|

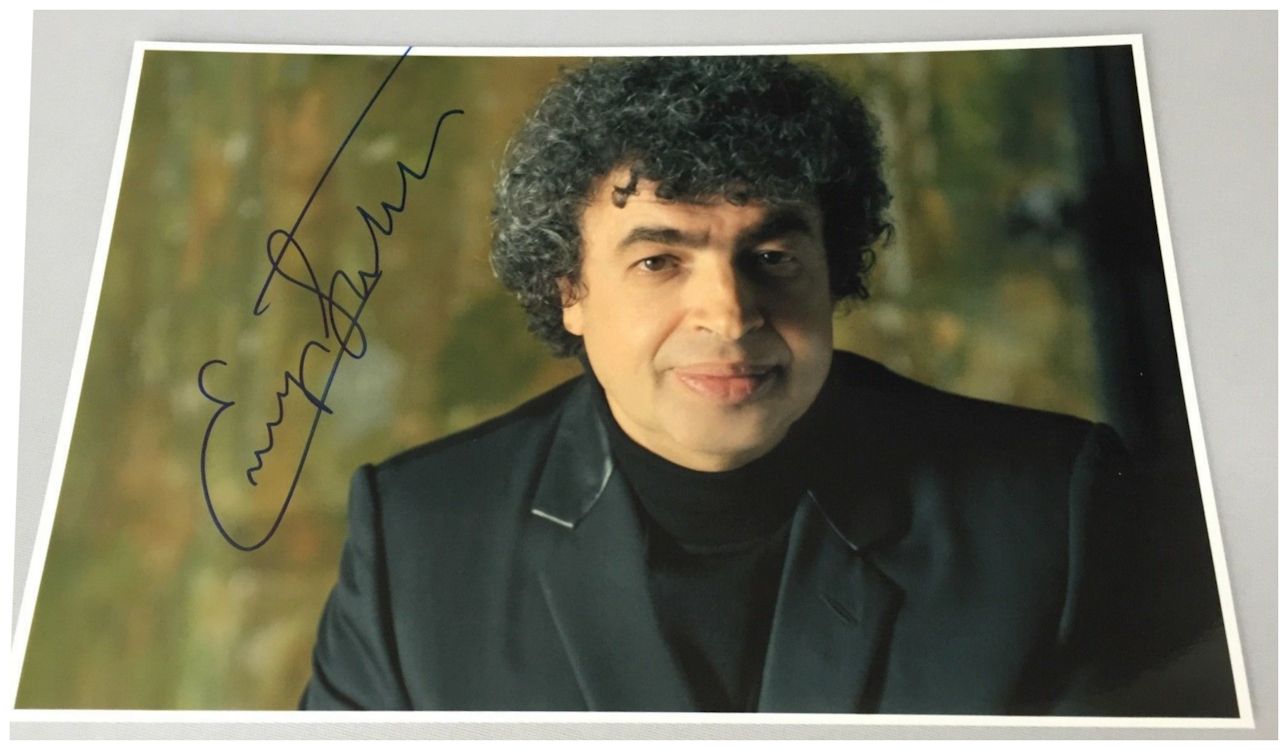

Born in St. Petersburg in 1952, Semyon Bychkov immigrated to the United States in 1975 and has been based in Europe since the mid-1980s. In common with the Czech Philharmonic, of which he became Music Director in 2018, Bychkov has one foot firmly in the cultures both of the East and the West. Following his early concerts with the Orchestra in 2013, Bychkov devised The Tchaikovsky Project, a series of concerts, residencies and studio recordings which allowed them the luxury of exploring Tchaikovsky’s music together, both in Prague’s Rudolfinum and abroad. Bychkov won the Rachmaninov Conducting Competition when he was 20 years old. Two years later, having been denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, he left the former Soviet Union where, from the age of five he was singled out for an extraordinarily privileged musical education. Starting with piano, Bychkov was later selected to study at the Glinka Choir School where he received his first conducting lesson aged 13. Four years later he was accepted at the Leningrad Conservatory as a student of the legendary Ilya Musin. By the time Bychkov returned to St. Petersburg in 1989 as the Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor, he had enjoyed success in the US as Music Director of the Grand Rapids Symphony Orchestra and the Buffalo Philharmonic. His international career, which began in France with Opéra de Lyon and at the Aix-en-Provence Festival, took off with a series of high-profile cancellations which resulted in invitations to conduct the New York Philharmonic, Berlin Philharmonic and Royal Concertgebouw Orchestras. In 1989, he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris; in 1997, Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne; and the following year, Chief Conductor of the Dresden Semperoper. Bychkov’s symphonic and operatic repertoire

