|

David

Lloyd, Tenor With City Opera, Dies at 92

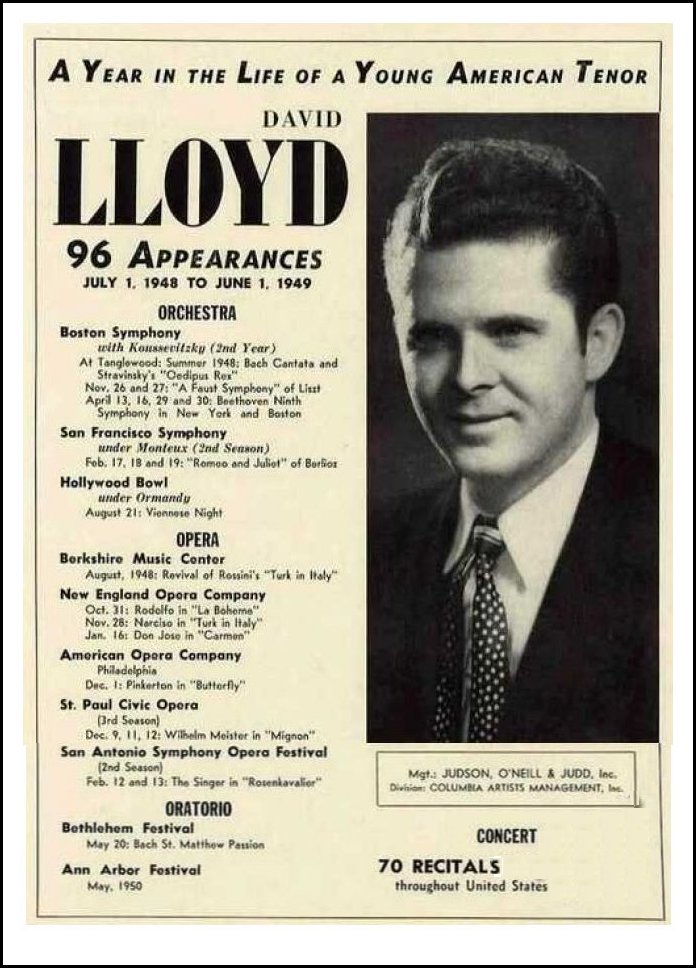

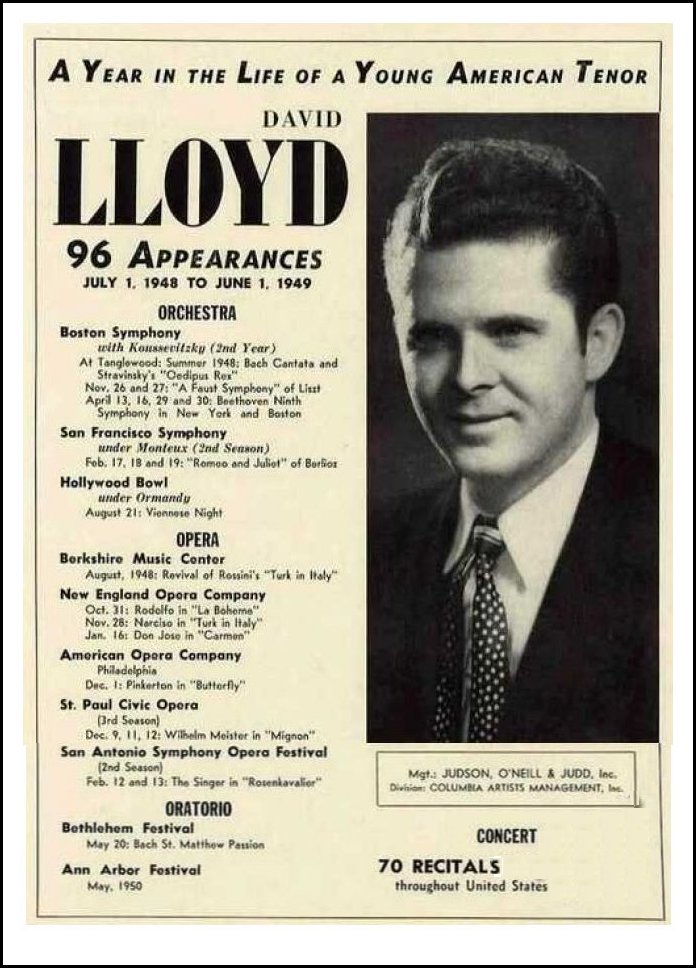

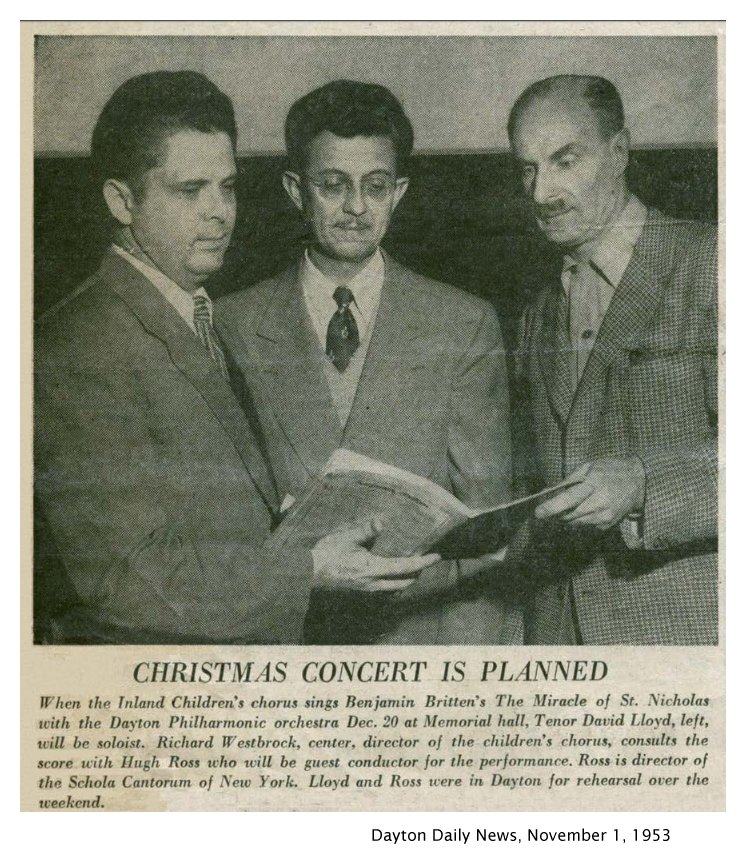

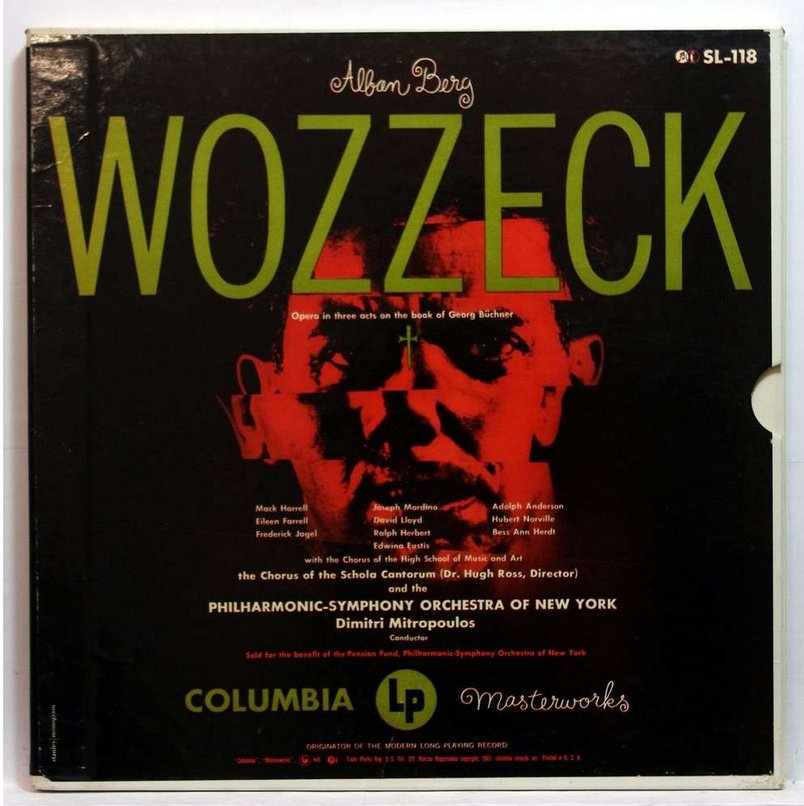

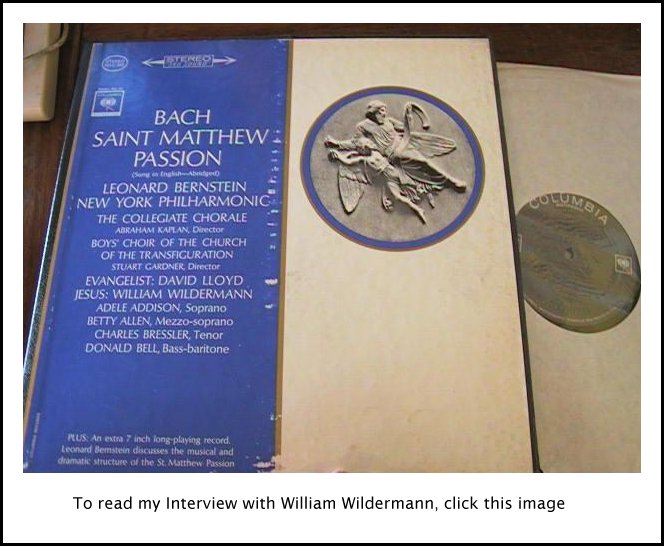

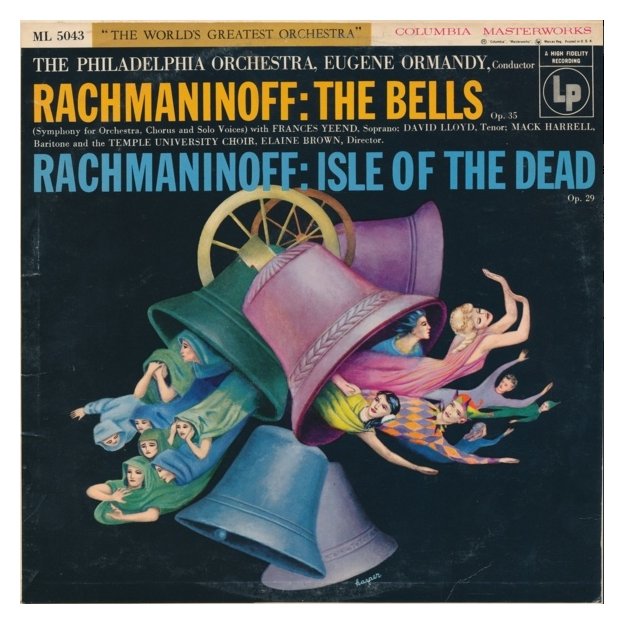

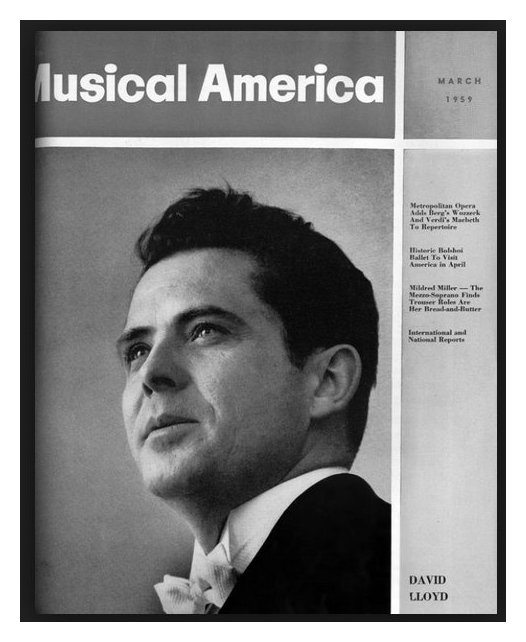

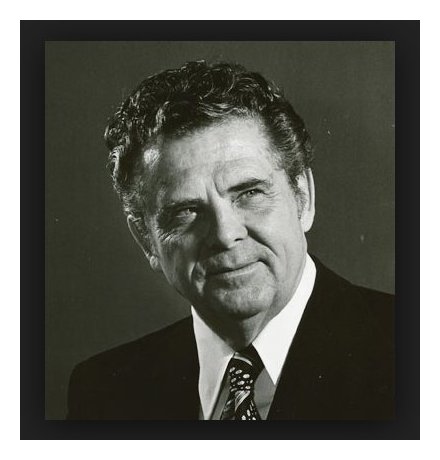

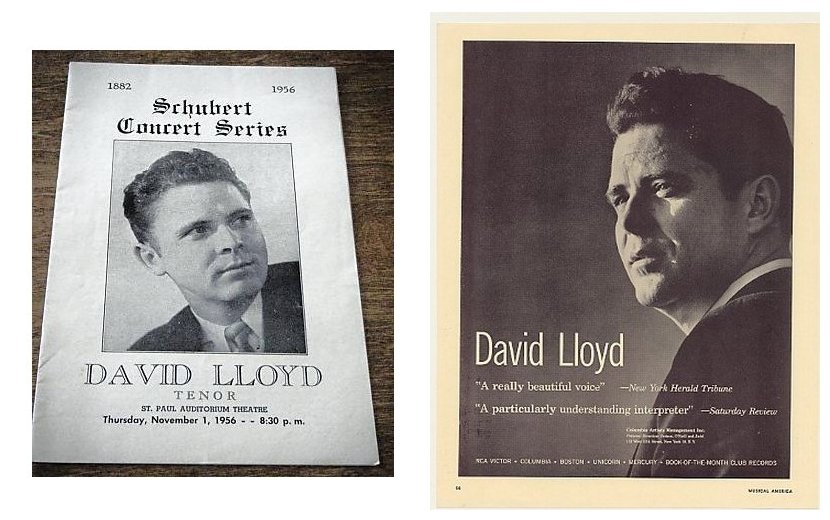

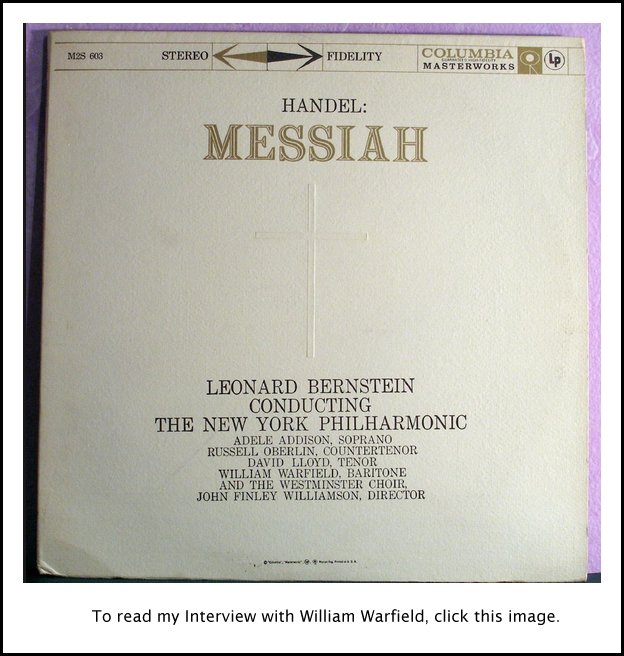

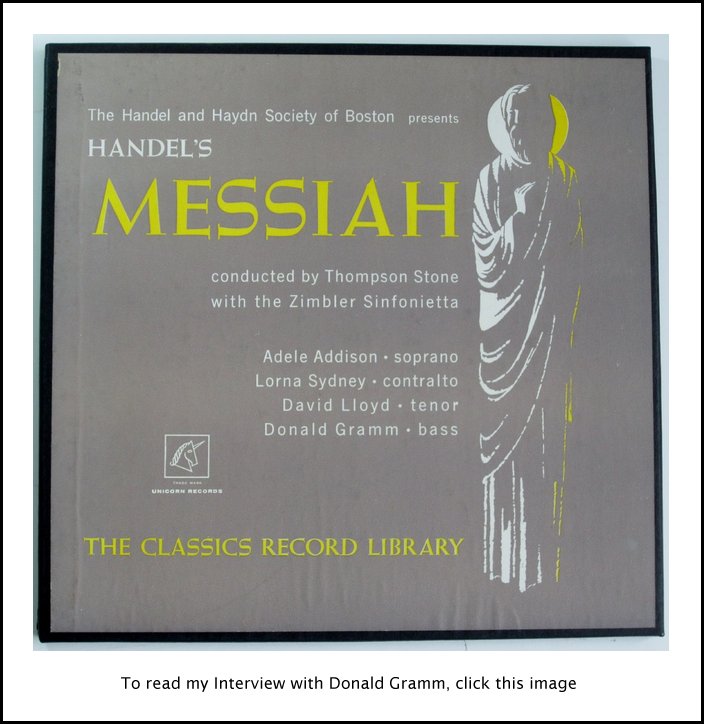

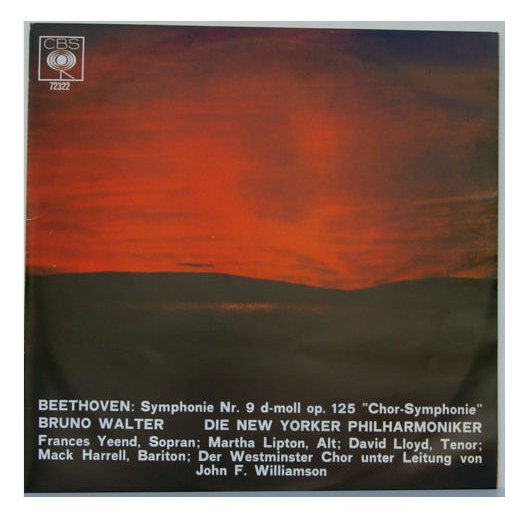

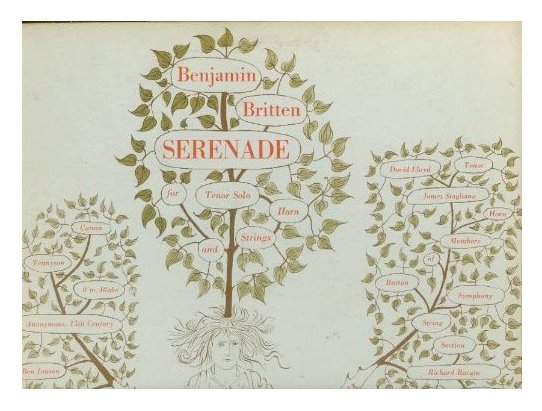

By MARGALIT FOX Published in The New York Times February 12, 2013 David Lloyd, an American tenor who sang leading roles