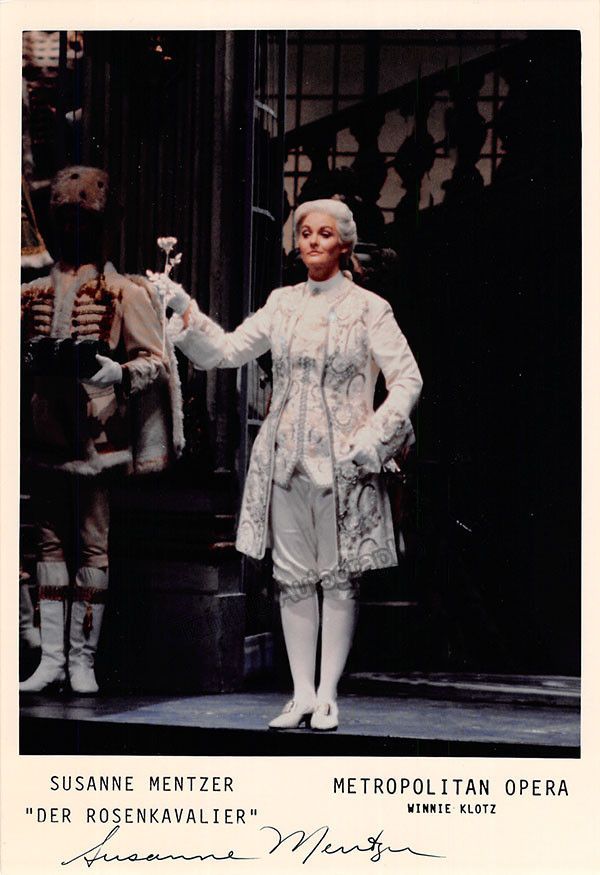

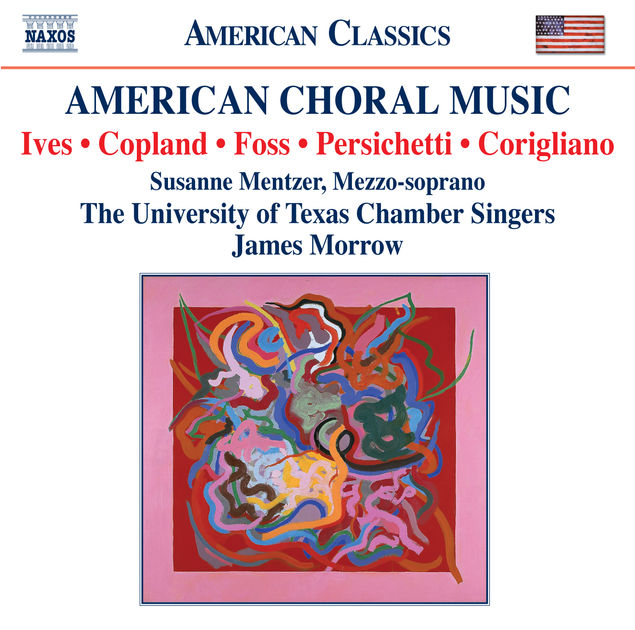

American mezzo-soprano Susanne Mentzer

is an international opera star, known for a strong, bright stage presence

and agile lyric voice that has made her a natural for the leading travesti

(trousers) roles. She is also active as a concert and recital singer. Raised in her home town of Philadelphia, she moved to Santa

Fe, NM, and finished her last two years of high school there. This

led to ushering at the Santa Fe Opera Festival, which awakened an interest

in classical singing.

