|

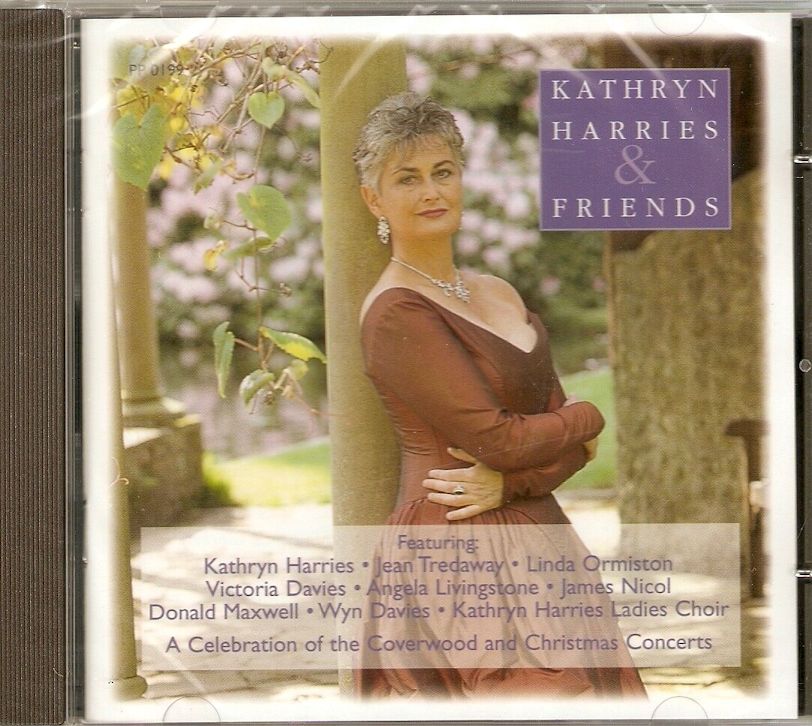

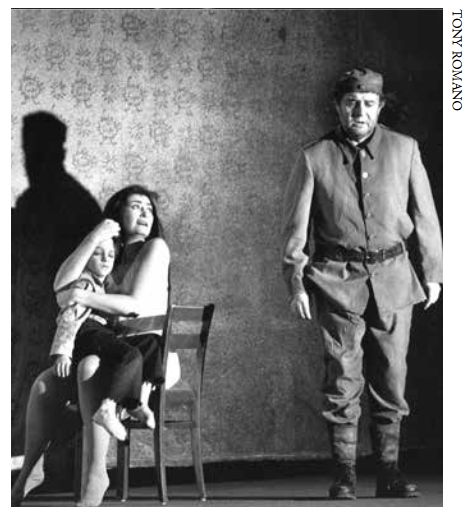

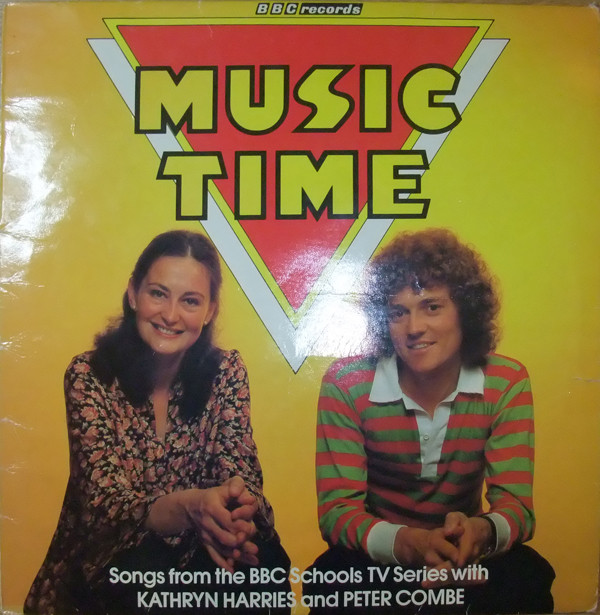

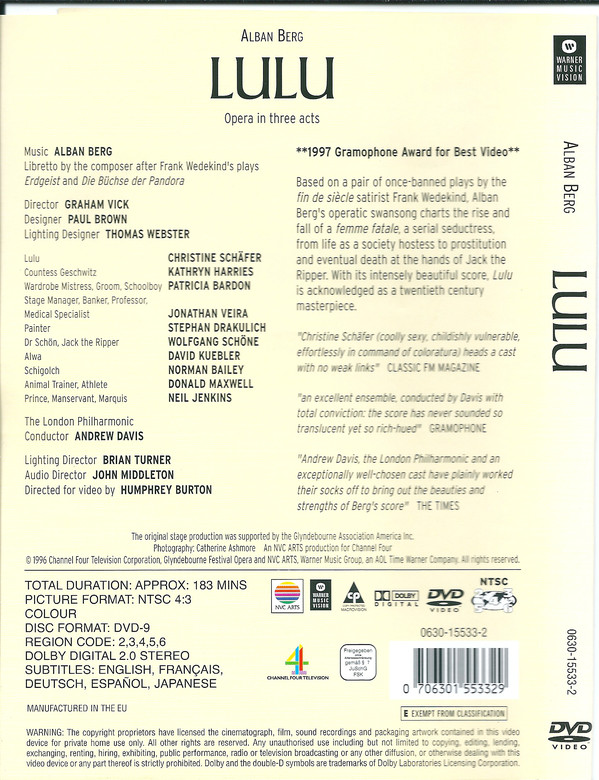

After studying for five years at the Royal Academy of Music and London University, in 1974 Kathryn Harries embarked upon a successful solo career as a recitalist and concert artist. Between 1977 and 1983 she presented the award-winning program Music Time for BBC One Television, and made her operatic debut in 1983 at Welsh National Opera as a Flower Maiden in Parsifal and as Leonore in Fidelio. Her repertoire comprises more than sixty roles including Kostelnička (Jenůfa), Kundry (Parsifal), Sieglinde (The Valkyrie), Gutrune, (Götterdämerung), Brangäne (Tristan und Isolde), Emilia Marty (Die Sache Makropulos), Didon (Les Troyens), Marie (Wozzeck), Carmen (Carmen), Judith (Bluebeard’s Castle), Donna Elvira (Don Giovanni), and Countess Geschwitz (Lulu). She has performed at all the leading British opera venues

including the Royal Opera House, English National Opera, the Edinburgh

Festival, and Glyndebourne Festival, as well as at major houses in the

USA (Metropolitan Opera, New York City Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, San

Francisco Opera and Los Angeles), and in Europe (the Palais Garnier, Chatelet

and Bastille, Paris; Lyons; St. Etienne; Orange; Hamburg; Stuttgart; Berlin;

Amsterdam; Genoa; Rome; Bilbao; Oviedo; Liège; Salzburg; Bochum.).

