Frank Guarrera, 83, Lyric Baritone at the Met,

Is Dead

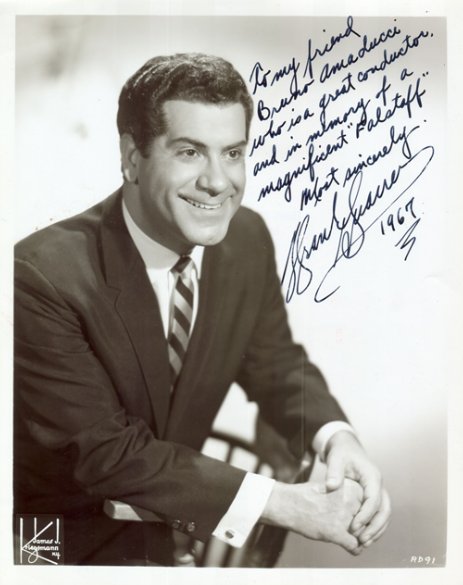

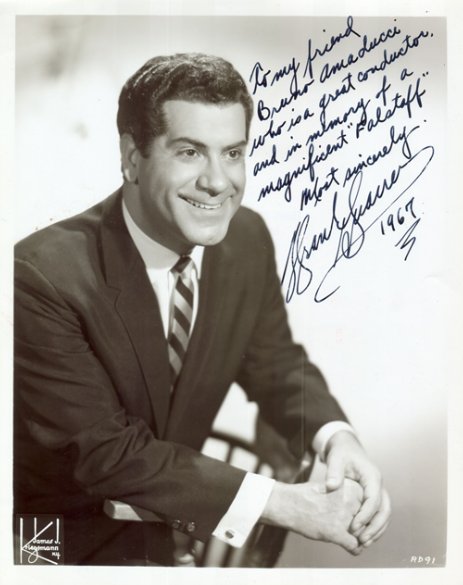

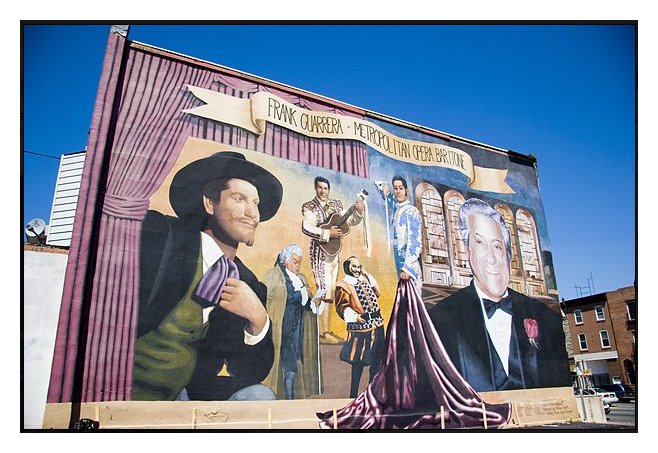

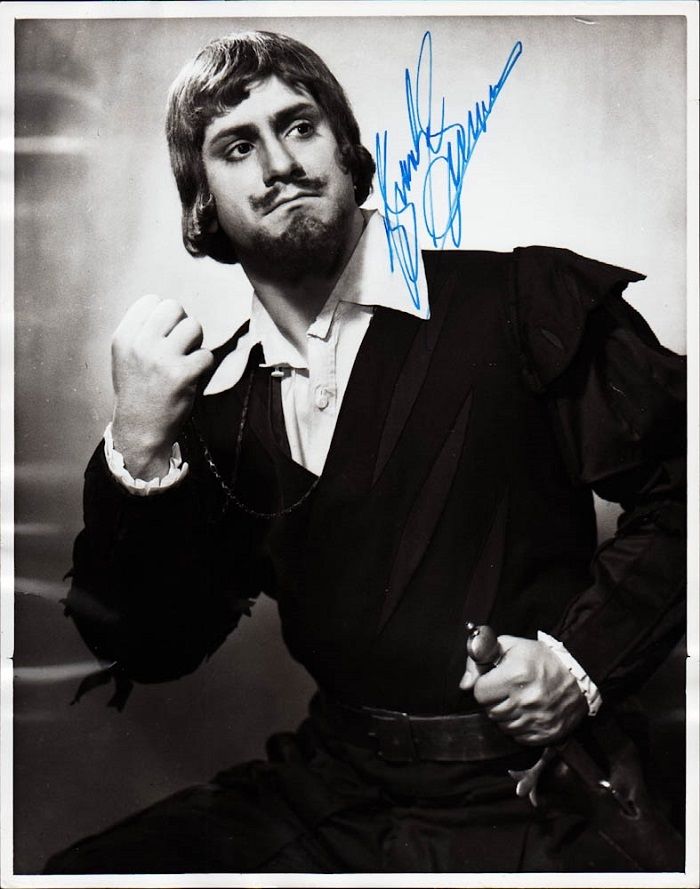

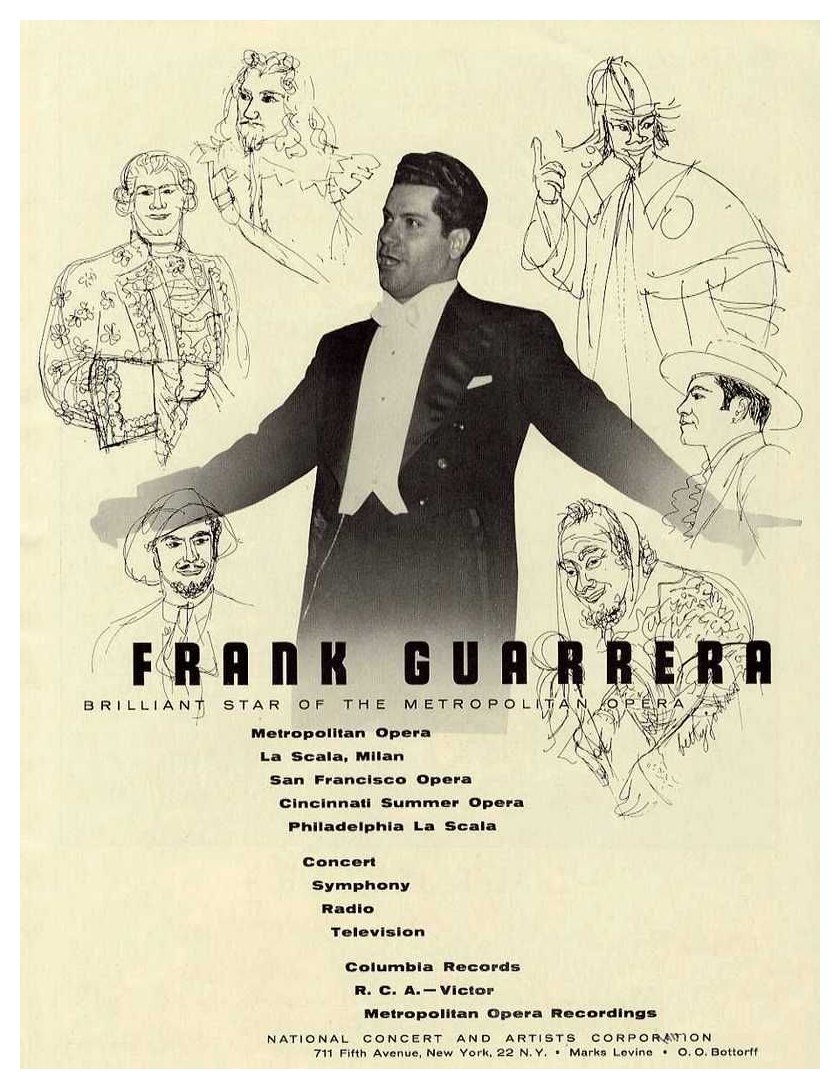

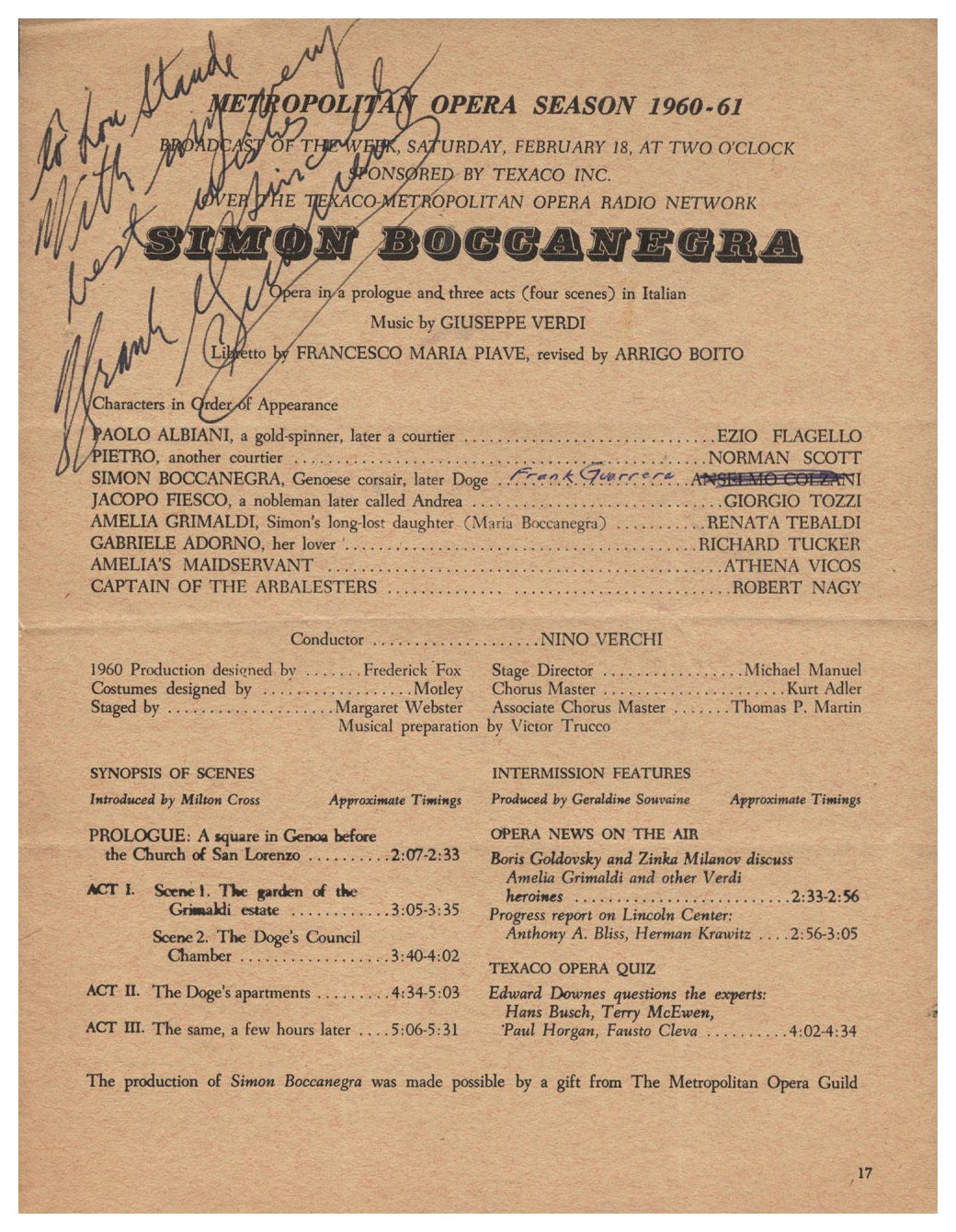

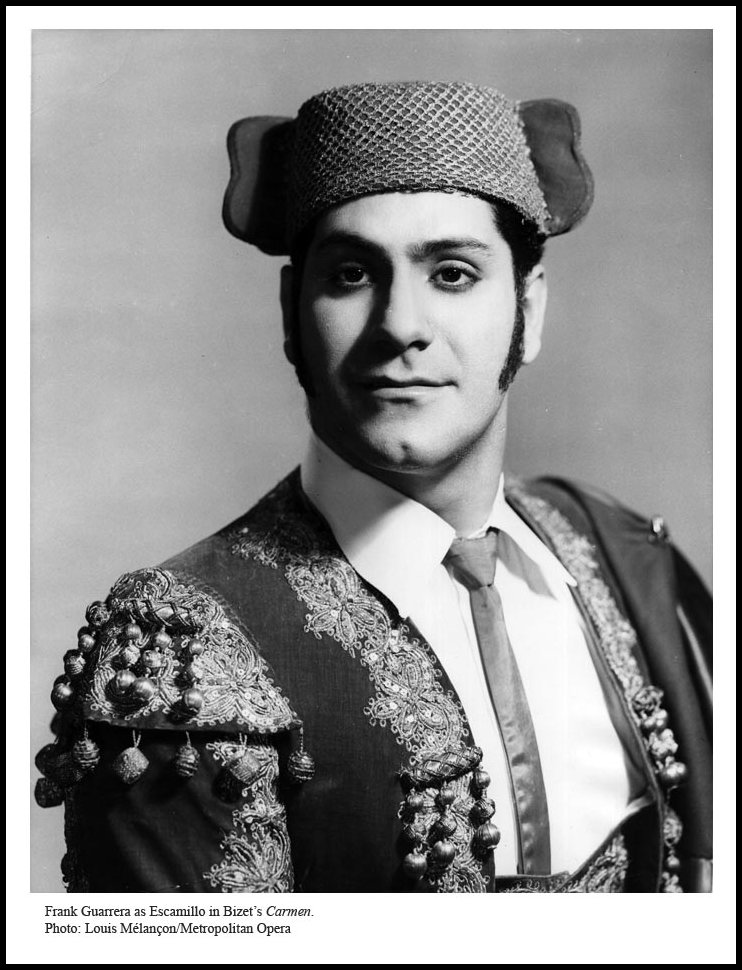

By ANNE MIDGETTE Published: The New York Times, November 27, 2007 [Text only; photo added for this website presentation] Frank Guarrera, a lyric baritone who sang at the Metropolitan Opera for nearly 30 years, died on Friday at his home in Bellmawr, N.J. He was 83. The cause was complications from diabetes, said his daughter, Valerie Bisquert. With his slender but firm voice and winning stage presence, Mr. Guarrera was a