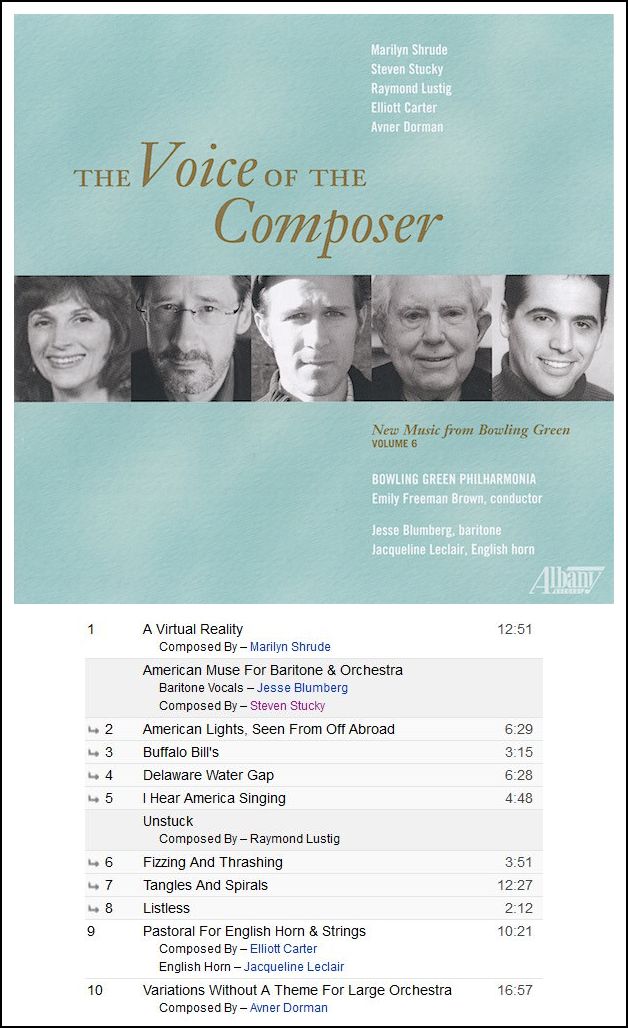

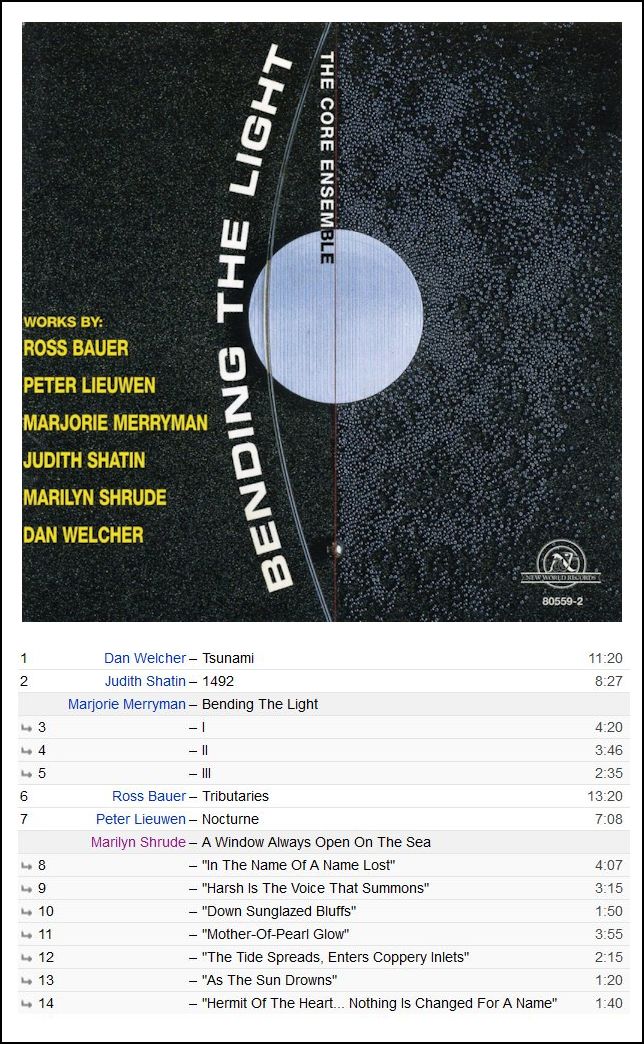

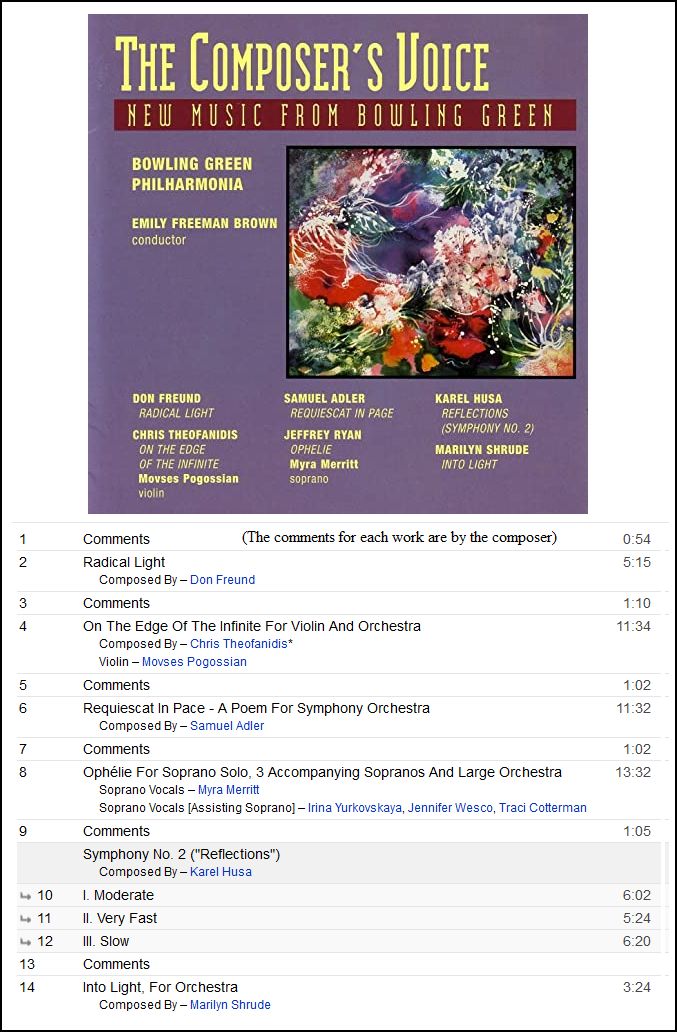

| Chicago-born composer Marilyn Shrude (July

6, 1946 - ) received degrees from Alverno College and Northwestern

University, where she studied with Alan Stout and M. William Karlins.

Among her more prestigious honors are those from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Rockefeller Foundation, Chamber Music America/ASCAP, Meet the Composer, National Endowment for the Arts, and the Ohio Arts Council. She was the first woman to receive the Kennedy Center Friedheim Awards for Orchestral Music (1984), and the Cleveland Arts Prize for Music (1998). Since 1977, Shrude has been on the faculty of Bowling Green State University, where she teaches and currently chairs the Department of Musicology/Composition/Theory. She is the founder of the MidAmerican Center for Contemporary Music (at Bowling Green), an international organization for the promotion of contemporary music, and past director of its Annual New Music & Art Festival. She continues to be active as a pianist and clinician with saxophonist John Sampen. In 2001, she was named a Distinguished Artist Professor of Music. |

Bruce Duffie: You’re both a composer and a teacher.

How are you able to divide your career, or is there just not enough

time in any day?

Bruce Duffie: You’re both a composer and a teacher.

How are you able to divide your career, or is there just not enough

time in any day? BD: Is composing at all a mystery

to you anymore?

BD: Is composing at all a mystery

to you anymore?

Shrude: Yes, I do, and so I’m careful

about saying yes if there’s not enough time.

Shrude: Yes, I do, and so I’m careful

about saying yes if there’s not enough time. BD: What about collegiate and other

teaching situations?

