| Wilfred Josephs

was born in Newcastle on July 24, 1927 and educated at Rutherford School

before his early schooling and piano studies were interrupted by wartime

evacuation. Although persuaded by his family to enroll as a medical student,

he was still able to receive musical tuition from Dr. Arthur Milner. It

was as a dentist that he spent his military service. His early obsession

with composition was soon vindicated when he won a Gaudeamus Prize with

a Piano Trio during this period. He continued his studies on his

return to London, where a scholarship enabled him to become a pupil of Alfred

Nieman at the Guildhall School of Music. A Leverhulme Scholarship took

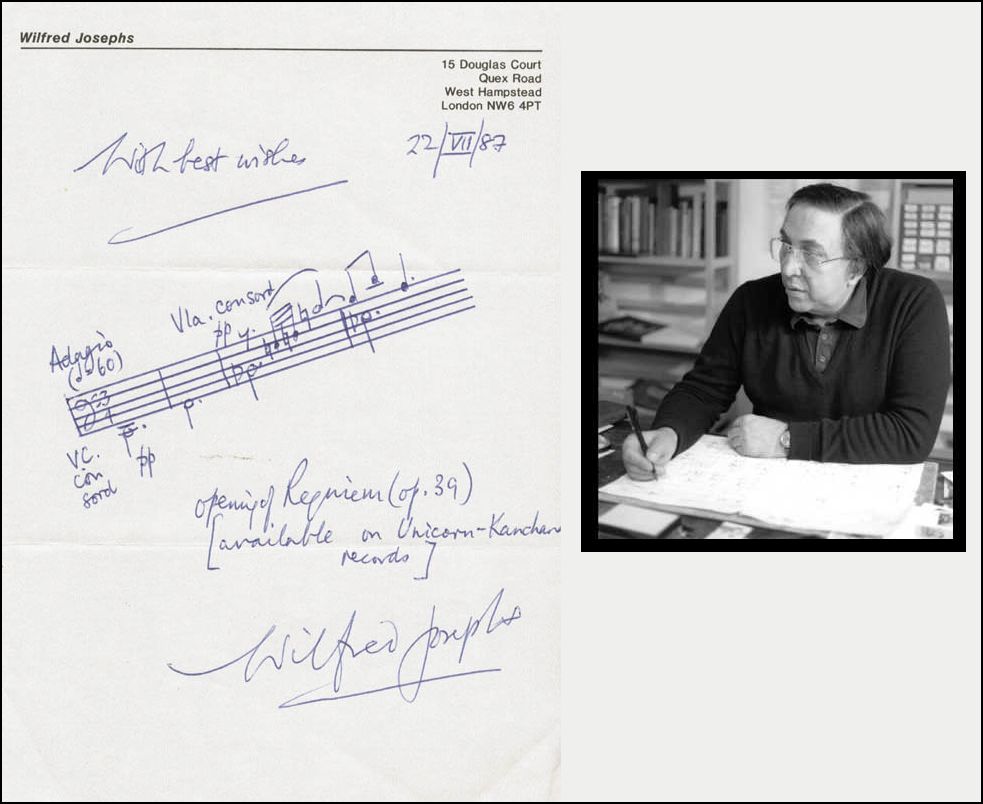

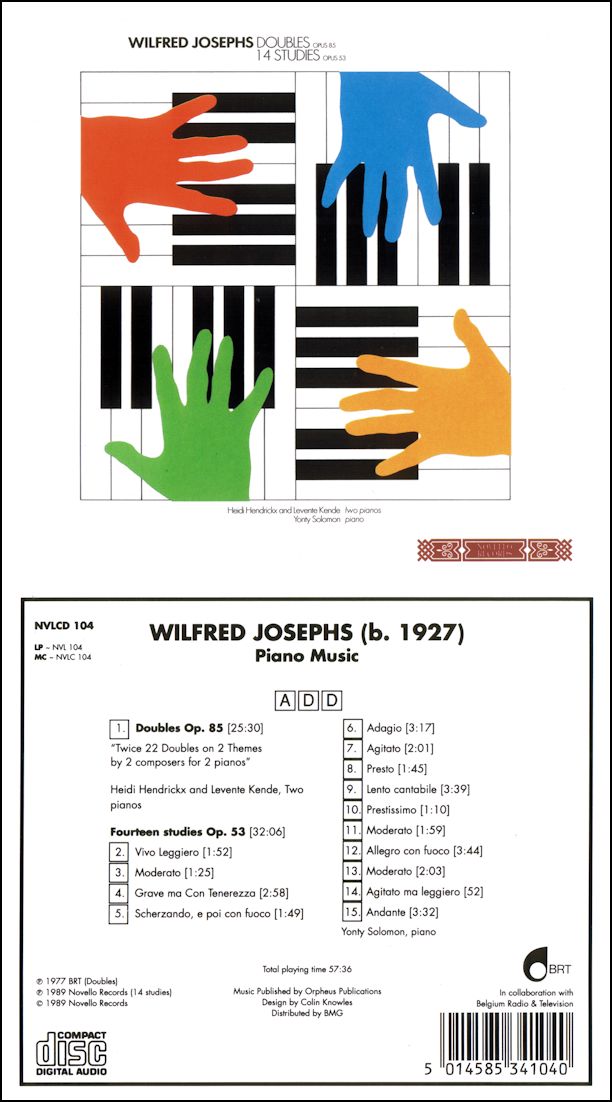

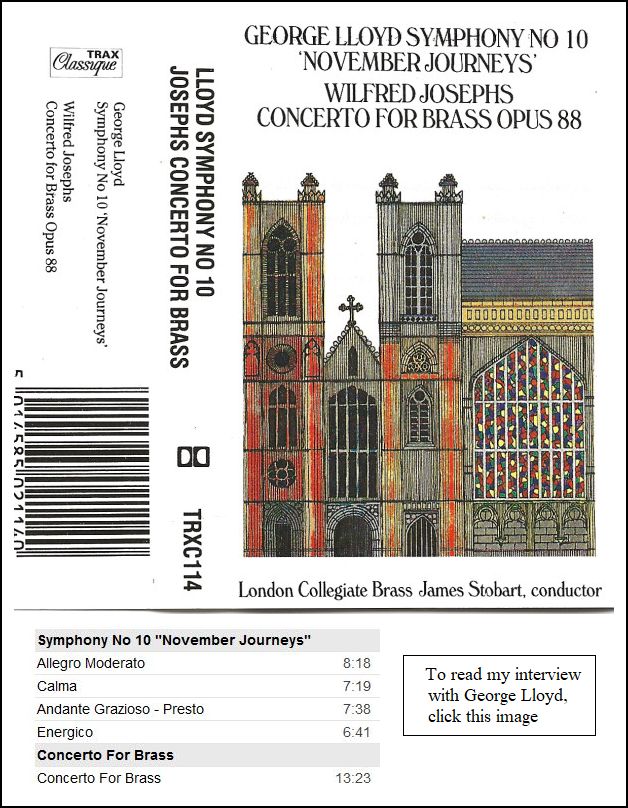

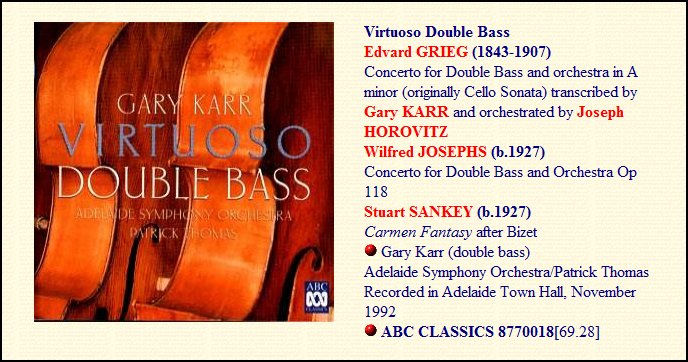

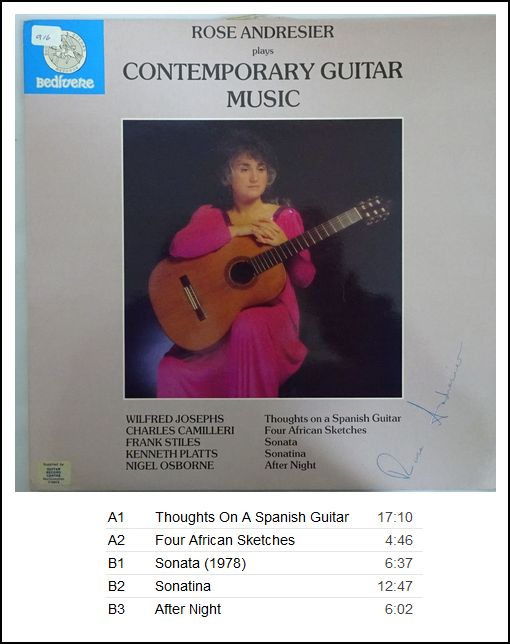

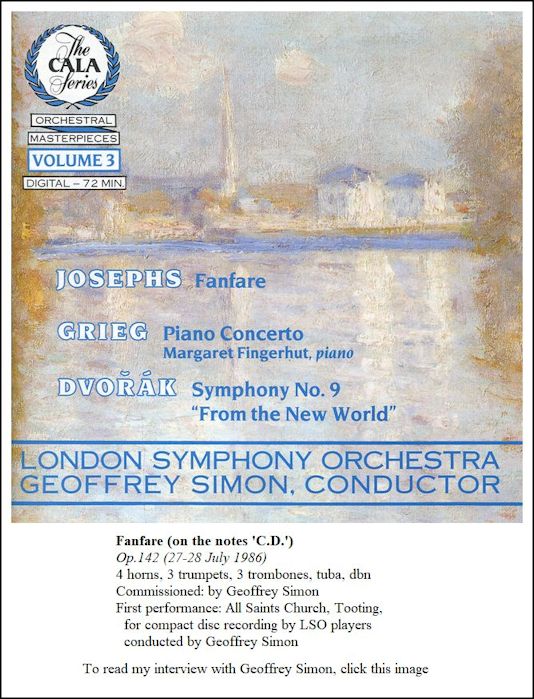

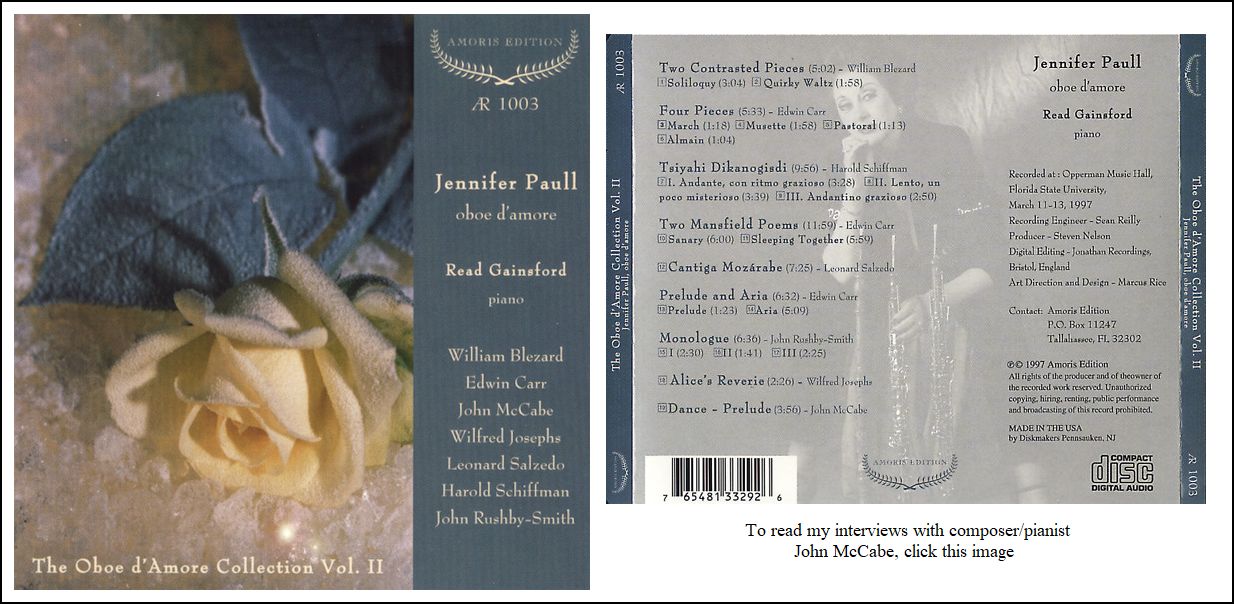

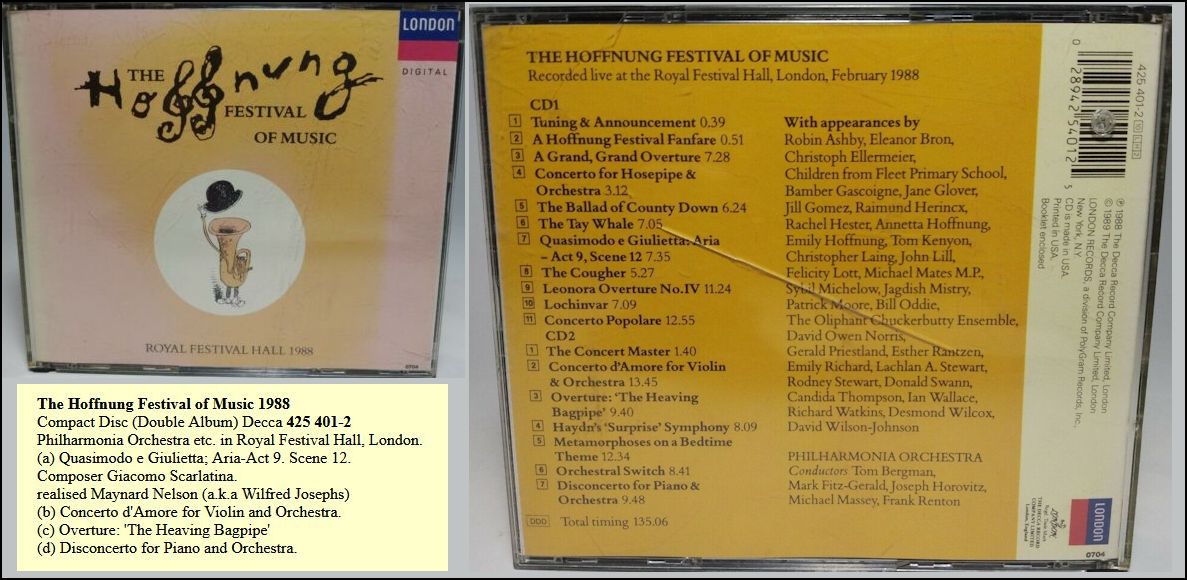

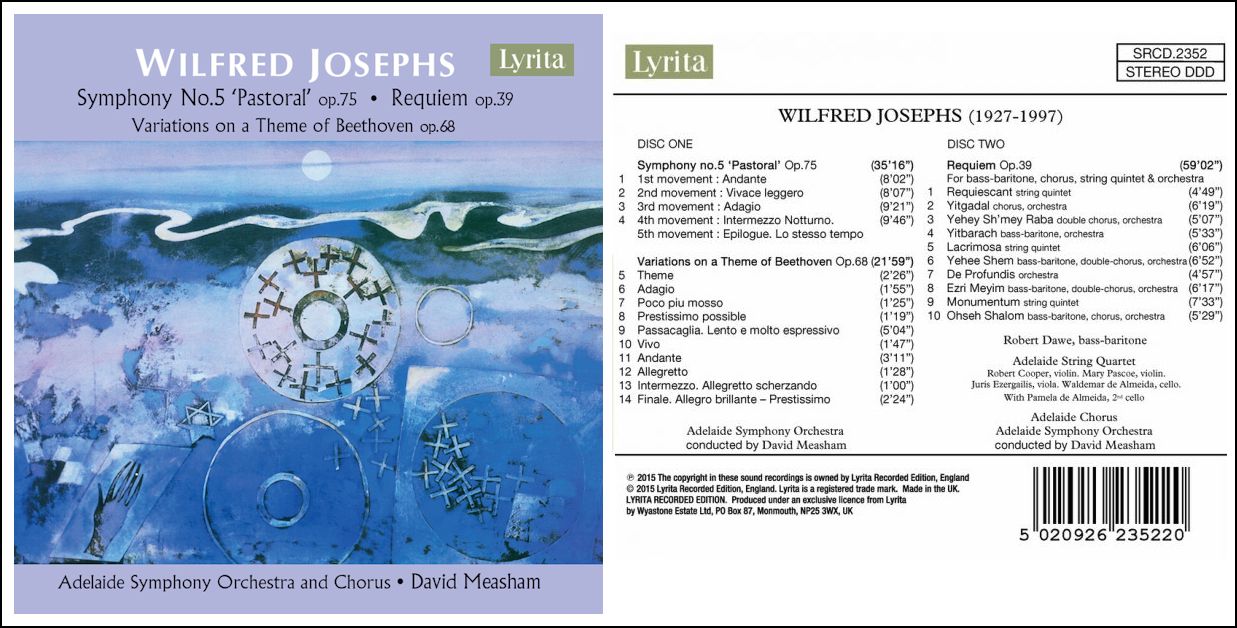

him to Paris for a year with Max Deutsch. A growing reputation, based on the success of his burgeoning catalogue of works, made it possible for Josephs to eventually devote all his time to music. Amongst