A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

Julianne Baird (born December 10, 1952) has been hailed as "one of the most extraordinary voices in the service of early music that this generation has produced. She possesses a natural musicianship which engenders singing of supreme expressive beauty" (New York Times). She maintains a busy concert schedule of solo recitals and performances of baroque opera and oratorio. Ms. Baird has also appeared as soloist with many major symphony orchestras including the Cleveland Orchestra under Christoph von Dohnanyi, the Brooklyn Philharmonic under Lukas Foss, the New York Philharmonic under Zubin Mehta and, the Philadelphia Orchestra. Her seasonal New York City performances as soprano soloist in Handel's Messiah continued in 2009 with Musica Sacra in Carnegie Hall, has consistently won praise from the New York Times. James R. Oestreich, in his comprehensive survey of New York performances of Handel's Messiah recently concluded with special praise for Julianne Baird's interpretative skills: "in that respect, Ms. Baird remains the model." Most recently Anthony Tommasini wrote: "She is an admired exponent of early music and sang with focused sound and grace." (New York Times, Dec 2009). Julianne Baird's performances include appearances at the International

Lufthansa Festival in London in solo cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach

and at Tanglewood's Ozawa Hall in the Mozart Requiem, Bach's

Magnificat in Bach's own Thomaskirche in Leipzig,

and at the International Wroclaw Festival of Song in Warsaw. With over

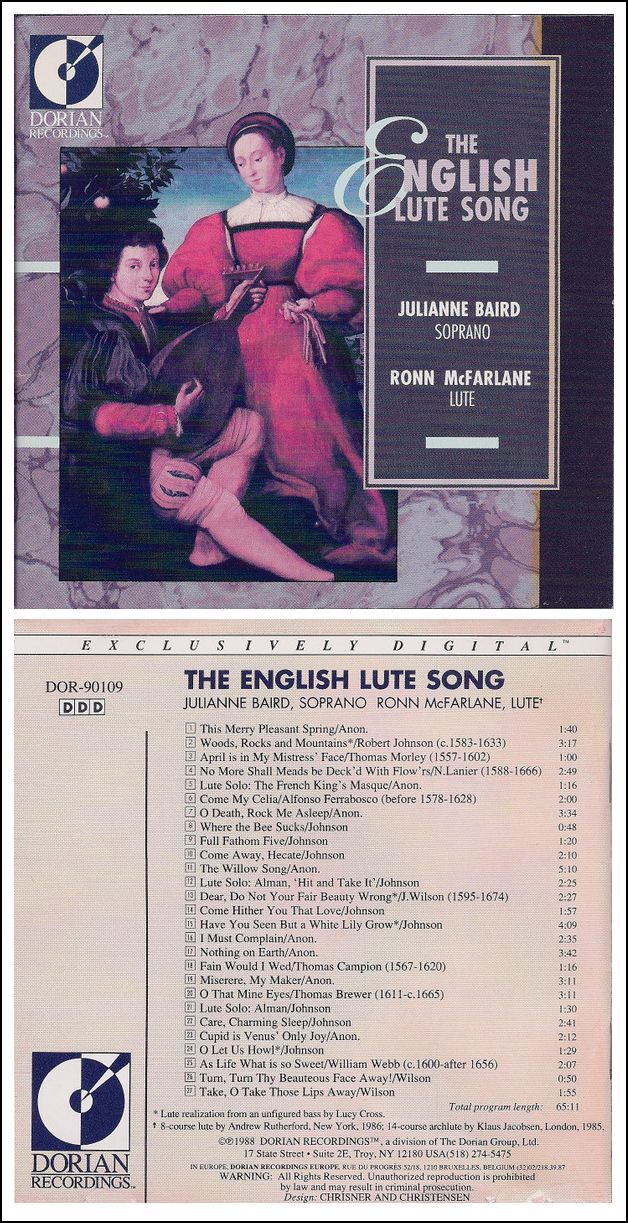

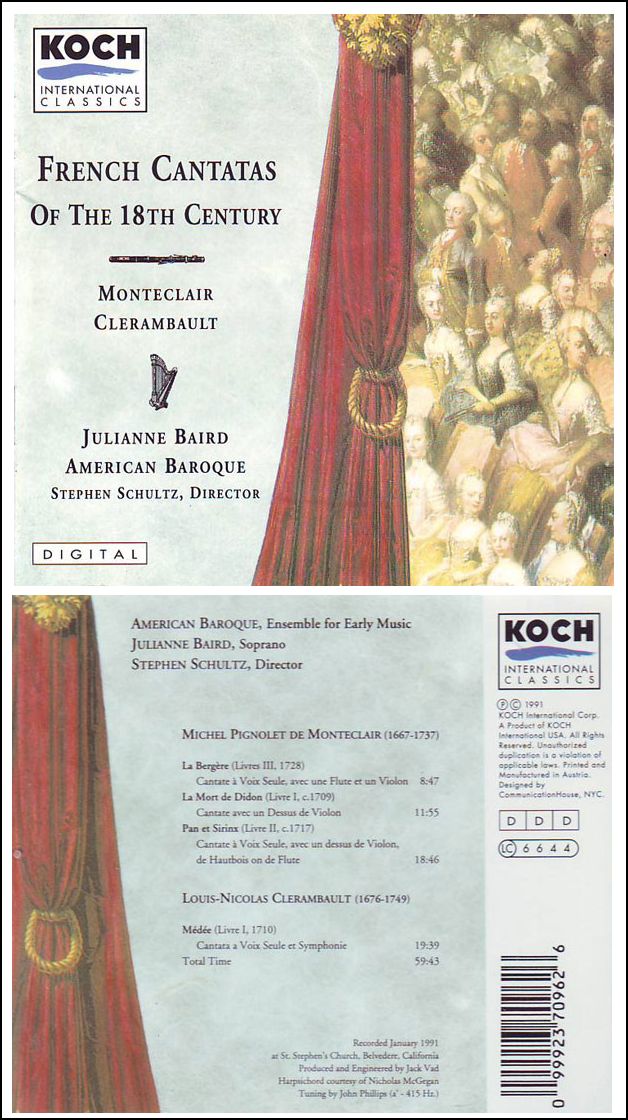

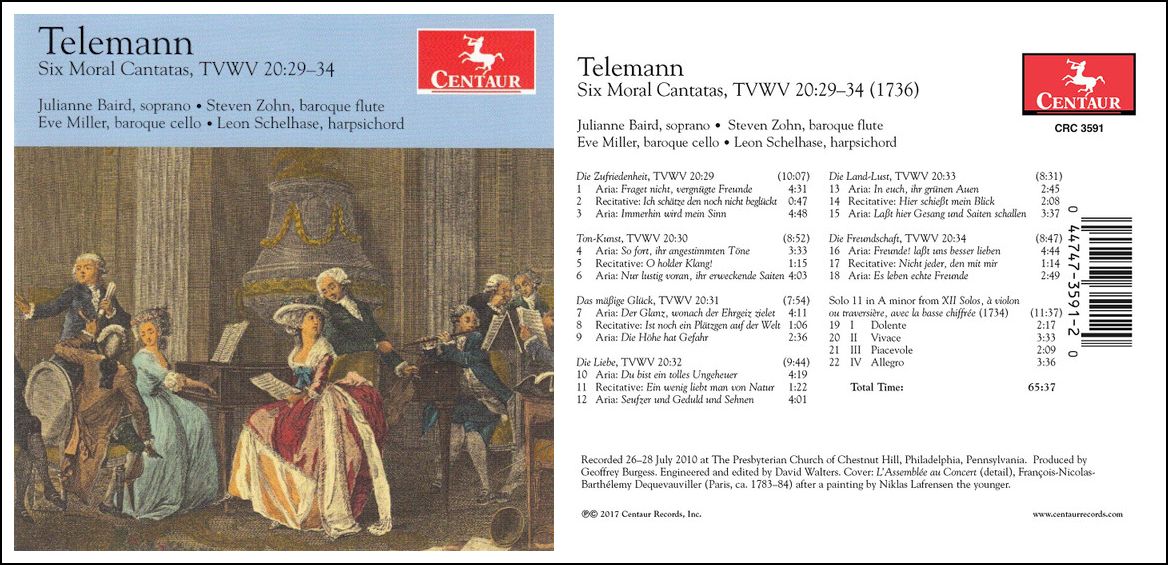

130 solo recordings to her credit on Decca, Deutsche Gramophone, Newport

Classics and Dorian, Julianne Baird is considered one of America's most

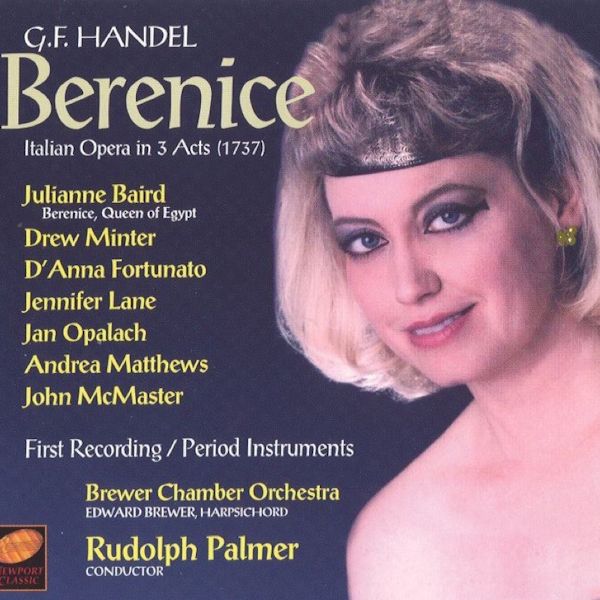

