|

Kay George Roberts was born September 16, 1950 in Nashville, Tennessee. She began playing the violin in the fourth grade for the Cermona Strings Youth ensemble. In 1964, she successfully auditioned for the Nashville Youth Symphony, which at the time was under the direction of Thor Johnson. At the age of 17, she was moved to the parent Nashville Symphony ensemble, where in 1971, she became the first violinist to represent the Nashville Symphony in the World Symphony Orchestra, which was directed by Arthur Fiedler. In 1972, Roberts graduated from Fisk University with her Bachelor of Arts in Music. She later attended Yale University School of Music, where she graduated with her Masters in Music in Conducting and Violin Performance in 1975, then her Masters in Musical Arts in Conducting in 1976. Later in 1986, she became the first woman and second black person to receive a doctoral degree in orchestral conducting from Yale University. During her time at Fisk University, Roberts was a fellow at Tanglewood, where she worked with Leonard Bernstein, serving as a violinist in his orchestra. During her time at Yale, she was under the tutelage of Otto-Werner Muller, who later arranged for her to conduct lead performances at the Nashville Symphony Orchestra, which was her debut as a conductor, and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. She has also conducted workshops, master classes, and seminars with Denis de Coteau, Seiji Ozawa, André Previn, and John Eliot Gardnier. Roberts is one of the very few female African American conductors in the world. In 1982, Roberts became the lead director of New Hampshire Philharmonic Orchestra. She also has guest conducted for orchestras across the world, including the Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana in Switzerland, the Cleveland Symphony, the Detroit Symphony, and Bangkok Symphony in Thailand. In 1978, she joined the faculty at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. She is the founder and musical director of the New England Orchestra, and the principal conductor for Opera North, Inc. in Philadelphia. She also founded the UMass Lowell String project, which helps K-12 students receive musical education.

* * *

* *

Kay George Roberts is the founder and music director of the Lowell-based New England Orchestra (NEO) with the mission of linking cultures through music. Her guest conducting engagements have included the Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago, Dallas, Detroit and Nashville Symphony orchestras as well as the Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana. She has served as a cover conductor for the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the Cleveland Orchestra and Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Ms. Roberts is the principal conductor for Opera North, Inc. in Philadelphia. Prof. Roberts studied at Tanglewood with Leonard Bernstein, Seiji Ozawa, Gustav Meier and at the Bachakademie Stuttgart with John Eliot Gardiner. An accomplished violinist, she is the first woman to earn a doctor of musical arts degree in conducting from Yale University where she studied with Otto-Werner Mueller. A champion of music education, she is the founder and director of the UMass Lowell String Project, an after-school string training program for Lowell public school children and the newly formed Lowell Youth Orchestra (LYO). The recipient of many honors, Roberts was awarded a "Certificate of Special Congressional Recognition" from the U.S. House of Representatives for her "outstanding and invaluable service to the community"; the University of Michigan "Presidential Professor" - "one of the highest honors bestowed on visiting artists and scholars" - for her work with the Sphinx Symphony; and the 2007 University of Massachusetts "President’s Public Service Award" in recognition of exemplary public service to the Commonwealth. In 2009, Roberts was selected as "Today's Woman" by Girls Incorporated

of Greater Lowell and appointed the first holder of the Nancy Donahue

Endowed Professorship in the Arts at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. == Biography from the UMASS website and other

sources |

|

Da Costa completed his Bachelor's at Queens College in 1952 and his Master's in theory and composition at Columbia University in 1956, studying with Otto Luening and Jack Beeson. He studied with Luigi Dallapiccola in Florence, Italy under a Fulbright Fellowship, and shortly thereafter in 1961 took positions teaching at Hampton University and the City University of New York. In 1970 he accepted a position at Rutgers University, where he taught until 2001. He died the following year at the age of 72. Da Costa was also a co-founder of the Society of Black Composers. He was an accomplished violinist, playing his own works as well as both classical and jazz music. He played on albums by Les McCann, Roland Kirk, Bernard Purdie, Roberta Flack, McCoy Tyner, Donny Hathaway, Felix Cavaliere, Willis Jackson, Eddie Kendricks, and others. His first music set to poetry being Tambourines by Langston Hughes. He also worked with choral groups, becoming the director of the Triad Choral in 1974, and played with both Symphony of the New World and several orchestras on Broadway theatre productions. Da Costa's works are marked by an infusion of elements of jazz, Caribbean music, and African music into the framework of Western classical music. The New York Times has described his music as "conservatively chromatic." As well as exploring Caribbean musical traditions and black American spirituals Da Costa also explored freely atonal music and serialism. |

| Born in Galveston, Texas

on January 5, 1930, Frederick Tillis was raised by his mother, Zelma

Bernice Gardner, née Tillis (1913–2004), his stepfather,

General Gardner, and his maternal grandparents, Willie Tillis and Jessie

Tillis-Hubbard (1893–1979).

