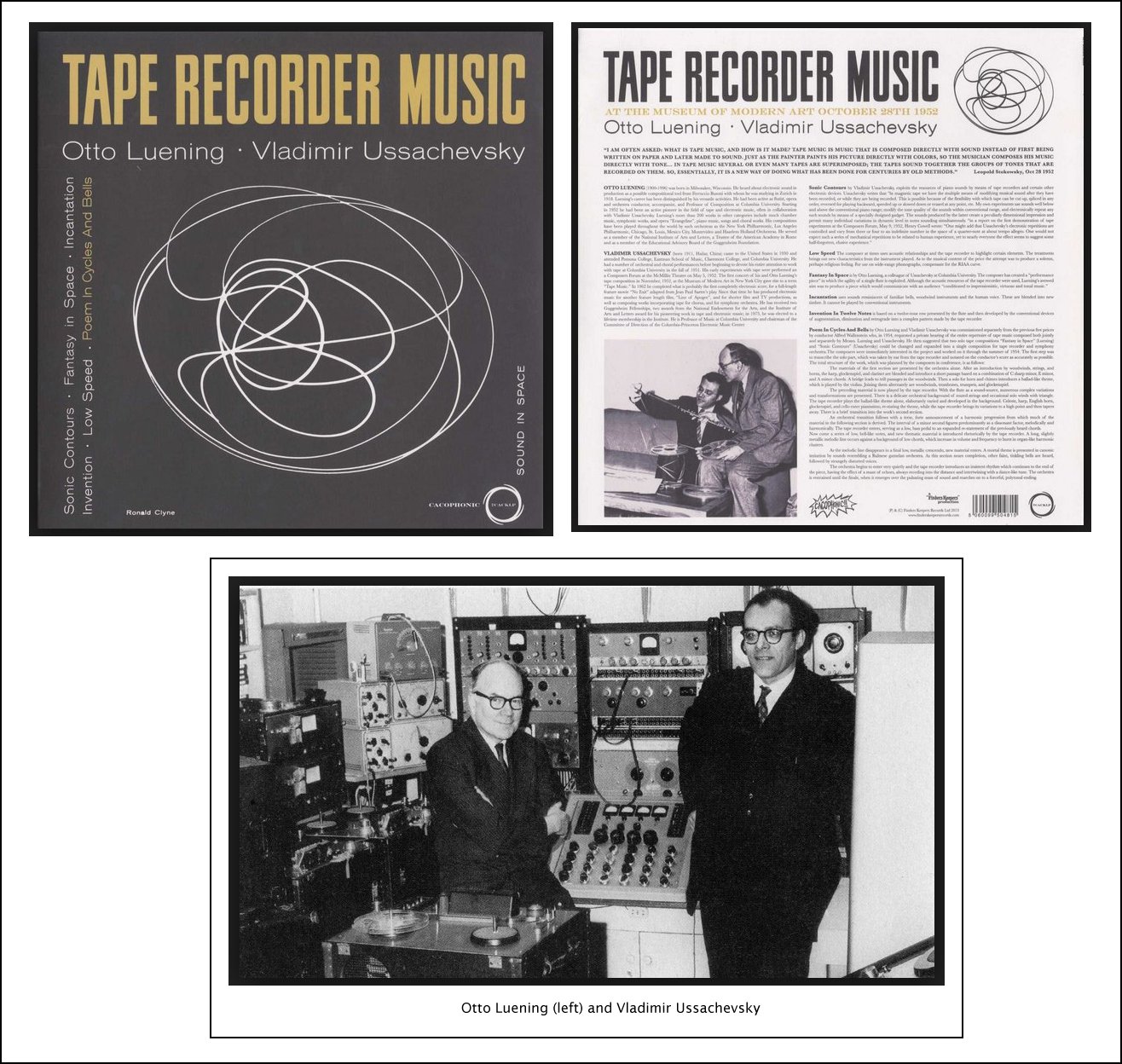

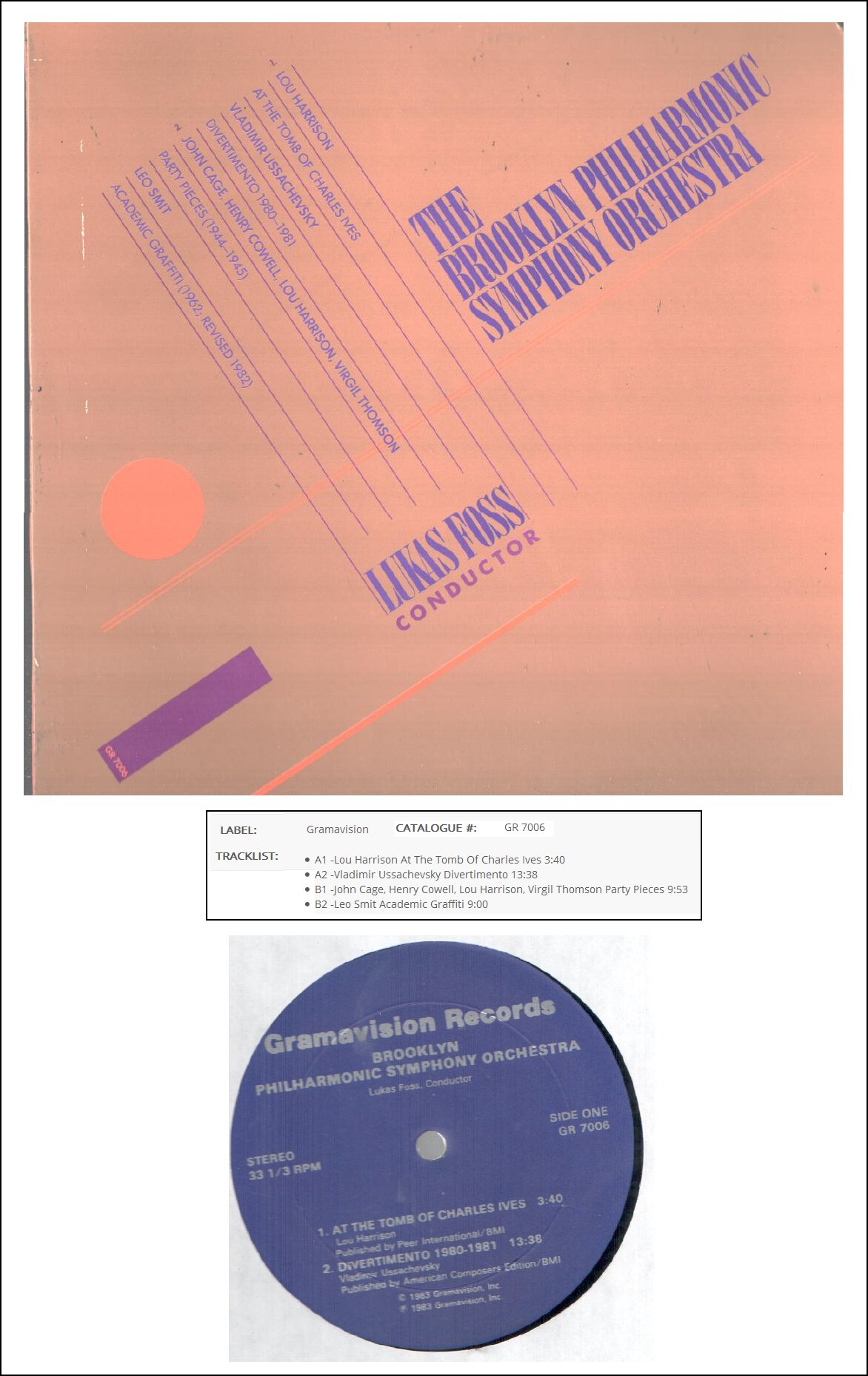

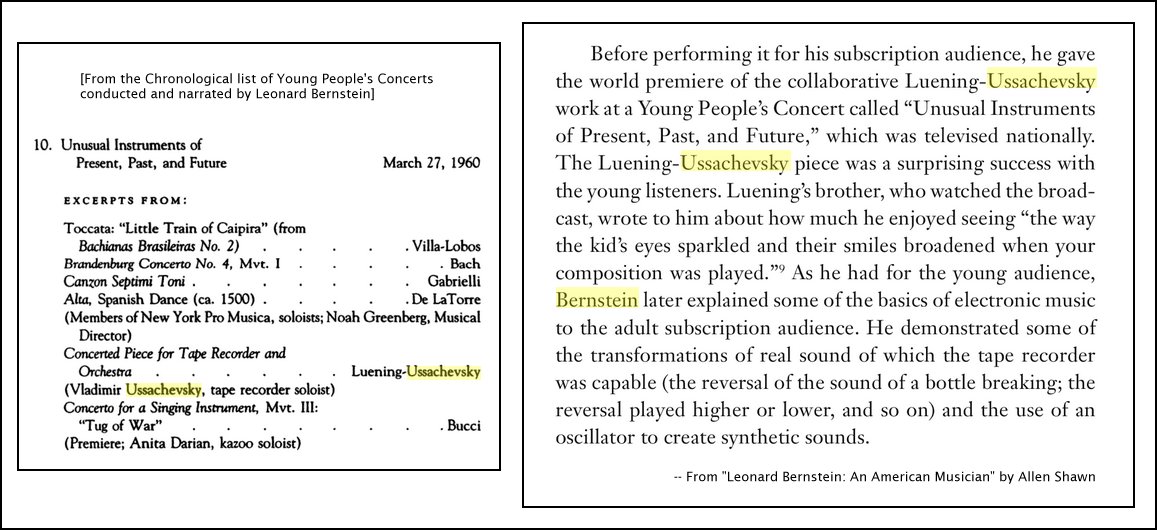

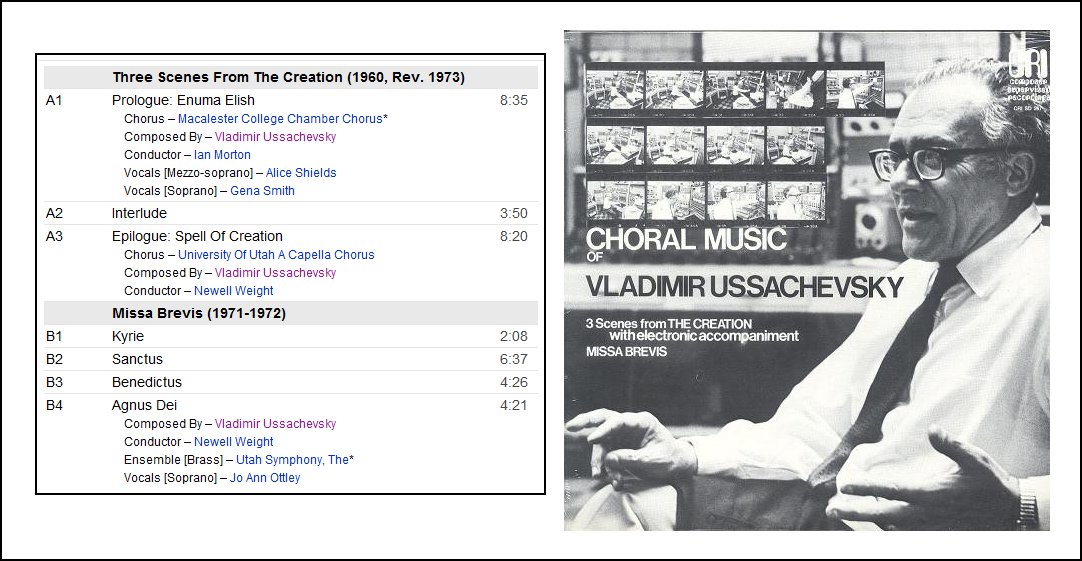

Ussachevsky's early, neo-Romantic works were composed for traditional instruments, but in 1951 he began composing electronic music. He served as president of the American Composers Alliance from 1968 to 1970 and was an advisory member of the CRI record label, which released recordings of a number of his compositions. Recordings of his music have also been released on the Capstone, d'Note, and New World labels. Some of the earlier LP items were later issued on CD. In 1947, following a stint with the U.S. Army Intelligence division in World War II, he joined the faculty of Columbia University, teaching there until his retirement in 1980. He also taught and was composer-in-residence at the University of Utah. He created the first electronic music in 1951 with his teacher Otto Luening. In October 1952, a live concert of electronic music by Luening and Ussachevsky at New York's Museum Of Modern Art was broadcast live and caused a sensation. It included Ussachevsky's Sonic Contours (1952), which electronically modifies the sound of a piano. Ussachevsky was one of the most significant pioneers in the composition of electronic music, and one of its most potent forces. He produced the first works of 'tape music,' a uniquely American synthesis of the French musique-concrète and the German pure electronic schools. He co-founded