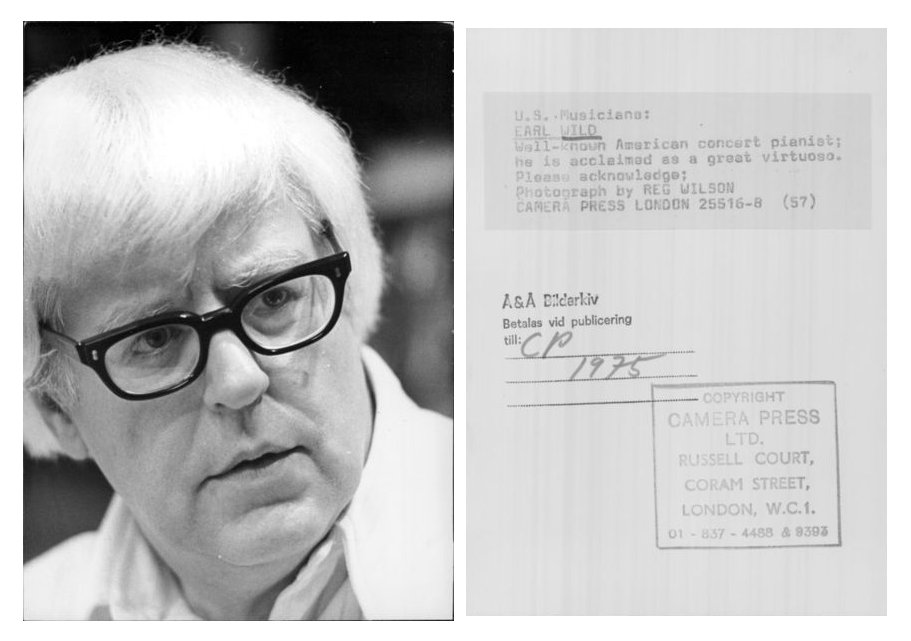

| Royland Earl Wild was born in Pittsburgh,

Pennsylvania, in 1915. He was a musically precocious child and studied under

Selmar Janson at Carnegie-Tech University, and later with Marguerite Long,

Egon Petri, and Helene Barere (the wife of Simon Barere), among others.