with the New York City Opera in the 1950s, died on Friday in the Bronx. He was 92. His death, at Calvary Hospital, was confirmed by his son, David Thomas Lloyd. A lyric tenor, Mr. Lloyd was equally well known as a recitalist and an oratorio singer. He was praised throughout his career for his insightful musicianship, as in a 1961 recital he gave at Judson Hall in New York of works by Purcell, Brahms, Fauré and Tchaikovsky. Reviewing the recital in The New York Times, Raymond Ericson wrote that Mr. Lloyd’s “contributions to the musical life of New York have been as numerous as they have been splendid.” Mr. Lloyd made his operatic debut with City Opera in 1950, as David in Wagner’s “Meistersinger.” He sang regularly with the company throughout the decade and occasionally thereafter; his roles included Pinkerton in Puccini’s “Madama Butterfly,” the Prince in Rossini’s “Cenerentola,” Alfred in Johann Strauss’s “Fledermaus” and Pedrillo in Mozart’s “Abduction From the Seraglio.” Notable roles elsewhere include the title part in the United States premiere of Benjamin Britten’s comic opera “Albert Herring,” performed at Tanglewood under Boris Goldovsky in 1949. With the NBC Opera Theater, Mr. Lloyd sang in televised productions of Humperdinck’s “Hansel and Gretel,” Prokofiev’s “War and Peace” and other operas in the 1950s. As a soloist, Mr. Lloyd was heard with some of the country’s leading orchestras. His European engagements included the Glyndebourne and Edinburgh Festivals. David Lloyd Jenkins was born in Minneapolis on Feb. 29, 1920. (He dropped the “Jenkins” early in his career, at the suggestion of his management.) He earned a bachelor’s degree from the Minneapolis College of Music and later attended the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where he studied with the Metropolitan Opera baritone Richard Bonelli. During World War II, Mr. Lloyd served as a Navy pilot. Mr. Lloyd had a second career as an arts administrator and teacher. From 1965 until 1980 he was the general director of the Lake George Opera Festival in upstate New York. (The festival is now known as Opera Saratoga.) From 1985 to 1988 he directed the Juilliard American Opera Center. Mr. Lloyd’s first wife, the former Maria Shefeluk, a violinist, died before him, as did a son, Timothy Cameron Lloyd, a composer. Besides his son, David Thomas, he is survived by his second wife, Barbara Wilson Lloyd, and a grandson. His recordings include Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion” and Handel’s “Messiah,” both with the New York Philharmonic under Leonard Bernstein, and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, with the Boston Symphony under Serge Koussevitzky.

|

DL:

Fachs were invented by German impresarios

because in the smaller houses, if they got twelve singers, one of each Fach, they can do almost any opera.