Harries is highly active as a concert singer, performing with the English Northern Philharmonia, the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the Barbican, as well as in The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny at the BBC Proms, in Bremen and Lucerne with the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra. Among performances of the recent past are Kostelnička (Jenůfa), Mrs. Sedley (Peter Grimes), Massenet's Herodiade, Kabanicha (Katya Kabanova), Valerie von Kant (The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant), Stolzius's Mother (Die Soldaten), Mrs. Grose (The Turn of the Screw), the Old Lady (Candide) and Emilia Marty (The Makropoulos Case). Kathryn Harries was appointed Director of the National Opera Studio in London in 2009 and she is gaining an international reputation as a voice teacher and coach. She is vocal consultant for the new NI Opera in Northern Ireland and she regularly gives master classes in the UK and abroad. Kathryn was appointed senior judge for the Lexus Song Quest in New Zealand in 2014 and recently returned from Auckland, where she was chief vocal coach for the inaugural Kiri Programme. Kathryn has been a supporter of a wide variety of charities

since 1977 and she has organised and sung at hundreds of concerts, raising

over £400,000. Kathryn is also a keen long-distance walker and, in

2001, she walked from John O’Groats to Land’s End for Speakability, raising

£86,000. In 2006, she created the Opera Walk to raise funds for the

ENO and WNO Benevolent Funds and walked from London to Cardiff, Cardiff to

Leeds and then back to London. Her annual walk takes place in London for

the charity, Cardiac Risk in the Young (CRY).

