A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

BD: You’re his Köchel?

BD: You’re his Köchel? BD: You’re going to get the brass players and

the tuba players and interested composers and a few managers, but that’s

why I’m interested in the general public coming.

BD: You’re going to get the brass players and

the tuba players and interested composers and a few managers, but that’s

why I’m interested in the general public coming. BD: There were enough tuba players to do that?

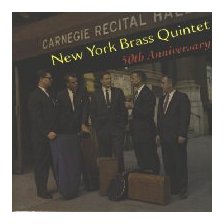

BD: There were enough tuba players to do that? HP: Oh, yes! The first album we did was

called New York Brass Quintet in Concert.

It has the Eugene Bozza piece and several other great works on it.

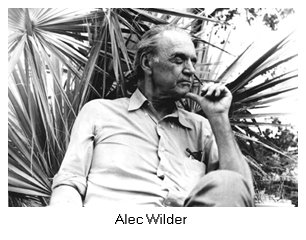

Then we did Alec’s First Suite for Brass

Quintet, and on the other side is a suite by Donald Hammond, which

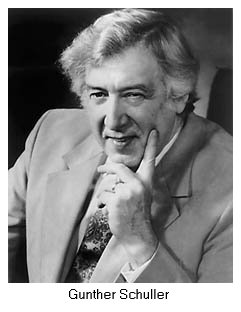

is quite a nice piece. Then we recorded Gunther’s piece for CRI and

a Harold Farberman piece. Quite a number of works we recorded for CRI.

Then we had a contract with RCA. I was a very close friend of Howard

Scott who negotiated that contract for us. We were supposed to do six

albums, but shortly after we did the first album I left the Quintet, and

RCA cancelled the contract. So the New York Brass Quintet only did

one RCA album.

HP: Oh, yes! The first album we did was

called New York Brass Quintet in Concert.

It has the Eugene Bozza piece and several other great works on it.

Then we did Alec’s First Suite for Brass

Quintet, and on the other side is a suite by Donald Hammond, which

is quite a nice piece. Then we recorded Gunther’s piece for CRI and

a Harold Farberman piece. Quite a number of works we recorded for CRI.

Then we had a contract with RCA. I was a very close friend of Howard

Scott who negotiated that contract for us. We were supposed to do six

albums, but shortly after we did the first album I left the Quintet, and

RCA cancelled the contract. So the New York Brass Quintet only did

one RCA album. BD: In the end, obviously, it didn’t break your

health. Was it worth it?

BD: In the end, obviously, it didn’t break your

health. Was it worth it? BD: Are you optimistic about the future of music?

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of music? HP: No, I don’t think so. Think, for example,

of the violin. They are very fortunate to have had great artists such

as Guarneri and Stradivarius who created the ultimate, the nearest thing

to perfect instrument of that kind that could be created. It took our

brass instruments a lot longer because we didn’t even have the valve until

1819. And valves didn’t find their way to the tuba and the other instruments

— so they could be chromatic — until the

middle 1830’s. That’s why we missed out on Beethoven and Bach.

Shortly after I arrived at the Julliard School, I had a practice room assigned

to me for the evening. On my way I passed studios where pianists were

playing Tchaikovsky and violinists were practicing Mendelssohn and Tchaikovsky

and flute players were playing the Handel Flute Sonatas, and horn player was playing

the Mozart Tuba Concertos.

Old Mozart was clairvoyant; he knew some day there’d be tubas, so he wrote

four concertos! [Both laugh uproariously] Then I get to my studio,

take off my coat, take my tuba out of its cover, and put music on the stand

and start going through it. I’ve got Solo Pomposo, Bombasto, Hall of the Mountain King, Down in the Deep Cellar and all this

trite music. I put it back in the briefcase and left. The next

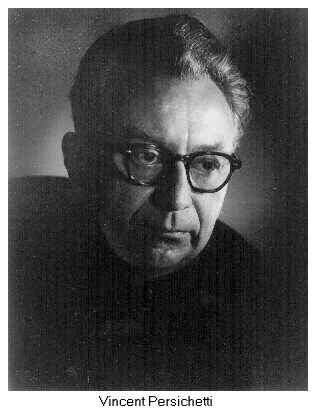

morning I had a class with Vincent Persichetti.