is wide-ranging. He conducts in all the major houses including La Scala,

Opéra national de Paris, Dresden Semperoper, Wiener Staatsoper, New

York’s Metropolitan Opera, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden and Teatro

Real. Madrid. While Principal Guest Conductor of Maggio Musicale Fiorentino,

his productions of Janáček’s Jenůfa, Schubert’s Fierrabras,

Puccini’s La bohème, Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth

of Mtsensk and Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov each won the prestigious

Premio Abbiati. In 2018, he conducted Wagner’s Parsifal both

at the Wiener Staatsoper and Bayreuth. Other new productions in Vienna

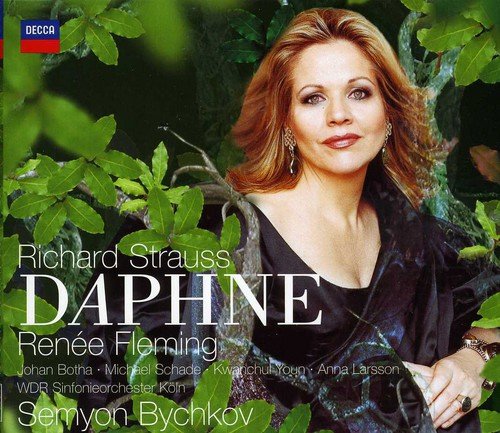

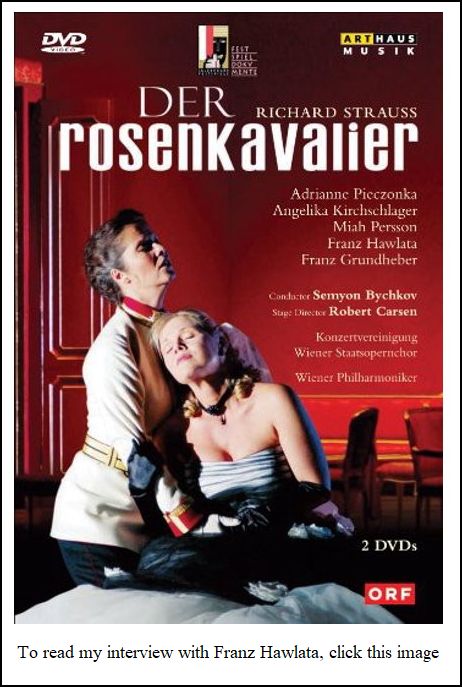

include Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier and Daphne, Wagner’s

Lohengrin and Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina; while in

London, he made his debut with a new production of Strauss’ Elektra,

and subsequently conducted new productions of Mozart’s Così fan

tutte [DVD cover shown below], Strauss’ Die Frau ohne Schatten

and Wagner’s Tannhäuser.

