|

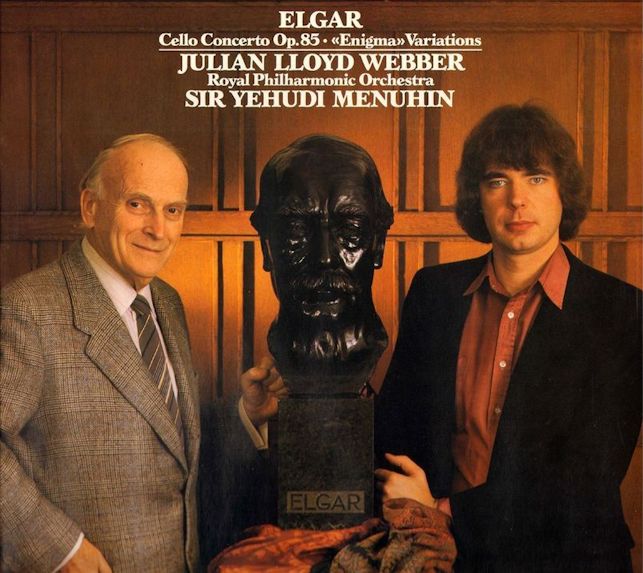

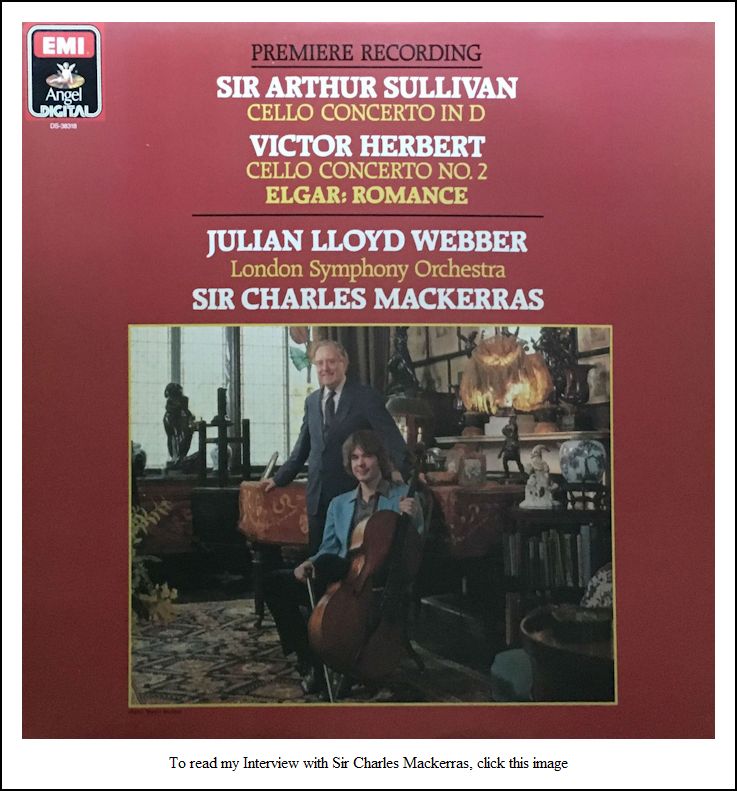

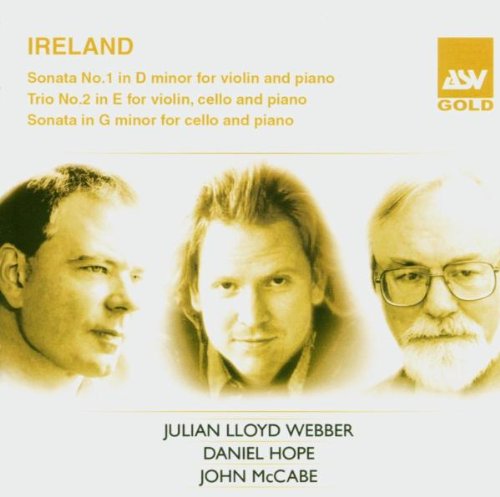

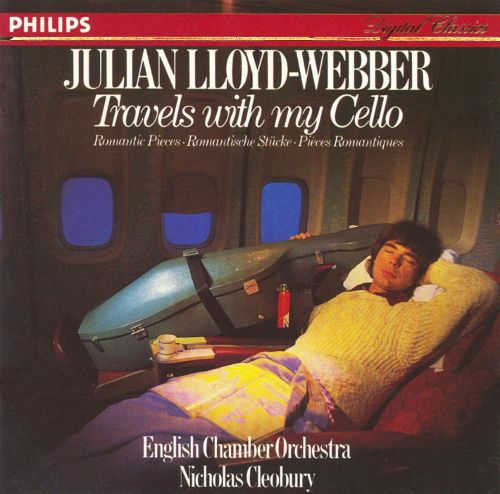

Julian Lloyd Webber (born April 14, 1951) is the second son of the composer William Lloyd Webber and his wife Jean Johnstone (a piano teacher). He is the younger brother of the composer Andrew Lloyd Webber. The composer Herbert Howells was his godfather. Lloyd Webber was educated at three schools in London: at Wetherby School, a pre-prep school in South Kensington, followed by Westminster Under School and University College School. He then won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music and completed his studies with Pierre Fournier in Geneva in 1973. Lloyd Webber made his professional debut at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, in September 1972 when he gave the first London performance of the Cello Concerto by Sir Arthur Bliss. Throughout his career, he has collaborated with a wide variety of musicians, including Yehudi Menuhin, Lorin Maazel, Neville Marriner, Georg Solti, Yevgeny Svetlanov, Andrew Davis and Esa-Pekka Salonen as well as Stéphane Grappelli, Elton John and Cleo Laine. He was described in The Strad as the "doyen of British cellists". His many recordings include his BRIT Award winning Elgar Cello

