A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

UK: It’s very hard to say. Who’s the public?

Who do you write for? You write for yourself and you try to express

whatever ideas or feelings that you have through your medium, in our case,

music. But it would be the same for a person doing creative writing

or painting. And beyond that primary impetus and endeavor that I just

mentioned, one hopes that the music will make its way. By that, I mean

that it will reach people and there will be some follow up in terms of interest

in performing the work. That’s the sense in which I feel one reaches

the public. The public is so amorphous; [laughs] it’s huge and large

and it’s very hard to say what public, in a way. I don’t think of

it that way. I think of the problem of communication in terms of what

I write having a kind of logic — not logic in a philosophic sense, but having

a convincing character and a thrust to it. Technically you’d think

of form, contrast and all of the structural matters that the composer is

dealing with. But those elements are not really important to the listener

that much, unless it’s a programmatic piece. However, you do wish that

the ideas and the work have this kind of projection to reach the listener

in a convincing sort of way.

UK: It’s very hard to say. Who’s the public?

Who do you write for? You write for yourself and you try to express

whatever ideas or feelings that you have through your medium, in our case,

music. But it would be the same for a person doing creative writing

or painting. And beyond that primary impetus and endeavor that I just

mentioned, one hopes that the music will make its way. By that, I mean

that it will reach people and there will be some follow up in terms of interest

in performing the work. That’s the sense in which I feel one reaches

the public. The public is so amorphous; [laughs] it’s huge and large

and it’s very hard to say what public, in a way. I don’t think of

it that way. I think of the problem of communication in terms of what

I write having a kind of logic — not logic in a philosophic sense, but having

a convincing character and a thrust to it. Technically you’d think

of form, contrast and all of the structural matters that the composer is

dealing with. But those elements are not really important to the listener

that much, unless it’s a programmatic piece. However, you do wish that

the ideas and the work have this kind of projection to reach the listener

in a convincing sort of way. UK: That’s possible. I guess that records

being so pervasive now, the hi-fi people do concentrate on their libraries

pretty intently. It would seem there’s a big educational job there

to be done, in terms of people learning the true value of live performance,

in contrast to all this recorded stuff. I imagine in urban centers

like Chicago and New York, audiences do appreciate live performances, especially

of the Chicago Symphony!

UK: That’s possible. I guess that records

being so pervasive now, the hi-fi people do concentrate on their libraries

pretty intently. It would seem there’s a big educational job there

to be done, in terms of people learning the true value of live performance,

in contrast to all this recorded stuff. I imagine in urban centers

like Chicago and New York, audiences do appreciate live performances, especially

of the Chicago Symphony! BD: Is it easier to work, to set things down,

when you have more colors on your palette to choose from?

BD: Is it easier to work, to set things down,

when you have more colors on your palette to choose from? UK: I had a friend who was a producer at CBS

radio when they still had live studio orchestras. This was in the

mid-fifties. They had a program called “String Serenade” which was

on Sunday afternoons, with a live string orchestra of about twenty players.

My friend said, “Why don’t you write something for it?” I hadn’t thought

of it, and he said, “If you do, Alfredo [conductor Alfredo Antonini] will

play it.” So I wrote two of the dances. Since it was a light

music program on Sunday afternoon, I thought of writing something

in the dance form. They had the parts copied and did those two on

a broadcast. I think they had me come over and be briefly interviewed

before they were played. Then I did two more, and he did those maybe

six months later. The four seemed a little brief, so I wrote two more.

Those were never done, or if they were done I didn’t know about it.

It’s funny, but once your music gets out there you no longer control it.

Years later, two of them were recorded in London, on London Records — Round Dance and Polka. I didn’t have anything to

do with the recording. Then much, much later, I guess in the early

seventies, Paul Freeman

recorded the six of them. [Names which are links refer to my interviews

elsewhere on my website. BD]

UK: I had a friend who was a producer at CBS

radio when they still had live studio orchestras. This was in the

mid-fifties. They had a program called “String Serenade” which was

on Sunday afternoons, with a live string orchestra of about twenty players.

My friend said, “Why don’t you write something for it?” I hadn’t thought

of it, and he said, “If you do, Alfredo [conductor Alfredo Antonini] will

play it.” So I wrote two of the dances. Since it was a light

music program on Sunday afternoon, I thought of writing something

in the dance form. They had the parts copied and did those two on

a broadcast. I think they had me come over and be briefly interviewed

before they were played. Then I did two more, and he did those maybe

six months later. The four seemed a little brief, so I wrote two more.