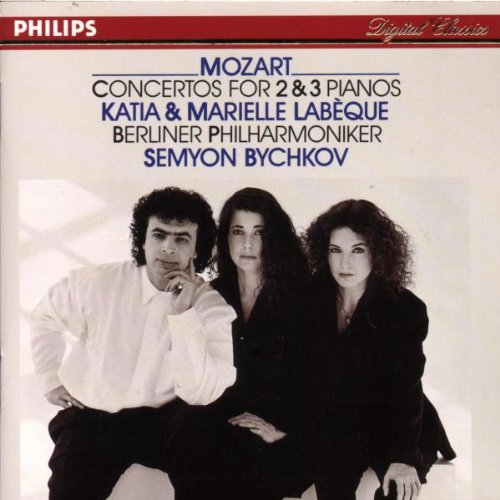

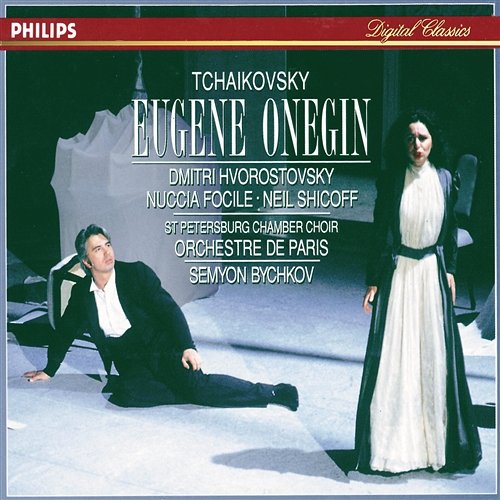

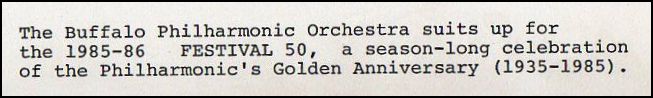

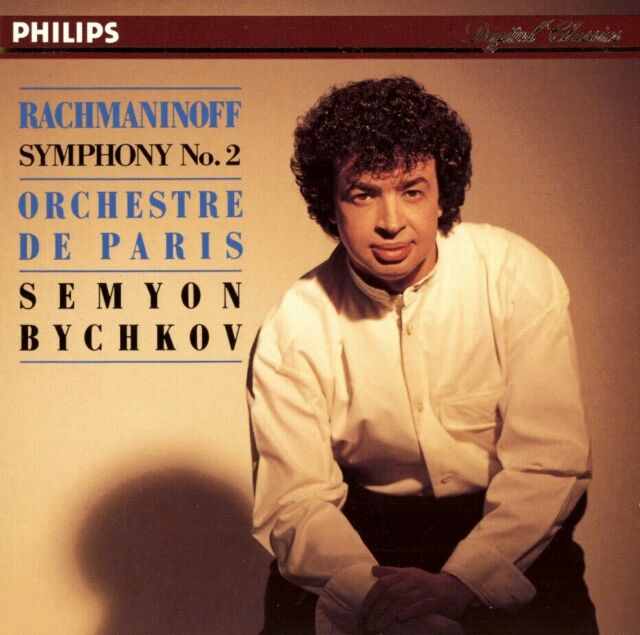

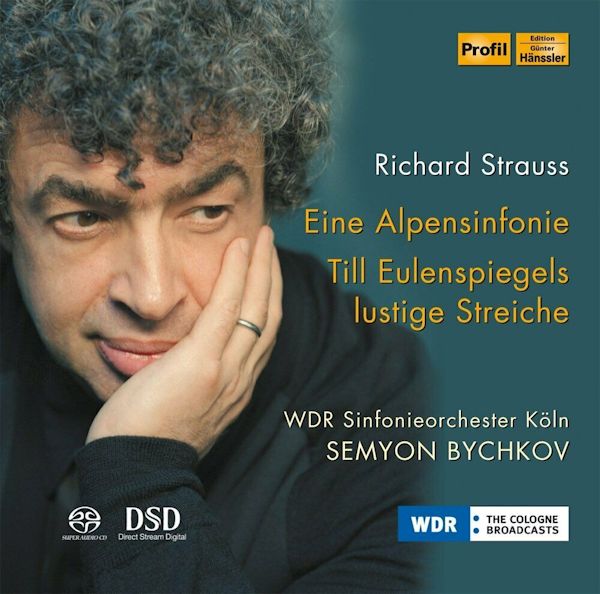

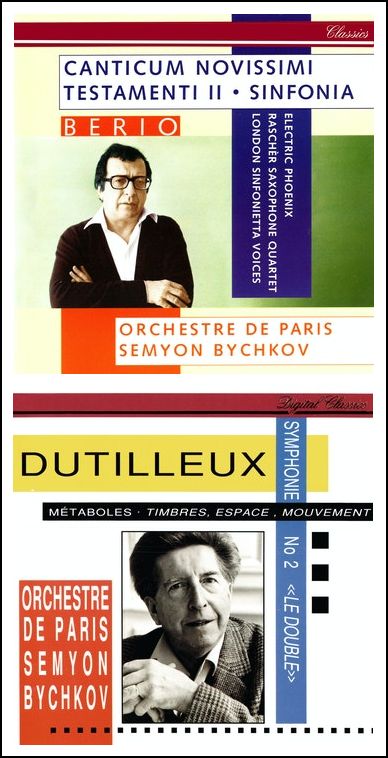

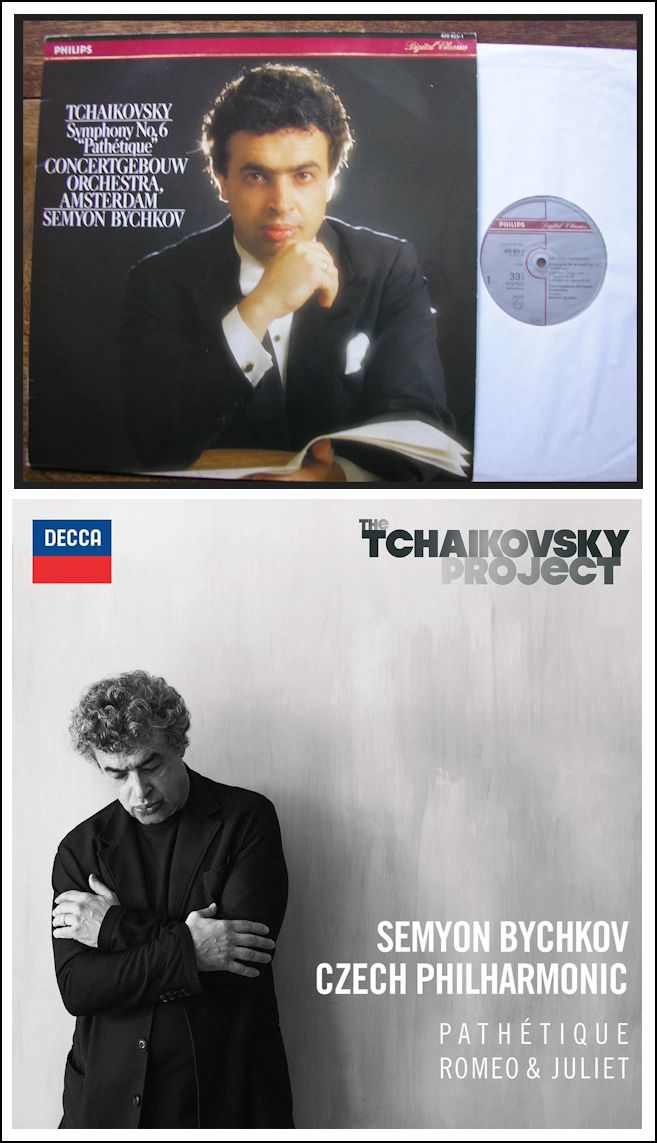

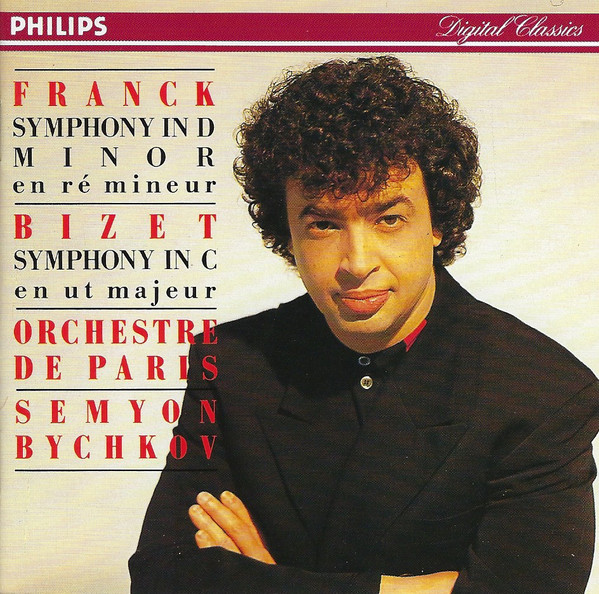

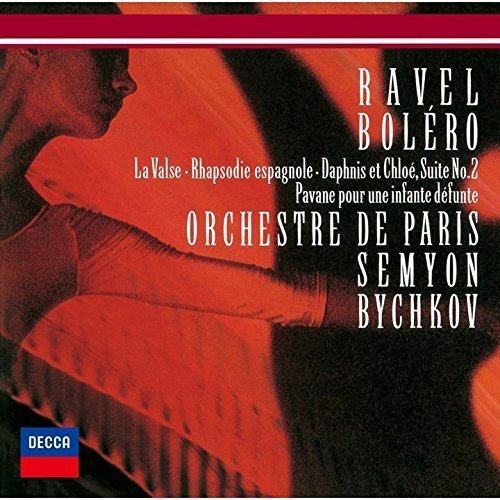

Recognised for his interpretations of the core repertoire, Bychkov has worked closely with many extraordinary contemporary composers including Luciano Berio, Henri Dutilleux and Maurizio Kagel. In recent seasons he has worked closely with René Staar, Thomas Larcher, Richard Dubignon, Detlev Glanert and Julian Anderson, conducting premières of their works with the Vienna Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Royal Concertgebouw and the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the BBC Proms. Bychkov’s recording career began in 1986 when he signed with Philips and began a significant collaboration which produced an extensive discography with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia, London Philharmonic and Orchestre de Paris. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings – the result of his 13-year collaboration (1997-2010) with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne – include a complete cycle of Brahms Symphonies, and works by Strauss (Elektra, Daphne, Ein Heldenleben, Metamorphosen, Alpensinfonie, Till Eulenspiegel), Mahler (Symphony No. 3, Das Lied von der Erde), Shostakovich (Symphony Nos. 4, 7, 8, 10, 11), Rachmaninov (The Bells, Symphonic Dances, Symphony No. 2), Verdi (Requiem), Detlev Glanert and York Höller. His recording of Wagner’s Lohengrin was voted BBC Music Magazine’s Disc of the Year in 2010; his recording of César Franck’s Symphony in D minor was the Recommended Recording of BBC Radio 3’s Record Review’s Building a Library; and his recent recording of Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was selected as BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month. Bychkov was named 2015’s Conductor of

the Year by the International Opera Awards.

== Text of biography from IMG Artists

|

BD: Did you get interested because of

going to performances, or listening to recordings?

BD: Did you get interested because of

going to performances, or listening to recordings? BD: Isn’t that an awful lot of responsibility

to place on very young shoulders?

BD: Isn’t that an awful lot of responsibility

to place on very young shoulders? BD: How much of your work is done in the rehearsal, and

how much inspiration do you leave for that night of performance?

BD: How much of your work is done in the rehearsal, and

how much inspiration do you leave for that night of performance?

BD: Coming back to the story, you won the Rachmaninov

Competition. What did that lead to?

BD: Coming back to the story, you won the Rachmaninov

Competition. What did that lead to? Bychkov: New York. I lived there

for five years, and I went to the Mannes College of Music.

Bychkov: New York. I lived there

for five years, and I went to the Mannes College of Music. Bychkov: Basically, it’s a way of amusement.

