|

Monroe Couper, 40, Composer and Teacher

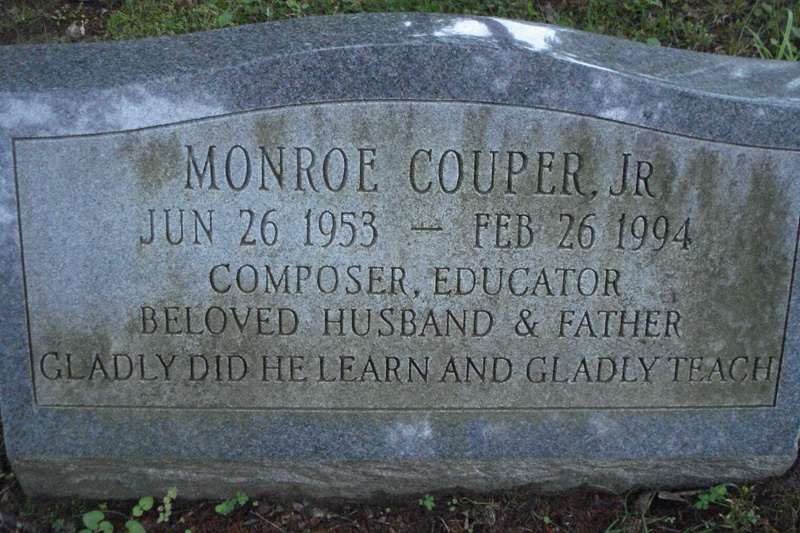

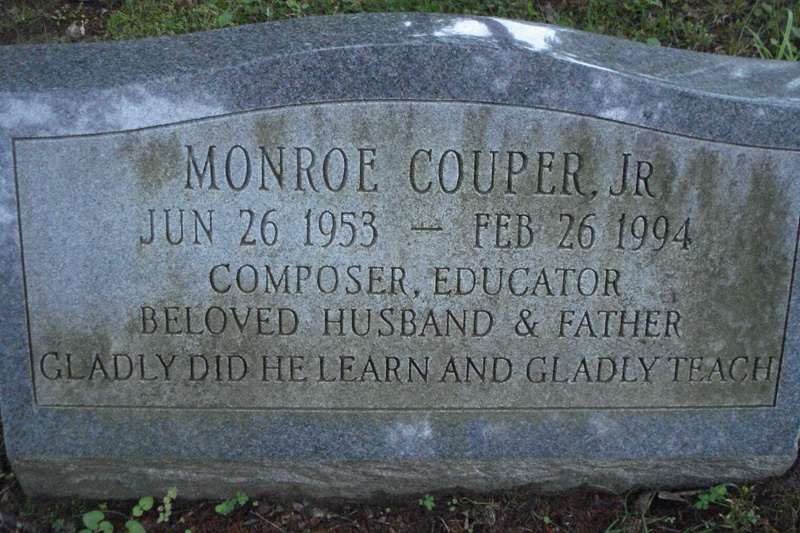

The New York Times, March 5. 1994 Monroe Couper, a composer and an associate professor of music at the Brooklyn College campus of Kingsborough Community College, died last weekend in a climbing accident in New Hampshire. He was 40 and lived in South Orange, N.J. Mr. Couper and Eric Lattey, 28, of River Vale, N.J., froze to death in bad weather while ice-climbing on Mount Washington, the United States Forest Service said. Mr. Couper had been a member of the music faculty at Brooklyn College since 1980. He grew up in Waynesboro, Va., and graduated from the University of Chicago. He taught music theory and electronic music and wrote for orchestras and small ensembles, including percussion quartets. His most recent composition, "In Memoriam," was given its premiere last year by the Prague Symphony Orchestra. He is survived by his wife, Ann Garrison Couper; two daughters, Elisabeth and Mariah; his parents, Charles and Elisabeth Couper of Waynesboro; a brother, and two sisters. |

| National Geographic

Magazine November, 2004 [Portion of the article] No Margin for Error

Despite its modest height—6,288 feet

(1,917 meters)—Mount Washington is America's deadliest peak. And yet the

killing cold and hurricane gusts that scour its summit and load its ravines

with avalanche snow are far from New Hampshire state secrets. So why do otherwise