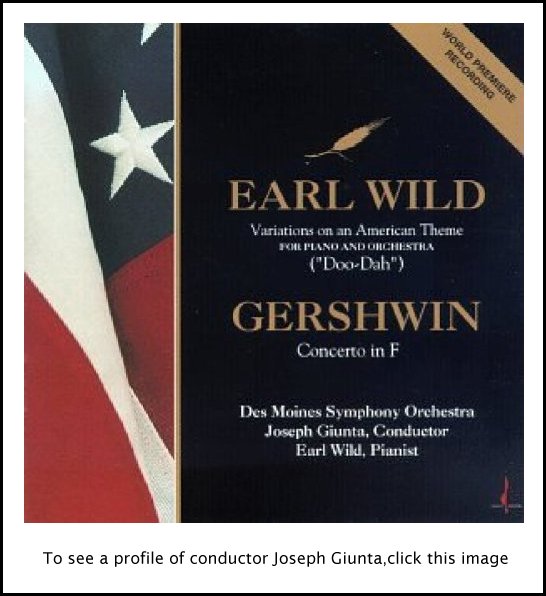

As a teenager, he started making transcriptions of romantic music and composition. In 1931 he was invited to play at the White House by President Herbert Hoover. The next five presidents (Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson), also invited him to play for them, and Wild remains the only pianist to have played for six consecutive presidents. In 1937, Wild was hired as a staff pianist for the NBC Symphony Orchestra, and in 1939 he became the first pianist to perform a recital on U.S. television. Wild later recalled that the small studio became so hot under the bright lights that the ivory piano keys started to warp. In 1942, Arturo Toscanini invited him for a performance of Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue, which was, for Wild, a resounding success, although Toscanini himself has been criticized for not understanding the jazz idiom in which Gershwin wrote. During World War II, Wild served in the United States Navy playing 4th flute in the Navy band. He often traveled with Eleanor Roosevelt while she toured the United States supporting the war effort. Wild's duty was to perform the national anthem on the piano before she spoke. A few years after the war he moved to the newly formed American Broadcasting Company (ABC) as a staff pianist, conductor and composer until 1968. Wild created numerous virtuoso solo piano transcriptions including 14 songs by Rachmaninoff, and works on themes by Gershwin. His Grand Fantasy on Airs from Porgy and Bess was the first extended piano paraphrase on an American opera. He also wrote a number of original works including a large-scale Easter oratorio, Revelations (1962), the choral work The Turquoise Horse (1976), and the Doo-Dah Variations on a theme by Stephen Foster (1992) for piano and orchestra. His Sonata 2000 had its first performance in 2003 and was recorded by Wild for Ivory Classics. Wild recorded for several labels. Under his teacher, Selmar Janson, Wild had learned Xaver Scharwenka's Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor, which Janson had studied directly with the composer, his own teacher. When, over 40 years later, Erich Leinsdorf asked Wild to record the concerto, he was able to say "I've been waiting by the phone for forty years for someone to ask me to play this".

In 1997 he was the first pianist to stream a performance over the Internet. Wild, who was openly gay, lived in Columbus, Ohio and Palm Springs, California with his domestic partner of 38 years, Michael Rolland Davis. He died aged 94 of congestive heart disease at home in Palm Springs. |

Bruce Duffie: ...you are literally in the spotlight!

Bruce Duffie: ...you are literally in the spotlight! BD: Does the audience come with preconceived ideas,

or do they come with more open minds?

BD: Does the audience come with preconceived ideas,

or do they come with more open minds? BD: With the vast amount of repertoire to be played,

how do you decide which works you will learn and will live with for a while?

BD: With the vast amount of repertoire to be played,

how do you decide which works you will learn and will live with for a while? EW: Oh yes, very much. I was listening

to music the other day, and I thought that all of a sudden better music

is going to have something that is special because it demands attention

and it’s not egotistical. The listener doesn’t have to get up and show

off, and do their thing like wiggle their bodies! Better music has

something to attract people, and all of a sudden most of the very cheap music

will have the same effect as a bad restaurant where the food is cheap.

It has to have more texture and something that you can live with for a while.

To me there’s nothing sadder than seeing an aging rock star. No matter

how much money they’ve made, when you see this it’s very sad, and they live

in a whole phony world.

EW: Oh yes, very much. I was listening

to music the other day, and I thought that all of a sudden better music

is going to have something that is special because it demands attention

and it’s not egotistical. The listener doesn’t have to get up and show

off, and do their thing like wiggle their bodies! Better music has

something to attract people, and all of a sudden most of the very cheap music

will have the same effect as a bad restaurant where the food is cheap.

It has to have more texture and something that you can live with for a while.