At Julliard we called it Literature and Materials of Music, but it was theory.

I asked him if I could make an appointment for that afternoon, and at one

o’clock I go to this big room where all the theory faculty had desks and

composers had desks; they shared this one big office. So I sit down

at his desk — Vince talked very fast — and he said,

[speaking very quickly] “Well, Harvey, what is it? What is it?

What can I do for you? What’s your problem?” So I poured out

my heart about the literature and I put it on the desk. I said, “Look,

this is all we have! What do I do? I hear so much wonderful

music!” He said, “First of all, all the music ever written belongs

to you as much as it belongs to anybody. It doesn’t matter what it’s

written for. I’m a composer; I speak for all those composers who can’t

speak for themselves. I speak for Bach, I speak for Handel, I speak

for Telemann, I speak for Corelli, I speak for Mozart.” And he goes

on and on. “They want you to play their music and they want you to

play it well. So anytime you hear something that you feel you can present

on the tuba, take it. It belongs to you.” He then continued, “The

second thing I have to say to you,” and he got a little sarcasm in his voice,

“you want better music for the tuba? Well, let me ask you something,

Harvey. Do you think the flute players are going to do something about

it? Do you think the violinists are going to do something about it?

Do you think the conductors are going to do something about it?” He

looked right at me and said, “If you want better music to play on the tuba,

you have to do something about it!” That was my charge. And from

that time on, if I heard an arrangement that I admired, I’d seek that arranger

out. I remember I sought Manny Albam out. I’d heard Zoot Sims

and Al Cohn at Jim and Andy’s, and

I told him how much I admired his writing, but I’d never heard anything he

did that used tuba. He had never used tuba. We became friends

right there at Jim and Andy’s. About a week later I got called for a

recording session, and who’s the conductor on the recording session?

Manny Albam. From that time forward he wrote tuba in everything he did,

and guess who he hired? Me! And not only that, but other arrangers

would hear this. “Hey, Manny’s using tuba!” Monkey see, monkey

do, and I would say within two years after that, about a third of my income

came about from that little conference in Jim and Andy’s.

HP: No, I don’t think so. Think, for example,

of the violin. They are very fortunate to have had great artists such

as Guarneri and Stradivarius who created the ultimate, the nearest thing

to perfect instrument of that kind that could be created. It took our

brass instruments a lot longer because we didn’t even have the valve until

1819. And valves didn’t find their way to the tuba and the other instruments

— so they could be chromatic — until the

middle 1830’s. That’s why we missed out on Beethoven and Bach.

Shortly after I arrived at the Julliard School, I had a practice room assigned

to me for the evening. On my way I passed studios where pianists were

playing Tchaikovsky and violinists were practicing Mendelssohn and Tchaikovsky

and flute players were playing the Handel Flute Sonatas, and horn player was playing

the Mozart Tuba Concertos.

Old Mozart was clairvoyant; he knew some day there’d be tubas, so he wrote

four concertos! [Both laugh uproariously] Then I get to my studio,

take off my coat, take my tuba out of its cover, and put music on the stand

and start going through it. I’ve got Solo Pomposo, Bombasto, Hall of the Mountain King, Down in the Deep Cellar and all this

trite music. I put it back in the briefcase and left. The next

morning I had a class with Vincent Persichetti.

At Julliard we called it Literature and Materials of Music, but it was theory.

I asked him if I could make an appointment for that afternoon, and at one

o’clock I go to this big room where all the theory faculty had desks and

composers had desks; they shared this one big office. So I sit down

at his desk — Vince talked very fast — and he said,

[speaking very quickly] “Well, Harvey, what is it? What is it?