fixture at the Met in a number of roles: Escamillo in “Carmen” (his debut role in 1948), Marcello in “La Bohème,” Valentin in “Faust.” He also essayed larger, Verdian roles with honor, if not quite the vocal opulence of contemporaries like Robert Merrill, or Leonard Warren, whom he replaced as “Simon Boccanegra” a few days after Mr. Warren’s death onstage in 1960. He made the most of the role, but Rudolf Bing ultimately replaced him, saying, “You’re not big enough.” He was, however, big enough for Arturo Toscanini. In 1948, when the 24-year-old Mr. Guarrera was participating in the Metropolitan Opera’s “Auditions of the Air” (a precursor of the current National Council Auditions), which he eventually won, Toscanini heard him on the radio singing Ford’s monologue from “Falstaff” and arranged for an audition. The result was Mr. Guarrera’s engagement at La Scala in Boito’s “Nerone” on the 30th anniversary of Boito’s death. It was the first of several performances under Toscanini; Mr. Guarrera sang Ford on the conductor’s legendary 1950 “Falstaff” broadcasts, still available on CD. “Even now, I get an occasional royalty check,” Mr. Guarrera told the critic Martin Bernheimer in 2003 for the magazine Opera News. Frank Guarrera was born in Philadelphia on Dec. 3, 1923. After discovering his voice at the age of 15 in the high school glee club, he won entrance to the Curtis Institute of Music, but his studies were interrupted by service in the Navy during the war; a sympathetic officer, hearing his musical talent, assigned him to band duty, meaning that he had to rapidly learn to play an instrument. After the war, he finished his studies at Curtis before winning his Met contract. His final role at the Met was Gianni Schicchi, which he last sang in 1976. After his retirement from the stage, he taught at the University of Washington in Seattle for 10 years, a stint that ended when his wife, Adelina, suffered a stroke and he brought her back to the East to care for her; she died in 2000. In addition to his daughter, of Washingtonville, N.Y., he is survived by a son, Dennis Guarrera, of Glendale, Ariz., and two granddaughters. His career is lavishly commemorated in Philadelphia, where, at the corner of Broad and Tasker Streets, there is a multistory mural depicting him in some of his greatest roles [shown below].