the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in 1959 and directed its course for the next twenty years. The Center was the leading electronic music studio in the United States. Two of his most powerful and innovative scores are Suite from No Exit (1962), from the film of Sartre’s play No Exit directed by Orson Welles, and the soundtrack for the avant-garde film, Line of Apogee (1967). Other legendary works that Ussachevsky composed were A Poem In Cycles And Bells (1954) for tape and orchestra (one of the earliest electro-acoustic pieces), which was based on Otto Luening's Fantasy In Space (1952) and his own Piece for Tape Recorder (1956) for tape. Later works included Creation Prologue (1961), Conflict (1971) and Creation Epilogue (1971), three parts of the multi-movement large-scale Creation, which were scored for choirs and electronics.

|

BD: Is there any correlation between this juxtaposition

of the younger generation and the older generation of composers, and perhaps

in the newspaper business, the old guys who worked with the manual typewriters

and now the new guys who know nothing but word processors?

BD: Is there any correlation between this juxtaposition

of the younger generation and the older generation of composers, and perhaps

in the newspaper business, the old guys who worked with the manual typewriters

and now the new guys who know nothing but word processors? BD:

That’s all right. I like the direction that our discussion is going.

BD:

That’s all right. I like the direction that our discussion is going. VU:

Everything that one does, to the best of his ability, should combine that

element of personal preference and personal novelty within the certain adventuresomeness

in structure, and especially nowadays, it should not be so far removed from

that mysterious comprehension level that it becomes rejected simply by virtue

of its complexity. We have gone through periods of extreme complexity,

and there are certain composers who are still sticking to it. I do not

approve myself of the simplicity and over-simplicity of minimalism, and I

blame it all on the generation of people who have been brought up hearing

the enormous repetitiousness of rock ‘n’ roll. Now, all the sudden,

there’s a serious music that seems to behave in the same templates or stem

out of the same patterns. I personally feel that it will go away somehow,

but at the same time, I don’t know whether we can accept again the extreme

complexity with very elaborate explanations of how this complexity has been

achieved as the next period. It’s hard to say what we should do next.

As you very well know, the percentage of the audience which is faithfully

willing to hear constantly new things is relatively small, even in any large

city, though I must say that in New York you do have a certain faithful

audience at every kind of contemporary music. Sometimes it’s more,

sometimes it’s less, and sometimes it’s somewhat embarrassingly less, but

it’s very seldom embarrassingly more. [Laughs]

VU:

Everything that one does, to the best of his ability, should combine that

element of personal preference and personal novelty within the certain adventuresomeness

in structure, and especially nowadays, it should not be so far removed from

that mysterious comprehension level that it becomes rejected simply by virtue

of its complexity. We have gone through periods of extreme complexity,

and there are certain composers who are still sticking to it. I do not

approve myself of the simplicity and over-simplicity of minimalism, and I

blame it all on the generation of people who have been brought up hearing

the enormous repetitiousness of rock ‘n’ roll. Now, all the sudden,

there’s a serious music that seems to behave in the same templates or stem

out of the same patterns. I personally feel that it will go away somehow,

but at the same time, I don’t know whether we can accept again the extreme

complexity with very elaborate explanations of how this complexity has been

achieved as the next period. It’s hard to say what we should do next.

As you very well know, the percentage of the audience which is faithfully

willing to hear constantly new things is relatively small, even in any large

city, though I must say that in New York you do have a certain faithful

audience at every kind of contemporary music. Sometimes it’s more,

sometimes it’s less, and sometimes it’s somewhat embarrassingly less, but

it’s very seldom embarrassingly more. [Laughs] BD:

Do you have this feeling within you?