Those were never done, or if they were done I didn’t know about it.

It’s funny, but once your music gets out there you no longer control it.

Years later, two of them were recorded in London, on London Records — Round Dance and Polka. I didn’t have anything to

do with the recording. Then much, much later, I guess in the early

seventies, Paul Freeman

recorded the six of them. [Names which are links refer to my interviews

elsewhere on my website. BD] UK: Oh, yes, often that happens! It isn’t

exactly that I don’t know it’s there; it’s a matter of what is prevalent

at a particular moment in terms of the balance or inner workings of texture.

As you know, notation is a very inadequate incomplete system, so that certain

gradations of dynamics or tempo are put down as best you can.

You indicate how fast or how loud, but it’s all relative.

So the way I might feel the passage is barely perceived by the conductor.

Or it may be a technical problem in terms of balance or range that makes

it difficult for the players, so he will work it out a particular way.

Then if it doesn’t feel right, you can speak to the conductor, or often

the conductor will either turn around or see you during the break and want

to know about certain details.

UK: Oh, yes, often that happens! It isn’t

exactly that I don’t know it’s there; it’s a matter of what is prevalent

at a particular moment in terms of the balance or inner workings of texture.

As you know, notation is a very inadequate incomplete system, so that certain

gradations of dynamics or tempo are put down as best you can.

You indicate how fast or how loud, but it’s all relative.

So the way I might feel the passage is barely perceived by the conductor.

Or it may be a technical problem in terms of balance or range that makes

it difficult for the players, so he will work it out a particular way.

Then if it doesn’t feel right, you can speak to the conductor, or often

the conductor will either turn around or see you during the break and want

to know about certain details. UK: Yes, right!

UK: Yes, right!

