|

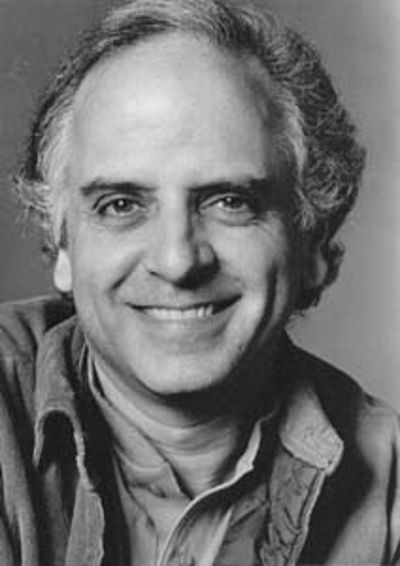

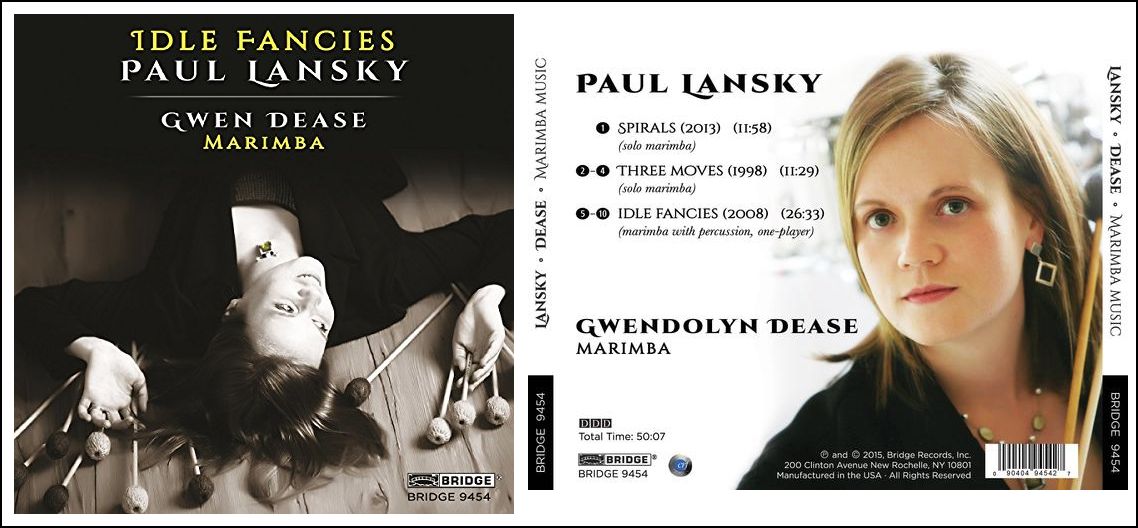

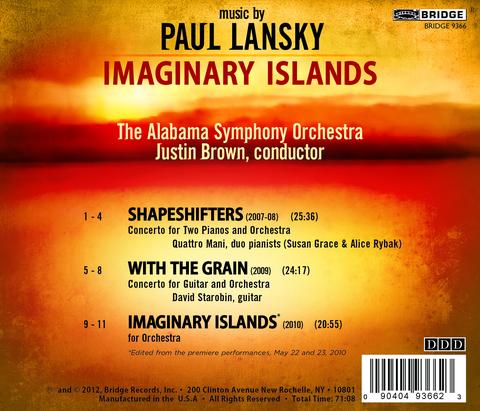

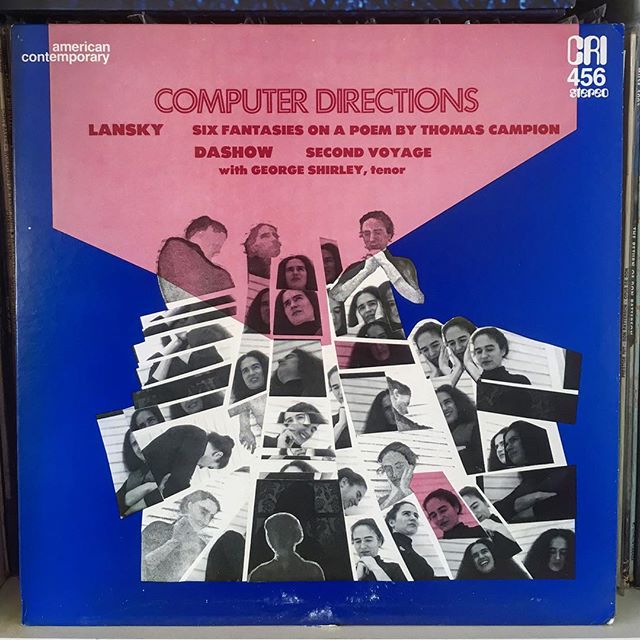

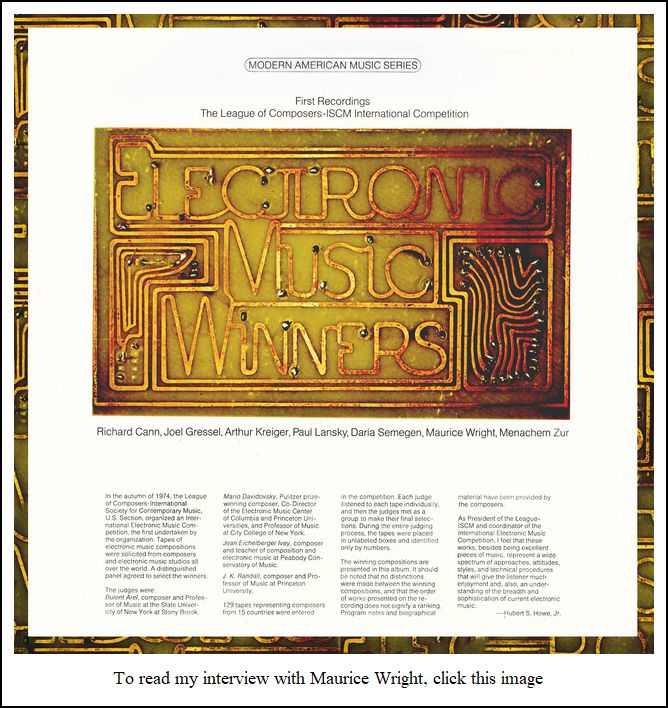

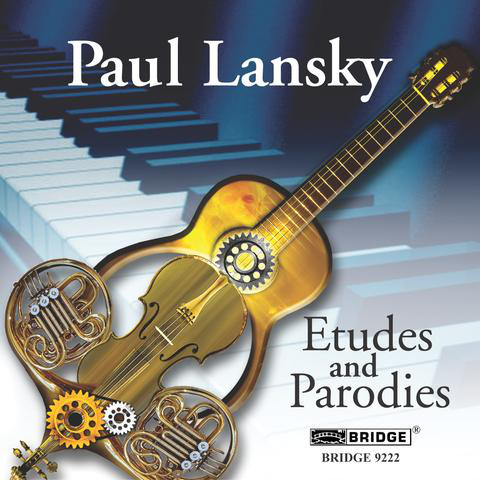

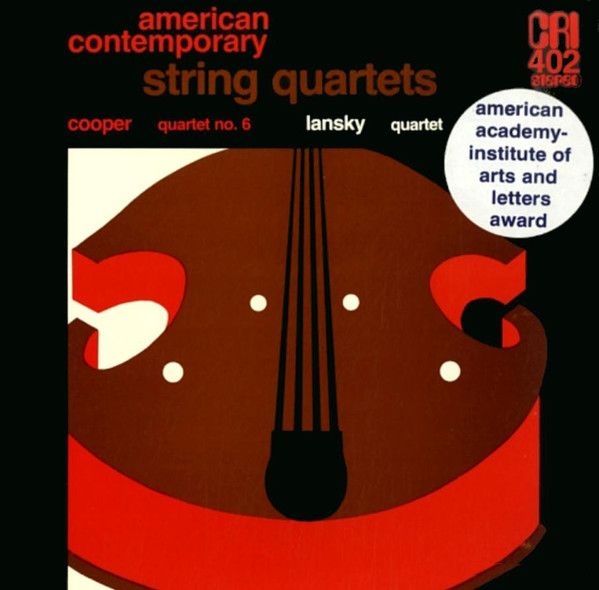

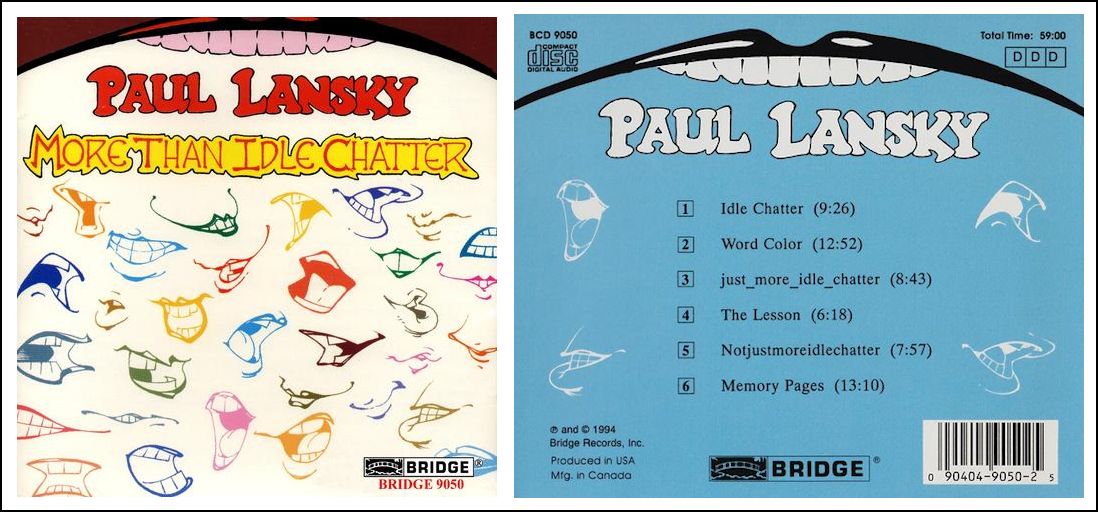

Until the mid-1990’s the bulk of Lansky’s work was in computer music, and he has long been recognized as one of its pioneers. In 2002 he was the recipient of a lifetime achievement award from SEAMUS (the Society for Electroacoustic Music in the United States) and in 2000 he was the subject of a documentary made for European Television’s ARTE network, My Cinema for the Ears, directed by Uli Aumueller (now available on DVD). His music is well represented on recordings, and played and broadcast widely. Numerous dance companies have choreographed his works, including Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane, the Eliot Feld and New York City Ballets. His piece Notjustmoreidlechatter is included in the Norton Anthology accompanying the widely used music appreciation text, The Enjoyment of Music. He has received awards and commissions from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Guggenheim, Koussevitsky and Fromm Foundations, Lila Wallach/Reader’s Digest, ASCAP, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, among others. During the mid 1990’s he began to turn more intensively