A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

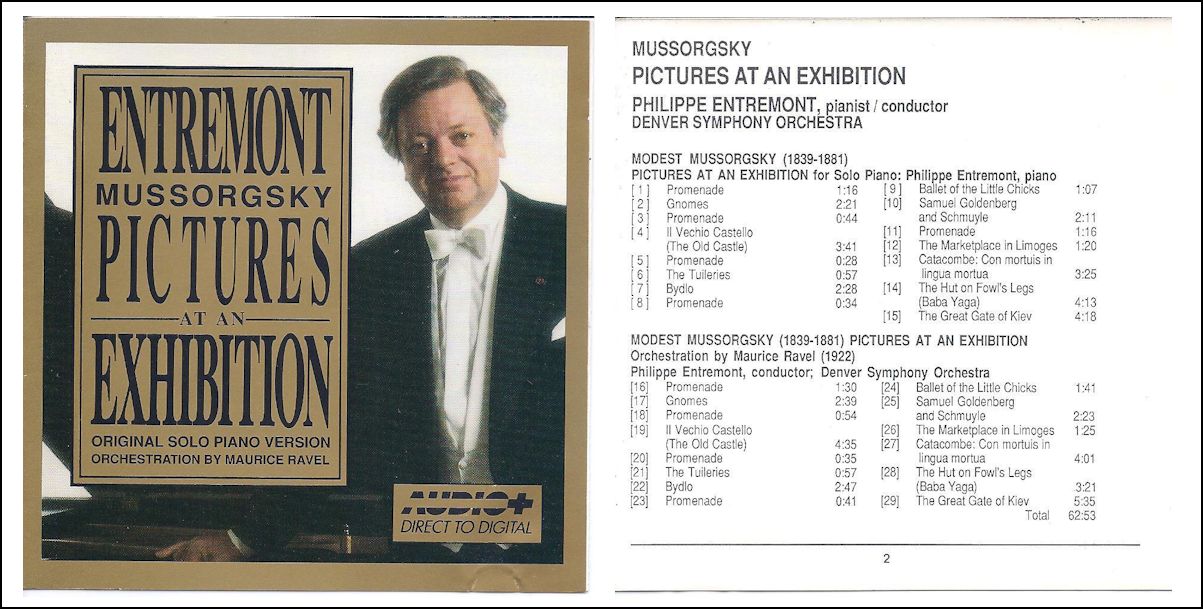

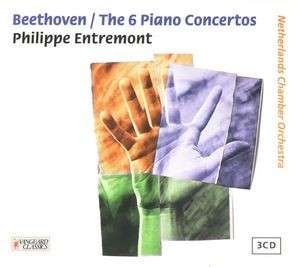

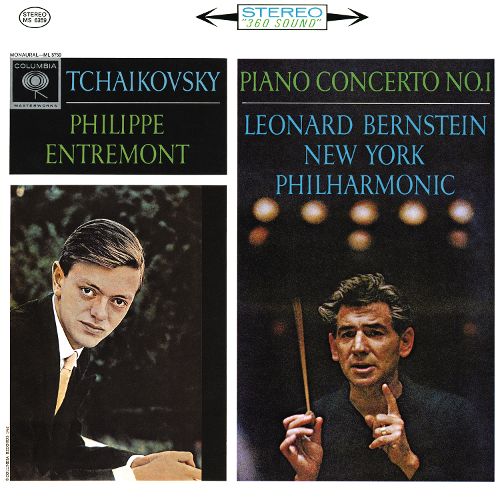

Philippe Entremont was born in Reims on June 7, 1934, to musical parents, his mother being a Grand Prix pianist and his father an operatic conductor. Philippe first received piano lessons from his mother at the age of six. His father introduced him to the world of chamber and orchestral music. He studied in Paris with Marguerite Long, and entered the Conservatoire de Paris. He won prizes in sight-reading at age 12, chamber-music aged 14, and piano at 15. He became Laureat at the international Long-Thibaud Competition at the age of 16. His international career began at the age of eighteen when he came to attention with his great success at New York’s Carnegie Hall playing Jolivet’s Piano Concerto and Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 1. Since then, he has pursued a top international career as a pianist, and for the last 30 years, on the podium as well.His renown as an orchestral conductor and his dedication to developing orchestras’ artistic potential have led to numerous international tours, playing before full houses: ten tours in the US and seven in Japan with the Vienna Chamber Orchestra, a tour of eleven concerts with the Orquestra de Cadaqués in capitals of countries in Asia, and a tour in Switzerland and Germany conducting the Strasbourg Philharmonic Orchestra. As Principal Guest Conductor of the Munich Symphony Orchestra, he has led tours internationally, including the US in 2005 and 2006, conducting from the piano as well as the podium. He returned in both capacities for the Munich Symphony’s highly successful 15-concert US tour in February of 2009. In 1997, Entremont founded the biennial Santo Domingo Music Festival, of which he is Artistic Director and Conductor of the Festival Orchestra. The Festival celebrated its 10th anniversary in 2007 with a special concert series featuring the premieres of two Festival-commissioned symphonies by Dominican composers, and performances by internationally renowned guest artists such as André Watts, Dan Zhu, Arturo Sandoval, Sir James Galway, Teresa Berganza, Maxim Vengerov, and Vitalij Kowaljow. He is also Principal Guest Conductor of the Orquestra de Cadaqués. In 2006, in connection with the “Mozart Year,” he conducted the Tokyo-based Super World Orchestra. Philippe Entremont was also among the 10 world-class pianists chosen to perform in the “Piano Extravaganza of the Century” at the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games [see article in box below]. Entremont was Music Director of the New Orleans Philharmonic Orchestra between 1981 and 1986, after which he became Music Director of the Denver Symphony. He was also Chief Conductor of the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra until 2002. After having served as Music Director and Chief Conductor of the Vienna Chamber Orchestra for almost thirty years, he is now Conductor Laureate for Life. He was also Music Director of the Israel Chamber Orchestra and is now their Conductor Laureate. In the 2010-2011 season, Entremont became Principal Conductor of the Boca Raton Philharmonic, and Lifetime Laureate Conductor of the Munich Symphony Orchestra.