BD:

Do you have this feeling within you?Scambi (Exchanges) is an electronic music

composition by the Belgian composer Henri Pousseur (1929-2009), realized in

1957 at the Studio di fonologia musicale di Radio Milano. In the summer of 1956, at the Darmstädter Ferienkurse, Pousseur met

Luciano Berio, who

invited him to come to Milan to work at the Studio di fonologia musicale of

Radio Milan. On his way to Milan on the train in the spring of 1957, Pousseur

formulated two goals for his new work. First, he wanted to design the work

in a way that permitted the listener to participate in its temporal formation,

which meant it would be composed of a number of small elements which could

be arranged in different ways. Second, it seemed necessary at that time to

use material that avoided the periodic character of traditional music, including

the internal structure of the sounds themselves. This meant starting from

white noise and filtering it to produce a range of noisy sounds with different

degrees of relative pitch. This came as an extension of the post-Webernian

goal of exploring structures opposed to traditional ones, especially in the

area of harmony, so that, in place of the concepts of polarity and causality

of traditional musical thinking, "Es soll alles schweben" (everything should

remain in suspension), as Webern put it.

In the summer of 1956, at the Darmstädter Ferienkurse, Pousseur met

Luciano Berio, who

invited him to come to Milan to work at the Studio di fonologia musicale of

Radio Milan. On his way to Milan on the train in the spring of 1957, Pousseur

formulated two goals for his new work. First, he wanted to design the work

in a way that permitted the listener to participate in its temporal formation,

which meant it would be composed of a number of small elements which could

be arranged in different ways. Second, it seemed necessary at that time to

use material that avoided the periodic character of traditional music, including

the internal structure of the sounds themselves. This meant starting from

white noise and filtering it to produce a range of noisy sounds with different

degrees of relative pitch. This came as an extension of the post-Webernian

goal of exploring structures opposed to traditional ones, especially in the

area of harmony, so that, in place of the concepts of polarity and causality

of traditional musical thinking, "Es soll alles schweben" (everything should

remain in suspension), as Webern put it.A third factor which preoccupied Pousseur was that the time available to carry out the work was relatively short. Consequently, it was necessary to find relatively quick methods for the generation and formation of the material. This was an important factor in deciding on techniques that deviated from the microstructural devices accepted almost exclusively in electronic composition until then. Scambi is unusual for an electronic work in having a mobile structure. It consists of sixteen pairs of segments (called "layers" by Pousseur) that may be assembled in many different ways. Pousseur's original idea was to supply these layers on separate reels of tape, so that the listener could assemble his own version. When first created, several different versions were realized, two by Berio, one by Marc Wilkinson, and two by the composer himself—a longer one of about six-and-a-half minutes and a shorter one lasting just over four minutes. One of Berio's versions is shorter still at 3:25. Pousseur established two principles for linking the segments together. The first is that there should be as complete a conformity in character as possible between the end of one segment and the beginning of the next, with the objective of accomplishing transitions as imperceptible as possible. The second is that the formal course should be marked by the successive dominance of the different characters. The process of assembly was complicated by the fact that the sequences were not all the same length, but it was not required that all thirty-two segments necessarily appear in all versions. Though Pousseur followed these rules himself, he regarded them only as suggestions, and Berio and Wilkinson did not conform to them when making their versions. Berio's structures, for example, are marked by an even distribution of the various characters, while Wilkinson's connections emphasize effects of contrast. |

VU:

Oh, I think so, but that’s been rather clear from the very first, so that

is the case. I always hid behind a very obvious idea — when

you play Furtwängler’s recording of Beethoven, that’s the same thing

because it’s Furtwängler’s recording, except that a composer has a perfect

right. In my particular case, that’s what I arrived at, and I don’t

want any other changes in it, and I don’t want any interpretations in it.

If anybody wants to interpret their own ideas, both Stockhausen and Cage have a number of things

in which you have opportunities for fiddling around any number of controls

— in both amplitude and timbre, plus the ring modulation

— in which no performance is ever the same. I’m just not

agreeing with that. Unquestionably, some performances will still be

more interesting than the others, in the same way in which some compositions

performed. For example, I have heard pieces in which there was a lot

of random give-and-take in the orchestra, where they play what they wish.

I heard of a performance in South America, where musicians were perhaps less

used to that sort of thing, where they played scales and pages. Then

so what? You’re suddenly listening to a boring orchestral tuning exercise.

