BD: Did they change it, or no?

BD: Did they change it, or no? JS: Yes! I think so, because I even found

a minimalist piece, as I told you, that I liked! [Laughs] I agree

with everything that Rorem said in that article today. He says that

he never did go through changes of style. He’s a friend of Virgil Thomson, and they always

wrote the same way right through. They didn’t run off with the Schoenberg

twelve-tone business and have to come back. He also says that the art

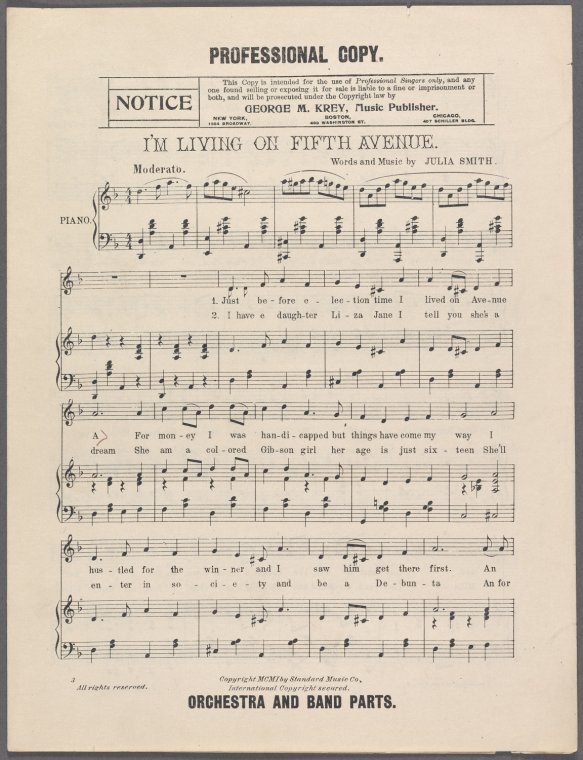

song died in 1955. I remember when that happened, all the publishers

threw out all the American art songs because they weren’t selling.

I think that must have been about the time that Elvis Presley was hitting

it big. Maybe that was the reason, because of the songs

he sang. He was a good singer, to my way of thinking, of popular music.

He really knew how to sing; he had a voice. I heard voice teachers

really think that he was just the best of all of those people that were coming

along. He had the best voice. I don’t

know exactly what it was, but the publishers just weren’t selling enough

of our songs. By word of mouth I found out that they were going to

throw those out, burn them up, so I got some of my songs and a lot of other

composers got theirs, too.

JS: Yes! I think so, because I even found

a minimalist piece, as I told you, that I liked! [Laughs] I agree

with everything that Rorem said in that article today. He says that

he never did go through changes of style. He’s a friend of Virgil Thomson, and they always

wrote the same way right through. They didn’t run off with the Schoenberg

twelve-tone business and have to come back. He also says that the art

song died in 1955. I remember when that happened, all the publishers

threw out all the American art songs because they weren’t selling.

I think that must have been about the time that Elvis Presley was hitting

it big. Maybe that was the reason, because of the songs

he sang. He was a good singer, to my way of thinking, of popular music.