What can I do for you? What’s your problem?” So I poured out

my heart about the literature and I put it on the desk. I said, “Look,

this is all we have! What do I do? I hear so much wonderful

music!” He said, “First of all, all the music ever written belongs

to you as much as it belongs to anybody. It doesn’t matter what it’s

written for. I’m a composer; I speak for all those composers who can’t

speak for themselves. I speak for Bach, I speak for Handel, I speak

for Telemann, I speak for Corelli, I speak for Mozart.” And he goes

on and on. “They want you to play their music and they want you to

play it well. So anytime you hear something that you feel you can present

on the tuba, take it. It belongs to you.” He then continued, “The

second thing I have to say to you,” and he got a little sarcasm in his voice,

“you want better music for the tuba? Well, let me ask you something,

Harvey. Do you think the flute players are going to do something about

it? Do you think the violinists are going to do something about it?

Do you think the conductors are going to do something about it?” He

looked right at me and said, “If you want better music to play on the tuba,

you have to do something about it!” That was my charge. And from

that time on, if I heard an arrangement that I admired, I’d seek that arranger

out. I remember I sought Manny Albam out. I’d heard Zoot Sims

and Al Cohn at Jim and Andy’s, and

I told him how much I admired his writing, but I’d never heard anything he

did that used tuba. He had never used tuba. We became friends

right there at Jim and Andy’s. About a week later I got called for a

recording session, and who’s the conductor on the recording session?

Manny Albam. From that time forward he wrote tuba in everything he did,

and guess who he hired? Me! And not only that, but other arrangers

would hear this. “Hey, Manny’s using tuba!” Monkey see, monkey

do, and I would say within two years after that, about a third of my income

came about from that little conference in Jim and Andy’s. HP: I think what you’re charged with as a performer

is to make the audience happy they came. Even if they’re crying when

they leave, they’re happy they came, and I think a lot of that has to do

with audience contact. When I coach a brass quintet or a chamber group

or even a string quartet — which I’ve done

— when they come on stage, each of them must pick one person in

the audience that they make eye contact with. And continually through

the concert, they make periodic eye contact with that person. Well,

that’s infectious, you know. The audience senses that after a while,

and pretty soon everybody in the audience feels they have eye contact.

When you make eye contact with a member of the audience, you make eye contact

with all of them, and if everyone in the group does that, you win the audience

over. You bring them onstage with you, in effect. You make them

a part of your program. You don’t pull down an invisible screen and

say, “We’re the performers; you’re the audience.” There must be contact,

and the eyes are the best way to do it. Or a smile; not being hokey,

but being genuine. I think that’s the secret of retaining audiences,

and even symphony orchestras can do it. I know the conductor demands

all your attention when he’s conducting, but there are those times between

movements; there are those times when you may have lots of rests, and that

especially happens with the brass players. You’re not going to do

anything that distracts the attention of the audience from the music, but

you’re not going to be a stone statue either. We all have to make

the effort, and not just when you’re performing. When we have a chance

to chat, like we’re having now, even without the microphone and without the

tape recorder, we can have a great time talking about music.

HP: I think what you’re charged with as a performer

is to make the audience happy they came. Even if they’re crying when

they leave, they’re happy they came, and I think a lot of that has to do

with audience contact. When I coach a brass quintet or a chamber group

or even a string quartet — which I’ve done

— when they come on stage, each of them must pick one person in

the audience that they make eye contact with. And continually through

the concert, they make periodic eye contact with that person. Well,

that’s infectious, you know. The audience senses that after a while,

and pretty soon everybody in the audience feels they have eye contact.

When you make eye contact with a member of the audience, you make eye contact

with all of them, and if everyone in the group does that, you win the audience

over. You bring them onstage with you, in effect. You make them

a part of your program. You don’t pull down an invisible screen and

say, “We’re the performers; you’re the audience.” There must be contact,

and the eyes are the best way to do it. Or a smile; not being hokey,

but being genuine. I think that’s the secret of retaining audiences,

and even symphony orchestras can do it. I know the conductor demands

all your attention when he’s conducting, but there are those times between

movements; there are those times when you may have lots of rests, and that

especially happens with the brass players. You’re not going to do

anything that distracts the attention of the audience from the music, but

you’re not going to be a stone statue either. We all have to make

the effort, and not just when you’re performing. When we have a chance

to chat, like we’re having now, even without the microphone and without the

tape recorder, we can have a great time talking about music. HP: I continually try to create opportunities

for those who play my instrument. I’ve always felt that if the tuba

is at the bottom of the musical pyramid, if we elevate the tuba, we raise

the entire pyramid. We’re the foundation and we have to think of ourselves

that way. We have to be tolerant of the general audience who isn’t

educated as yet to the qualities of the tuba. I think we’ve earned

the respect of the audience. Many of the audiences who go to symphony

concerts hear a great tuba solo and don’t realize that it’s the tuba.