We didn’t have enough opera companies here in the U.S., or enough opera going

on when I was doing most of my singing to be choosey. Somebody said

to me, “You should do nothing but David,” because I’d had a success with

David in Meistersinger at the City

Opera. After my debut in 1950 he said, “You should do nothing but David

and Pedrillo in the Abduction from the

Seraglio. Just do those two roles.” Well, in this country

I would have starved to death because nobody was doing either one of those

very much. Meistersinger was

a rare item in those days. I was invited to do it at the Met, but my

manager wouldn’t let me do it because they wouldn’t give me the first performance,

so they turned it down. At that time my manager, Arthur Judson, was

warring heavily with Rudolph Bing, who was new.

DL:

Fachs were invented by German impresarios

because in the smaller houses, if they got twelve singers, one of each Fach, they can do almost any opera.

We didn’t have enough opera companies here in the U.S., or enough opera going

on when I was doing most of my singing to be choosey. Somebody said

to me, “You should do nothing but David,” because I’d had a success with

David in Meistersinger at the City

Opera. After my debut in 1950 he said, “You should do nothing but David

and Pedrillo in the Abduction from the

Seraglio. Just do those two roles.” Well, in this country

I would have starved to death because nobody was doing either one of those

very much. Meistersinger was

a rare item in those days. I was invited to do it at the Met, but my

manager wouldn’t let me do it because they wouldn’t give me the first performance,

so they turned it down. At that time my manager, Arthur Judson, was

warring heavily with Rudolph Bing, who was new. DL: The research is very important, just so it doesn’t

interfere with your singing. It gives color to the singing. I

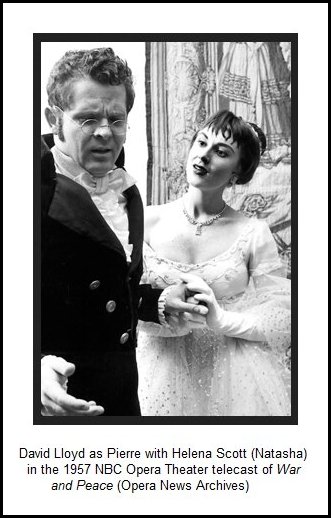

remember when I did the part of Pierre in War and Peace of Prokofiev. [The role had been sung by Franco Corelli at

the Italian premiere on May 26, 1953, in Florence.] That was

a newer work then, and it was the premiere of that opera in this country

on NBC Television [January 13, 1957]. I read the Tolstoy novel, and

then I went through it again and underlined everything that was in the opera.

I had such a feeling for that character that I could think his thoughts in

case somebody wrote more music for the part! I felt very happy about

that role, and I saw our performance of it recently at the Museum of Television.

It came out pretty well.

DL: The research is very important, just so it doesn’t

interfere with your singing. It gives color to the singing. I

remember when I did the part of Pierre in War and Peace of Prokofiev. [The role had been sung by Franco Corelli at

the Italian premiere on May 26, 1953, in Florence.] That was

a newer work then, and it was the premiere of that opera in this country

on NBC Television [January 13, 1957]. I read the Tolstoy novel, and

then I went through it again and underlined everything that was in the opera.

I had such a feeling for that character that I could think his thoughts in

case somebody wrote more music for the part! I felt very happy about

that role, and I saw our performance of it recently at the Museum of Television.

It came out pretty well. BD:

That’s loud and heavy, but short.

BD:

That’s loud and heavy, but short. DL:

I think favorably, certainly potentially. We didn’t hear Caruso today

nor did we hear Ponselle, but we heard some people that with the right care

and feeding can probably go very far in that direction. There is an

enormous amount of singing talent. Certainly, there’s an awful lot

more people today trying to be singers, and in order to be a singer today

you can’t do what I did and go out on community concerts. I sang 75

one year. There aren’t that many concerts to be sung, and not many

people want to hear full recitals anymore. Oratorios are still going

on, but there seemed to be a lot more when I was singing. In my time

I sang about 70 times with the Boston Symphony, doing orchestral things for

voices including Bach cantatas in their Bach-Mozart Series at Tanglewood.