the many prizes and awards won at this time was first prize for the First International Composition Competition of La Scala and the City of Milan, and the Harriet Cohen Commonwealth Medal. Josephs' music showed a recognizable personality from the start. Whilst his works dating from the beginning of the 1950's clearly had their roots in an earlier English style and tradition, lessons with Max Deutsch (a distinguished Schoenburg pupil) were to help him to assimilate the lessons of the Second Viennese School. Other stylistic explorations further diversified his range. In the gradual shift of contemporary music back to practices once regarded as seditious - the expressive use of tonal harmony, and particularly the writing of real tunes - it was inevitable that Josephs' outstanding natural gift should have found himself consistently in the vanguard. A prolific composer who nearly always wrote to commission, Josephs' concert works include 12 symphonies, 22 concertos, overtures, chamber music, operas, ballets and numerous vocal works. Opera North commissioned and performed Rebecca at the Grand Theatre, Leeds in 1983. The libretto for this acclaimed opera was by Edward Marsh, from the novel by Daphne du Maurier. Other important works in Wilfred Josephs' catalogue include Symphony 4 (1967), Symphony 5 "Pastoral" (1971), Symphony 10 "Circadian Rhythms" (1985), Nightmusic (1969) and Songs of Innocence (1971). To the impressive list of concert works must also be added his enormously successful scores for film and television, including The Great War, I Claudius, Swallows and Amazons, Cider with Rosie, This British Empire and All Creatures Great and Small. Wilfred Josephs died at his home in London on November 17th 1997. == Biography from Wise Music Classical website

|

What follows is an article by Bernard Jacobson,

posted on Music Web International on June 9, 2009.