To me there’s nothing sadder than seeing an aging rock star. No matter

how much money they’ve made, when you see this it’s very sad, and they live

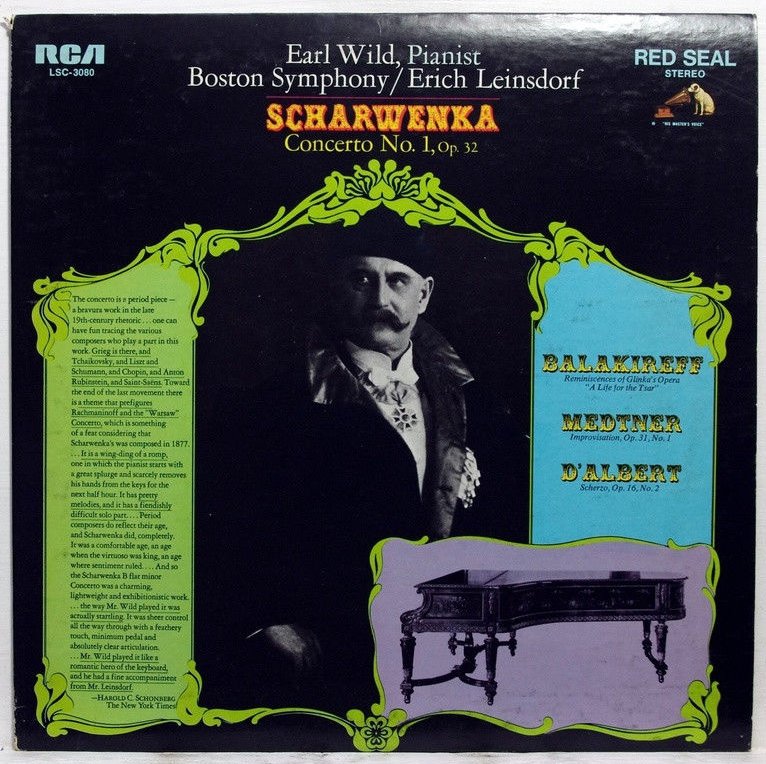

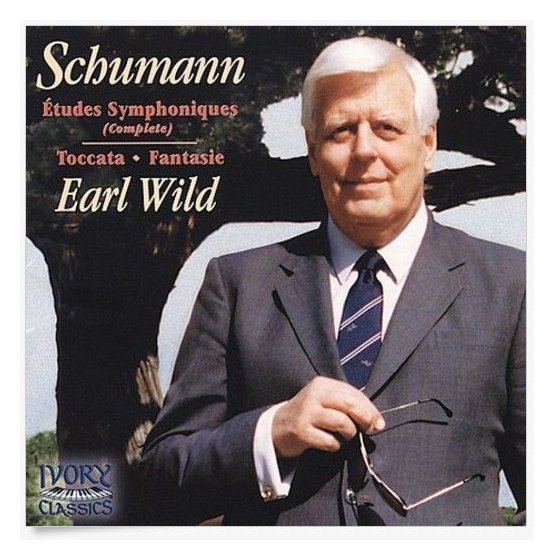

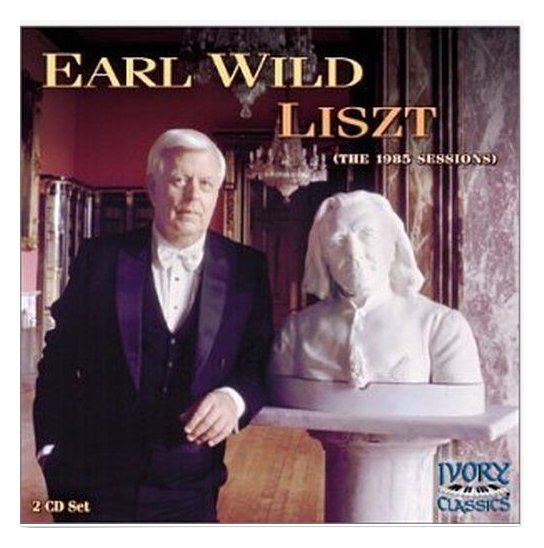

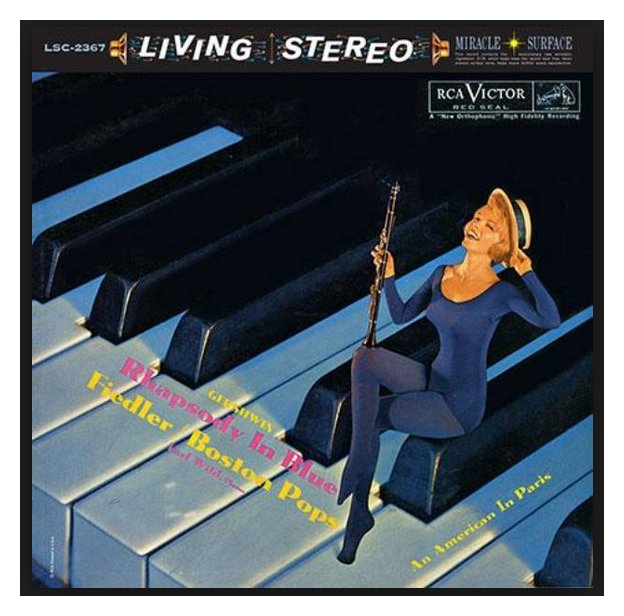

in a whole phony world. EW: If you make records you have to have some

kind of promotion. They sell the records. But still, it’s funny.