Raised in her home town of Philadelphia, she moved to Santa

Fe, NM, and finished her last two years of high school there. This

led to ushering at the Santa Fe Opera Festival, which awakened an interest

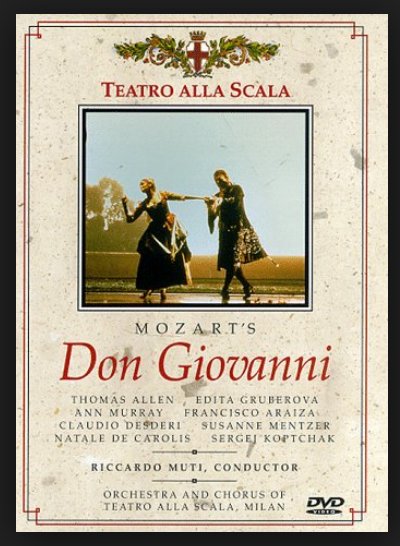

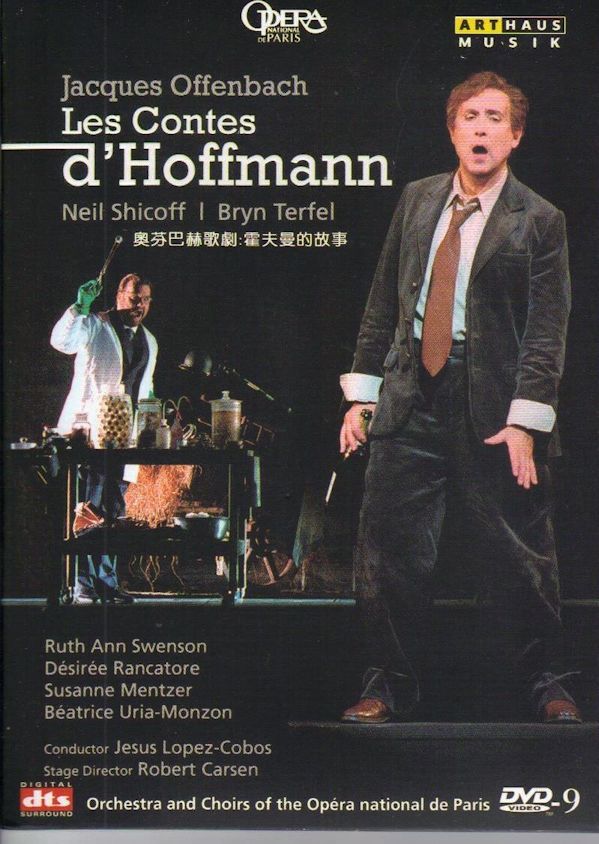

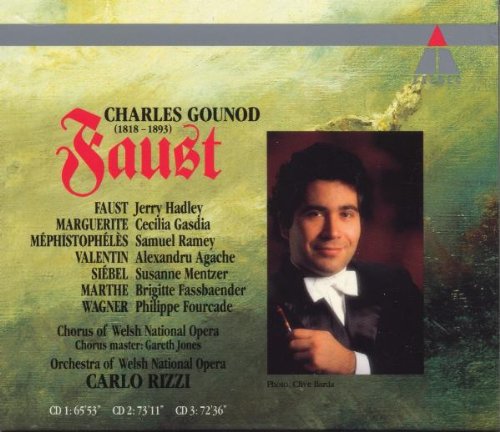

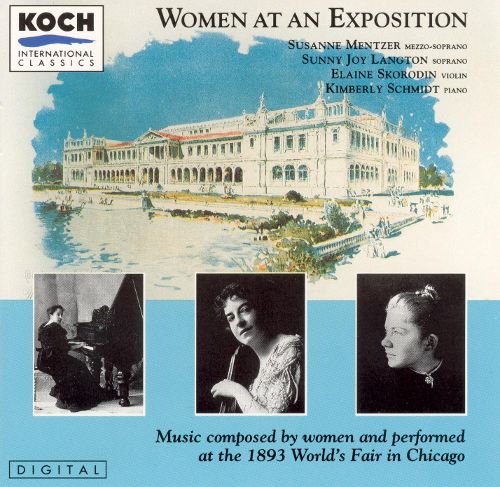

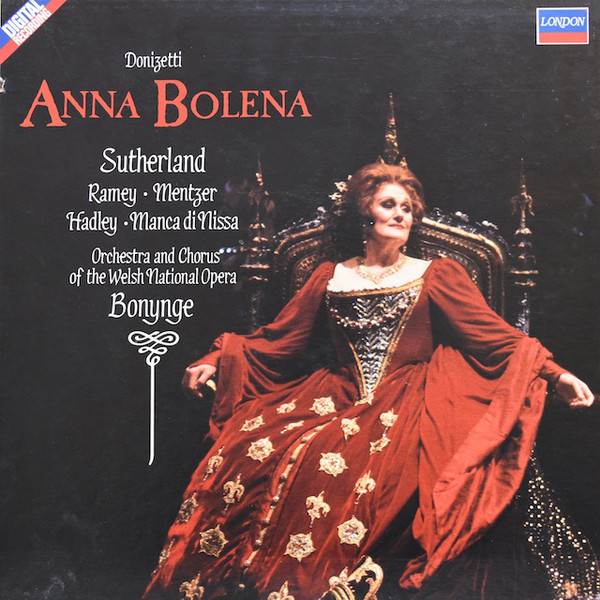

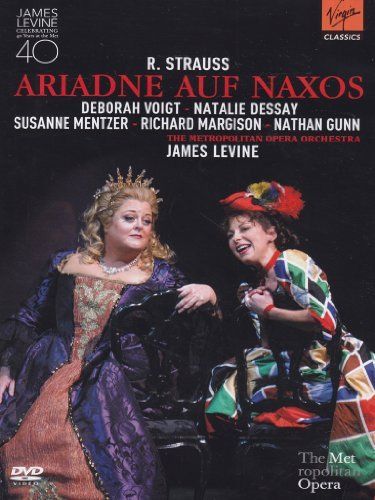

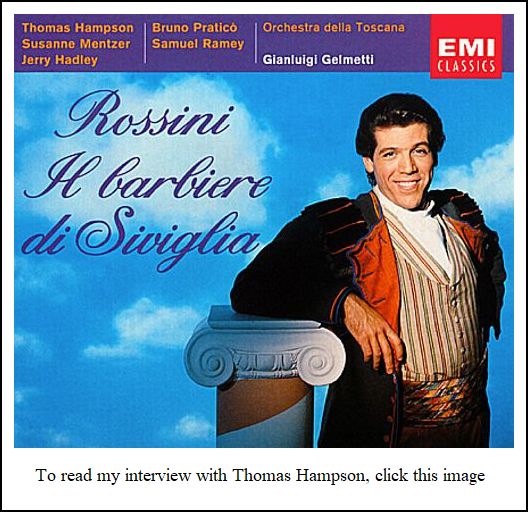

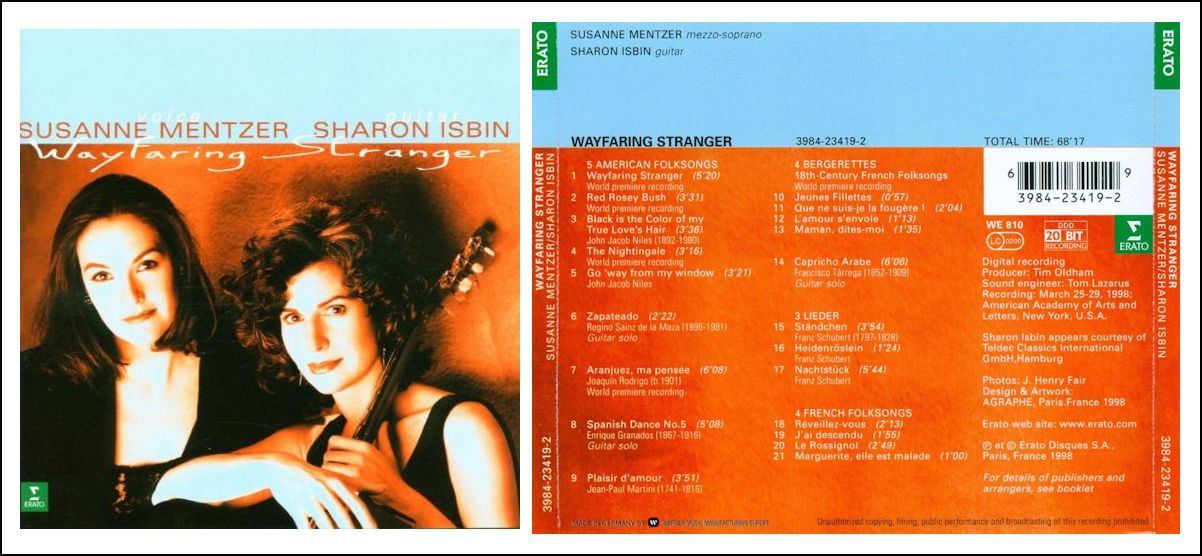

in classical singing.She enrolled in the University of the Pacific in Stockton, CA, as a music therapy major. Her music teachers immediately spotted her vocal potential and her flair for the stage, and sent her as an apprentice at the Aspen Music Festival after her first college year. Despite her rookie status, she beat all the rest of the competition for the trousers role of Nicklausse in Offenbach's Les Contes d'Hoffmann, which, she says, got her "really hooked on opera." She transferred to the Juilliard School of Music in New York City, where she studied with Norma Newton. Her professional stage debut was as Albina in Rossini's La donna del lago with the Houston Grand Opera in 1981. She made an acclaimed European debut in 1983 at Cologne as Cherubino in Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro. She