Frank Abbinanti is recognized

as one of the prime movers in Chicago's contemporary music scene.

Abbinanti's first instrument was trombone, but he later switched

to piano. In 1972, Abbinanti and his wife Ruth founded the Modern Music

Workshop, a group devoted to giving concerts of contemporary music at

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and playing the lecture circuit

on college campuses. During those years, Abbinanti also maintained a full

course of musical study, taking piano with Frederic Rzewski and composition

with Richard Teitelbaum, and later, Ralph Shapey.

Like many young composers who studied music in the serial-academic

environment of the 1970s, Abbinanti developed a severe case of new music

burnout, and although he and Shapey remained friends, Abbinanti dropped

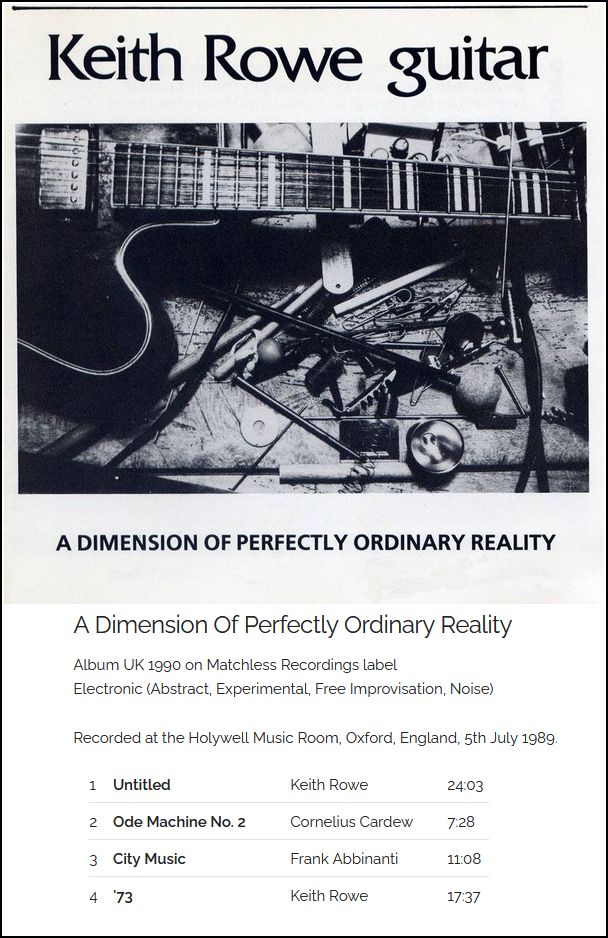

out of music for several years. The accidental death of Abbinanti's friend

and English composer Cornelius Cardew proved the event that gradually brought

Abbinanti back into the realm of music. In 1983, he organized a memorial

concert for Cardew that was both well received and the subject of some media

attention.

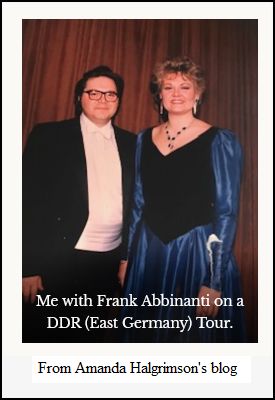

By 1985, Abbinanti was touring Europe as a pianist/composer, both

with his own works and as a representative interpreter of the works of

Chicago-based composers. With composer Peter Gena, Abbinanti co-founded

Interarts Chicago, Inc., booking many of the key artists working within

the European avant-garde into Chicago venues. In 1989, Abbinanti's commissions

began to pick up, and he composed the first of his major vocal works, cantata

immigrant, for the Polish women's chorus the Lira Singers. He has since

composed a wealth of chamber operas, cantatas, piano music, and many chamber

works, ranging from such pieces as Kobiety, koty i dzieci (women

who give birth while in prison) for solo oboe to his massive, three-hours-long

Cancion scored for cello ensemble.