My first record with RCA was in 1959 with Arthur Fiedler. I did the

Rhapsody in Blue and American in Paris, and I never thought

that it would last. [Photo of original

record jackets is shown at right.] It’s still selling, and

now it’s on CD. It made more money for the Boston Pops Orchestra than

any other record that they ever put out, and it still sounds good, but I

wasn’t aware of it then. All during the 60s I made records that are

still out.

EW: If you make records you have to have some

kind of promotion. They sell the records. But still, it’s funny.

My first record with RCA was in 1959 with Arthur Fiedler. I did the

Rhapsody in Blue and American in Paris, and I never thought

that it would last. [Photo of original

record jackets is shown at right.] It’s still selling, and

now it’s on CD. It made more money for the Boston Pops Orchestra than

any other record that they ever put out, and it still sounds good, but I

wasn’t aware of it then. All during the 60s I made records that are

still out. BD: He was playing music?

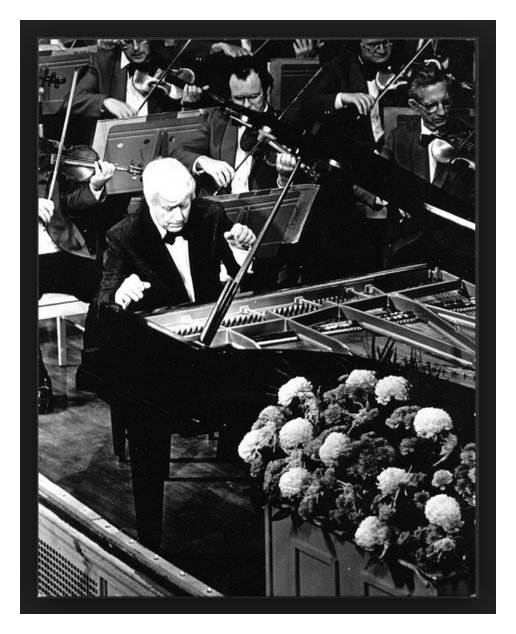

BD: He was playing music? EW: It’s your opinion the first time playing a

composition, and if anyone plays it afterwards they always look to that as

a guide. It’s always interesting. As you know I was with Toscanini

in the NBC Symphony for eight years in the keyboard department, and when he

played the Shostakovich Seventh Symphony

for the first time I played in this piece. After he finished, he put

the baton down on the stand and said, “After me come

the interpreters!” It was very interesting because

he had memorized that piece in two weeks. It’s an hour and some minutes

long, and he even corrected parts during the rehearsals. So it was

a great display of his genius. He was probably the most unusual of

all the conductors that I’ve ever worked with, and the greatest genius.

He lived a little too long because he outlived his period of music.

Stravinsky had come along and Toscanini couldn’t do very much with things

like Petrushka. It was foreign

to him. He did it, but it was foreign to him and he was not comfortable.

But the things in which he had worked with the composers, like Puccini and

all these people one after the other... He showed me a handkerchief

that Wagner had given him. It was a big handkerchief, a large one

that looked like a lady’s scarf, and was all covered with embroidery daisies.

It was very beautiful. It was loud but beautiful! He must have

been maybe fifteen or sixteen at the time, and it’s always a shock to hear

that from someone. When I was in my early teens, I knew people who

had played with Brahms. Egon Petri told me once that he talked to a

man who had heard Beethoven, and the review wasn’t good! [Both laugh]

EW: It’s your opinion the first time playing a

composition, and if anyone plays it afterwards they always look to that as

a guide. It’s always interesting. As you know I was with Toscanini

in the NBC Symphony for eight years in the keyboard department, and when he

played the Shostakovich Seventh Symphony

for the first time I played in this piece. After he finished, he put

the baton down on the stand and said, “After me come

the interpreters!” It was very interesting because

he had memorized that piece in two weeks. It’s an hour and some minutes

long, and he even corrected parts during the rehearsals. So it was

a great display of his genius. He was probably the most unusual of

all the conductors that I’ve ever worked with, and the greatest genius.