rapidly established a strong European reputation, singing Rosina in The Barber of Seville at Covent Garden in 1985. Despite her growing fame in trousers parts (Octavian in Strauss' Der Rosenkavalier, Cherubino, Idamante, Sextus, the Composer in Ariadne auf Naxos, and others), she also enchanted audiences as Dorabella in Così fan tutte and in the soubrette part of Zerlina in Don Giovanni, which she sang in 1987 at La Scala in Milan under the baton of Ricardo Muti -- a portrayal available on video [shown at right. See my interviews with Thomas Allen, Ann Murray, and Francisco Araiza. Mentzer also appears on an audio recording on EMI, made in Vienna with Muti and a different cast.] In 1987, as she was starting a family, she returned to the United States as a residence and base of operations. She made her Metropolitan Opera debut as Cherubino in 1989. When she started rehearsals, she recalls, her son Benjamin was four months old and still being breast-fed, so she was "feeling not very man-like." She has developed into a natural successor to Marilyn Horne in the great coloratura mezzo roles of the bel canto era, such as Adalgisa in Bellini's Norma, and the growing interest in Baroque opera led to great acclaim in the title role of Handel's Giulio Cesare at the Bastille Opéra in Paris, where she has also sung Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande. Among her other roles are Romeo in I Capuleti e i Montecchi, Giovanna Seymour in Anna Bolena, Marguerite in La damnation de Faust, the title roles of Offenbach's La Périchole and Ravel's L'Enfant et les sortileges, Rossini's Cenerentola, and Purcell's Dido and Aeneas, and Concepcion in Ravel's L'heure espagnole. In concert, she has sung in major works of Bach, Beethoven, Debussy, Falla, Mahler, Handel, Stravinsky, Ravel, Mozart, Floyd, Bruckner, Berlioz, Berg, and Pergolesi. Her growing number of recital programs tend to feature innovative mixes of art songs, operatic arias, and American folk songs, with an interest in vocal music by women composers. Mentzer has recorded for Philips, Telarc, Virgin, Decca, Erato, Arabesque, and Angel/EMI. She frequently sings in benefits for charities related to the care of AIDS patients, including an annual "Jubilate" concert in Chicago. |

BD: Do you feel that Massenet wrote

well for the voice?

BD: Do you feel that Massenet wrote

well for the voice?  BD: Being involved in the opera, does

he understand your problems a bit more, and can he sympathize with

your need to travel so much?

BD: Being involved in the opera, does

he understand your problems a bit more, and can he sympathize with

your need to travel so much?  BD: Do you rely on the prompter at all?