|

BD: When you

were singing in different auditoriums, did you use the same vocal technique?

BD: When you

were singing in different auditoriums, did you use the same vocal technique?

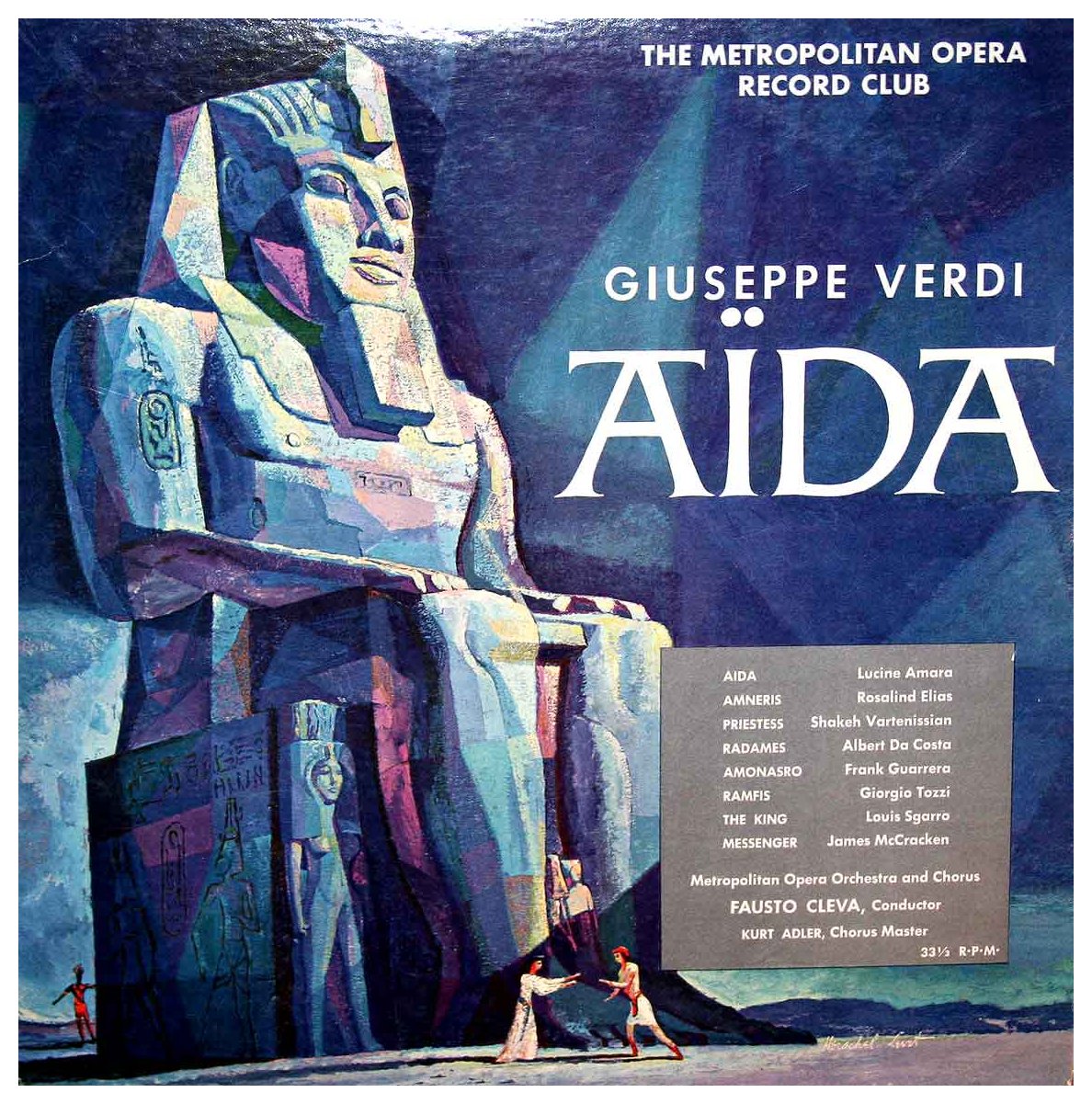

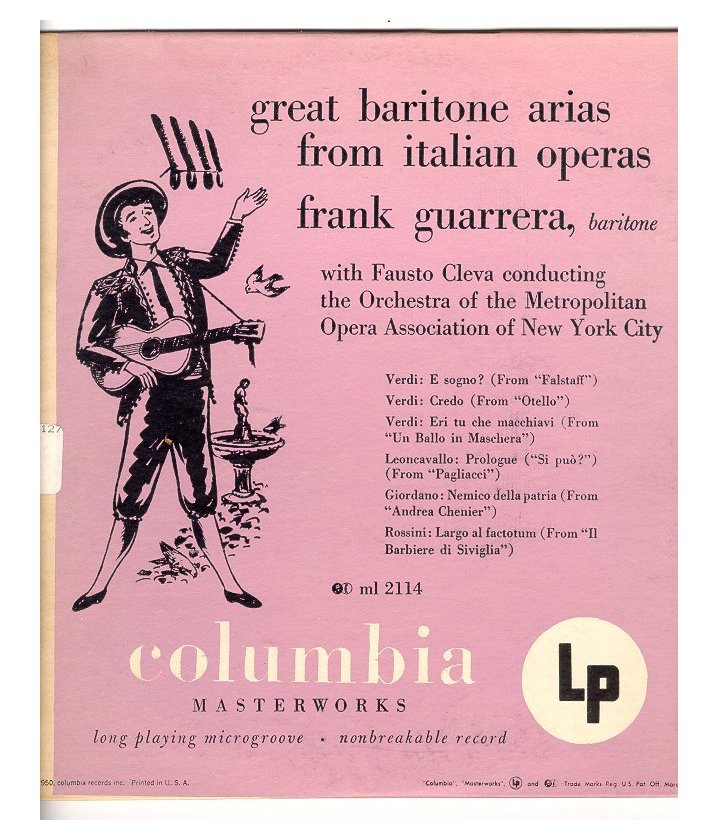

Frank Guarrera appeared in several

recordings of the Metropolitan Opera Record Club, a division (or branch -

both terms are used on various jackets) of Book-of-the-Month Club, Inc.

According to a published source, there were nineteen operas, each “abridged

for home listening”, or simply selections on one or two LPs. All were

recorded between November of 1955 and February of 1957 in New York City.