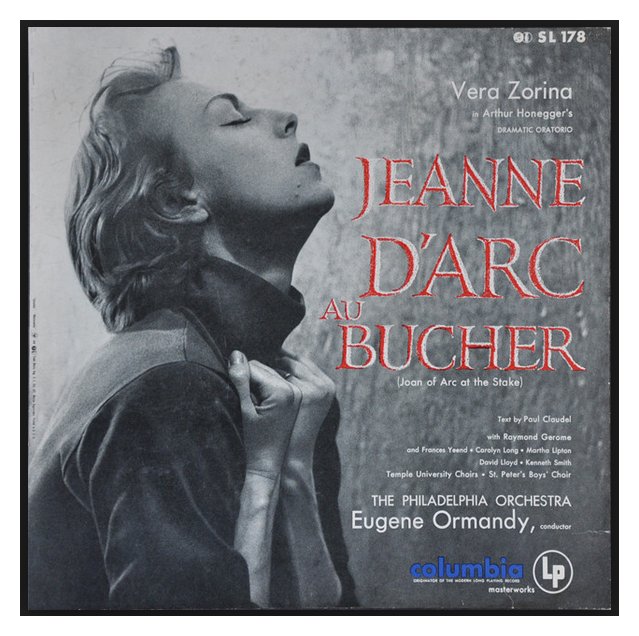

I also sang about 50 times with the Philadelphia Orchestra, and about the

same number of times with the New York Philharmonic because there were so

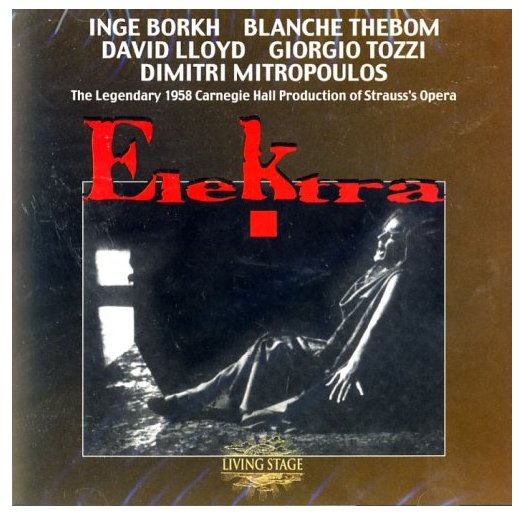

many things for singers to do. Mitropoulos got there and did a lot of

operas. I did a lot of concert versions with him.

DL:

I think favorably, certainly potentially. We didn’t hear Caruso today

nor did we hear Ponselle, but we heard some people that with the right care

and feeding can probably go very far in that direction. There is an

enormous amount of singing talent. Certainly, there’s an awful lot

more people today trying to be singers, and in order to be a singer today

you can’t do what I did and go out on community concerts. I sang 75

one year. There aren’t that many concerts to be sung, and not many

people want to hear full recitals anymore. Oratorios are still going

on, but there seemed to be a lot more when I was singing. In my time

I sang about 70 times with the Boston Symphony, doing orchestral things for

voices including Bach cantatas in their Bach-Mozart Series at Tanglewood.

I also sang about 50 times with the Philadelphia Orchestra, and about the

same number of times with the New York Philharmonic because there were so

many things for singers to do. Mitropoulos got there and did a lot of

operas. I did a lot of concert versions with him. BD:

Are there any roles that you wish you had gotten the opportunity to learn

and sing a few times?

BD:

Are there any roles that you wish you had gotten the opportunity to learn

and sing a few times?