|

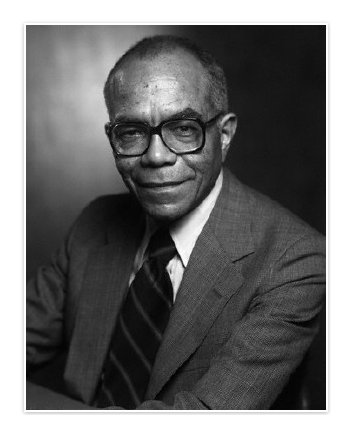

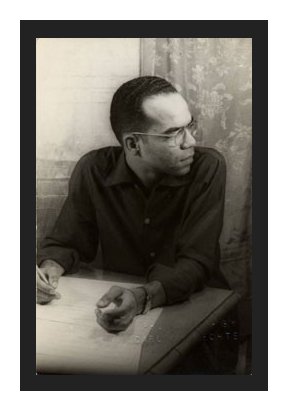

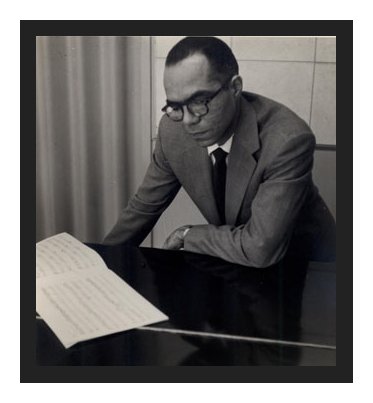

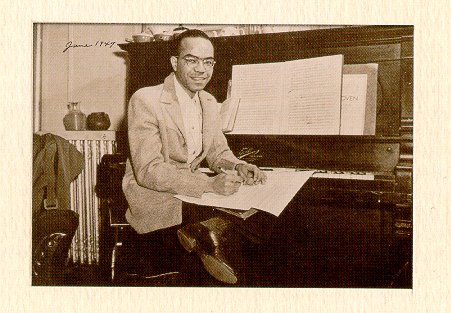

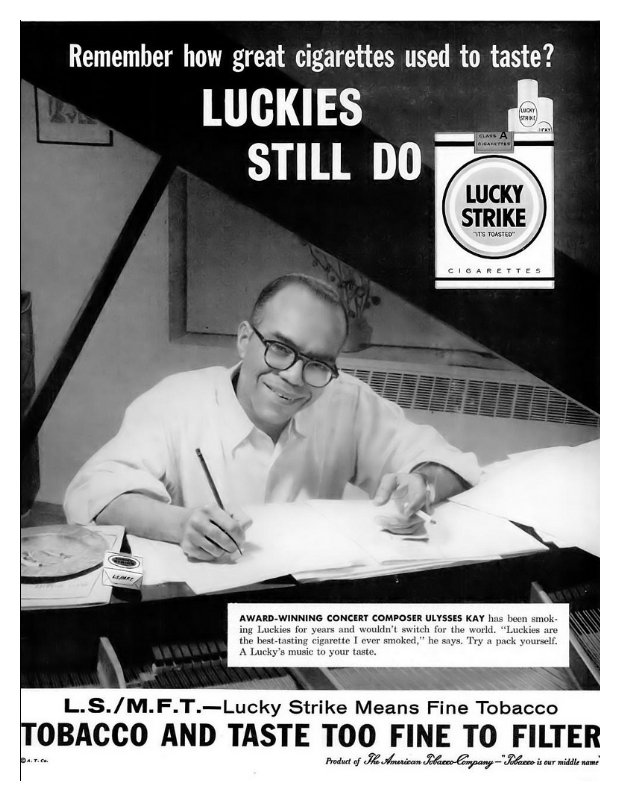

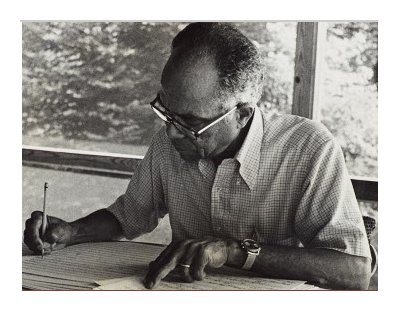

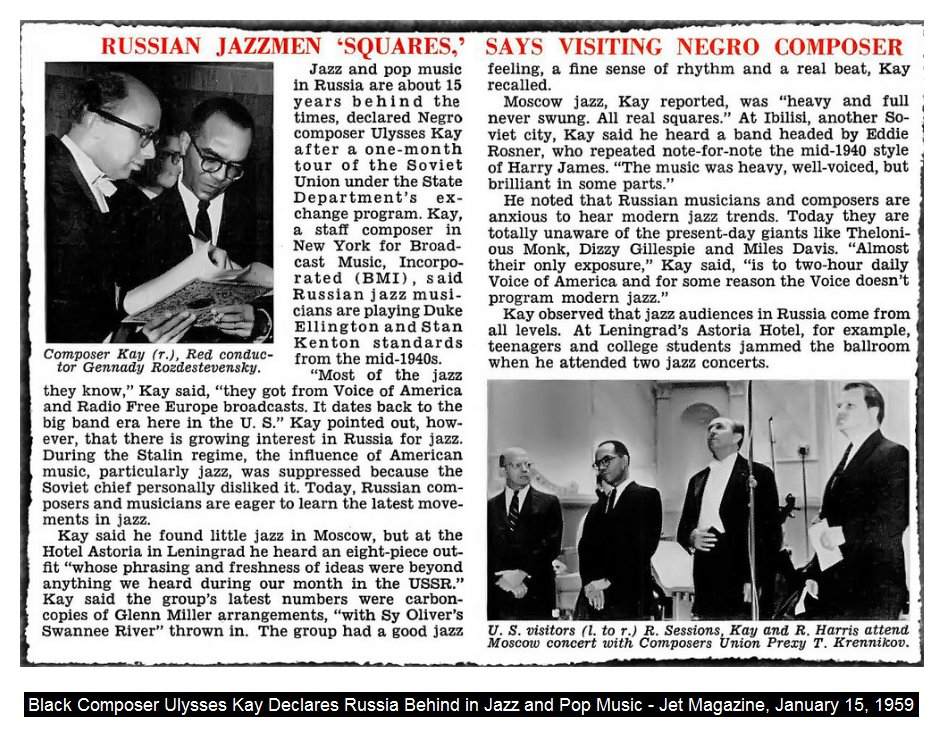

Ulysses Simpson Kay, Jr. Personal Information Born on January 7, 1917, in Tucson, AZ; died May 20, 1995, in Teaneck, NJ; son of a barber; married; children: Virginia, Melinda, and Hillary Education: University of Arizona, bachelor of music, 1938; Eastman School of Music, Rochester, NY, master's degree, 1940; further composition studies with Paul Hindemith, 1941-42; Otto Luening, 1946-49. Military/Wartime Service: Served as Musician Second Class in U.S. Naval Reserves, 1942-45. Memberships: (selected) Member, American Academy of Arts and Letters. Career Lived in Rome while studying and composing at American Academy, 1949-52; consultant, Broadcast Music Incorporated (BMI), 1953-68; traveled to Soviet Union on U.S. State Department tour, 1958; Boston University, visiting professor, 1965; University of California at Los Angeles, visiting professor, 1966-67; Lehman College, City University of New York, professor, 1968-88; named Distinguished Professor, 1972. Life's Work One of the few African Americans to have enjoyed a successful career in the rather closed-in world of academic musical composition, Ulysses Kay wrote over 135 pieces in genres ranging from solo piano works to full-length opera. Kay was notable for his attitude toward the use of black idioms such as jazz and the spiritual in a classical context: he used such styles when he felt them to be appropriate, but was not particularly identified with the strong African-American influences heard in the music of composers such as William Grant Still and George Gershwin. After composing his opera Frederick Douglass (1991), Kay explained (according to the Washington Post) that "I wasn't composing operas to prove anything. I write out of interest, rather than trying to take on the cause of blackness or whatever. Ulysses Simpson Kay was born in Tucson, Arizona, on January 7, 1917. His family was especially musical even compared with the often music-friendly environments in which other famous musicians grew up: his mother and sister played the piano, and his father was a barber who occasionally made up original songs to entertain his family. Most important of all was Kay's uncle, the famed New Orleans cornetist and jazz bandleader Joe "King" Oliver. Despite his own band-instrument background, Oliver steered Kay toward formal piano lessons when he started to show an interest in music. Kay did take up the saxophone later, playing in the school marching band at Tucson Senior High School and sometimes joining jazz ensembles on the side. A small Western college town, Tucson was relatively free of the strict educational segregation imposed in the southeastern states; Kay was able to enroll at the University of Arizona in 1934, and his classical background was helpful as he completed courses for a public school music major. It was at Arizona that Kay first studied music theory and composition, and he was especially impressed by the music of the modern Hungarian compoer Bela Bartók. The so-called "dean of African-American composers," William Grant Still, heard of Kay's work and encouraged his compositional efforts. The subtle rhythms and brilliant orchestrations of Bartók's music would leave their mark on Kay's own compositions, but a new set of influences was added after Kay won a scholarship to the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. Eastman's graduate program had shaped the careers of several of the leading American composers of the day, and Kay studied with the crowd-pleasing symphonic composer Howard Hanson. One piece performed while he was at Eastman, the Danse Calinda, was inspired by the African-flavored dances that survived in New Orleans through the era of slavery, but in most of his other works Kay followed the cool, balanced "Neo-Classical" style of another important teacher, the transplanted German Paul Hindemith, with whom Kay worked for two summers at the Tanglewood music festival in Massachusetts. Kay was able to continue composing during a three-and-a-half-year stint in the U.S. Navy Reserves during World War II. Toward the end of the war his compositions began to gain mainstream performances and critical praise. The New York Philharmonic performed his Of New Horizons at an outdoor concert in 1944. His Suite for Orchestra of 1945 won a prize from the young BMI music-licensing organization, and two years later Leonard Bernstein conducted the New York Philharmonic in the premiere of Kay's Short Overture. By that time Kay had enrolled at Columbia University for further study. He spent a year in Europe on a scholarship in 1947 and 1948. After his return Kay celebrated two happy events: he married his wife Barbara in 1949 (the couple raised three daughters), and that year he won the prestigious Prix de Rome, enabling him to live in Italy and study for three years. Kay wrote several large orchestral pieces while he was there, and his Concerto for Orchestra was performed by an orchestra in Venice. He also won a Fulbright Scholarship in 1950. Despite these sterling credentials, however, Kay only found work outside of academia when he finally came back to the United States; he was employed for 15 years as a consultant for BMI. Kay wrote two short operas in the mid-1950s, and in 1958 he joined three other leading composers on a U.S. State Department-sponsored cultural exchange tour of the Soviet Union. The Choral Triptych of 1962 remains one of Kay's most widely performed pieces. After the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, Kay wrote the score for a televised Kennedy tribute, An Essay on Death. In the mid-1960s he took visiting professorships at Boston University, Bucknell University, and the University of California at Los Angeles, and in 1968 he won a permanent appointment at Lehman College, a unit of the City University of New York. Prestigious commissions, including one from Washington, D.C.'s National Symphony (Western Paradise, for narrator and orchestra, 1975), flowed Kay's way in the 1970s. By that time Kay had forged his mature style, which, according to New Grove Dictionary of American Music contributor Eileen Southern, "is characterized by taut but warm melodies, complex polyphony, vibrant harmonic and orchestral coloring, and rhythmic diversity." Nicolas Slonimsky, writing in Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, noted that Kay avoided what Slonimsky called "ostentatious ethnic elements." In fact, though, two of the major works of Kay's later career took up African-American themes and necessarily incorporated spirituals and other examples of black music. Both of these were operas: Jubilee (1976, commissioned by Opera/South of Jackson, Mississippi) was based on Margaret Walker's novel of the same title, set in the time of slavery and its aftermath, and Kay's final major work, Frederick Douglass (1991), a musical biography of the abolitionist writer and ex-slave. After receiving numerous honorary doctorates and other academic honors, Kay retired from his Lehman College position in 1988. Kay died at his home in Teaneck, New Jersey, from the effects of Parkinson's Disease on May 20, 1995. He had done much to inspire a younger generation of African-American classical composers and undeniably blazed trails for them in the academic world, through whose doors almost no African-American composers had passed before. But several of his obituaries noted the contrast between the nearly universal praise his music had received and its relative obscurity. "He was as talented a musician as a Bernstein or a Copland," musical scholar Hildred Roach told the Washington Post. But, said Roach, "he never got the publicity." Awards Selected: Prix de Rome, 1949; Fulbright Foundation grant, 1950; Guggenheim Fellowship, 1964; resident fellowship, Bellagio Study and Conference Center, Como, Italy, 1982. |