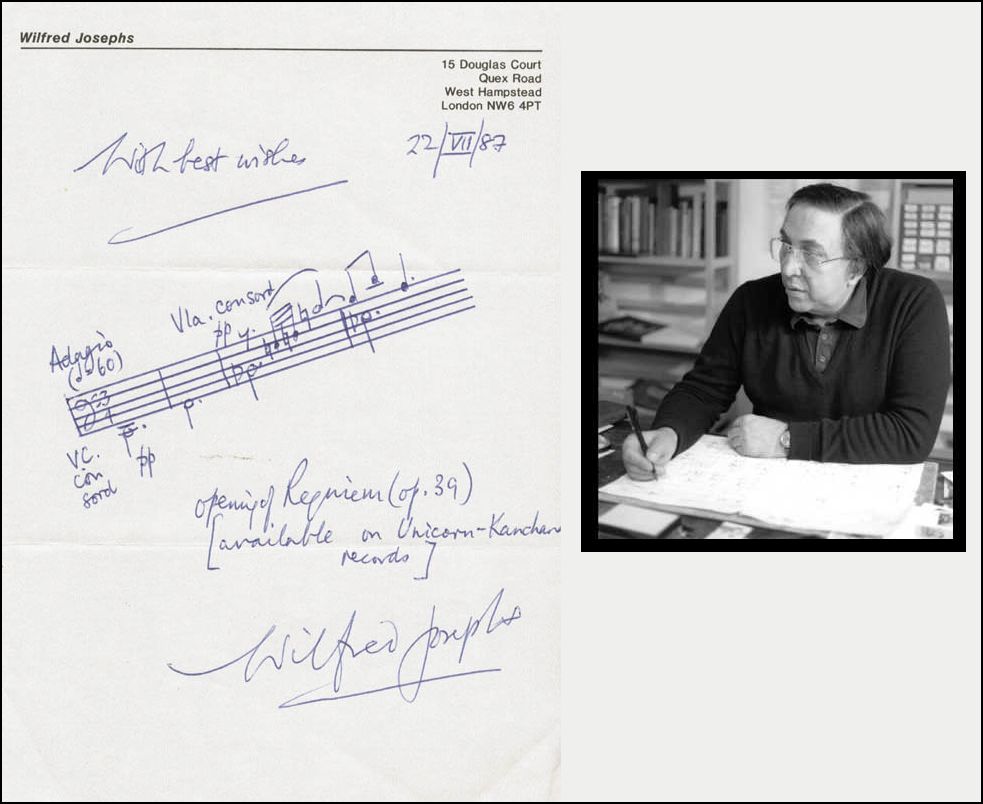

From a vantage point nearly half a century later, it could almost be called the breakthrough that wasn't. Very early one morning in December 1963, my friend Wilfred Josephs was awakened by a telephone call congratulating “Joseph Wilfred” on winning the First International Competition for Symphonic Composition of the City of Milan and La Scala. A jury chaired by Victor de Sabata, and including the composers Ghedini and Petrassi and the conductors Franco Ferrara and Nino Sanzogno, had declared his Requiem, completed nine months earlier, the winner. As part of the prize, the work had its premiere at La Scala on October 28 and 29, 1965, under Sanzogno's direction. Performances in the northern English cities of Sheffield and Leeds followed a year later, and in London, Paris, and Rotterdam within the next few seasons. Meanwhile Max Rudolf introduced the Requiem to the United States with a series of performances in Cincinnati and New York in January 1967, and in 1972, paired on a program with Mozart's 40th Symphony, it was given three times by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Carlo Maria Giulini, who dubbed it “the most important work by a living composer.” It was possible to feel over the next few years-and indeed I declared in print-that these successes had transformed Josephs' life and career. Born in Newcastle upon Tyne on July 24, 1927, he had begun his musical studies, part time, under Arthur Milner, qualifying as a dentist at the same time. A scholarship in 1954 to study with Alfred Nieman at the Guildhall School of Music in London, and a further year in 1958 under Max Deutsch in Paris financed by a Leverhulme Scholarship, helped to put the seal of professionalism on his work as a composer, but left him still with the need to earn a living through the practice of dentistry. After Milan he was able to devote himself entirely to composing, stimulated rather than distracted on a couple of occasions by the experience of teaching when his growing reputation in the United States brought him professorial posts at universities in Milwaukee and Chicago. By the time of his death in 1997 his works, written by then almost exclusively on commission, numbered nearly 200. They include twelve symphonies, more than a dozen concertos, several large-scale ballets, a ground-breaking piece of music theater written in collaboration with the playwright Arnold Wesker and titled The Nottingham Captain, and an opera, Rebecca, composed for Opera North in England and premiered before packed houses in 1983. Bearing the opus number 