A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

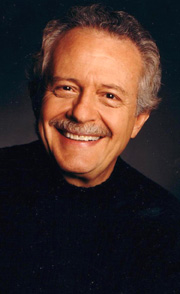

| The American conductor Jorge

Mester was born in Mexico City in 1935 to parents who had emigrated from Hungary.

He studied conducting with Jean Morel at The Juilliard School in New York,

also working with Leonard Bernstein at the Berkshire Music Center, and with

Albert Wolff. In 1955 he made his debut conducting the National Symphony

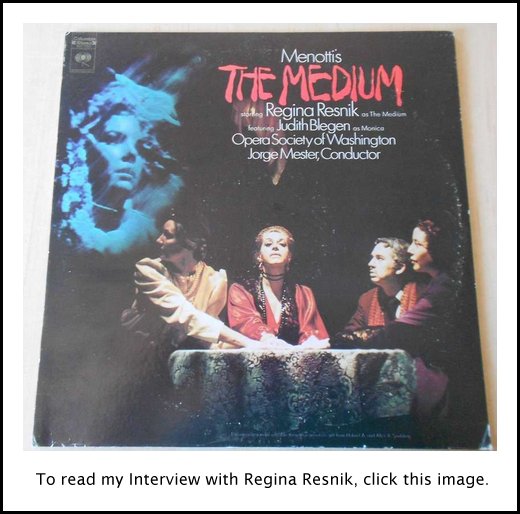

Orchestra of Mexico. His opera debut was with Salome in 1960 at the Spoleto Festival

in Italy. Since then he has conducted many of the world's leading ensembles,

including the Boston Symphony, the Detroit Symphony, and the Royal Philharmonic

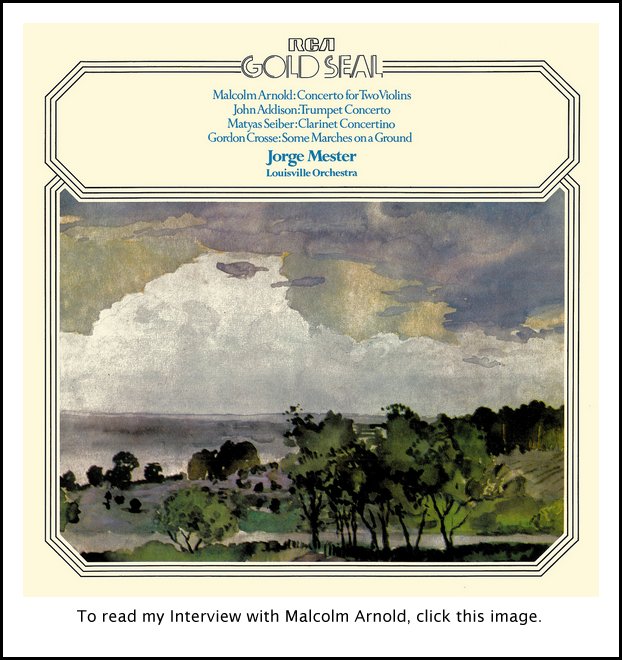

orchestras. In 1967 he became music director of the Louisville Orchestra, noted for its advocacy of new and neglected music. With this orchestra Mester made more than seventy first recordings of works by such composers as Bruch, Cowell, Crumb, Dallapiccola, Ginastera, Granados, Koechlin, Penderecki, Petrassi, Schuller, and Shostakovich. From 1969 to 1990 he was music director of the Aspen Festival and later became its conductor laureate. Mester was appointed music director of the Pasadena Symphony Orchestra in 1983, and in 1998 he added to that post the music directorship of the Mexico City Philharmonic Orchestra. A noted teacher, he was on the faculty of The Juilliard School for most of the period between 1958 and 1988. -- Names which are links refere to my interviews

elsewhere on this website. BD

|

BD: Are you able to study on the plane and in hotels?