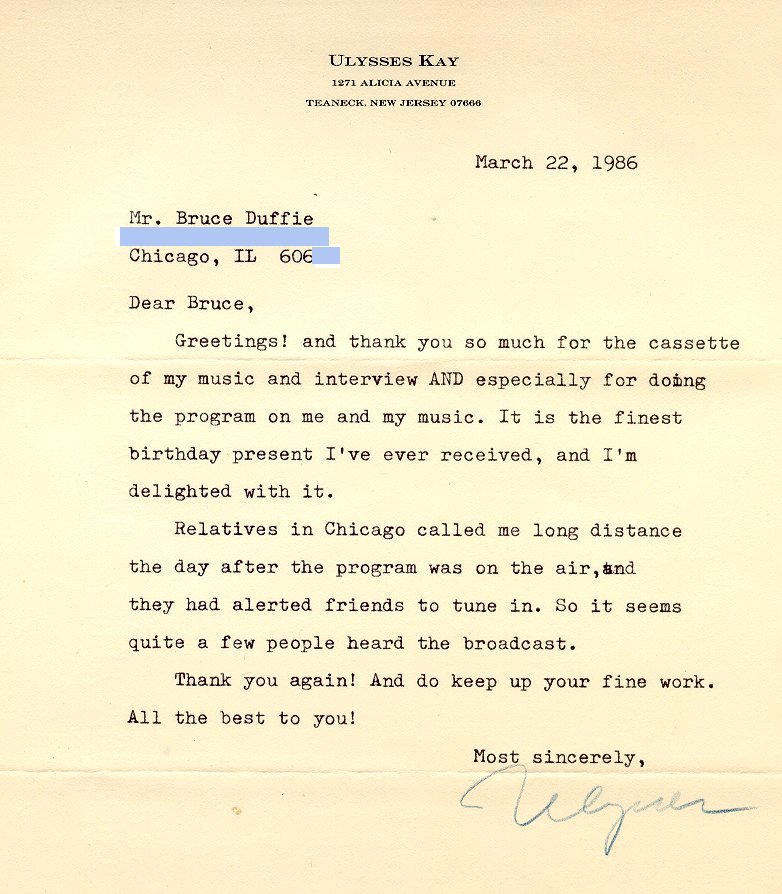

This interview was recorded on the telephone on July 20, 1985.

Portions were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1986, 1987, 1989, 1992

and 1997. The transcription was made and posted on this website in

2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.