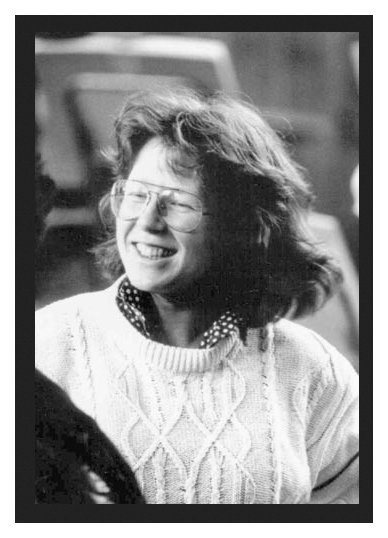

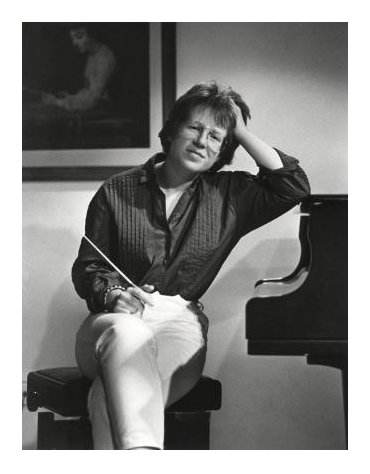

Sian Edwards studied at the RNCM

and with Professor A.I. Musin at the Leningrad Conservatoire. [More about Musin in box farther down on this

webpage.] In September 2013 she took up the role of Head of

Conducting at the Royal Academy of Music. She has worked with many of the

world’s leading orchestras including Los Angeles Philharmonic, Cleveland,

Orchestre de Paris, Ensemble Orchestral de Paris, Berlin Symphony, the Frankfurt

Radio Symphony Orchestra, MDR Leipzig, Vienna Symphony Orchestra, Rotterdam

Philharmonic, Finnish Radio Symphony, St. Petersburg Philharmonic, Royal Flanders

Philharmonic, London Sinfonietta, the Hallé, and City of Birmingham

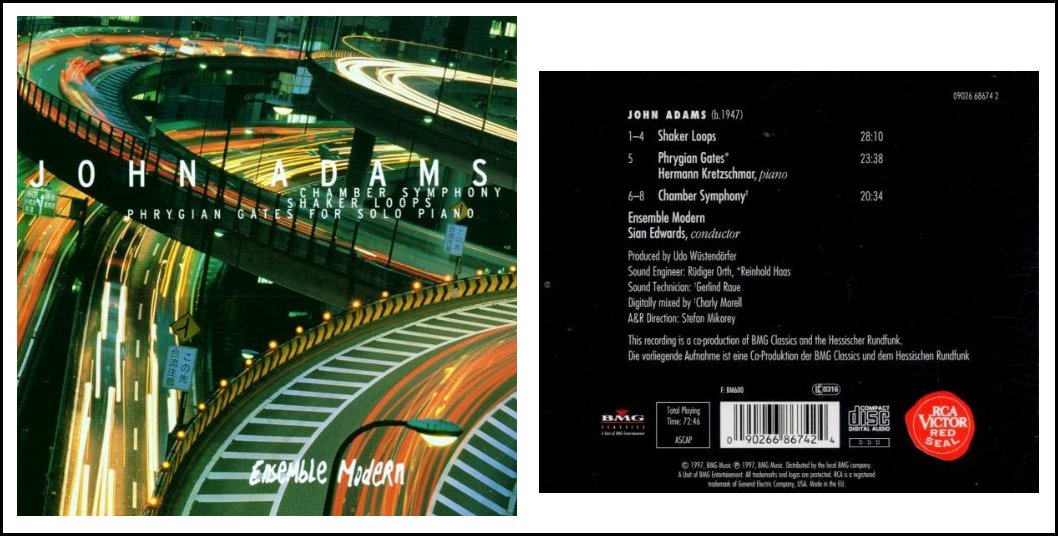

Symphony Orchestra. She has a close relationship with Ensemble

Modern in Germany. She made her operatic debut in 1986 conducting Weill’s Mahagonny for Scottish Opera and her ROH

debut in 1988 with Tippett’s The Knot Garden.