It’s a way of resting and enjoying the situation. We all enjoyed

being entertained, and it’s great, but art has to be more than just

giving a good time to a person. It has to be a challenge. Often

it has to be disturbing to a people who are receiving it. It has

to make them think. It has to make them feel. It has to make

them want to know more about it, and that’s not just entertainment.

It goes much deeper than that.

Bychkov: Basically, it’s a way of amusement.

It’s a way of resting and enjoying the situation. We all enjoyed

being entertained, and it’s great, but art has to be more than just

giving a good time to a person. It has to be a challenge. Often

it has to be disturbing to a people who are receiving it. It has

to make them think. It has to make them feel. It has to make

them want to know more about it, and that’s not just entertainment.

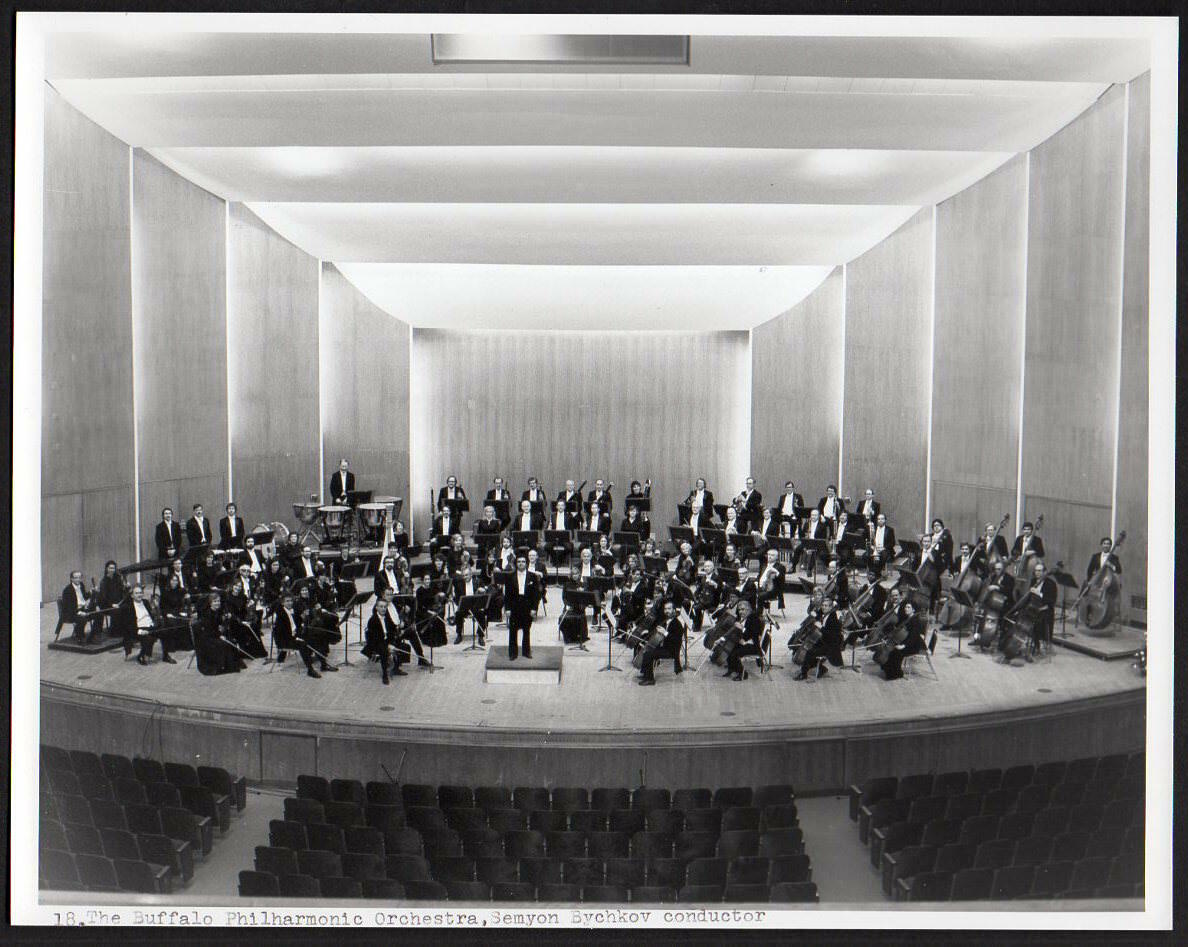

It goes much deeper than that. Bychkov: Most of my time goes to the

orchestra with which I’m associated. For the moment it is Buffalo,

and then as far as guest conducting is concerned, there is a limited time

for that. I have to have enough time to study, and to think about

the music, and experience life, in other words just to live. There

are maybe four orchestras that I permanently guest conduct every year, and

as far as opera is concerned, on the average I’m able to do one production

a year, normally in the summer, in the festival environment. That’s

how the time is divided.

Bychkov: Most of my time goes to the

orchestra with which I’m associated. For the moment it is Buffalo,

and then as far as guest conducting is concerned, there is a limited time

for that. I have to have enough time to study, and to think about

the music, and experience life, in other words just to live. There

are maybe four orchestras that I permanently guest conduct every year, and

as far as opera is concerned, on the average I’m able to do one production

a year, normally in the summer, in the festival environment. That’s

how the time is divided. Bychkov: No, no. It’s a fantastic process to make

a record, because in the back of your mind you know that you can always

stop and repeat something. So, you don’t mind this mistake here or

there. It really doesn’t matter. Also, you have a chance to

hear it back. It’s like looking at yourself in the mirror. All

you have to do is open your eyes when you look in a mirror, or open your

ears when you listen. However, sometimes that is a hard thing to do,

because when you’re doing it at the moment you’re actually working, you’re

listening to it in a different way than when you’re removed from it. Then,

two months later you’re going to hear the tempo, and it will not feel