He really knew how to sing; he had a voice. I heard voice teachers

really think that he was just the best of all of those people that were coming

along. He had the best voice. I don’t

know exactly what it was, but the publishers just weren’t selling enough

of our songs. By word of mouth I found out that they were going to

throw those out, burn them up, so I got some of my songs and a lot of other

composers got theirs, too.| SMITH, JULIA

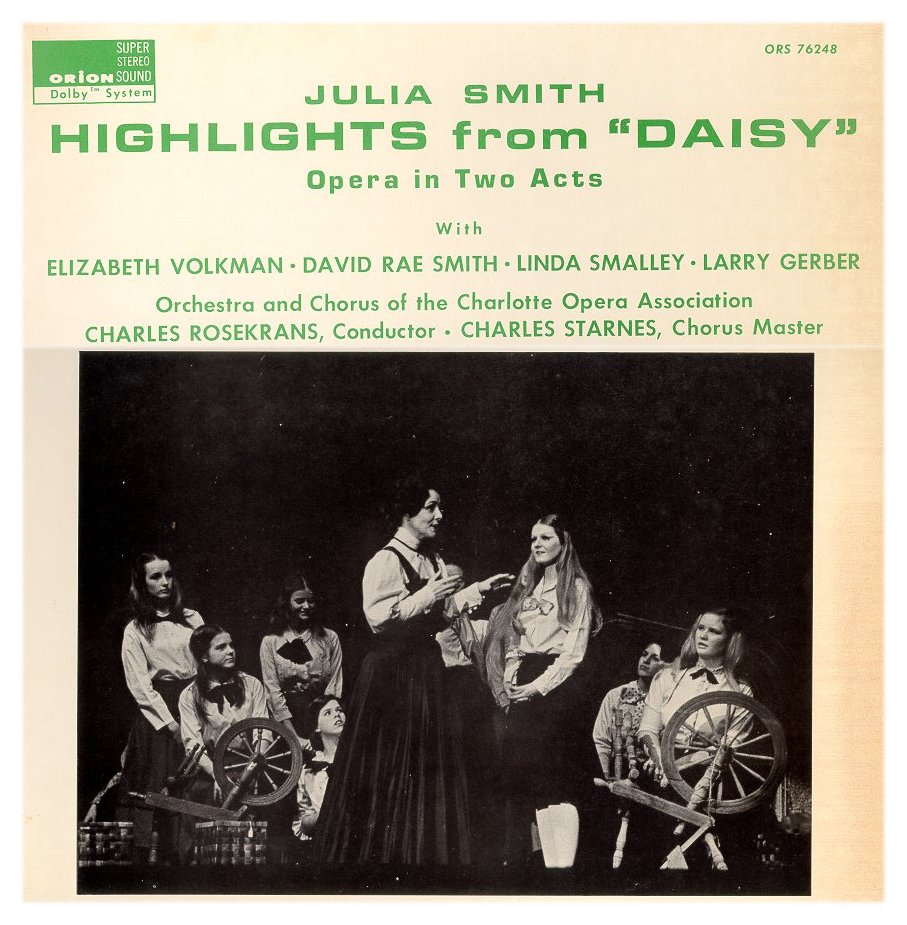

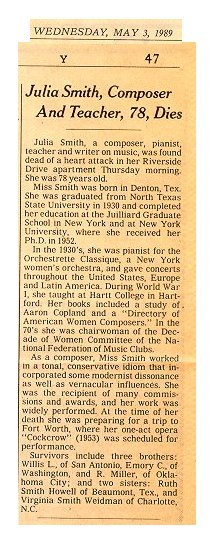

FRANCES (1905–1989). Julia Frances Smith, composer, concert pianist, author,

and advocate for women composers, was born on January 15, 1905, in Carwell,

Texas, to James Willis and Julia (Miller) Smith, who were both musical and

who encouraged their daughter's obvious musical talent. During her teens

she studied with Harold von Mickwitz at the Institute of Musical Art in Dallas.