If they hear the “Bydlo” from Pictures

at an Exhibition, they think, “Oh, what a beautiful horn sound.”

HP: I continually try to create opportunities

for those who play my instrument. I’ve always felt that if the tuba

is at the bottom of the musical pyramid, if we elevate the tuba, we raise

the entire pyramid. We’re the foundation and we have to think of ourselves

that way. We have to be tolerant of the general audience who isn’t

educated as yet to the qualities of the tuba. I think we’ve earned

the respect of the audience. Many of the audiences who go to symphony

concerts hear a great tuba solo and don’t realize that it’s the tuba.

If they hear the “Bydlo” from Pictures

at an Exhibition, they think, “Oh, what a beautiful horn sound.” BD: Of course, here in Chicago we were spoiled

for forty-four years with Arnold Jacobs...

BD: Of course, here in Chicago we were spoiled

for forty-four years with Arnold Jacobs...|

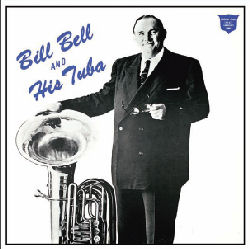

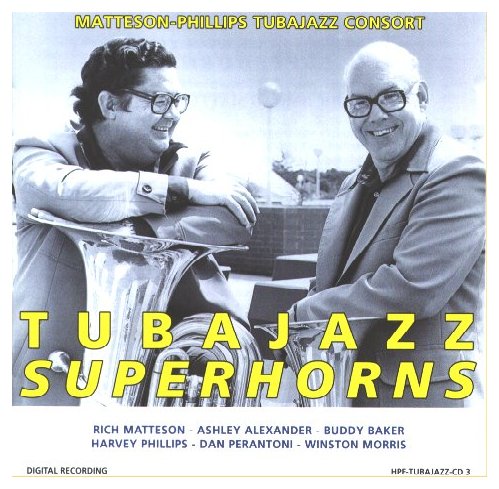

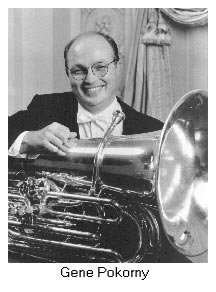

Harvey Phillips is considered by many to be the best tubist in the world. His prodigious technical command of the tuba, musical sense, and rapport with the audience have made him in great demand as a performer. Through his efforts as a teacher, commissioner of new works, and popularizer of the tuba, he has been largely responsible for the present-day renaissance of interest in tuba performance and literature. The youngest of ten children, Harvey was born on December 2, 1929, in Aurora, Missouri, to farmers Jesse and Lottie Phillips. The Phillips lost the family farm due to the Depression and became tenant farmers, finally settling near Marionsville, Missouri. Harvey began to study music in high school with retired circus bandleader Homer Lee, who introduced him to the sousaphone, the rap-around version of the tuba used in marching bands. "I had always wanted to play a brass instrument, but my folks couldn't afford to buy one." Phillips told the News-Sun. "So I fell in love with it. I thought it was the greatest thing that ever happened to me." After graduating in 1947, Phillips got a summer job playing tuba with the King Brothers Circus. Nine weeks later he left to go to the University of Missouri, where he had a scholarship, but he was unhappy there and gladly joined the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Baily Circus band when he received an offer from Merle Evans, the band's leader. Phillips stayed with Ringling Brothers until 1950. His time with the circus proved to be very beneficial as he learned to play many kinds of music to accompany different acts and in his first year he visited every state in the Union. During his second visit to New York City, he met William Bell, then tubist with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. Phillips later studied under Bell, and with his support attended the Juilliard School of Music, in New York, where he received a four-year scholarship. Except for a two-year stint with the U.S. Army Field Band in Washington, D.C., Phillips remained in New York, attending classes at the Manhattan School of Music and performing with a variety of ensembles: the Sauter-Finegan Orchestra, the New York City Opera, the New York City Ballet, and the Goldman Band. Upon the request of Gunther Schuller, then president of the New England Conservatory in Boston, from 1967 to 1971 Phillips served as Schuller's vice-president for financial affairs. During his tenure there, he helped raise more than $6 million to rescue the conservatory from bankruptcy. In 1971 Phillips joined the faculty of the Indiana University School of Music, in Bloomington, upon the retirement and recommendation of Bell, and by 1979 he was made a Distinguished Professor of Music, the highest professorial rank. Phillips has taught many master classes and clinics, been featured at dozens of national