== Adapted from the biography on the Opera

Prelude website

|

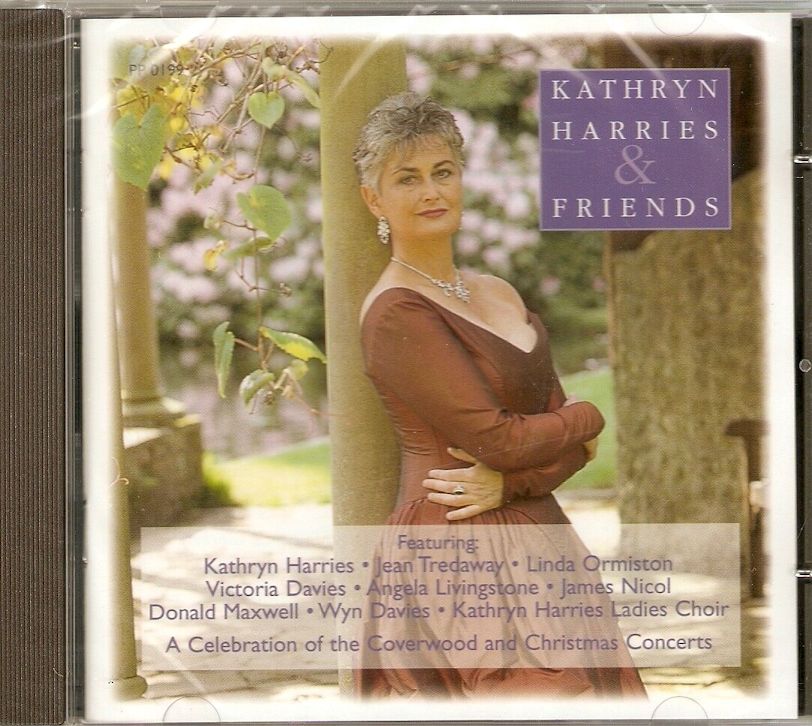

I had the chance to speak with Kathryn Harries during her

first visit to Chicago early in 1994, for Marie in Wozzeck [shown

in photo at right, with Franz Grundheber in the title role, and Thomas Edward

McGunn as their son]. We talked of her roles, her life, and the

advice she had for both professionals and audiences.

I had the chance to speak with Kathryn Harries during her

first visit to Chicago early in 1994, for Marie in Wozzeck [shown

in photo at right, with Franz Grundheber in the title role, and Thomas Edward

McGunn as their son]. We talked of her roles, her life, and the

advice she had for both professionals and audiences.

Harries: I studied as a singer and as a pianist, and did

a teacher’s course at the Royal Academy of Music, and earned my living teaching

piano and singing. I taught lots and lots of little children.

It was great fun, and I loved it. Subsequently, I did a television

program on the BBC, teaching music for children, and I’ve often thought all

that teaching was really performing. It’s all about communicating.

Now being on the stage is just a different version of the same thing.

Harries: I studied as a singer and as a pianist, and did

a teacher’s course at the Royal Academy of Music, and earned my living teaching

piano and singing. I taught lots and lots of little children.

It was great fun, and I loved it. Subsequently, I did a television

program on the BBC, teaching music for children, and I’ve often thought all

that teaching was really performing. It’s all about communicating.

Now being on the stage is just a different version of the same thing.Kathryn Harries at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1993-94 Wozzeck (Marie) with Grundheber,

Kaasch, Clark, Bailey, Svendén;

R. Buckley,

Alden, Schuler, Palumbo

1996-97 Un Re in Ascolto [Berio] (Protagonist) with Lafont, Desderi, Woods, Begley; Davies, Vick, Tallchief 2000-01 Jenůfa (Kostelnička) with Racette, Smith, Denniston; Davis, Jones 2004-05 A Wedding [Bolcom] (Nettie and Aunt Bea) with Malfitano, Hadley, Gardner, Doss, Flannigan, Lawrence, Cangelosi; Davies, Altman |

BD: It’s 3,600 seats, and the Met has 4,000.

BD: It’s 3,600 seats, and the Met has 4,000.This conversation was recorded in Chicago on February 7, 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 2000. This transcription was made in 1996, and published in The Opera Journal in March of that year. In 2020 it was slightlly re-edited, the photos and boxes were added, and it was posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.