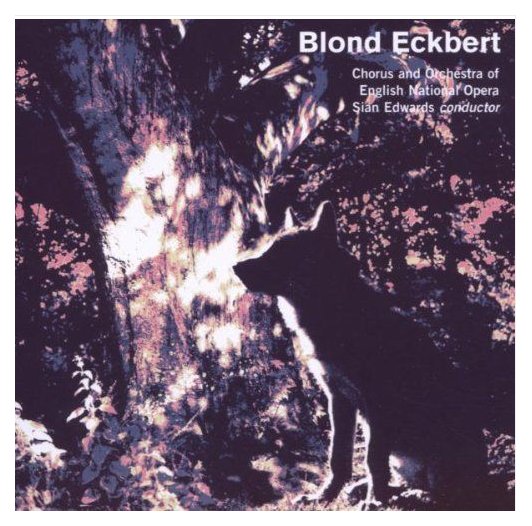

From 1993 to 1995 she was Music Director of ENO (succeeding Mark Elder) for whom her

repertoire included Khovanshchina,

Jenůfa, Queen of Spades and Blond Eckbert (also recorded on Collins).

For the Glyndebourne Festival she has conducted La Traviata and the Ravel Double Bill, and for Glyndebourne Touring

Opera Katya Kabanova and Tippett’s

New Year. She conducted

the world premiere of Mark Anthony Turnage’s Greek at the Munich Biennale in 1988,

and other engagements have included the world premiere of Hans Gefors’ Clara for the Opéra Comique in

Paris, Così fan tutte in

Aspen, her return to ENO for Eugene Onegin,

Don Giovanni in Copenhagen,

Damnation de Faust in Helsinki,

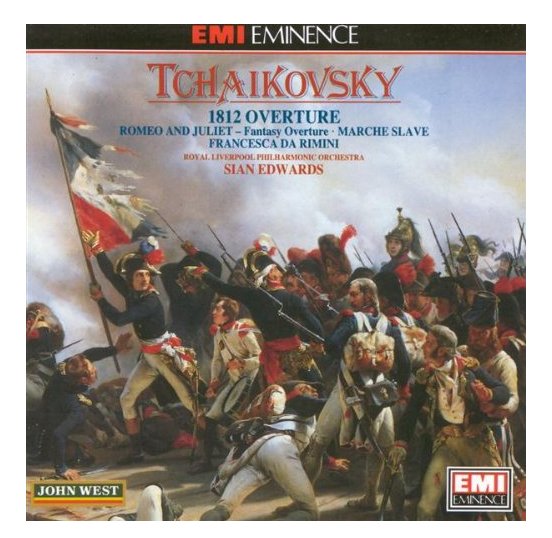

Peter Grimes and Tchaikovsky’s

Queen of Spades in Frankfurt;

Previn’s A Streetcar Named Desire and Heggie’s

Dead Man Walking at the Theater

an der Wien, A Night at the Chinese

Opera for Scottish Opera, Jenůfa

for Welsh National Opera, Hansel and Gretel

for the Royal Academy of Music and Aquarius

by Karel Goeyvaerts for Flanders Opera.

She made her operatic debut in 1986 conducting Weill’s Mahagonny for Scottish Opera and her ROH

debut in 1988 with Tippett’s The Knot Garden.

From 1993 to 1995 she was Music Director of ENO (succeeding Mark Elder) for whom her

repertoire included Khovanshchina,

Jenůfa, Queen of Spades and Blond Eckbert (also recorded on Collins).

For the Glyndebourne Festival she has conducted La Traviata and the Ravel Double Bill, and for Glyndebourne Touring

Opera Katya Kabanova and Tippett’s

New Year. She conducted

the world premiere of Mark Anthony Turnage’s Greek at the Munich Biennale in 1988,

and other engagements have included the world premiere of Hans Gefors’ Clara for the Opéra Comique in

Paris, Così fan tutte in

Aspen, her return to ENO for Eugene Onegin,

Don Giovanni in Copenhagen,

Damnation de Faust in Helsinki,

Peter Grimes and Tchaikovsky’s

Queen of Spades in Frankfurt;