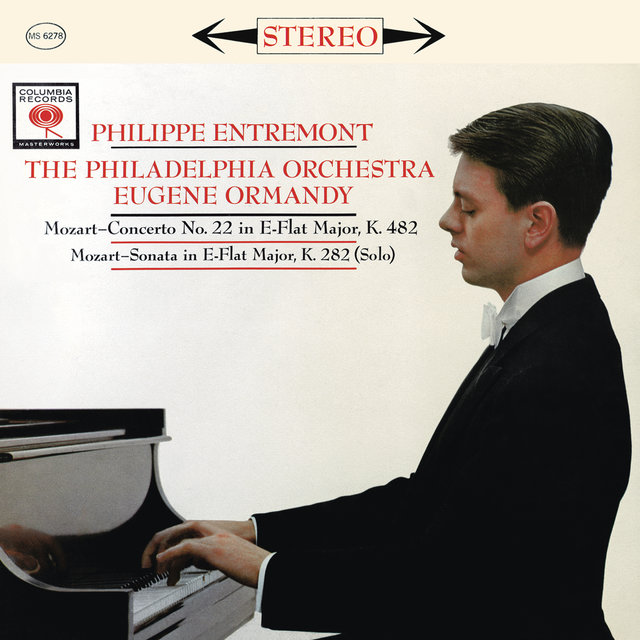

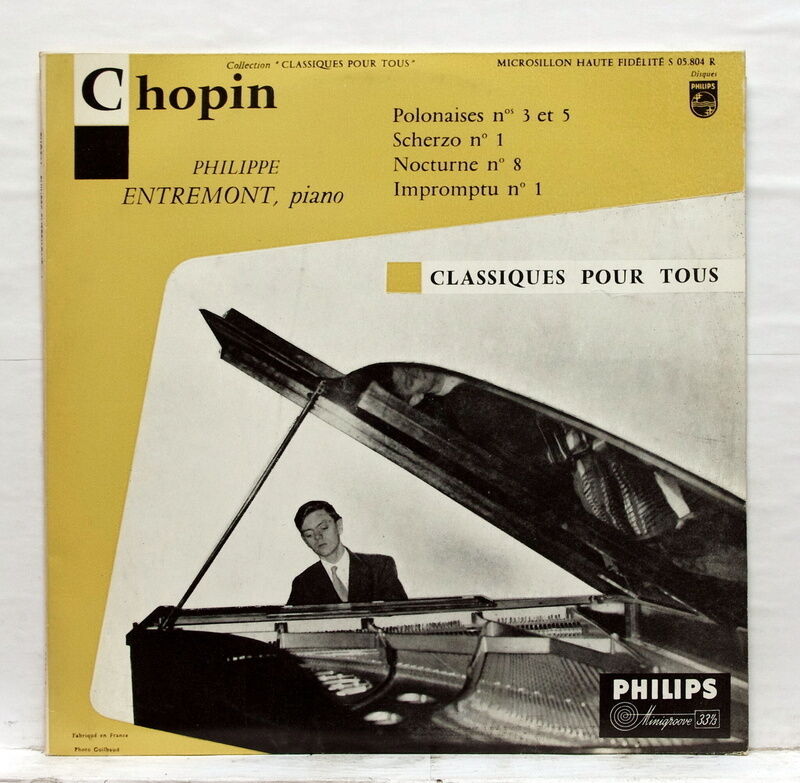

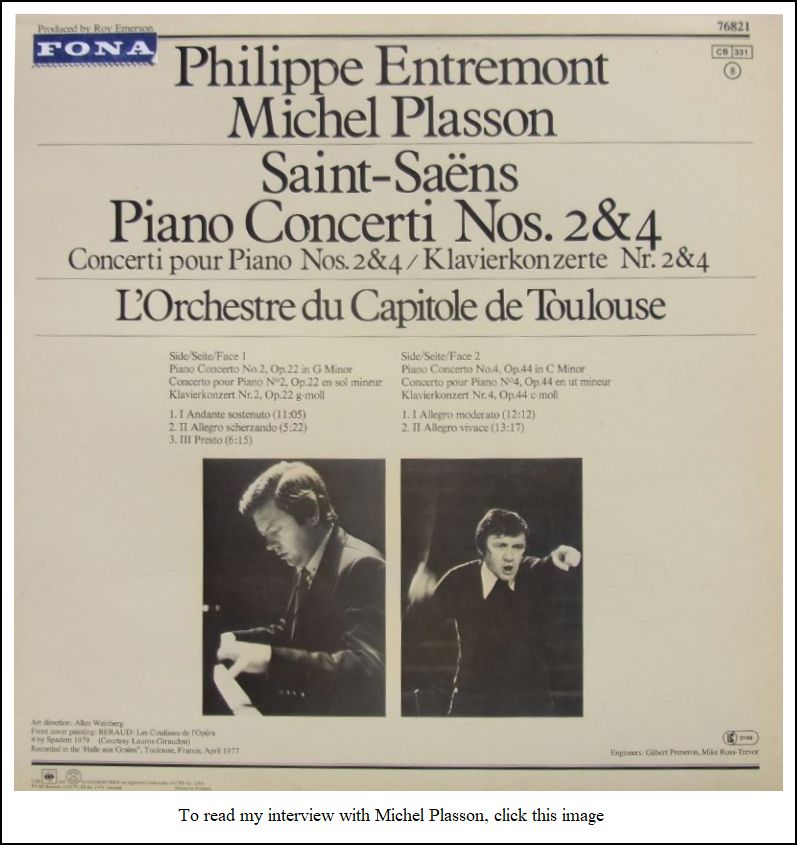

Entremont has directed the greatest symphony orchestras of Europe, Asia and America: Philadelphia, San Francisco, Detroit, Minnesota, Seattle, St. Louis, Houston, Dallas, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, Montreal, The Academy of Saint Martin in the Fields, The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, the Orquestra Nacional de España, the Academy of Santa Cecilia of Rome, l’Orchestre National de France, the orchestras of Göteberg, Stockholm, Oslo and Warsaw, the NHK of Tokyo, the KBS Orchestra of Seoul, the Vienna Symphony and the Philharmonic Orchestra of Bergen, to name a few. He has worked with the worlds greatest soloists, both instrumental and vocal. One of the most recorded artists of all time, Philippe Entremont has appeared on many labels, including CBS Sony, Teldec and Harmonia Mundi, and he has garnered all of the leading prizes and awards in the industry. In 2014, Sony issued a box of 19 CDs of all the piano concerti he played under the direction of Eugene Ormandy, Leonard Bernstein, and Charles Dutoit. Among his awards are the Great Cross of the Austrian Republic Order of Merit, Officer of the French Legion of Honor, Commander of the Order of Merit, Commander of the Order of Arts et Lettres, Philippe Entremont has also been awarded the Arts and Sciences Cross of Honor of Austria. He is President of the International Certificate for Piano Artists, President of the Bel’Arte Foundation of Brussels and is Director of the famed American Conservatory of Fountainebleau, a post formerly held by the legendary Nadia Boulanger. -- Biography (text only) excerpted from Columbia

Artists Website

-- Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

PE: If you start to think that it must be perfect, you

are in for big trouble. It dries out the performance. You

lack any spontaneity. It no longer artistry. Just the idea

of being perfect is awful. This is the only way to make wrong notes!