39, the Requiem represents Josephs at a crucial stage in his long and fruitful stylistic development. Max Deutsch (who was himself to conduct the French premiere of the work in Paris in 1970) was a distinguished Schoenberg pupil. His teaching had clearly helped the young composer to assimilate the lessons of the Second Viennese School and to come out, as it were, on the other side. Josephs was indeed one of the first to realize (as a growing number of composers of impeccable “avant-garde” credentials came to feel) that, with Schoenberg's “emancipation of the dissonance” long since achieved, there was no further need to exclude tonal structures from music as if they were potential sources of some kind of infection. The Requiem makes free play with tonal implications. They are used, however, for purely expressive purposes, while the formal organization of the work is based on techniques stemming essentially from the 12-tone method but no longer narrowly 12-tone in character. In other words (rather like his older contemporary Andrzej Panufnik, whom he greatly admired), Josephs develops his material through the horizontal and vertical elaboration of basic sets, but the sets no longer obey the a priori rules of 12-tone serialism. They tend to be much shorter and less exclusively chromatic, and their flavor-founded here on the intervals of the perfect fourth, the augmented fourth, the semitone, and the major second-points firmly forward to the real tunes Josephs in his later music increasingly reasserted the right to create. The origins of this non-Latin Requiem go back to the arrest and trial of Adolf Eichmann in the late 1950s, and in a profounder sense they go back still farther than that. The Eichmann trial reawakened Josephs' horror at the sufferings of Jews during the Second World War. In memory of those who died, he wrote a String Quintet, which consisted of three slow movements and originally bore the title Requiescant. It was composed between February and June 1961. Later, feeling that he had more to say on the subject, he conceived the idea of incorporating the Quintet in a choral work, which would be a setting of the Kaddish traditionally recited by Jewish mourners for their dead as part of the liturgy. The choice of text, however, was in no way intended to restrict the work to the Jewish dead. On the contrary, though it was a Jewish tragedy that first triggered off the composition, it was precisely the universality of his theme that Josephs wished to underline by avoiding the very specific associations, both musical and liturgical, of the Roman Mass for the Dead.