towards instrumental music, writing works for performers such as Nancy Zeltsman and David Starobin. His work, Three Moves for Marimba, written for and recorded by Zeltsman, has been gaining wide recognition as one of the most challenging and rewarding pieces for this instrument. (Zeltsman devotes a chapter of her recent book on four-mallet marimba playing to the work.) A recent percussion quartet, Threads, written for the Sō Percussion ensemble has been recorded and widely performed by that group as well as by many college and university ensembles. Other percussion pieces include Idle Fancies, Songs of Parting (baritone, guitar, percussion), Spirals for marimba and Travel Diary for percussion duo. His trio for horn violin and piano, Etudes and Parodies’, written for William Purvis, was the winner of the 2005 International Horn Society Competition. The two-piano team Quattro Mani has recorded his piece It All Adds Up. In 2008 the Alabama Symphony and Quattro Mani commissioned and premiered his two-piano concerto, Shapeshifters. Lansky was composer in residence the Alabama Symphony for the 2009-2010 season, during which time they performed his orchestral works, including With the Grain, a guitar concerto written for David Starobin and commissioned by the Fromm Foundation, Shapeshifters, and Imaginary Islands commissioned by the orchestra. A CD of his orchestral music was released on Bridge Records in 2012 including these pieces. Recent projects include a joint commission by the Library of Congress and the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center for the wind quintet The Long and Short of It. Percussion music has been a dominant focus in recent years. In addition to Threads and Travel Diary, recent works involving percussion include Springs for percussion quartet, Partita for guitar and percussion, Horizons for piano, cello, and percussion, Textures for two pianos and two percussionists, Five Views of an Unfamiliar Tune for solo percussion and chamber orchestra, and Touch and Go for solo percussion and wind ensemble Lansky’s music eschews attempts to ‘break new ground’, and instead

relies heavily on an approach toward tonality and harmony that references

musical traditions of various kinds, from Machaut to Stravinsky. His string

quartet, Ricercare Plus, is based on concepts of counterpoint

and part-writing from early Baroque and Renaissance music. His horn trio,

Etudes and Parodies, refers to various music well-known to

horn players. His choral piece, Folk-Tropes, draws heavily on

Appalachian folk traditions. Many works, such as Three Moves for Marimba,

draw on jazz and popular music. Coincidentally, the English rock band

Radiohead used a sample from Lansky’s first computer piece, mild und

leise as a basis for their 2000 song Idioteque. -- Biography from the Carl Fischer Music website

|

Bruce Duffie: You’re both a professor of music and a composer.