Previn’s A Streetcar Named Desire and Heggie’s

Dead Man Walking at the Theater

an der Wien, A Night at the Chinese

Opera for Scottish Opera, Jenůfa

for Welsh National Opera, Hansel and Gretel

for the Royal Academy of Music and Aquarius

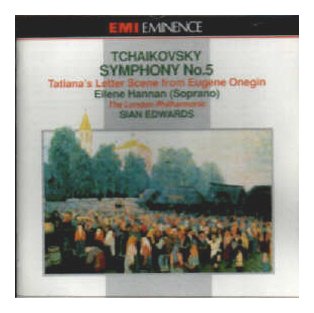

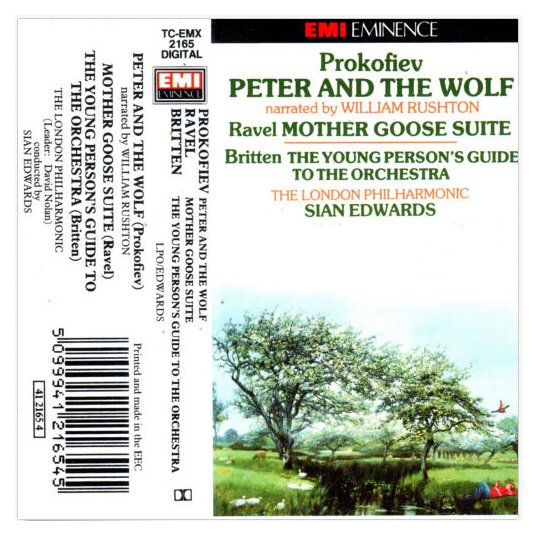

by Karel Goeyvaerts for Flanders Opera.Sian Edwards’ recordings include Peter and the Wolf, Britten’s Young Person’s Guide, and Tchaikovsky’s 5th Symphony, all with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Judith Weir’s Blond Eckbert with English National Opera. Recent and future concert engagements include performances with Ensemble Modern, Bayerische Rundfunk in Munich, SWR Sinfonieorchester Freiburg, Kuopio Symphony, Turku Philharmonic, Frankfurt Radio Symphony, Orquesta Sinfonica de Galicia, musikfabrik, Landesjugendorchester Berlin, Deutscher Musikrat, Milton Keynes City Orchestra, Palestinian Youth Orchestra, Edinburgh Youth Orchestra, London Sinfonietta, BBC National Orchestra of Wales as well as performances at the Edinburgh International Festival, the Royal College of Music and a tour of the UK with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in honour of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee . Recent and future operatic engagements include The Rape of Lucretia and La traviata for the Theater an der Wien, Orlando, a new ballet, for the Staatstheater Stuttgart, The Rake’s Progress for Scottish Opera, Ades’ The Tempest for Oper Frankfurt, and a concert performance of Tippett’s King Priam at the Brighton Festival. She has recently contributed to a new film by Tony Palmer on Holst. -- Biography from Ingpen &

Williams website (with slight additions)

-- Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

SE: Having had this experience at English National

Opera, I can say that eventually I would love actually to work again with

an ensemble or a company long-term, but it would be very important to me

that I mainly did the conducting and some of the planning, but not everything

else that was happening. I’m very happy to be around and take part

in various events, but not to the extent of having to work on reshaping the

whole working mode of the company, which is what ENO was going through a

few years ago. That really does get too much.

SE: Having had this experience at English National

Opera, I can say that eventually I would love actually to work again with

an ensemble or a company long-term, but it would be very important to me

that I mainly did the conducting and some of the planning, but not everything

else that was happening. I’m very happy to be around and take part

in various events, but not to the extent of having to work on reshaping the

whole working mode of the company, which is what ENO was going through a

few years ago. That really does get too much. BD: But when we look at tapes of the conductors

of the previous generations, such as Toscanini and Furtwängler, those

kinds of antics and ideas may or may not be acceptable today.

BD: But when we look at tapes of the conductors

of the previous generations, such as Toscanini and Furtwängler, those

kinds of antics and ideas may or may not be acceptable today. SE: [Laughs] That’s a very good question!