Concerto conducted by Menuhin (chosen as the finest ever version by

BBC Music Magazine), the Dvořák Cello Concerto with Václav

Neumann and the Czech Philharmonic, Tchaikovsky's Rococo Variations

with the London Symphony Orchestra under Maxim Shostakovich

and a coupling of Britten's Cello Symphony and Walton's Cello

Concerto with Sir Neville Marriner and the Academy of St Martin in the

Fields. Several CDs are of short pieces for Universal Classics including

Made in England, Cello Moods, Cradle Song

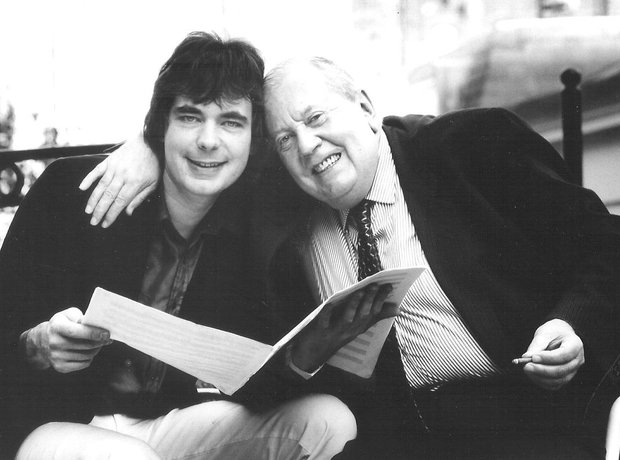

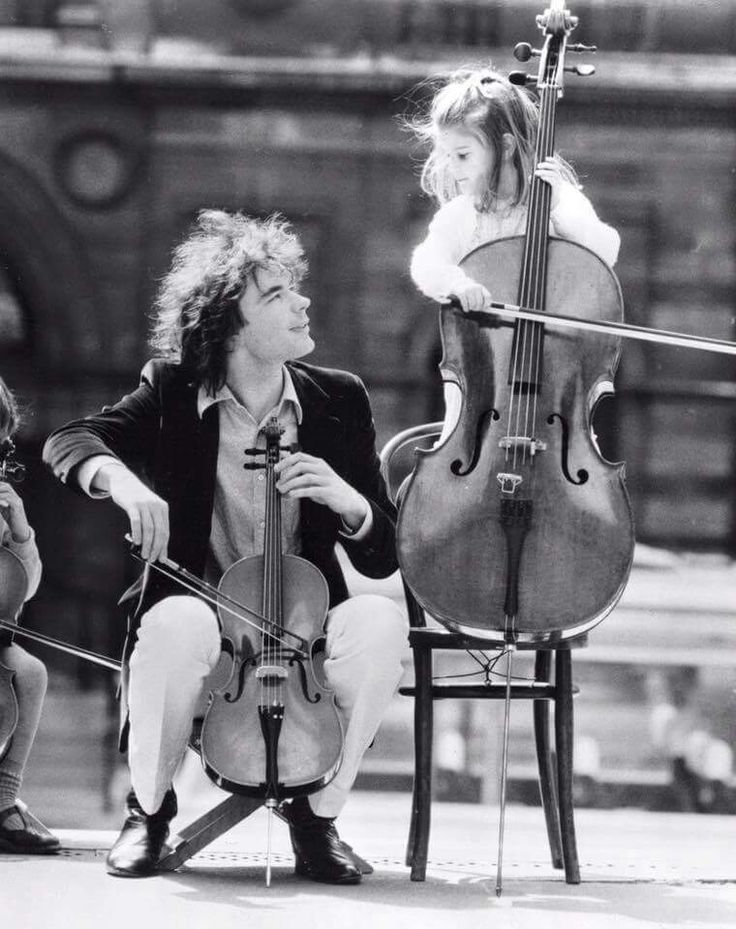

and English Idyll. Lloyd Webber premiered the recordings of more than 50 works, inspiring new compositions for cello from composers as diverse as Malcolm Arnold (Fantasy for Cello, 1986, and Cello Concerto, 1989), Joaquín Rodrigo (Concierto como un divertimento, 1982) James MacMillan (Cello Sonata No. 2, 2001), and Philip Glass (Cello Concerto, 2001). More recent concert performances have included four further works composed for Lloyd Webber – Michael Nyman's Double Concerto for Cello and Saxophone on BBC Television, Gavin Bryars's Concerto in Suntory Hall, Tokyo, Philip Glass's Cello Concerto at the Beijing International Festival and Eric Whitacre's The River Cam at the Southbank Centre. His recording of the Glass Concerto with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic conducted by Gerard Schwarz was released on Glass' Orange Mountain label in September 2005. Recent recordings include his debut recording as a conductor of English music for strings 'And the Bridge is Love' (2015). In May 2001, he was granted the first busker's licence on the London Underground. Demonstrating his involvement in music education, he formed the "Music Education Consortium" with James Galway and Evelyn Glennie in 2003. As a result of successful lobbying by the Consortium, on 21 November 2007, the UK government announced an infusion of £332 million for music education. In 2008, the British Government invited Lloyd Webber to be Chairman of its In Harmony programme which is based on the Venezuelan social programme El Sistema. The government-commissioned Henley Review of Music Education (2011) reported, "There is no doubt that they (the in Harmony projects) have delivered life-changing experiences." In July 2011 the founder of El Sistema in Venezuela, José Antonio Abreu, recognised In Harmony as part of the El Sistema worldwide network. Further, in November 2011 the British government announced additional support for In Harmony across England by extending funding from the Department for Education and adding funding from Arts Council England from 2012 to 2015. Lloyd Webber now chairs the charity Sistema England. In October 2012 he led the Incorporated Society of Musicians campaign against the implementation of the EBacc which proposed to remove Arts subjects from the core curriculum. In February 2013 the Government withdrew its plans. Lloyd Webber has represented the music education sector on programmes such as BBC1's Question Time, The Andrew Marr Show, BBC2's Newsnight and BBC Radio 4's Today, The World at One, PM, Front Row and The World Tonight. In May 2009, Lloyd