BD: Are you able to study on the plane and in hotels? JM:

One of the secrets of conducting is the pacing, from the first rehearsal through

the performance. I’ve always been pretty comfortable with that.

I don’t think I’ve ever peaked before a performance. What surprises

orchestras is that one can go from the kind of intellectual rigor that you

have to apply to rehearsals, and suddenly make the leap at a performance to

something where they almost are in charge. There are orchestras that

can’t handle that.

JM:

One of the secrets of conducting is the pacing, from the first rehearsal through

the performance. I’ve always been pretty comfortable with that.

I don’t think I’ve ever peaked before a performance. What surprises

orchestras is that one can go from the kind of intellectual rigor that you

have to apply to rehearsals, and suddenly make the leap at a performance to

something where they almost are in charge. There are orchestras that

can’t handle that. BD: So you had to change the concerto four

times?

BD: So you had to change the concerto four

times?

BD: It seems, then, you’re much more of a populist

about all of this.

BD: It seems, then, you’re much more of a populist

about all of this. JM:

That particular piece just doesn’t speak to me, and the fact that it’s

now a bestseller and has sold a million copies doesn’t mean anything to me.

A lot of stuff that sells a million copies doesn’t mean anything to me, and

there’s a lot of stuff that doesn’t sell any copies that means a lot to

me! I don’t need to be politically correct.

JM:

That particular piece just doesn’t speak to me, and the fact that it’s

now a bestseller and has sold a million copies doesn’t mean anything to me.

A lot of stuff that sells a million copies doesn’t mean anything to me, and

there’s a lot of stuff that doesn’t sell any copies that means a lot to

me! I don’t need to be politically correct. BD: So am I to assume then that you think the technical

quality of orchestras has improved over the last forty years?

BD: So am I to assume then that you think the technical

quality of orchestras has improved over the last forty years? JM: It’s mainly joys. When you work with

American singers, there’s nothing they cannot do; also the British singers

and Australian singers. There are obviously a lot of European singers

that are wonderful, but you cannot actually put on many opera performances

in Europe without having Americans in there. They’re trained well, they

have beautiful voice production, and they are flexible, malleable and open

to good direction by the stage director as well as by the conductor.

What’s painful about opera is when you have singers of the old school who

have learned their music really badly, and then can only sing it the way they

learned it. A few do not even read music. They’re still there!

I’ve just done a production of Cavalleria

and Pagliacci with people who had

learned it wrong. Everything was wrong stylistically, and technically

with the wrong notes. They can never change it, yet they’ve had success

because they get up there and they can do it. But you get into rehearsal

and it’s not a productive situation; you cannot move and transcend and go

into some kind of new point of view. So that was not a happy experience.

JM: It’s mainly joys. When you work with

American singers, there’s nothing they cannot do; also the British singers

and Australian singers. There are obviously a lot of European singers

that are wonderful, but you cannot actually put on many opera performances

in Europe without having Americans in there. They’re trained well, they

have beautiful voice production, and they are flexible, malleable and open

to good direction by the stage director as well as by the conductor.

What’s painful about opera is when you have singers of the old school who

have learned their music really badly, and then can only sing it the way they

learned it. A few do not even read music. They’re still there!

I’ve just done a production of Cavalleria

and Pagliacci with people who had

learned it wrong. Everything was wrong stylistically, and technically

with the wrong notes. They can never change it, yet they’ve had success

because they get up there and they can do it. But you get into rehearsal

and it’s not a productive situation; you cannot move and transcend and go

into some kind of new point of view. So that was not a happy experience. JM: Yes. If it’s a brand new score, you never

know until you do it, and of course I’ve had to choose. When I was in

Louisville, I didn’t have the wonderful, comfortable experience of choosing

from among works that were commissioned, because the whole program was based

originally on choosing composers and playing the music that they wrote specifically

for that occasion. By the time I came along, the commissioning project

was no longer in existence and I had to choose from scores that were sitting

around. That’s a tough thing to do because you’re looking through these

mountains of scores and trying to decide which ones — and I’m putting this

in quotes — are “worthy” of being recorded.