recorded women. In addition to her major roles in the acclaimed series

of Handel operatic and oratorio CD premieres, she has recently sung

leading roles in a series of Gluck Operas CDs. The New York Philharmonic's

box set commemorating it's century of recordings includes her recording

of Reich's "Tehillim."

Other recordings include "Dance on a Moonbeam", featuring Julianne

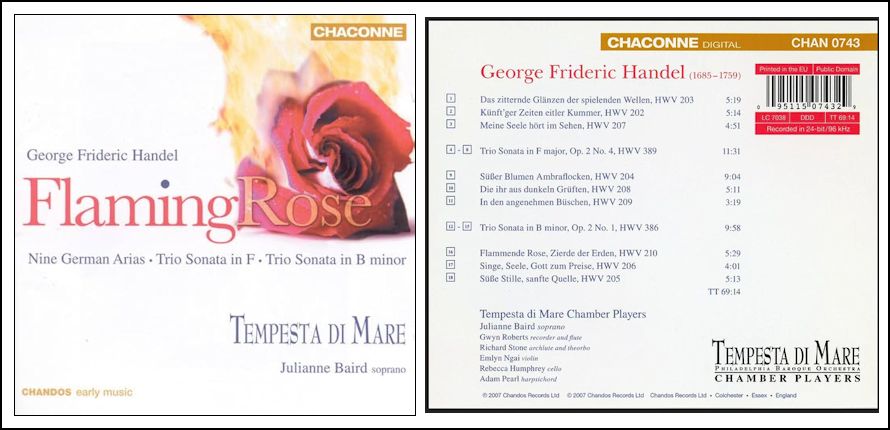

Baird and Meryl Streep. For her recent recording of "Flaming Rose" (Neun

Deutsche Arien) [shown below] the London Sunday Times

had the following: "Baird - a fine American soprano prized for her outstanding

contribution to recordings of Handel operas sings with a delicate timbre

- the singing is exquisitely stylish."

== Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

© 2002 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 24, 2002. Portions were broadcast on WNUR in 2004, and again in 2014. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.