smart, capable people keep losing their lives up there? By Laurence

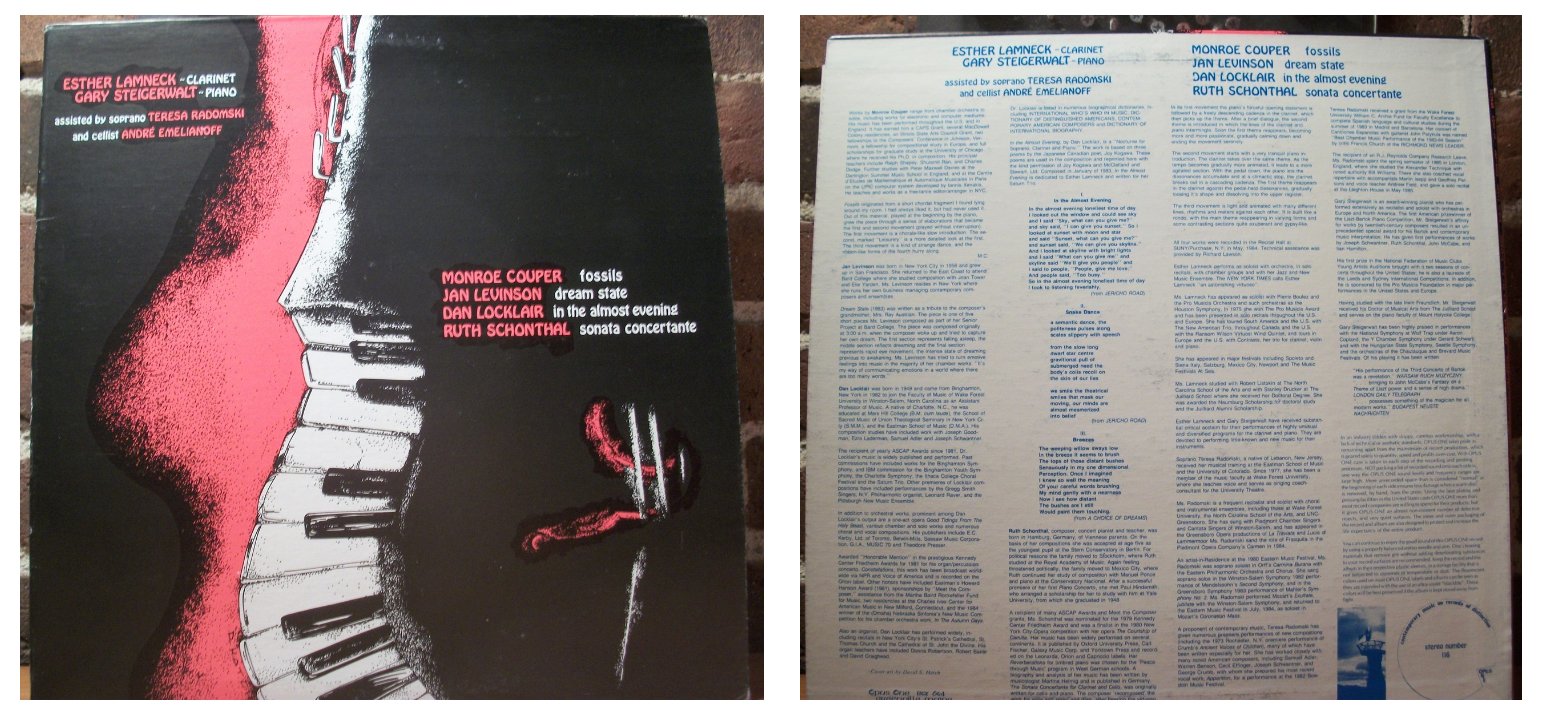

GonzalesWhen Monroe Couper and Erik Lattey left Harvard Cabin on the morning of February 26, 1994, the weather was relatively mild for winter on Mount Washington. The temperature was in the teens and the wind gusts ranged from 40 to 60 miles (64 to 96 kilometers) an hour on the summit. The forecast called for the conditions to hold until nightfall, and since Couper and Lattey didn't plan to go to the summit, they weren't that concerned about it. They intended to hike up Huntington Ravine and climb a wall of frozen groundwater known as Pinnacle Gully. They planned to be back by dark. Traveling light, they left their packs at the cabin.  It's not known for certain, but it's likely that the two ice climbers from

South Orange and Riverdale, New Jersey, had read the recent article in Climbing

magazine about an ascent of Pinnacle Gully, a challenging intermediate climb.