JM: Yes. If it’s a brand new score, you never

know until you do it, and of course I’ve had to choose. When I was in

Louisville, I didn’t have the wonderful, comfortable experience of choosing

from among works that were commissioned, because the whole program was based

originally on choosing composers and playing the music that they wrote specifically

for that occasion. By the time I came along, the commissioning project

was no longer in existence and I had to choose from scores that were sitting

around. That’s a tough thing to do because you’re looking through these

mountains of scores and trying to decide which ones — and I’m putting this

in quotes — are “worthy” of being recorded.

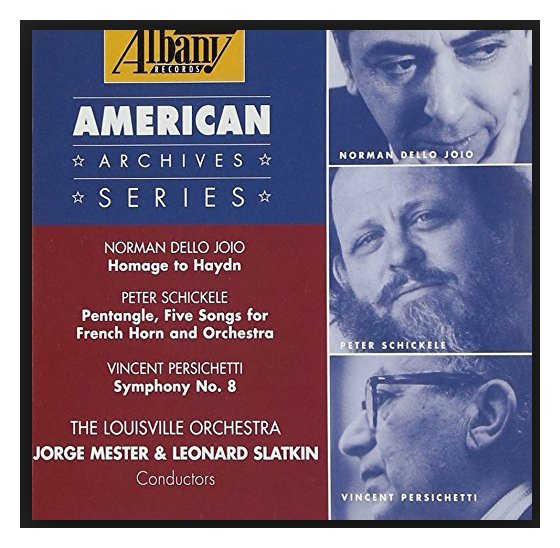

To read my Interview with Norman Dello Joio, click HERE. To read my Interview with Peter Schickele, click HERE. To read my Interview with Vincent Persichetti, click HERE. To read my Interviews with Leonard Slatkin, click HERE.

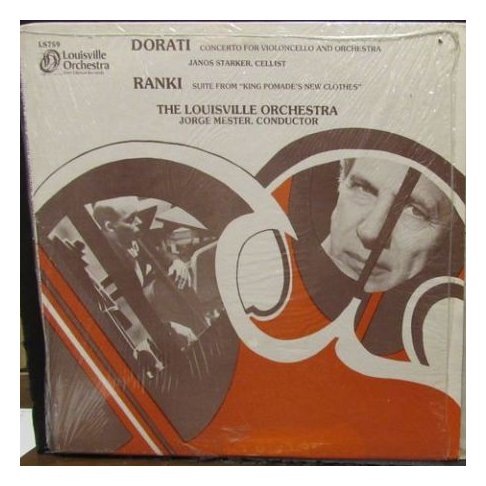

To read my Interview with Antal Dorati, click HERE. To read my Interview with Janos Starker, click HERE. To read my Interview with György Ránki, click HERE.