BD: Do you rely on the prompter at all?

Susanne Mentzer at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1984 - Barber of Seville (Rosina) with Raftery, Araiza, Siepi,

Montarsolo,

Andreolli;

Bartoletti,

Sciutti,

Schuler

1986-87 - Merry Widow (Valencienne) with Ewing, Titus, Hadley, Adams, Kaasch, Negrini; Podič, Mansouri, Tallchief 1989-90 - Clemenza di Tito (Sesto) with Winbergh, Vaness, Graham, Doss; Davis, Rochaix 1991-92 - Marriage of Figaro (Cherubino) with Lott, Ramey, McLaughlin, Shimell, Loup, Benelli, Palmer, Futral (Barbarina); Davis, Hall 1993-94 - Don Quichotte (Dulcinée) with Ramey, Lafont, Perkins; Nelson, Koenig, Samaritani 1994-95 - Barber of Seville (Rosina) with Braun/Gilfrey, Blake, Halfvarson, Desderi; Behr, Copley, Conklin 1995-96 - Don Giovanni (Zerlina) with Morris, Terfel/Held, Orgonasova, Vaness, Lopardo; Kreizberg, Ponnelle

To launch the Chicago Symphony Orchestra's 100th season, an all-star cast of conductors and soloists was assembled for a gala opening concert on October 6, 1990. Left to right, back row: Associate Conductor Kenneth Jean, pianist András Schiff, conductor Lorin Maazel, tenor Gary Lakes, soprano Sylvia McNair, bass Samuel Ramey; middle row: Music Director Designate Daniel Barenboim, Lady Valerie Solti, Music Director Sir Georg Solti, conductor Leonard Slatkin, cellist Yo-Yo Ma; front row: violinist Isaac Stern, cellist/conductor Mstislav Rostropovich, mezzo-soprano Susanne Mentzer, pianist/conductor Murray Perahia. |

BD: Is singing fun?

BD: Is singing fun? With that I wished her well and hoped for continued success. We agreed to meet again in the future, which we did twelve years later, at the beginning of the final year of the 1900s. Her career was moving along nicely, and it was good to see the growth in her artistry, and understanding of all that goes with it.

BD: But the German and the French songs do?

BD: But the German and the French songs do?  BD: Can you ask the conductor to hold them back?

BD: Can you ask the conductor to hold them back? BD: You’re on stage most of the night.

BD: You’re on stage most of the night. BD: But you do some leading roles

— Rosina in Barber of Seville, and Cenerentola.

BD: But you do some leading roles

— Rosina in Barber of Seville, and Cenerentola.  SM: That’s a toughie. There’s a lot of different

ways of looking at it. I don’t think it’s a happy ending.

I don’t think anybody ends up with anybody. If you’ve had

an affair, life will never be the same with that person again.

I think everybody splits up and goes on with their life, but Mozart didn’t

write that. He didn’t write a sequel, so we don’t know.

SM: That’s a toughie. There’s a lot of different

ways of looking at it. I don’t think it’s a happy ending.

I don’t think anybody ends up with anybody. If you’ve had

an affair, life will never be the same with that person again.

I think everybody splits up and goes on with their life, but Mozart didn’t

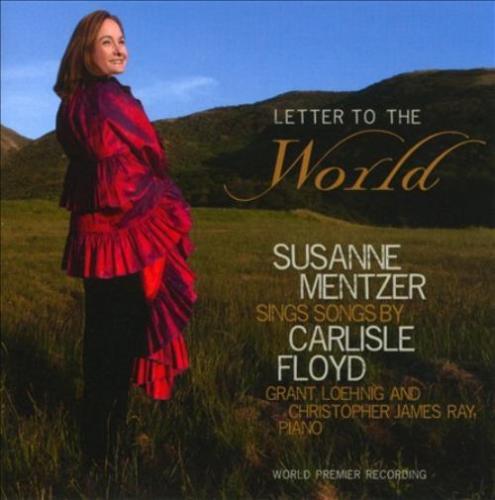

write that. He didn’t write a sequel, so we don’t know. SM: Right. And I’ve been nagging Carlisle Floyd

to write an opera for me, but he hasn’t done it. He likes

sopranos. I did a song cycle of his, a world premiere of an Emily

Dickinson cycle, and I just love his music.