the same as it did when you were doing it. You go through various

stages of acceptance and rejection, but it is really no different.

What I don’t like from records is when they are made in a very clinical

way. They have no mistakes, and things are absolutely perfect. All

the notes are played, but you don’t feel there is a spirit in the music-making

that makes you sit up and listen. It’s something that you look for

in a live performance, otherwise you will be bored, and you should be able

to get the same thing in a recorded performance.

Bychkov: No, no. It’s a fantastic process to make

a record, because in the back of your mind you know that you can always

stop and repeat something. So, you don’t mind this mistake here or

there. It really doesn’t matter. Also, you have a chance to

hear it back. It’s like looking at yourself in the mirror. All

you have to do is open your eyes when you look in a mirror, or open your

ears when you listen. However, sometimes that is a hard thing to do,

because when you’re doing it at the moment you’re actually working, you’re

listening to it in a different way than when you’re removed from it. Then,

two months later you’re going to hear the tempo, and it will not feel

the same as it did when you were doing it. You go through various

stages of acceptance and rejection, but it is really no different.

What I don’t like from records is when they are made in a very clinical

way. They have no mistakes, and things are absolutely perfect. All

the notes are played, but you don’t feel there is a spirit in the music-making

that makes you sit up and listen. It’s something that you look for

in a live performance, otherwise you will be bored, and you should be able

to get the same thing in a recorded performance. Bychkov: Every once in a long while

you are lucky that somehow all the components happen, and then you feel

absolutely incredible. Those are the memorable ones. That

is not to say that if things are going wrong in the performance, you’re

not going to be a hundred per cent happy. You’re going try to do it

better next time, and what can happen is that a particular point of difficulty

that one had will be overcome... but something else might go wrong.

It’s not really the thing on which one needs to base one’s acceptance or

lack of it about the performance. It’s something that we constantly

work on, and no one is happy. Do you think a horn player is happy when

he cracks a note in an important solo? He’s miserable there. But

if he will allow himself to be so depressed that nothing else will matter

to him, he’s going to crack the next note, and the note after that, and

it’s going to be a complete disaster. He has to recover, and just feel

okay. So what? It’s all right. It happens to everyone.