In 1930 she earned a B.A. in music from North Texas State Teachers College

(now University of North Texas), where she composed the school's Alma Mater. She then moved to New York for further study and remained there. She studied piano and eventually composition at the Juilliard Graduate School (1932–39), where she earned a diploma. She also studied at New York University (M.A., 1933; Ph.D., 1952). From 1932 to 1942 she was pianist for the Orchestrette Classique of New York, a women's orchestra founded by Frederique Petrides. The group premiered several of her works. Smith studied composition at Juilliard after completing her master's degree at NYU, first with Rubin Goldmark and then with Frederick Jacobi. During her career she wrote in practically all musical forms for ensembles large and small. It was her success in writing in the larger forms and getting them performed, however, that set her apart from earlier women composers. By 1934 she determined to write her first opera, Cynthia Parker, in honor of the coming Texas Centennial. Although the premiere of the work was delayed until 1939, it brought her to national prominence and was only the first of six operas she wrote. Many of her works incorporate folk melodies and dance idioms within a relatively conservative, tonal harmonic palette, although she was not afraid of dissonance. The accessibility of her work to a wide audience aided the success of her compositions. On April 23, 1938, Julia Smith married Oscar A. Vielehr, an engineer and inventor who wholeheartedly supported his wife's career as a composer. Beginning in 1935 Smith took up a part-time teaching career, first at the Hamlin School in New Jersey. A few years later she taught at Juilliard (1940–42) and then as founder and head of the department of music education at Hartt School (1941–46). She also taught at Teachers College of Connecticut (1944–46). The decade of the 1950s marked the beginning of her writing career with the publication of her revised doctoral dissertation: Aaron Copland: His Work and Contribution to American Music (New York, 1955). This book, the first detailed study of this important American composer, received critical acclaim. Smith also performed numerous lecture–recitals featuring Copland's piano works in succeeding years. She later published Master Pianist: The Career and Teaching of Carl Friedberg (New York, 1963) as a tribute to her teacher at the Juilliard School. The decade of the 1950s also marked the beginning of Smith's vocal advocacy for the woman composer. In 1951 she spearheaded a New York recital of works by Marion Bauer. In the late 1960s she and Merle Montgomery planned a concert of chamber music by American women composers for the Musicians Club of New York, dedicating it to the National Federation of Music Clubs in honor of its efforts on behalf of women composers. This began her association with the NFMC and its programs. She was appointed chairman of American Women Composers, a post that led to the publication of her Directory of American Women Composers (Chicago, 1970), a pioneering work that appeared just as the women's movement of the 1970s was getting underway. She also chaired for the NFMC its Decade of Women Committee (1970–79) and in 1972 and 1973 arranged two thirteen-week series of national broadcasts of works by American composers, almost half of them women. Although her work on behalf of other composers encroached, Smith still managed to continue her own composing career. She wrote a work for the inauguration of Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965 (Remember the Alamo!) and her final opera, Daisy (1973), based on the life of Juliette Gordon Low, founder of the Girl Scouts in the United States. In the end, however, her importance as an advocate for the plight of ignored women composers may have overshadowed her own career as a composer. Smith died on April 18, 1989, in New York City while preparing to return from New York to Fort Worth for a performance of her opera Cockcrow. Her husband had preceded her in death in 1975. She was buried in the family plot in Denton. BIBLIOGRAPHY: Christine Ammer, Unsung: A History of Women in American Music, Second Edition (Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 2001). Jane Weiner LePage, Women Composers, Conductors, and Musicians of the Twentieth Century, Volume 2 (Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press, 1983). Stanley Sadie, ed., The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2d ed. (New York, Grove, 2001). Nicolas Slonimsky and Laura Kuhn, eds., Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, Centennial Edition (New York, Schirmer, 2001). -- Larry Wolz