In 1946, Tillis was accepted at Wiley College on a music scholarship, and thus became the first person in his family to receive a college education. He graduated from Wiley in 1949 with a B.A. in music, accepting the position of college band director there almost immediately. He married fellow Wiley music major Edna Louise Dillon at this time. They moved from Texas in 1951 so that Tillis could attend the University of Iowa for graduate music studies. At this time, he also decided to volunteer in the United States Air Force at the outbreak of the Korean War, and became director of the 356th Air Force Band. He later went back to get his PhD under the GI Bill at University of North Texas College of Music, but then returned to the University of Iowa to finish his doctoral studies. Completing his PhD in 1963, Tillis then held a succession of academic positions at Wiley College, Grambling College, and Kentucky State University. In 1970, Randolph Bromery recruited Tillis to the faculty of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and he and his family moved to Massachusetts. Joining the faculty as an associate professor of music, Tillis eventually held many faculty and administrative positions during his tenure. He retired in 1997 with the title of Professor Emeritus in the Department of Music and Dance. Tillis served as Director Emeritus of the University Fine Arts Center and Director of the Jazz in July Workshops in Improvisation. He died on May 3, 2020. Tillis wrote music which was influenced by Schoenberg, Bach, Prokofiev, Mussorgsky, African-American composers, and world music. |

© 1991 Bruce Duffie

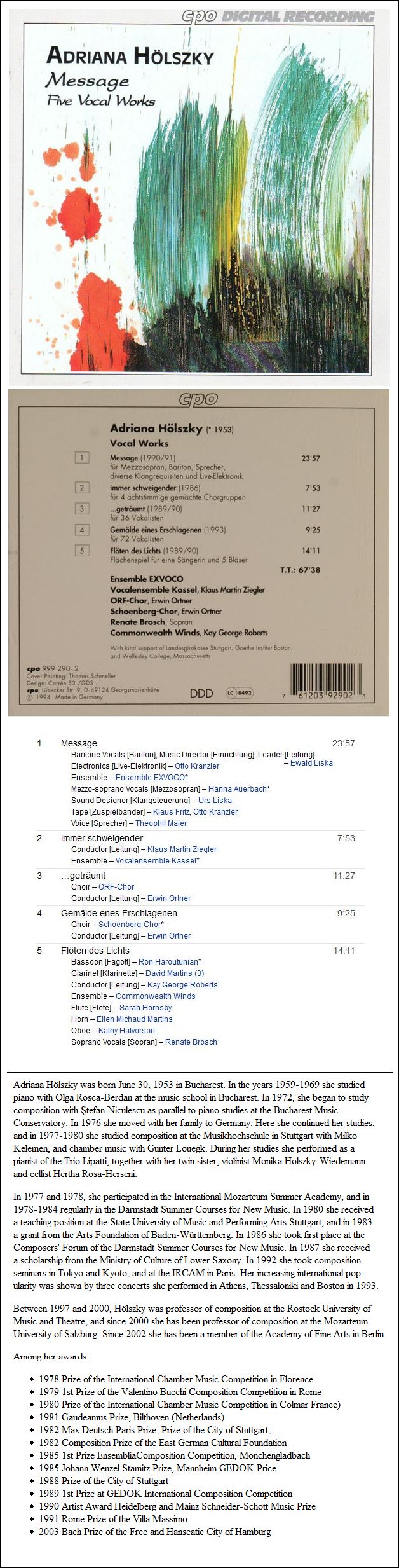

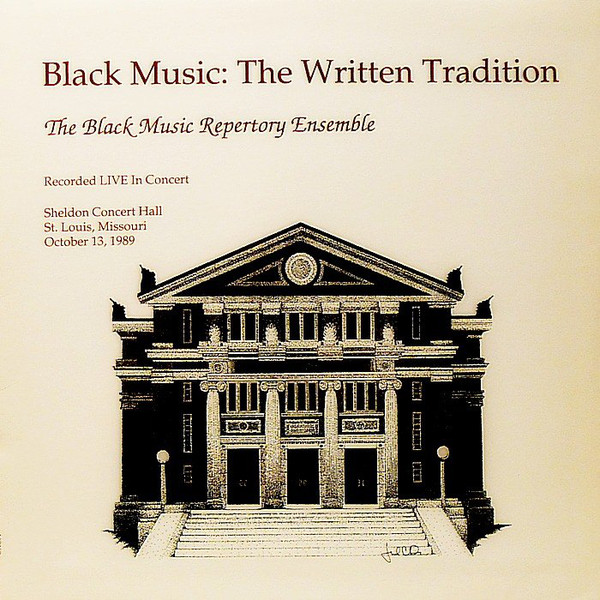

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on February 4, 1991. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following day, and again in 1995 and 2000. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.