The Requiem's unusual emotional character results partly from the layout of the forces it employs. When Josephs first started planning the extension of the Quintet into a ten-movement choral and orchestral work begun and interspersed by quintet movements, he considered the possibility of re-scoring the quintet music for orchestra. By deciding against this, and instead keeping the original quintet of two violins, viola, and two cellos, he achieved a work of strongly individual dynamic design. [In Chicago, the string players were the Chicago Symphony String Quartet - Victor Aitay (concertmaster), Edgar Muenzer, Milton Preves (principal viola), and Frank Miller (principal cello, who had earlier been first cellist of the NBC Symphony under Toscanini) - plus cellist Leonard Chausow.] The music rises out of, and finally sinks again into, near-silence, and the use of the solo strings adds an extra dimension to the dynamic possibilities of normal orchestral scoring. By contrast with the biggest fortissimo the quintet can produce, even the quietest passages for chorus and orchestra assume a character of massive strength. The few loud outbursts are in turn able to make a striking impact, since the contrast with the quintet enables the composer to keep to a soft dynamic through a large proportion of the choral and orchestral music. A further level of differentiation beyond the purely dynamic is worth pointing out: Josephs has paid due attention to the need of choral harmonies for time to register. This consideration calls for writing quite different from the fleeting changes of harmony possible in non-vocal music-hence the characteristic breadth in the choral style of the Requiem, by comparison with the intensely involuted chromatic lines of the first two quintet movements. Just as the dynamics of the Requiem are prevailingly quiet, so its tempo is prevailingly slow. There is only one fast movement (No. III, Yehey Sh'mey Raba), and this also has more loud music than any of the other movements. In addition to the six vocal movements (four of them including a solo part for bass-baritone [in Chicago sung by Raffaele Arié]) and the three for string quintet, there is one purely orchestral movement-No. VII, De Profundis-which was allotted its place in the scheme of the Requiem early on in the planning but composed last of all. After the world premiere Josephs reversed the order of the last two movements: the work originally ended with the Monumentum movement for string quintet. If the restraint of this Requiem's grief is as noteworthy as its eloquence, the explanation perhaps lies in a particular characteristic of the Kaddish text: nowhere does it mention death or the dead. It is a funeral prayer concerned only with life and with the glorification of God, an apparent paradox especially apt for the many-layered expressive powers of music. It was, however, precisely the deployment of those powers through his remarkable melodic gift, combined with his fresh use of tonality, that constituted a serious impediment to the broader dissemination of Josephs' music in the Britain of the 1960s. The BBC was far and away the most important channel in the country for the performance of contemporary music-and from 1959 to 1972 the rather chillingly named post of BBC Controller of Music was held by William Glock (Sir William from 1970 on). Glock revitalized the broadcasting of the more recherché varieties of new music during his tenure, but he was also a somewhat doctrinaire member of what could be termed the “melody police”. As result, during a vital period in his career, Josephs found his music quite openly blocked from most avenues of British broadcasting. This was an ironic situation, because the Glock party's devotion to what I like to call the avant-derrière garde could be seen, when the serialist stranglehold on international composing styles came to be broken not very much later, as an ultimately reactionary posture. Having nevertheless held a respected position among his composer colleagues for many years, Wilfred Josephs suffered not only from that virtual suppression of his music by the BBC in the 1960s and beyond, but later on also from developments that choked off his career as an exceptionally fluent and communicative composer of film and television music (for 30 feature films, roughly the same number of documentary programs, and more than 120 British television productions). Essentially what happened was that the producers and directors with whom he had enjoyed long and fruitful collaborations began to disappear from the scene through retirement or death, while at the same time-the other half of the double whammy-instrumental scores were being supplanted in a substantial number of productions by synthesized soundtracks. In the last year of his life, Josephs told me, he had only one commercial commission. Meanwhile, the only commercial recording of the Requiem, an excellent LP conducted by David Measham for the Unicorn-Kanchana label with Australian orchestral and choral forces, disappeared from view with the transition to an all-CD medium. [As can be seen above, the Requiem, was later re-issued on CD.] Along with deteriorating health, the drying up of his principal source of income made Josephs' last months deeply depressing for him and for his friends. It would be at least a gesture of posthumous justice-as well as an illuminating and moving experience for today's listeners-if a major work like the Requiem could be restored to the repertoire, perhaps in salute to the 50th anniversary of its triumph in Milan back in 1963. Bernard Jacobson [The text has been slightly modified, and the links have been added. Image is from another source.] |

© 1997 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on June 13, 1997. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following month. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.