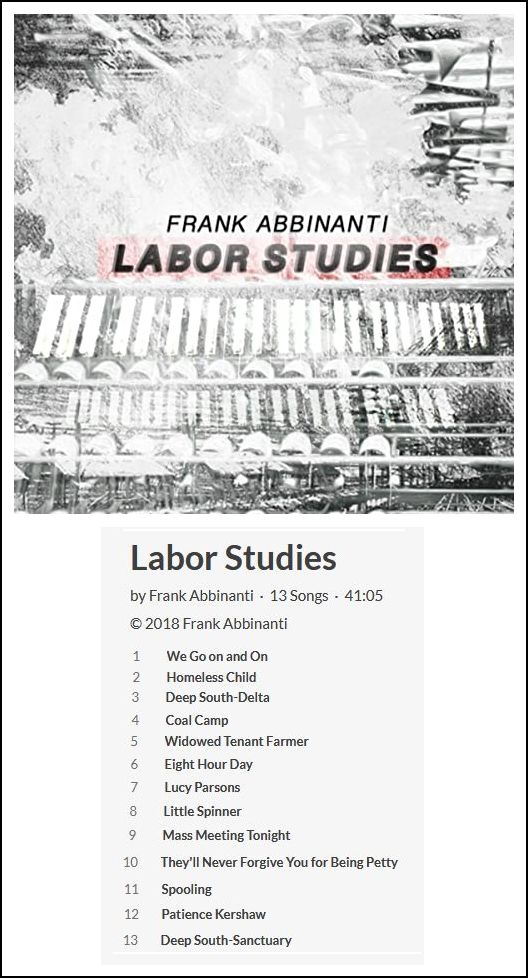

Many of Abbinanti's works are political in nature and he seldom

chooses to express himself in abstract musical terms. He has written string

quartets that bear the names of towns or nations where there is considerable

political unrest, such as East Timor, Rwanda, and Soweto. His titles

are colorful and unique, for example the flourishing of black roosters

for string quartet, Vertical Tone Pig, and The First Appearance

of Hallucinogenic Mushrooms into Cuba (both for piano). His piece The

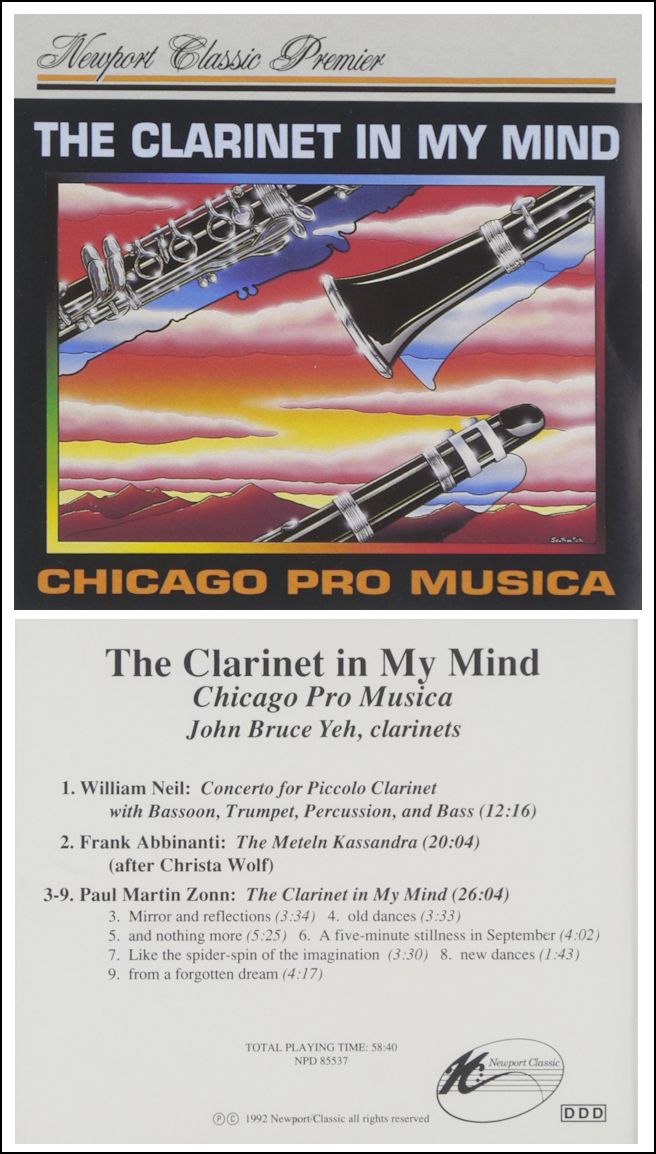

Meteln Kassandra, written for the chamber ensemble Chicago Pro Musica,

was been recorded by that group, and has garnered a fair amount of positive

critical attention.

Since 1998, Abbinanti has served as a lecturer at the University

of Chicago, but is still something of an academic "outsider". Nonetheless,

he is acclaimed as a maverick by many younger Chicago-based composers.

Clearly Abbinanti is a composer who prefers to do things his own way --

whether it's performing his hour-long piano work Paraphrase on the opera

Industrial Romance at an international festival, or playing euphonium

in the local Banda Napoletana for Italian feasts held in Chicago during

the summertime -- he is a composer at ease in both worlds.

Frank Abbinanti

(b. November 26, 1949, Chicago, Illinois).

American composer of mostly chamber, vocal and piano works that have been performed in Europe and North America; he is also active as a pianist and trombonist.

Mr. Abbinanti studied trombone privately with Frank Crisafulli (of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra) in Chicago from 1964–68, on a scholarship, and studied piano at the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago. He then studied composition and performance art with Richard Teitelbaum and piano with Frederic Rzewski at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, where he earned his BA and served as an assistant to both. He later studied composition with Ralph Shapey at the University of Chicago and studied composition privately with Ben Johnston in Chicago in 1984–85.

As a soloist, he has premièred many works for euphonium, piano, trombone, and tuba. In addition, he has played euphonium in the Banda Napoletana in Chicago.

He is also active in other positions. He co-founded with his wife, the flutist Ruth Abbinanti, the Modern Music Workshop at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign in 1972. He has organised a memorial concert to Cornelius Cardew and has supervised the production of events for numerous soloists. He served as music advisor to the Italian Cultural Consulate in Chicago in the early 1990s and as assistant conductor to the Citywide Orchestra in Chicago from 1991–95. In addition, he hosted the NEMO Festival in Chicago in 1997, with Pierre Boulez as advisor and performances by Ensemble Modern. He is a member of the board of directors of the Echo Performing Arts Orchestra, a nonprofit organisation in California. He has written several articles, as well as the book Dialogues, creating music (2005, Frog Peak Music).

He taught as a seminar lecturer at the University of Chicago from 1998–2004. He has also lectured throughout the USA, as well as in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain.

His primary publisher is Frog Peak Music.

BD: Do you try to convey all of this in both the music

and the text?

BD: Do you try to convey all of this in both the music

and the text?

BD: Especially this country with its vast resources.

BD: Especially this country with its vast resources.