There are certain things for me that are fairly straightforward. I’m

not at all — at the moment anyway — a

baroque or classical specialist. I wasn’t brought up on early music

in any way, so that is now such a particular field that I don’t feel equipped

to do. I would do Bach or Handel with small orchestras so I can try

things out, but I suppose my repertoire really starts with Haydn and Mozart.

I don’t work in the classical style particularly in that I’ve never worked

with an orchestra that plays period instruments, for example. But

I have learned a lot from what I’ve heard from performances they give, and

indeed I think that performance style is gradually working its way into the

mainstream in lots of different areas. But I always say that I start

with Haydn, and it’s a fairly mainstream view of that music. I really

love to do Beethoven, and want to do more.

SE: [Laughs] That’s a very good question!

There are certain things for me that are fairly straightforward. I’m

not at all — at the moment anyway — a

baroque or classical specialist. I wasn’t brought up on early music

in any way, so that is now such a particular field that I don’t feel equipped

to do. I would do Bach or Handel with small orchestras so I can try

things out, but I suppose my repertoire really starts with Haydn and Mozart.

I don’t work in the classical style particularly in that I’ve never worked

with an orchestra that plays period instruments, for example. But

I have learned a lot from what I’ve heard from performances they give, and

indeed I think that performance style is gradually working its way into the

mainstream in lots of different areas. But I always say that I start

with Haydn, and it’s a fairly mainstream view of that music. I really

love to do Beethoven, and want to do more.  BD: Are we getting better at that?

BD: Are we getting better at that? SE: This is my eleventh professional season, but

earlier on when I first started working, I more or less took on everything

that was offered because for me it was a great trial period. A lot

of the time you have an instinct about certain composers, but other pieces

you really don’t know whether you’re going to do them well or like them until

you’ve done them. So I’ve had a long period of doing a lot of things,

and it’s only now that I’m beginning to draw back a little bit and say that

we don’t get on with that sort of thing, or know that I can do this quite

well. I’ve done some pieces which are rhythmically incredibly complicated

and ended up being something where you don’t hear or feel a rhythm, and

when you’re listening to it it’s a complex web of sound. I find those

pieces very difficult to do, and pretty stressful as well. So I suppose

I’m gradually beginning to see that I don’t do those so well. But

on the other hand, I did a couple of pieces by Swiss composers recently

at a Lucerne Festival, and they were obviously straight away pieces I could

tackle. One was quite lyrical and more Debussy-like in its color,

and the other one was very rhythmic and more minimalist, and which was fun

as well. Both were with choirs, and I enjoyed that a lot.

SE: This is my eleventh professional season, but

earlier on when I first started working, I more or less took on everything

that was offered because for me it was a great trial period. A lot

of the time you have an instinct about certain composers, but other pieces

you really don’t know whether you’re going to do them well or like them until

you’ve done them. So I’ve had a long period of doing a lot of things,

and it’s only now that I’m beginning to draw back a little bit and say that

we don’t get on with that sort of thing, or know that I can do this quite

well. I’ve done some pieces which are rhythmically incredibly complicated

and ended up being something where you don’t hear or feel a rhythm, and

when you’re listening to it it’s a complex web of sound. I find those

pieces very difficult to do, and pretty stressful as well. So I suppose

I’m gradually beginning to see that I don’t do those so well. But

on the other hand, I did a couple of pieces by Swiss composers recently

at a Lucerne Festival, and they were obviously straight away pieces I could

tackle. One was quite lyrical and more Debussy-like in its color,

and the other one was very rhythmic and more minimalist, and which was fun

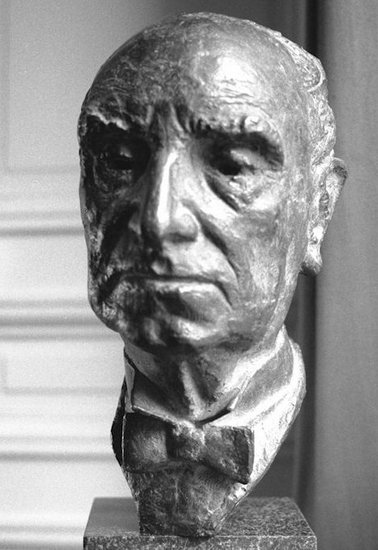

as well. Both were with choirs, and I enjoyed that a lot. Ilya Aleksandrovich Musin

(Russian: Илья́ Алекса́ндрович Му́син; 6 January 1904 [O.S. 24 December 1903]

– 6 June 1999) was a Russian conductor, a prominent teacher and a theorist

of conducting.