[Both laugh]

VU:

Oh, I think so, but that’s been rather clear from the very first, so that

is the case. I always hid behind a very obvious idea — when

you play Furtwängler’s recording of Beethoven, that’s the same thing

because it’s Furtwängler’s recording, except that a composer has a perfect

right. In my particular case, that’s what I arrived at, and I don’t

want any other changes in it, and I don’t want any interpretations in it.

If anybody wants to interpret their own ideas, both Stockhausen and Cage have a number of things

in which you have opportunities for fiddling around any number of controls

— in both amplitude and timbre, plus the ring modulation

— in which no performance is ever the same. I’m just not

agreeing with that. Unquestionably, some performances will still be

more interesting than the others, in the same way in which some compositions

performed. For example, I have heard pieces in which there was a lot

of random give-and-take in the orchestra, where they play what they wish.

I heard of a performance in South America, where musicians were perhaps less

used to that sort of thing, where they played scales and pages. Then

so what? You’re suddenly listening to a boring orchestral tuning exercise.

[Both laugh][The material about the instrument

was copied from the Akai website in November, 2016.]

Akai Pro's EWI5000 is the latest addition to the EWI series, combining innovative instrument design, wireless connectivity, and a sound library by SONiVOX to create the most expressive and versatile wind instrument available to today's musicians. Building upon the legacy of the original Electronic Wind Instrument, Akai Professional created EWI5000 with the same objective in mind to deliver unprecedented musical expression to wind players everywhere. Experience the next generation in wind-performance technology with an instrument that's built for the contemporary player. With 2.4GHz low-latency wireless connectivity, EWI5000 empowers you to perform freely with a dynamic performance instrument in hand. It supports stereo wireless audio and includes a receiver for instant mobility on the stage or in the studio. EWI5000 also supports wired audio and MIDI connections for integrating with additional external performance and production hardware. Plus, its powered by a rechargeable lithium-ion battery, so you can take EWI5000 with you and play it anywhere. For precisely controlling volume and pitch dynamics, EWI5000 features an ultra-responsive mouth piece with an air-pressure level sensor and bite sensor. In addition, eight dedicated precision dials allow you to adjust instrument or effect parameters on the fly; tweak Filter, Reverb, Chorus, LFO, Breath Amount, Bite Amount, Semitone Tuning, and Fine Tuning for a sound that's as expressive as your playing. EWI5000 is a powerful instrument that expands the performance capabilities of woodwind and brass musicians alike. With support for multiple playing styles, its interface can be switched to flute, oboe, and saxophone fingering modes. An EVI (Electronic Valve Instrument) Mode is also included for brass players. Whether you're a classically trained flutist looking for a modern instrument, or a seasoned EWI player looking for finger-position flexibility, EWI5000 has you covered. USB-MIDI connectivity and a 5-pin MIDI output enable you to expand your sonic palette by controlling software synths, virtual samplers, or traditional MIDI modules. EWI5000 comes with a built-in 1/4-inch output for connecting it directly to PA systems and a 1/8-inch headphone output for practicing privately. A USB cable and wall adapter are included to recharge battery power via USB or wall power. EWI5000 comes loaded with more than 3GB of built-in high-quality sounds designed by SONiVOX, a leading creator of premium virtual instruments and software synthesis technologies. These instruments span across just about every music genre and put traditional orchestral sounds (e.g. horn, brass, and woodwind) and non-traditional sounds (e.g. progressive synths, basses, and leads) at your fingertips. Expand your creative capabilities with the EWI5000 Sound Editor software. This custom software editor is a powerful platform for manipulating EWI5000's sound library on your Mac or PC. Connect EWI5000 to your computer via USB; call up any instrument from the library; and use the filter, two LFOs, pan knob, tune control, and multiple envelopes to tweak it into something entirely new. Then, store your edits directly on your EWI5000 for a customised instrument library that's ready to perform whenever you are. Features Authentic wind-instrument performance and response with next-generation music technology Wireless stereo audio for onstage freedom (receiver included) 3GB of onboard, world-class acoustic and synth sounds created by SONiVOX Up to 6 hours of play time using the rechargeable lithium-ion battery (charging adapter included) 8 precision dials for quickly tweaking instrument and effect parameters USB port for USB-MIDI connection and battery recharging 1/4" audio output and 1/8" headphone output For more information, please visit the manufacturer's website.