SM: Right. And I’ve been nagging Carlisle Floyd

to write an opera for me, but he hasn’t done it. He likes

sopranos. I did a song cycle of his, a world premiere of an Emily

Dickinson cycle, and I just love his music.  SM: [With a contented look] It’s emotional expression.

So, when a person listens to music, it stirs emotions in them.

A person who performs music, it also stirs emotions. I can only

speak from being a singer, because I’m not a great pianist or instrumentalist,

but I really don’t know anybody who sings for the technical aspects of

it. They sing because they have something to say, and we didn’t

get into singing because we’re going to make money. You go into

singing because you had something to say, and you have this need to express.

I don’t think a writer goes into writing, or a poet goes to write poetry

just to make a living. You start doing it because it’s something

emotional. It’s good to go back to your first amateur experiences.

That’s something that’s lacking in America. In the middle of the

century and before, there were so many amateur organizations. Every

little town had their orchestra and their band and a chorus, or a choral

society. Fortunately, in Chicago we have a great choral tradition,

but most of America doesn’t. So, they don’t have that exposure, and

it’s all based on money. Most people don’t go into music for money,

but there are few people who just do it just for fun, and that’s sad.

SM: [With a contented look] It’s emotional expression.

So, when a person listens to music, it stirs emotions in them.

A person who performs music, it also stirs emotions. I can only

speak from being a singer, because I’m not a great pianist or instrumentalist,

but I really don’t know anybody who sings for the technical aspects of

it. They sing because they have something to say, and we didn’t

get into singing because we’re going to make money. You go into

singing because you had something to say, and you have this need to express.

I don’t think a writer goes into writing, or a poet goes to write poetry

just to make a living. You start doing it because it’s something

emotional. It’s good to go back to your first amateur experiences.

That’s something that’s lacking in America. In the middle of the

century and before, there were so many amateur organizations. Every

little town had their orchestra and their band and a chorus, or a choral

society. Fortunately, in Chicago we have a great choral tradition,

but most of America doesn’t. So, they don’t have that exposure, and

it’s all based on money. Most people don’t go into music for money,

but there are few people who just do it just for fun, and that’s sad.

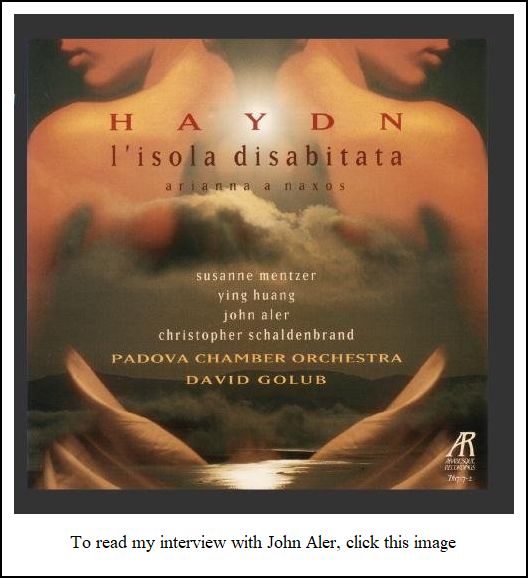

BD: Tell me about the Haydn opera you’ve just recorded.

BD: Tell me about the Haydn opera you’ve just recorded.

© 1987 & 1999 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on January 5,1987, and January 30, 1999. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1989, and again in 1993, 1997, and 1999. Much of the first interview was transcribed and published in the Massenet Newsletter in January, 1988. It was slightly re-edited for this website presentation. The transcript of the second interview was made in 2017, and both were posted on this website early in 2018. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.