[Laughs] That’s it. You have to forget about it. You

have to forget about it, and to play the way you feel. Let me tell

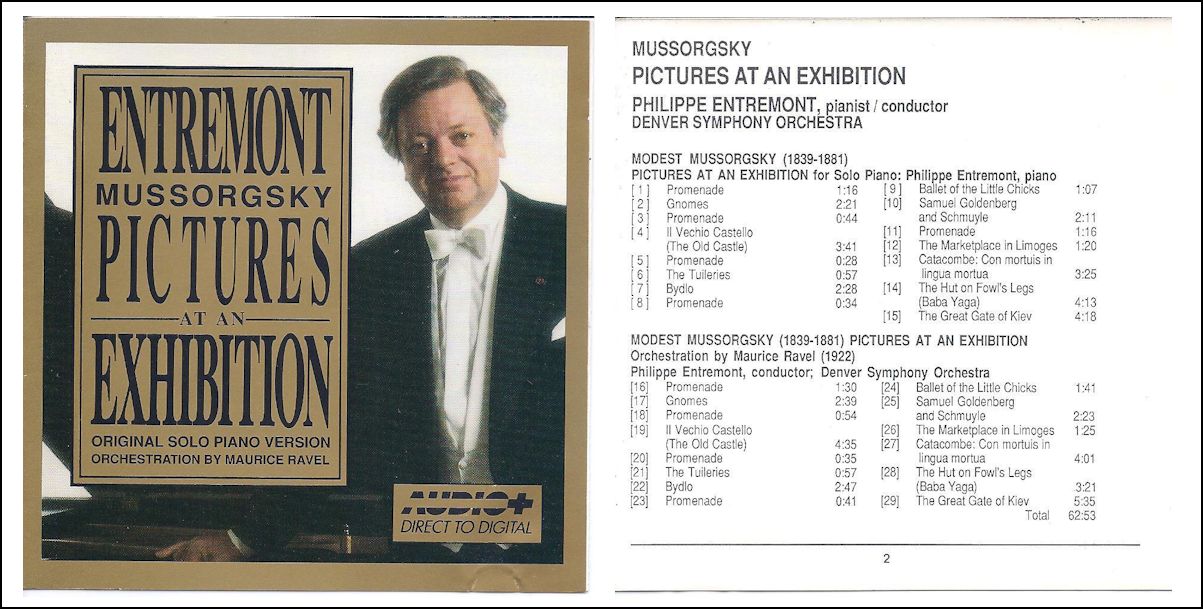

you about the latest ones I have done, all the Beethoven Piano Concertos.

It was amazing. It was not done bar by bar. At least half

of them were done in a complete take.

PE: If you start to think that it must be perfect, you

are in for big trouble. It dries out the performance. You

lack any spontaneity. It no longer artistry. Just the idea

of being perfect is awful. This is the only way to make wrong notes!

[Laughs] That’s it. You have to forget about it. You

have to forget about it, and to play the way you feel. Let me tell

you about the latest ones I have done, all the Beethoven Piano Concertos.

It was amazing. It was not done bar by bar. At least half

of them were done in a complete take. BD: Have you had the experience of conducting while

someone else is playing the piano?

BD: Have you had the experience of conducting while

someone else is playing the piano? PE: I make the choice myself.

I choose the piece I’m going to play, or the piece I’m going to conduct.

Sometimes people ask me if I am willing to direct it, and I am willing

or I am not.

PE: I make the choice myself.

I choose the piece I’m going to play, or the piece I’m going to conduct.

Sometimes people ask me if I am willing to direct it, and I am willing

or I am not. BD: Would that make you turn down another engagement

in Cleveland?

BD: Would that make you turn down another engagement

in Cleveland?| The four composers were Jeff Hamburg (born 1956 in Philadelphia, based in the Netherlands

since 1978); Joep Straesser (1934-2004), who wrote organ works and chamber

works for specialized ensembles; Hans Kox (1930- ), who has written a

wide range of instrumental and vocal music; and Robert Zuidam (1954- ),

who studied at Tanglewood with Lukas Foss and Oliver Knussen, and

won a Koussevitzky composition prize, and was a visiting professor at Harvard. |

BD: Where is music going today?

BD: Where is music going today? PE: To play the harpsichord is completely different from

playing the piano. First of all, the keys are smaller, and you

have to adjust yourself to the spread of your hand as well. It’s

difficult. I have played the harpsichord myself, not only for

fun but in concerts. The first time I played the harpsichord was

at the Vienna Festival, with the Brandenburg No. 5, and you know

how difficult the harpsichord part is. I practiced the harpsichord

like crazy for three months.

PE: To play the harpsichord is completely different from

playing the piano. First of all, the keys are smaller, and you

have to adjust yourself to the spread of your hand as well. It’s

difficult. I have played the harpsichord myself, not only for

fun but in concerts. The first time I played the harpsichord was

at the Vienna Festival, with the Brandenburg No. 5, and you know

how difficult the harpsichord part is. I practiced the harpsichord

like crazy for three months. BD: But when you’ve judged them, what do you look for?

BD: But when you’ve judged them, what do you look for? BD: You say you’re so busy.

Do you allow yourself enough time for rest, and for family, and to

learn new repertoire?

BD: You say you’re so busy.

Do you allow yourself enough time for rest, and for family, and to

learn new repertoire?

© 1997 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on October 15, 1997. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1999. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.