and international music conferences, and served on many committees and panels. He strives to instill pride, commitment, and professional ethics in all his students. Phillips aspires to expand performance opportunities in every musical discipline, eradicate musical prejudice and misunderstanding, and broaden the base of audience support for the performing arts. To these ends Phillips organized the Tubists Universal Brotherhood Association (T.U.B.A.), which has a mailing list of 12,000, and other societies to promote brass instruments. He has co-founded such ensembles as Orchestra U.S.A., the New York Brass Quintet, the Matteson-Phillips Tubajazz Consort, and Twentieth Century Innovations, and has performed widely in the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, and Japan. To generate audience support, in 1973 Phillips originated the annual TUBA-CHRISTMAS, which later engendered OCTUBAFEST, TUBAEASTER, and SUMMERTUBAFEST, festivals held across the country to celebrate the tuba. TUBA-CHRISTMAS originated when Phillips wanted to honor his teacher, Bell, who was born on Christmas day. Phillips arranged for tuba players to come to the skating rink at Rockefeller Center to perform Christmas carols in what has now become a tradition. OCTUBAFEST, held annually at Phillips's TUBARANCH in Bloomington, attracts as many as 4,000 participants. Invented in the early 1830s, the tuba was a relative newcomer to the orchestra. It was a vast improvement over its predecessors--the serpent and the ophicleide--and quickly assumed its role in the orchestra. It was not until 1954, however, when Ralph Vaughn Williams composed Concerto for Bass Tuba and Orchestra that the tuba's solo capabilities were made known. Nevertheless, the solo repertoire increased little until Phillips decided to take matters into his own hands. Phillips has been directly responsible for the composition of more than 600 works for tuba. He has inspired, cajoled, and coerced works from many composers--including Vincent Persichetti, Morton Gould, Gunther Schuller, and Alec Wilder--and has directly commissioned more than 100 others. Sometimes payment has taken various forms, such as a case of gin, and when Phillips found himself deeply in debt from commissions and festivals, he set up the Harvey Phillips Foundation to support his musical activities. Indefatigable in his efforts on behalf of the tuba and tubists, Phillips maintains a hectic schedule of performing, teaching, and consulting. Though he is satisfied that people are beginning to appreciate, play, and compose for the tuba with appropriate enthusiasm, he sees no reason to slow his pace. Perhaps Gunther Schuller, a horn player and conductor of renown, who has throughout the years worked with Phillips on many projects, describes him best: "Harvey Phillips is not only a supreme artist on the tuba, but through his multiple activities as a teacher, clinician, commissioner of new works, and organizer of tuba and brass festivals, he has been an indefatigable 'philosopher of the tuba.' His efforts on behalf of other musicians never cease. More than anyone else he has tenaciously proselytized the notion that the tuba can, in the hands of fine musicians, communicate the entire gamut of musical emotions and expressions. For his missionary zeal and his exemplary performance record, Mr. Phillips has won the respect of all his colleagues, as well as countless composers whose works he has premiered, championed and performed. Harvey Phillips, in short, is the major progenitor in his field, and already two generations of younger players are forever indebted to him." by Jeanne M. Lesinski |

This interview was recorded in Chicago on April 24, 1995. Portions

were used (along with recordings) on WNIB three months later, also in 1997

and 1999. The transcription was made and posted on this website in

2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.