Besides Amonasro in Aïda (shown

below), Guarrera sang Dr. Malatesta in Don Pasquale (with Baccaloni, Wilson,

Anthony; Kozma) and Tonio in Pagliacci

(with Amara, Da Costa, Marsh, Anthony; Cleva) which were both single discs,

and two-disc sets as Count Di Luna in Il

Trovatore (with Curtis-Verna, Baum, Elias; Rudolf), Baron Scarpia in

Tosca (with Kirsten, Barioni, Harvuot,

Baccaloni, De Paolis, Cehanovsky; Mitropoulos), and the title character in

Eugene Onegin (in English

with Amara, Elias, Tucker, Tozzi, Lipton, Cehanovsky; Mitropoulos).

Notice that James McCracken sings the comprimario role of the Messenger! He also sings Ruiz and a Messenger in Il Trovatore. |

BD: So you make

use of all the recordings that have been made?

BD: So you make

use of all the recordings that have been made? FG: Oh, he’s

a big show-off! He is all of the things that personify the ‘torero’, the bull-fighter in the Spanish

bull ring. It’s paradoxical because it’s a French opera set in Spain,

so you are singing in French and you have to try and act Spanish. I

play him as a bragger because he does brag in his aria. He tells everybody

how great he is! If you read the text, that’s exactly what he is saying.

He says that here comes the Toreador, and he kills the bull with dispatch,

and at the end of it everyone applauds. At that point in the opera

he sees Carmen, and he sashays over and says, “What’s

your name, kiddo?” She tells him her name and

he says, “Okay, I’m going to dedicate my next bull to

you when I fight next Sunday! Won’t you come and enjoy the bullfight?”

She walks off, and little does he know that Carmen really is going

to use him. She’s a much more complex and much more interesting person

than Escamillo. He’s really a caricature of the bullfighter, but Carmen

pits one man against another. She’s really a fabulous character in

the opera. Of course, José has his hang-ups too. He’s torn

between the love of this woman and his duty. He’s never seen anything

like this in his life, and his Spanish blood is boiling. His passion

comes up, and he’s got this poor little girlfriend, Micaëla, who he

tosses aside for this Carmen. He gives up his reputation because he

deserts the army and joins her band. So Carmen had a tremendous influence

with all of the men around her. Even with Escamillo! She manages

to lure him into her clutches, although Escamillo wasn’t as unfortunate as

José. It’s fate!

FG: Oh, he’s

a big show-off! He is all of the things that personify the ‘torero’, the bull-fighter in the Spanish

bull ring. It’s paradoxical because it’s a French opera set in Spain,

so you are singing in French and you have to try and act Spanish. I

play him as a bragger because he does brag in his aria. He tells everybody

how great he is! If you read the text, that’s exactly what he is saying.

He says that here comes the Toreador, and he kills the bull with dispatch,

and at the end of it everyone applauds. At that point in the opera

he sees Carmen, and he sashays over and says, “What’s

your name, kiddo?” She tells him her name and

he says, “Okay, I’m going to dedicate my next bull to

you when I fight next Sunday! Won’t you come and enjoy the bullfight?”

She walks off, and little does he know that Carmen really is going

to use him. She’s a much more complex and much more interesting person

than Escamillo. He’s really a caricature of the bullfighter, but Carmen

pits one man against another. She’s really a fabulous character in

the opera. Of course, José has his hang-ups too. He’s torn

between the love of this woman and his duty. He’s never seen anything

like this in his life, and his Spanish blood is boiling. His passion

comes up, and he’s got this poor little girlfriend, Micaëla, who he

tosses aside for this Carmen. He gives up his reputation because he

deserts the army and joins her band. So Carmen had a tremendous influence

with all of the men around her. Even with Escamillo! She manages

to lure him into her clutches, although Escamillo wasn’t as unfortunate as

José. It’s fate!© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Seattle, Washington, on August 7, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1993 and 1998. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.