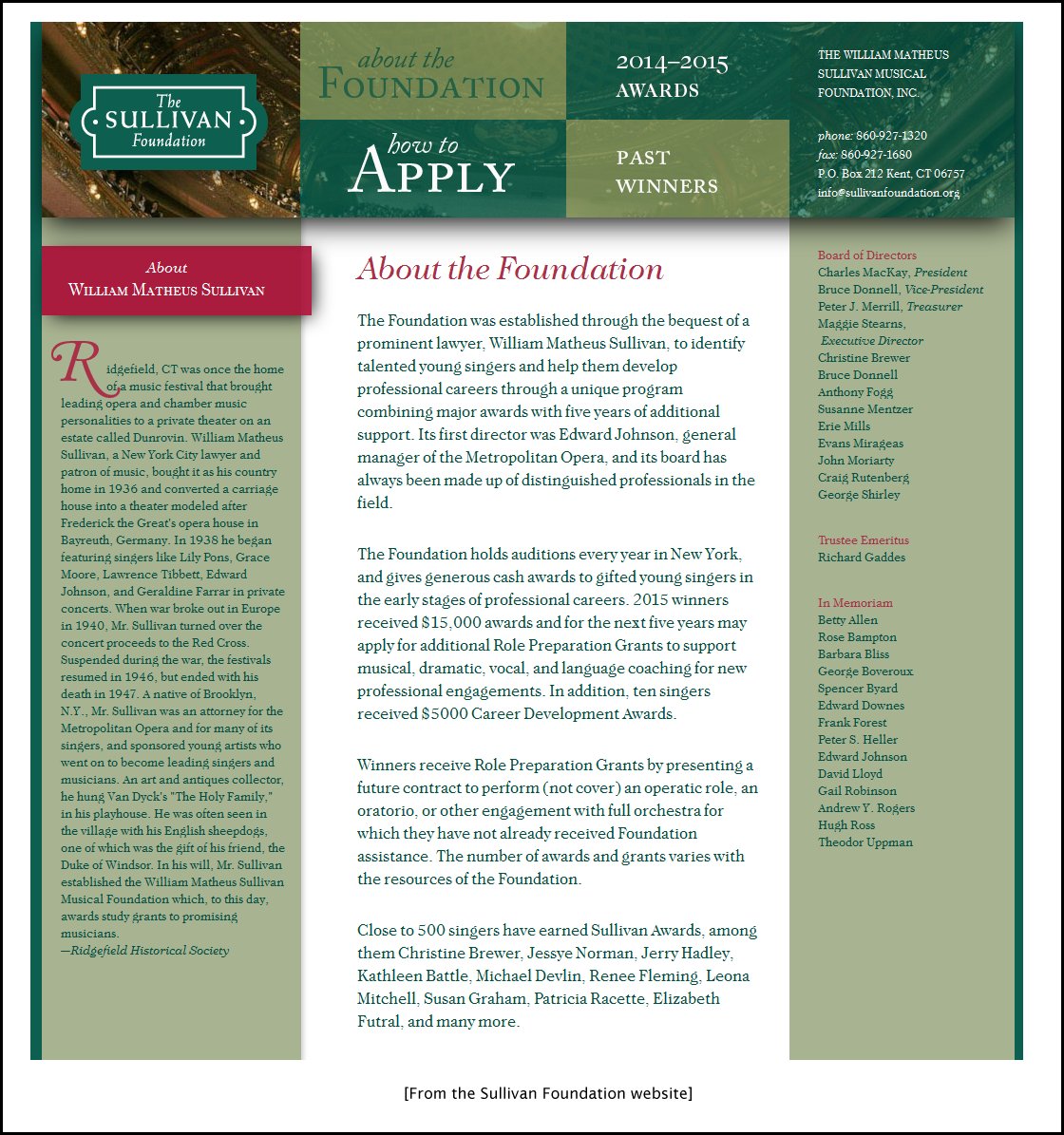

See my interviews with Jerry Hadley, Renée Fleming, Susan Graham, Patricia Racette, Susanne Mentzer, George Shirley, Rose Bampton, Edward Downes, and Theodor Uppman |

DL:

When it works, there’s nothing better. It is a wonderful experience!

All the nerve endings light up when you see a singer who is singing well.

They become much better looking than when they’re in repose. They glow.

They really do, and even if they may be a little bit on the ugly side as

just ordinary people, when they’re singing well they become beautiful to

look at as well as listen to. It’s strange. I’ve noticed that.

DL:

When it works, there’s nothing better. It is a wonderful experience!

All the nerve endings light up when you see a singer who is singing well.

They become much better looking than when they’re in repose. They glow.

They really do, and even if they may be a little bit on the ugly side as

just ordinary people, when they’re singing well they become beautiful to

look at as well as listen to. It’s strange. I’ve noticed that. BD: It’s great that you’re sharing your knowledge

and enthusiasm.

BD: It’s great that you’re sharing your knowledge

and enthusiasm.

|

|

|

|

|

|

See my interview with Martha Lipton

|

© 1991 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 15, 1991.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1995 and 2000. This transcription

was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.