He lived a little too long because he outlived his period of music.

Stravinsky had come along and Toscanini couldn’t do very much with things

like Petrushka. It was foreign

to him. He did it, but it was foreign to him and he was not comfortable.

But the things in which he had worked with the composers, like Puccini and

all these people one after the other... He showed me a handkerchief

that Wagner had given him. It was a big handkerchief, a large one

that looked like a lady’s scarf, and was all covered with embroidery daisies.

It was very beautiful. It was loud but beautiful! He must have

been maybe fifteen or sixteen at the time, and it’s always a shock to hear

that from someone. When I was in my early teens, I knew people who

had played with Brahms. Egon Petri told me once that he talked to a

man who had heard Beethoven, and the review wasn’t good! [Both laugh] BD: [With a gentle nudge] You don’t want

to hear an A major chord for twenty minutes?

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You don’t want

to hear an A major chord for twenty minutes?

EW: [Interrupting] Oh, I’m not sure.

The pianos had to be in better shape. Naturally his piano didn’t project

like the ones that came immediately afterwards, or that Liszt had made,

but at least they were plausible for their time. These things that

they pull out and play for us now make me laugh! It’s very funny.

In London I went to this famous collector’s home, and I played on every type

of instrument that was made since Bach’s day. The one that I liked

the most was the Clementi piano that had an echo effect on it. It was

beautiful. It was small but beautiful. The fortepianos didn’t

seem to sound as well, and their sound wasn’t elegant at all. I understand

that at Harvard they are going to restore Wagner’s piano. That’s all

very nice and it’s historical and it’s wonderful, but it’s a fragile business

and it’s only imagination. So I prefer to deal only modern instruments.

EW: [Interrupting] Oh, I’m not sure.

The pianos had to be in better shape. Naturally his piano didn’t project

like the ones that came immediately afterwards, or that Liszt had made,

but at least they were plausible for their time. These things that

they pull out and play for us now make me laugh! It’s very funny.

In London I went to this famous collector’s home, and I played on every type

of instrument that was made since Bach’s day. The one that I liked

the most was the Clementi piano that had an echo effect on it. It was

beautiful. It was small but beautiful. The fortepianos didn’t

seem to sound as well, and their sound wasn’t elegant at all. I understand

that at Harvard they are going to restore Wagner’s piano. That’s all

very nice and it’s historical and it’s wonderful, but it’s a fragile business

and it’s only imagination. So I prefer to deal only modern instruments. EW: Yes. I have to tell you about him.

Toscanini liked the Third Symphony

of Roy Harris, which is his best piece, I think. And at one time,

Frank Black [shown in photo at left]

was conducting the Fifth Symphony

of Roy Harris with the NBC Symphony, and I went to the rehearsal.

I was the only one there in the audience. They allowed me to come

in because they knew my face! So all of a sudden, Toscanini appeared

and he came over to see who was sitting there. When he got close enough,

he recognized me and sat down beside me. All during the rehearsal

he kept muttering, and when it was over he looked at me and said, “It’s

full of shit!” [Both roar laughing] He

hated the Fifth, but the Third is good. There’s lots of

interesting things from that period that need to be sought out and put out

front again, because we might as well play that as all the other music we

play.

EW: Yes. I have to tell you about him.

Toscanini liked the Third Symphony

of Roy Harris, which is his best piece, I think. And at one time,

Frank Black [shown in photo at left]

was conducting the Fifth Symphony

of Roy Harris with the NBC Symphony, and I went to the rehearsal.

I was the only one there in the audience. They allowed me to come

in because they knew my face! So all of a sudden, Toscanini appeared

and he came over to see who was sitting there. When he got close enough,

he recognized me and sat down beside me. All during the rehearsal

he kept muttering, and when it was over he looked at me and said, “It’s

full of shit!” [Both roar laughing] He

hated the Fifth, but the Third is good. There’s lots of

interesting things from that period that need to be sought out and put out

front again, because we might as well play that as all the other music we

play.

© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 9, 1989. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following day, and again in 1990, 1995, and 2000. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.