Ilya Aleksandrovich Musin

(Russian: Илья́ Алекса́ндрович Му́син; 6 January 1904 [O.S. 24 December 1903]

– 6 June 1999) was a Russian conductor, a prominent teacher and a theorist

of conducting.Musin first studied conducting under Nikolai Malko and Aleksandr Gauk. He became assistant to Fritz Stiedry with the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra in 1934. The Soviet government later sent him to lead the State Belarusian Orchestra, but then curtailed his conducting career because he never joined the Soviet Communist Party. He turned to teaching, creating a school of conducting that is still referred to as the "Leningrad school of conducting". He spent 1941–45 in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, where most Russian intellectuals were kept safe during the war. There he continued conducting and teaching. On June 22, 1942, the anniversary of the Nazi invasion, he conducted the second performance of Shostakovich's Leningrad Symphony. In 1932 Musin was invited to teach conducting at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, then known as the Leningrad Conservatory. He developed a comprehensive theoretical system to enable the student to communicate with the orchestra with the hands, requiring minimal verbal instruction. No one had previously formulated such a detailed and clear system of conducting gestures. Apparently, his own early experiences as a student had prompted him to study the intricacies of manual technique. When Musin tried to enter Malko's conducting class at the Leningrad Conservatory in 1926, he had been denied entrance because of poor manual technique. He pleaded with Malko to be accepted provisionally, and eventually became an authority on manual technique, describing his system in his book The Technique of Conducting. Musin described the main principle of his method in these words: "A conductor must make music visible to his musicians with his hands. There are two components to conducting, expressiveness and exactness. These two components are in dialectical opposition to each other; in fact, they cancel each other out. A conductor must find the way to bring the two together." Over a teaching career spanning 60 years, his students included Rudolf Barshai, Semyon Bychkov, Tugan Sokhiev, Sabrie Bekirova, Oleg Caetani, Vassily Sinaisky, Konstantin Simeonov, Odysseas Dimitriadis, Vladislav Chernushenko, Victor Fedotov, Leonid Shulman, Arnold Katz, Andrey Tchistyakov, Sian Edwards, Martyn Brabbins, Kim Ji Hoon, Peter Jermihov, Alexander Walker, John Landor, Yuri Temirkanov, Valery Gergiev, Ennio Nicotra, Leonid Korchmar and Oleg Proskurnya (who assisted Musin with the International Conducting Workshop and founded the International Academy of Advanced Conducting after Ilya Musin). |

SE: Good God! [Huge laugh] That is

a big one... It’s there! Music is around us in every context,

especially nowadays. You go in any shop or any restaurant, there is

music. It is in the airports and on airplanes, they play you music when

you take off to calm you down. If music can communicate any kind of

feelings, emotions, a sense of a different world, a different landscape of

emotional experience perhaps, involve people at all in a way that touches

them in an area that their usual lives don’t move in, then it’s done its job,

whatever kind of music it is. There’s music in shopping malls to calm

us down, and perhaps that’s okay because we need calming down. I sometimes

find that all too much actually, I must say. I’m not a great ‘Muzak’

fan.

SE: Good God! [Huge laugh] That is

a big one... It’s there! Music is around us in every context,

especially nowadays. You go in any shop or any restaurant, there is

music. It is in the airports and on airplanes, they play you music when

you take off to calm you down. If music can communicate any kind of

feelings, emotions, a sense of a different world, a different landscape of

emotional experience perhaps, involve people at all in a way that touches

them in an area that their usual lives don’t move in, then it’s done its job,

whatever kind of music it is. There’s music in shopping malls to calm

us down, and perhaps that’s okay because we need calming down. I sometimes

find that all too much actually, I must say. I’m not a great ‘Muzak’

fan. BD: So it wasn’t just the music, it was also the

logistics?

BD: So it wasn’t just the music, it was also the

logistics?

© 1996 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at her hotel in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on September 19, 1996. Portions were broadcast on WNIB 1999. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.