|

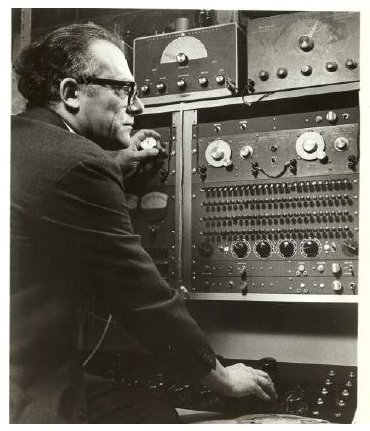

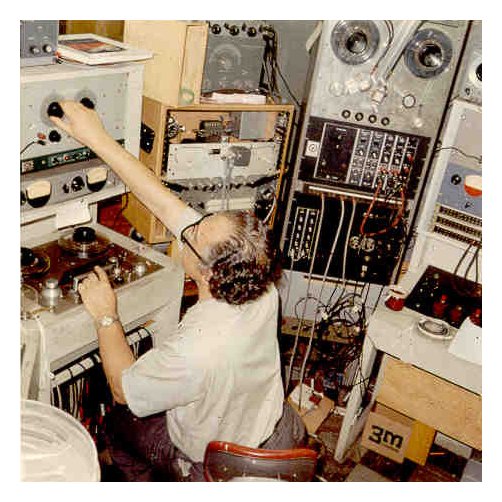

VU: Otto relinquished to me the technical production

of the electronic part. He mentioned in his book, The Odyssey of an American Composer,

that he preferred to concentrate on music. We would sit down and I

would try out things electronically, and then he would make certain choices.

But I had always been more technically inclined, and therefore we simply agreed

that this would be the case. However, I find that some people think

that Otto did all the music and I did all the technical, which is not so.

Each of the movements is done by an individual within the constraints of

the orchestration agreed upon, and with my being of help technically in putting

together the electronically generated, or electronically processed materials.

VU: Otto relinquished to me the technical production

of the electronic part. He mentioned in his book, The Odyssey of an American Composer,

that he preferred to concentrate on music. We would sit down and I

would try out things electronically, and then he would make certain choices.

But I had always been more technically inclined, and therefore we simply agreed

that this would be the case. However, I find that some people think

that Otto did all the music and I did all the technical, which is not so.

Each of the movements is done by an individual within the constraints of

the orchestration agreed upon, and with my being of help technically in putting

together the electronically generated, or electronically processed materials.

| Guggenheim Fellowships are grants that

have been awarded annually since 1925 by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial

Foundation to those "who have demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive

scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the arts". The roll of Fellows

includes numerous Nobel Laureates, Pulitzer and other prize winners. Each year, the foundation makes several hundred awards in each of two separate competitions. One is open to citizens and permanent residents of the United States and Canada, and the other to citizens and permanent residents of Latin America and the Caribbean. The performing arts are excluded, although composers, film directors, and choreographers are eligible. The fellowships are not open to students, only to "advanced professionals in mid-career" such as published authors. The fellows may spend the money as they see fit, as the purpose is to give fellows "blocks of time in which they can work with as much creative freedom as possible", but they should also be "substantially free of their regular duties". Applicants are required to submit references as well as a CV and portfolio. The Foundation receives between 3,500 and 4,000 applications every year. Approximately 220 Fellowships are awarded each year. The size of grant varies and will be adjusted to the needs of Fellows, considering their other resources and the purpose and scope of their plans. The average grant in the 2008 Canada and United States competition was approximately US $43,200.

The Prix de Rome was a French scholarship for arts students, initially for painters and sculptors, that was established in 1663 during the reign of Louis XIV. Winners were awarded a bursary that allowed them to stay in Rome for three to five years at the expense of the state. The prize was extended to architecture in 1720, music in 1803, and engraving in 1804. The prestigious award was abolished in 1968 by André Malraux, the Minister of Culture. |

BD: So we’re back to the comment you made earlier,

that perhaps high school or even junior high school students are more open

ideas.

BD: So we’re back to the comment you made earlier,

that perhaps high school or even junior high school students are more open

ideas.© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on October 31, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1990, and again in 1991 and 1996. This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.