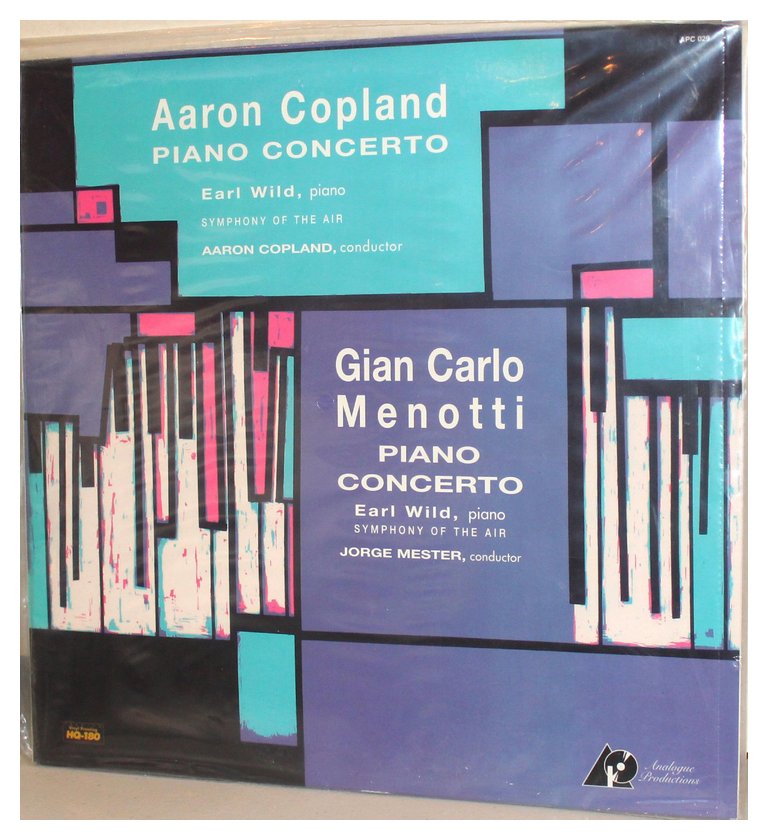

To read my Interview with Earl Wild, click HERE.

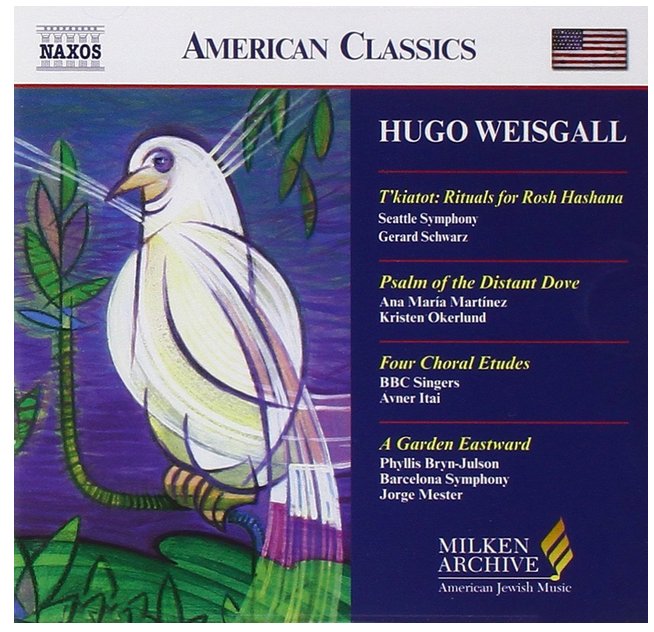

To read my Interview with Hugo Weisgall, click HERE, To read my Interview with Gerard Schwarz, click HERE. To read my Interview with Phyllis Bryn-Julson, click HERE.

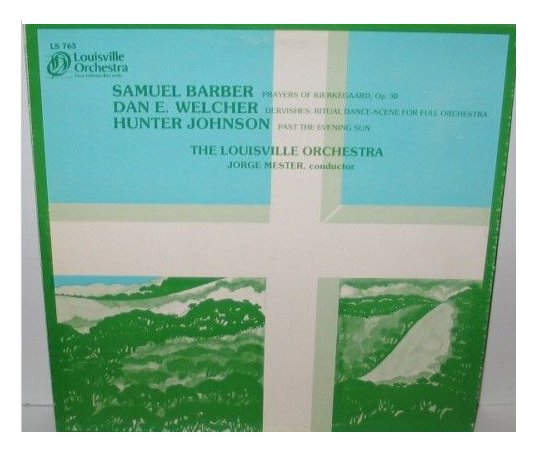

To read my Interview with Hunter Johnson, click HERE. |

This interview was recorded in a conference room at O’Hare Airport

on July 14, 1994. Portions (along with recordings) were broadcast on

WNIB the following year and in 2000. The transcription was made and

posted on this website early in 2009. More photos and links were

added at the end of 2015, and subsequently.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.