How do you divide your time between those two?

Bruce Duffie: You’re both a professor of music and a composer.

How do you divide your time between those two? BD: Have you then sold some of it?

BD: Have you then sold some of it? BD: We have been talking about your compositional

life. You teach theory and composition, also?

BD: We have been talking about your compositional

life. You teach theory and composition, also? BD: Do you know when you start how long the piece is going

to run?

BD: Do you know when you start how long the piece is going

to run? BD: Will you ever write anything without

electronics anymore?

BD: Will you ever write anything without

electronics anymore? PL: [Thinks a moment] I have a

good angle on that. My particular view at this point, today, might

not be true tomorrow, but it’s certainly been true for the past couple

of years, and that is the extent to which the piece is able to project

to me a very interesting sense of somebody being able to do something.

This is a complicated angle, because it allows me to view the piece

much more in terms of human effort than in the abstract. I move away

from the point of view which looks at a piece as an abstract entity, and

forget about the individual who is doing it. The interesting thing

about this is that it ties together perceptions of a lot of different

kinds of art. For example, children’s art can enter the picture

in an interesting way in these terms. When I look at children’s art,

I don’t look at it as immature grown-up art. I look at children’s

art as a product of children’s activities. When I look at the Jupiter

Symphony, I’m blown away by the utter genius and craftsmanship, but

I’m also interested in Mozart the composer. A lot of twentieth-century

art and a lot of twentieth-century music becomes much more accessible

to me in these terms. This is different point of view than is espoused

by others. For a long time, my feeling has been that it’s not that

difficult to write a competent piece of music. Anybody with enough

time and effort can become a competent composer. We were talking about

learning composition, and my point of view was that learning to compose

means, more than anything else, looking into your own resources and seeing

what it is that you really have to offer, and what it is you really want

to deliver. Some people don’t really feel that it’s what they want

to deliver, but they want to be composers. My sense of most of these

people is that they write pieces that I’m just not that interested in listening

to, but very often I’ll listen to a piece which may be a failure.

If a piece all of a sudden just falls apart in the middle, it doesn’t make

sense, but it may interest me a lot more because of the kinds of things that

the composer is trying to do, more than a piece which very successfully goes

from beginning to the end and ties up all the loose ends. So greatness,

in that sense, has a lot more to do with how successfully the composer really

is able to package and sell some inner vision. It doesn’t have that

much to do with invertible counterpoint.

PL: [Thinks a moment] I have a

good angle on that. My particular view at this point, today, might

not be true tomorrow, but it’s certainly been true for the past couple

of years, and that is the extent to which the piece is able to project

to me a very interesting sense of somebody being able to do something.

This is a complicated angle, because it allows me to view the piece

much more in terms of human effort than in the abstract. I move away

from the point of view which looks at a piece as an abstract entity, and

forget about the individual who is doing it. The interesting thing

about this is that it ties together perceptions of a lot of different

kinds of art. For example, children’s art can enter the picture

in an interesting way in these terms. When I look at children’s art,

I don’t look at it as immature grown-up art. I look at children’s

art as a product of children’s activities. When I look at the Jupiter

Symphony, I’m blown away by the utter genius and craftsmanship, but

I’m also interested in Mozart the composer. A lot of twentieth-century

art and a lot of twentieth-century music becomes much more accessible

to me in these terms. This is different point of view than is espoused

by others. For a long time, my feeling has been that it’s not that

difficult to write a competent piece of music. Anybody with enough

time and effort can become a competent composer. We were talking about

learning composition, and my point of view was that learning to compose

means, more than anything else, looking into your own resources and seeing

what it is that you really have to offer, and what it is you really want

to deliver. Some people don’t really feel that it’s what they want

to deliver, but they want to be composers. My sense of most of these

people is that they write pieces that I’m just not that interested in listening

to, but very often I’ll listen to a piece which may be a failure.