BD: What about collegiate and other

teaching situations?|

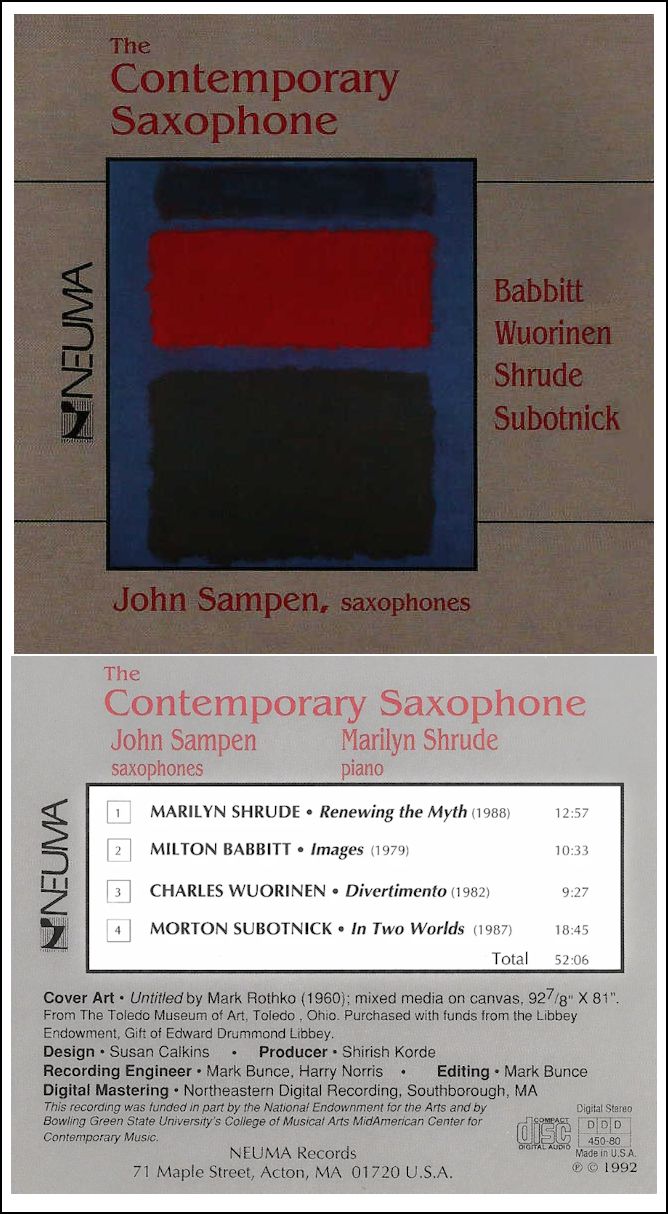

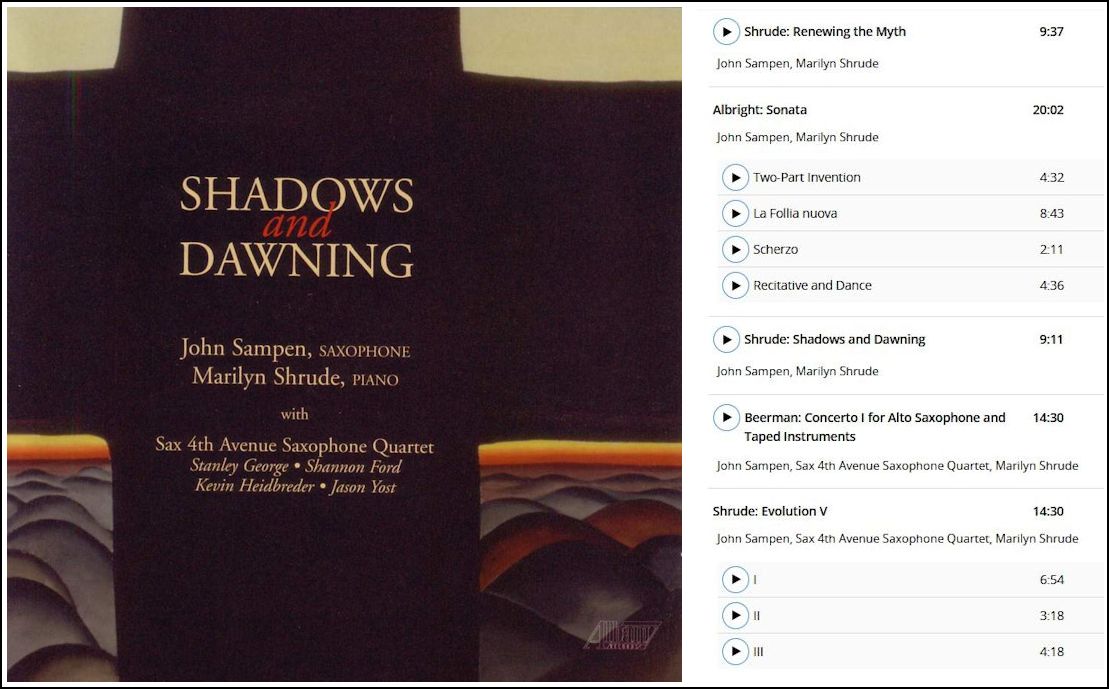

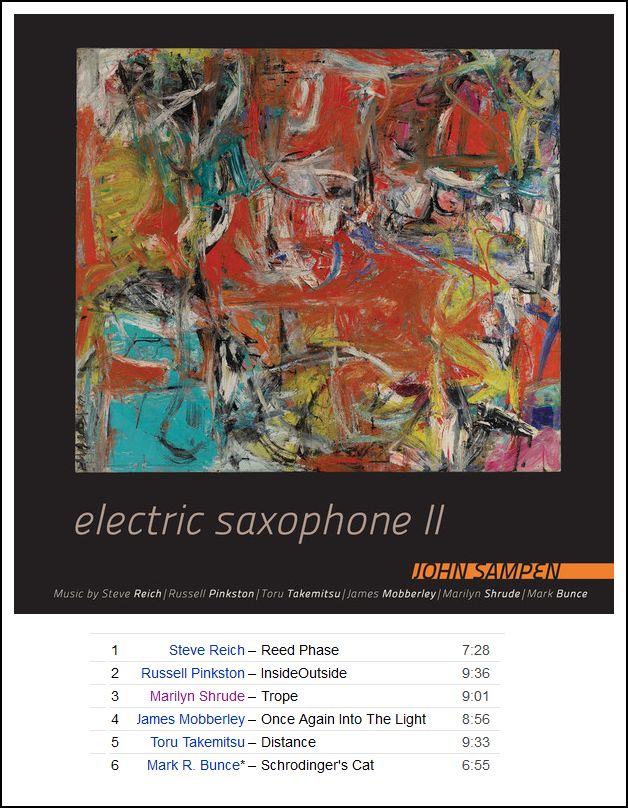

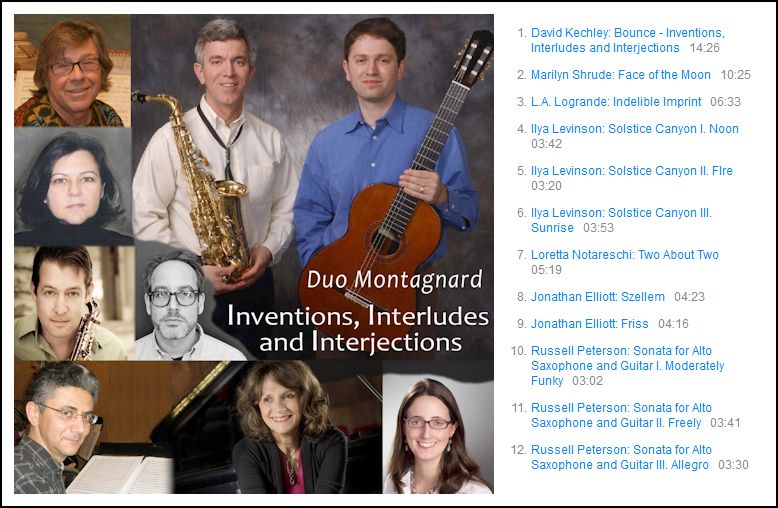

Sampen plays all styles, but specializes in new music. He has

commissioned over 60 new works from composers such as Samuel Adler, William Albright,

Milton Babbitt***,

William Bolcom*,

**, John Cage,

Michael Colgrass*,

John Harbison*,

Donald Martino*,

**, Ryo Noda, Pauline Oliveros,

Bernard Rands*,

Gunther Schuller*,

**, Elliott Schwartz,

Marilyn Shrude, Morton

Subotnick**, and Vladimir Ussachevsky.

|

BD: Your daughter is playing violin.

Have you written some things specifically for her?

BD: Your daughter is playing violin.