The exciting story of two teenagers who nearly died on a shield of rotten

ice before rescuing themselves had attracted a lot of climbers to the route,

but search and rescue (SAR) volunteers worried that it might encourage people

to push beyond their abilities.

It's not known for certain, but it's likely that the two ice climbers from

South Orange and Riverdale, New Jersey, had read the recent article in Climbing

magazine about an ascent of Pinnacle Gully, a challenging intermediate climb.

The exciting story of two teenagers who nearly died on a shield of rotten

ice before rescuing themselves had attracted a lot of climbers to the route,

but search and rescue (SAR) volunteers worried that it might encourage people

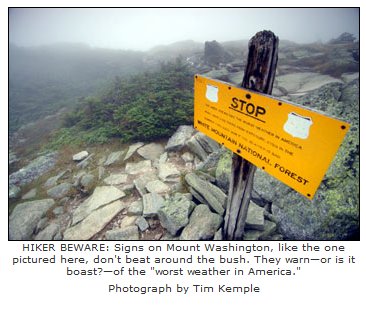

to push beyond their abilities.As Couper and Lattey were hiking up the broad and rugged trail, Alain Comeau, a local guide and team leader for the Mountain Rescue Service (MRS) in New Hampshire, was leading a group up another trail. When he saw fast-moving clouds on the horizon, he turned his group around. Bill Aughton, another member of the MRS, was also out guiding that day. He was so impressed with the clouds that he photographed them before directing his group back toward shelter. Comeau had guided Couper and taught him ice climbing. "Couper wanted to learn to lead," Comeau recalls. "He wanted to move off on his own. A lot of people aspire to a climb like that. But Pinnacle was not the right next step. It's a serious climb in a serious environment. Technically he could have done it—maybe, on a good day in perfect conditions. But on a scale of one to five, Pinnacle's a three-plus." As Couper and Lattey reached the base of the gully, they realized that in their rush they'd forgotten their climbing rope back at Harvard Cabin. It was noon by the time they'd picked up the rope and left the cabin again. Despite their limited experience, they might have easily calculated at this point that they no longer had enough time to make the climb and descend before sunset. (It takes one hour just to get from the cabin to the base of the climb.) They almost certainly could have seen that the weather had started to worsen. And even if they weren't convinced to turn back, they could have read the big yellow signs posted at trailheads. "Stop," they say. Then in smaller letters: "The area ahead has the worst weather in America." Not some of the worst, the worst. The notice continues unequivocally: "Many have died there from exposure, even in the summer. Turn back now if the weather is bad." Couper and Lattey pressed on. The mythology is that anyone can get up Mount Washington, if not to ski its steep ravines, then at least to stand on top and look around. At 6,288 feet (1,917 meters), it may not be high by Rocky Mountain standards, but it ranks as the highest peak in the Presidential Range, and each year scores of people hike the 4,000 vertical feet (1,219 meters) from the trailhead up to the top. (Others drive: An auto road snakes up the northern shoulder of the mountain and is open from May to October.) But a gorgeous day on Mount Washington can turn bitter so fast that most people can't imagine it. They've never seen or felt anything like it, so they don't come armed with the true belief that one gets from direct experience. Like falling into icy water, the sudden cold shocks and numbs and defeats people before they have a chance to think clearly. The first person to climb Washington in winter conditions, in 1849, was also the first person to die there. Since then, 133 more people have lost their lives on the mountain, 24 of them in the past decade. (...) |

This interview was recorded in an office at the University

of Chicago on April 6, 1988. Sections were used (along

with recordings) on WNIB in 1994, and again in 1998. It

was transcribed and posted on this website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.