Bychkov: Every once in a long while

you are lucky that somehow all the components happen, and then you feel

absolutely incredible. Those are the memorable ones. That

is not to say that if things are going wrong in the performance, you’re

not going to be a hundred per cent happy. You’re going try to do it

better next time, and what can happen is that a particular point of difficulty

that one had will be overcome... but something else might go wrong.

It’s not really the thing on which one needs to base one’s acceptance or

lack of it about the performance. It’s something that we constantly

work on, and no one is happy. Do you think a horn player is happy when

he cracks a note in an important solo? He’s miserable there. But

if he will allow himself to be so depressed that nothing else will matter

to him, he’s going to crack the next note, and the note after that, and

it’s going to be a complete disaster. He has to recover, and just feel

okay. So what? It’s all right. It happens to everyone. Bychkov: Again, this is a value judgement, and a very

personal point of view. Music written by Shostakovich, for me

is as important as Brahms, Beethoven, and Bach. There are not many

more of the composers of our time that I could say that about, but one

ought to be open enough to understand that it really takes time.

One needs to have the time and the perspective to look at it before deciding

on that. If I listen to music of Luciano Berio, that it

is something absolutely incredible, really great, interesting, and quite

magnificent. And, if I don’t understand it completely right away,

I still feel that there is something there that I simply have to take

time to know, and that’s what I do, in fact. That applies to many

others like, Lutosławski, and Boulez, and Dutilleux,

and Henze.

Bychkov: Again, this is a value judgement, and a very

personal point of view. Music written by Shostakovich, for me

is as important as Brahms, Beethoven, and Bach. There are not many

more of the composers of our time that I could say that about, but one

ought to be open enough to understand that it really takes time.

One needs to have the time and the perspective to look at it before deciding

on that. If I listen to music of Luciano Berio, that it

is something absolutely incredible, really great, interesting, and quite

magnificent. And, if I don’t understand it completely right away,

I still feel that there is something there that I simply have to take

time to know, and that’s what I do, in fact. That applies to many

others like, Lutosławski, and Boulez, and Dutilleux,

and Henze. Bychkov: [Thinks again] I

don’t feel very well about giving advice to other people, in the sense

that different people need different kinds of advice. There is nothing

that is universally good that I feel I should say that would not sound

pompous and condescending. I would say what I say to every musician,

or every person who wants to apply himself to something, simply to do it

honestly, and with total commitment. Not to do it half-way, and try

to realize if it’s something that the person has a special talent for.

Sometimes that is a very difficult thing, because being obsessed about

something and having a special talent to do it is not the same thing. It’s

very difficult for a person to know which is which, but that’s not something

I could give advice on. Each person should decide for himself.

Bychkov: [Thinks again] I

don’t feel very well about giving advice to other people, in the sense

that different people need different kinds of advice. There is nothing

that is universally good that I feel I should say that would not sound

pompous and condescending. I would say what I say to every musician,

or every person who wants to apply himself to something, simply to do it

honestly, and with total commitment. Not to do it half-way, and try

to realize if it’s something that the person has a special talent for.

Sometimes that is a very difficult thing, because being obsessed about

something and having a special talent to do it is not the same thing. It’s

very difficult for a person to know which is which, but that’s not something

I could give advice on. Each person should decide for himself. Bychkov: Yes, tremendously. I

enjoy less listening to them after they’re made because there is nothing

I can do about it once it’s done. But the process of doing it, I enjoy

very much.

Bychkov: Yes, tremendously. I

enjoy less listening to them after they’re made because there is nothing

I can do about it once it’s done. But the process of doing it, I enjoy

very much. Bychkov: Yes.

Bychkov: Yes. BD: Do they have veto power?

BD: Do they have veto power?

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 28, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1992, 1999, and 2000; and on WNUR in 2004. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.