|

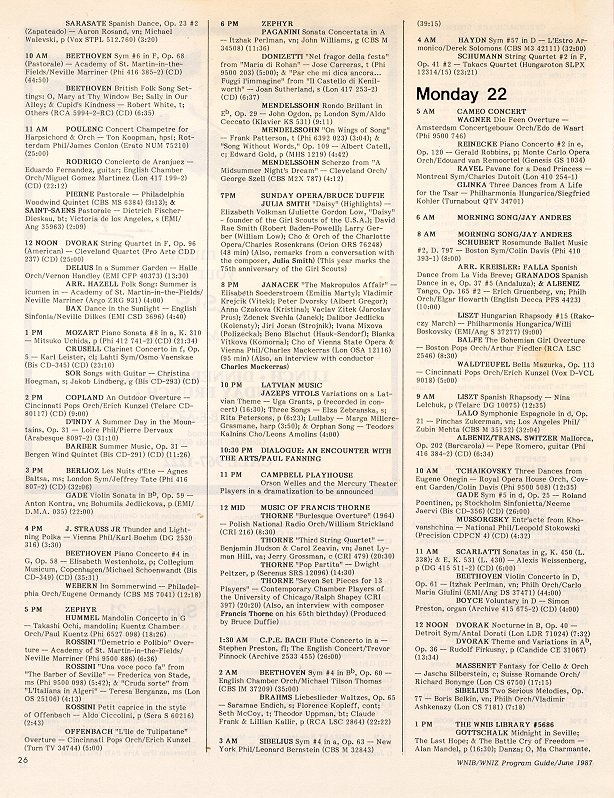

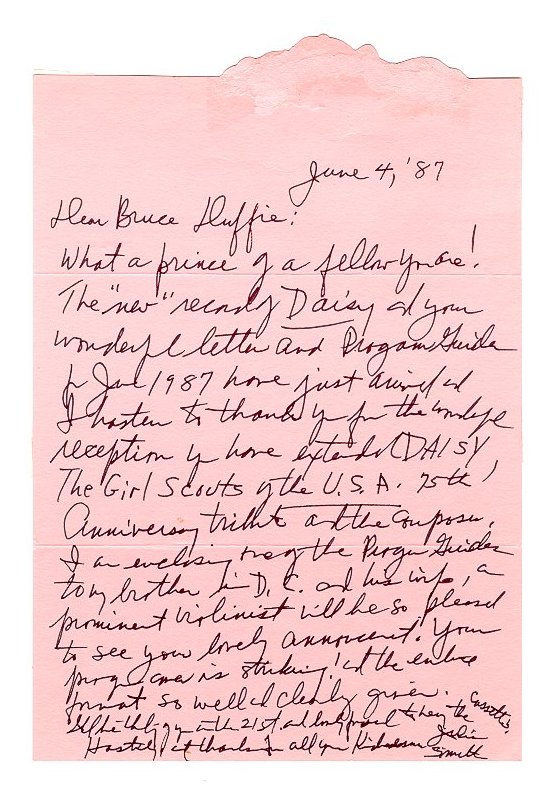

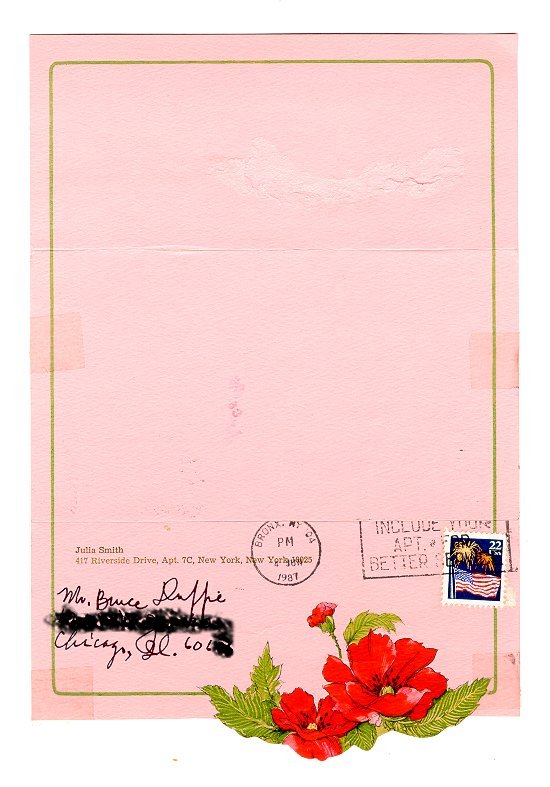

This interview was recorded on the telephone on May 3, 1987. Portions (along with recordings) were quoted from the conversation on WNIB the following month, and audio excerpts were aired with recordings in 1991 and again in 1996. A piece of her music was included as part of the in-flight entertainment package aboard Delta Airlines in 1989. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.