Have you written some things specifically for her? Shrude: [Hesitates] I’m a little

worried, but I don’t think it’s going to go away. I worry about

all the wonderful young people who are in school, just pouring their

hearts into their education, and I hope they can live out their dream.

Shrude: [Hesitates] I’m a little

worried, but I don’t think it’s going to go away. I worry about

all the wonderful young people who are in school, just pouring their

hearts into their education, and I hope they can live out their dream.

© 2001 Bruce Duffie

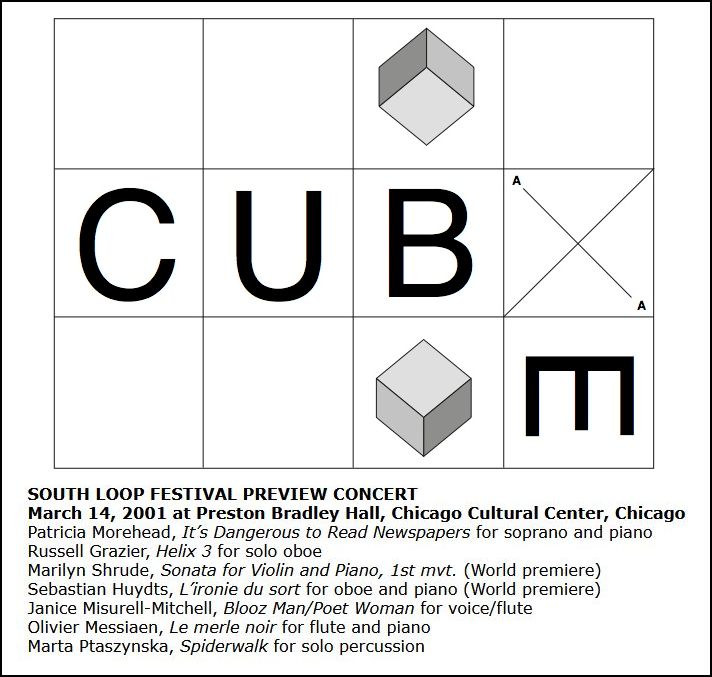

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 14, 2001. Portions were broadcast on WNUR the following year, and again in 2005, and 2017. This transcription was made in 2021, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.