Webber was elected President of the Elgar Society in succession to Sir Adrian Boult, Lord Menuhin, and Richard Hickox. In April 2014, Lloyd Webber was awarded the Incorporated Society of Musicians' Distinguished Musician Award (DMA) at their annual conference. In September 2014, the charity Live Music Now announced Lloyd Webber as its next public spokesman. On 28 April 2014, he announced his retirement from public performance as a cellist because of a herniated disc in his neck. His final public performance as a cellist was on 2 May 2014 at the Festival Theatre, Malvern with the English Chamber Orchestra when he played the Barjansky Stradivarius cello (dated c. 1690) which he had played for more than thirty years. In March 2015, he was announced as principal of the Birmingham Conservatoire. Lloyd Webber received the Crystal Award at the World Economic Forum in 1998 and a Classic FM Red Award for outstanding services to music in 2005. He won the 'Best British Classical Recording' in 1986 at the Brit Awards for his recording of Cello Concerto (Elgar) with Sir Yehudi Menuhin and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. He was made a Fellow of the Royal College of Music in 1994 and has received honorary doctorates from the University of Hull, Plymouth University and Thames Valley University. He is vice president of the Delius Society and patron of Music in

Hospitals. He has been an ambassador for the Prince's Trust for more than

twenty years [photo below shows Lloyd Webber with HRH Charles] and

a patron of CLIC Sargent for more than 30 years.

In September 2009 he joined the board of governors of the Southbank Centre. He was the Foundling Museum's Handel Fellow for 2010. He was the only classical musician chosen to play at the Closing Ceremony of Olympics 2012. On 16 April 2014 Lloyd Webber received the Incorporated Society of

Musicians Distinguished Musician Award. -- Note: Names which are links refer to my

Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

BD: It’s not that they’re not interested,

are they?

BD: It’s not that they’re not interested,

are they?  BD: It was just ground up sounds

and noises?

BD: It was just ground up sounds

and noises? BD: Is there some vocalism that works with this?

Can you bring a singing tone to a purely instrumental sound?

BD: Is there some vocalism that works with this?

Can you bring a singing tone to a purely instrumental sound?  BD: Quartets are balanced well, but it seems like the

cellist gets a bit lost in trios.

BD: Quartets are balanced well, but it seems like the

cellist gets a bit lost in trios. BD: In the end, though, is it all

worth it?

BD: In the end, though, is it all

worth it?  BD: Is it then very special to play those two pieces

on that cello?

BD: Is it then very special to play those two pieces

on that cello?  BD:

Would it give you a good feeling to be taken up by others?

BD:

Would it give you a good feeling to be taken up by others?

© 1995 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Lake Forest, Illinois, on November 16, 1995. Portions were broadcast on WNIB three months later. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.