If a piece all of a sudden just falls apart in the middle, it doesn’t make

sense, but it may interest me a lot more because of the kinds of things that

the composer is trying to do, more than a piece which very successfully goes

from beginning to the end and ties up all the loose ends. So greatness,

in that sense, has a lot more to do with how successfully the composer really

is able to package and sell some inner vision. It doesn’t have that

much to do with invertible counterpoint. PL: There’s a very interesting change that’s coming

about, and I don’t know what to make of it. It’s going to have a

very serious, very strong effect on the future. The fundamental causes

of the change are the availability of records and TV. I came to

early maturity in the early ’60s, and even in my

generation, music was not that easy to get. If there was something

you really liked, you could find a record of it sometimes, but sometimes

you had to search for a good recording of Mozart’s Seventeenth Piano

Concerto. I remember more than once looking around to find some

Bach, or early Webern, or Schoenberg, or something that was hard to get.

Then getting the score of it was a big event, too. Lots of interesting

things were hard to get. Over the past twenty years or so, it’s become

so easy for students to get all kinds of music, so their whole view of music,

and their relation to it is changing radically. If you look at students’

libraries, they’re mostly rock ’n’ roll, but still lots of Princeton students

will have a number of jazz items. They’ll also have a number of classical

music items, such as Brahms, and they’ll have a lot of ethnic music.

They’ll have a lot of music from Indonesia, and a lot of gamelan music.

I’m talking about the really active listeners, not about the average student.

I’m talking about the students who are music freaks. They’ll spend

a long time listening, and will go from listening to gamelan music to Brahms,

to Philip Glass, or

Steve Reich, or Schoenberg.

They’ll sort of jump from one thing to another, and I can’t but help think

that this kind of rapid alternation of different musical cultures, and

different ways of thinking about music is going to have a very serious

effect on the kinds of roles that music plays. I won’t venture a value

judgment about this because I don’t think there’s any way to tell what the

meaning of it is. But I certainly think that this kind of availability

is extremely significant. Also, there is one aspect to it which is

problematic, and is probably going to be serious, and that is the extent

to which they use music not as a direct medium, but as an indirect medium.

In other words, they put it on just to fill the voids, and they put it on

because they want to have some sound to color their environment. I

think this is very, very, very troublesome, and here again, I don’t know

what to make of it. I don’t know whether this is going to lead to people

who can’t listen to music directly, who can’t really engage themselves in

music, because it's perfectly conceivable that it could have the opposite

effect — that it could, in fact, lead to a

generation of people who can listen. In other words, you don’t really

know.

PL: There’s a very interesting change that’s coming

about, and I don’t know what to make of it. It’s going to have a

very serious, very strong effect on the future. The fundamental causes

of the change are the availability of records and TV. I came to

early maturity in the early ’60s, and even in my

generation, music was not that easy to get. If there was something

you really liked, you could find a record of it sometimes, but sometimes

you had to search for a good recording of Mozart’s Seventeenth Piano

Concerto. I remember more than once looking around to find some

Bach, or early Webern, or Schoenberg, or something that was hard to get.

Then getting the score of it was a big event, too. Lots of interesting

things were hard to get. Over the past twenty years or so, it’s become

so easy for students to get all kinds of music, so their whole view of music,

and their relation to it is changing radically. If you look at students’

libraries, they’re mostly rock ’n’ roll, but still lots of Princeton students

will have a number of jazz items. They’ll also have a number of classical

music items, such as Brahms, and they’ll have a lot of ethnic music.

They’ll have a lot of music from Indonesia, and a lot of gamelan music.

I’m talking about the really active listeners, not about the average student.

I’m talking about the students who are music freaks. They’ll spend

a long time listening, and will go from listening to gamelan music to Brahms,

to Philip Glass, or

Steve Reich, or Schoenberg.

They’ll sort of jump from one thing to another, and I can’t but help think

that this kind of rapid alternation of different musical cultures, and

different ways of thinking about music is going to have a very serious

effect on the kinds of roles that music plays. I won’t venture a value

judgment about this because I don’t think there’s any way to tell what the

meaning of it is. But I certainly think that this kind of availability

is extremely significant. Also, there is one aspect to it which is

problematic, and is probably going to be serious, and that is the extent

to which they use music not as a direct medium, but as an indirect medium.

In other words, they put it on just to fill the voids, and they put it on

because they want to have some sound to color their environment. I

think this is very, very, very troublesome, and here again, I don’t know

what to make of it. I don’t know whether this is going to lead to people

who can’t listen to music directly, who can’t really engage themselves in

music, because it's perfectly conceivable that it could have the opposite

effect — that it could, in fact, lead to a

generation of people who can listen. In other words, you don’t really

know.

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 26, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1994; and on WNUR in 2003, and 2013. A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the Oral History of American Music archive at Yale Univeristy. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.