In December 2015 Till Fellner will make his debut with the Berlin Philharmonic,

under the baton of Bernard

Haitink, performing Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 25 in C major. Other highlights

of the 2015-16 season include recitals in major halls in Europe and Asia

as well as concerts with the NHK Symphony Orchestra/Herbert Blomstedt,

Chicago Symphony Orchestra/Bernard Haitink, the Academy of St Martin in the

Fields/Sir Neville Marriner, and the Mahler Chamber Orchestra/Manfred Honeck.

In December 2015 Till Fellner will make his debut with the Berlin Philharmonic,

under the baton of Bernard

Haitink, performing Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 25 in C major. Other highlights

of the 2015-16 season include recitals in major halls in Europe and Asia

as well as concerts with the NHK Symphony Orchestra/Herbert Blomstedt,

Chicago Symphony Orchestra/Bernard Haitink, the Academy of St Martin in the

Fields/Sir Neville Marriner, and the Mahler Chamber Orchestra/Manfred Honeck.Till Fellner has collaborated with Claudio Abbado, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Semyon Bychkov, Christoph von Dohnányi, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Sir Charles Mackerras, Kurt Masur, Kent Nagano, Jonathan Nott, Kirill Petrenko, Claudius Traunfellner, and Hans Zender, among many others.

In the field of chamber music Till Fellner regularly collaborates with the British tenor Mark Padmore, with whom he will give the first performance of a composition by Hans Zender in January 2016. They will also perform lieder recitals in Germany, Tokyo and Seoul. The Belcea Quartet has invited him to celebrate their 20th anniversary in 2015 with performances of Brahms’ Piano Quintet in major cities throughout Europe and a subsequent recording.

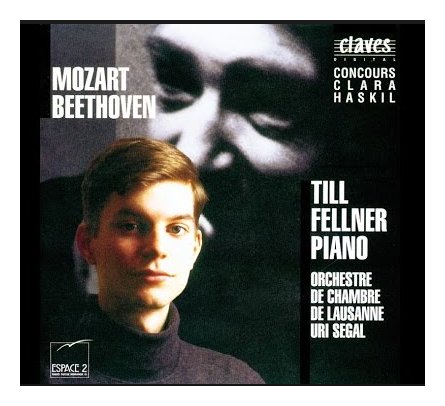

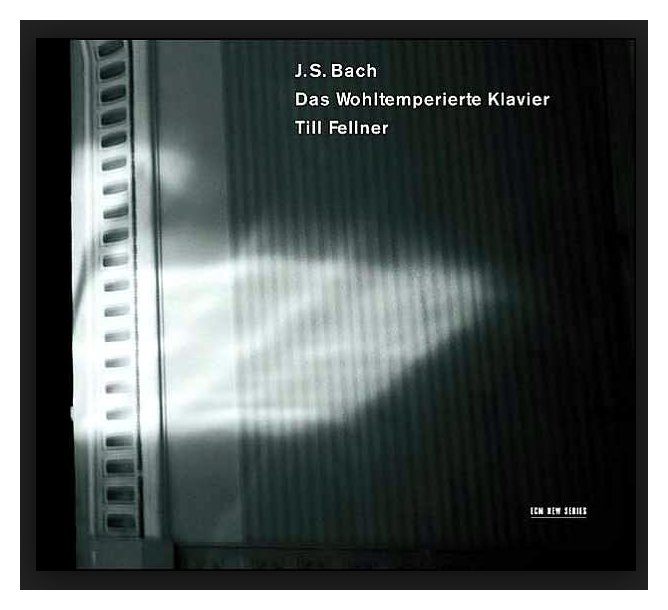

Over the past few years he has dedicated himself to two milestones of the piano repertoire: the Well-Tempered Clavier of Johann Sebastian Bach and the 32 piano sonatas of Ludwig van Beethoven. He performed the Beethoven cycle from 2008 to 2010 in New York, Washington, Tokyo, London, Paris and Vienna. Furthermore contemporary music is of great importance to him; he has given the world premieres of works by Kit Armstrong, Harrison Birtwistle, Thomas Larcher, and Alexander Stankovski. In 2012 Till Fellner withdrew from performing for a year to devote himself to the study of new repertoire and to deepen his knowledge of composition, literature and film.

The ECM label, for whom Till Fellner is an exclusive recording artist, has released the First Book of the Well-Tempered Clavier and the Two & Three-Part Inventions of J. S. Bach, Beethoven’s Piano Concertos Nos. 4 & 5 with the Montreal Symphony Orchestra and Kent Nagano and, most recently, a CD of chamber music by Harrison Birtwistle.

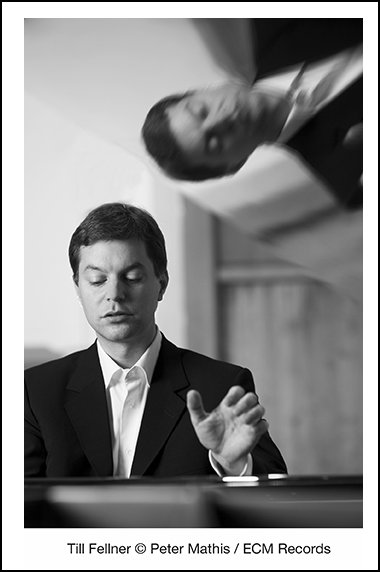

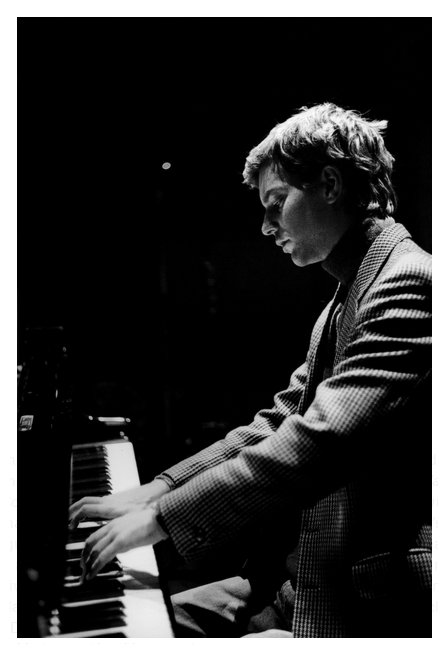

In his native Vienna, Till Fellner studied with Helene Sedo-Stadler before going on to study privately with Alfred Brendel, Meira Farkas, Oleg Maisenberg, and Claus-Christian Schuster.

Since autumn 2013, Till Fellner has been engaged to teach a small circle of students at the Zurich Hochschule der Künste.

-- Biography from the artist’s

website

-- Names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

-- Names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

BD

BD TF

TF TF

TF BD

BD

BD

BD