A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

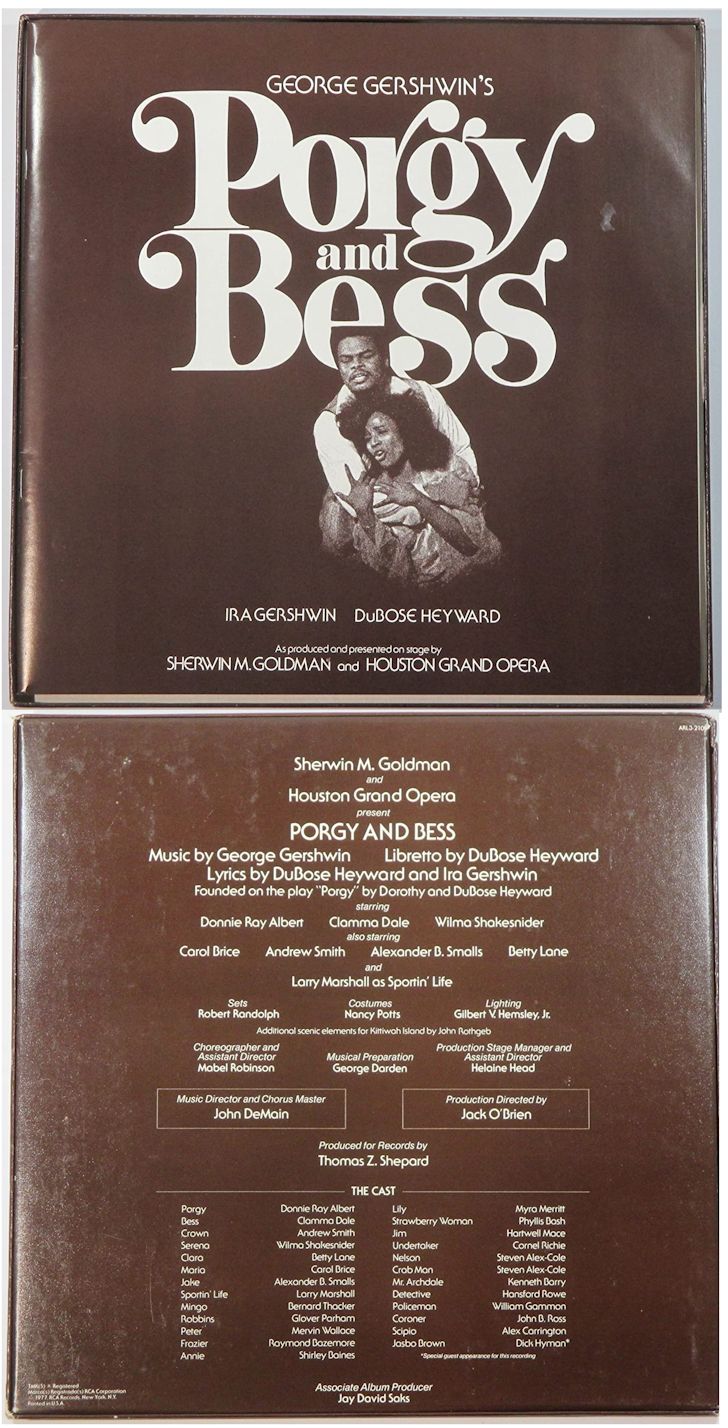

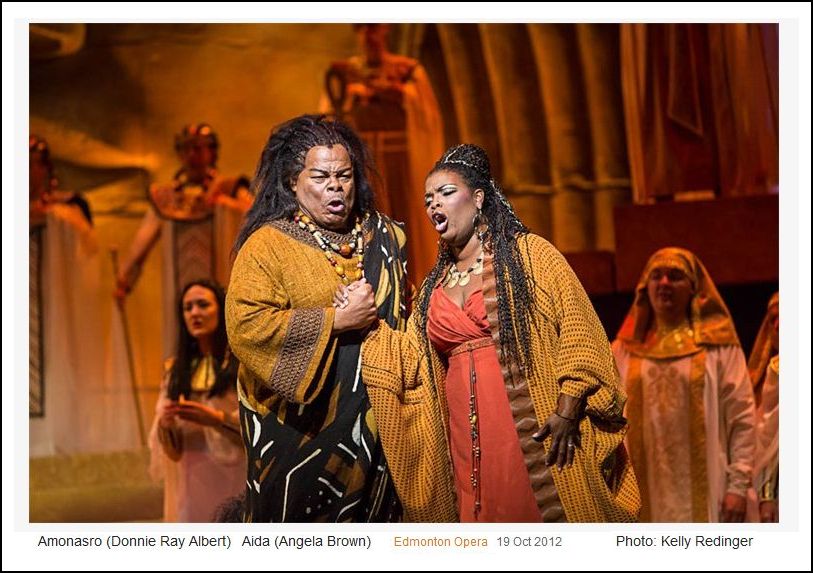

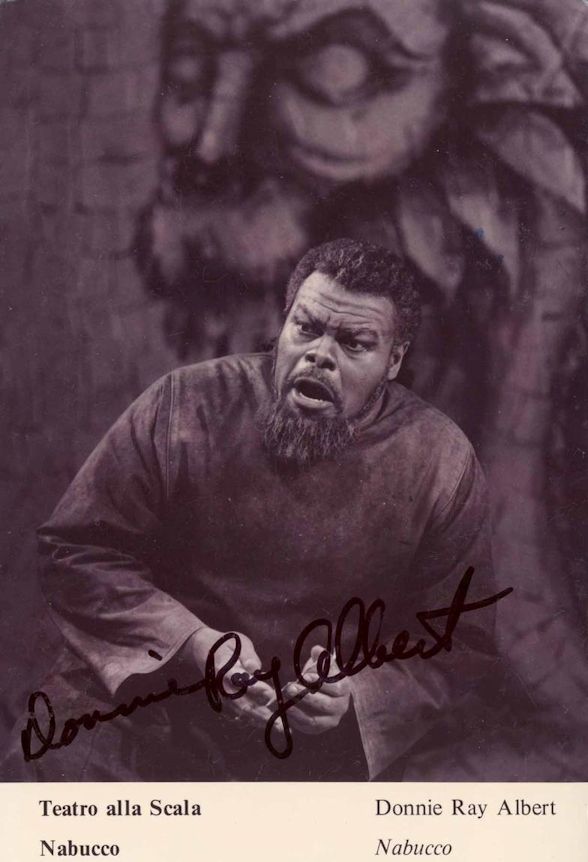

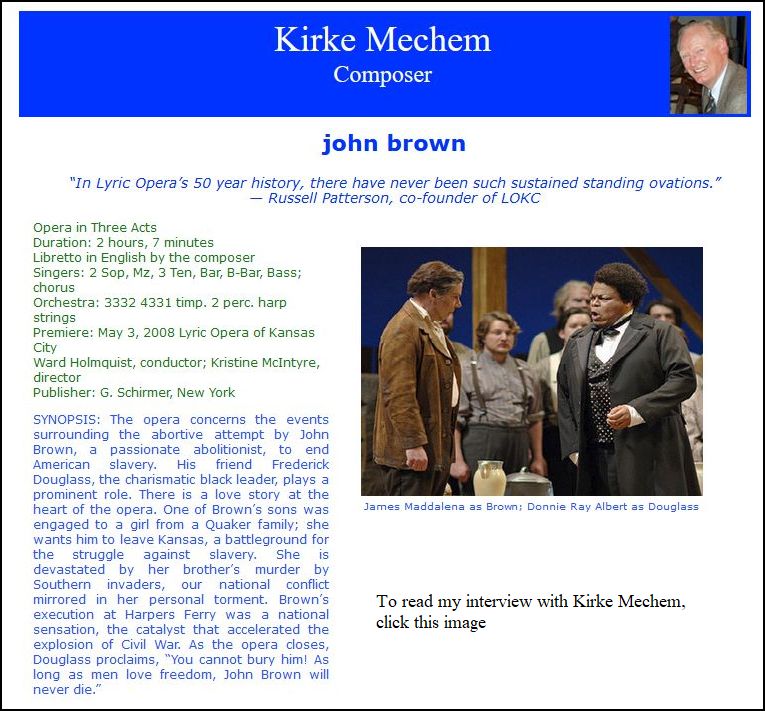

Donnie Ray Albert (born January 10, 1950) is an American operatic baritone who has had an active international career since 1976. Born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Albert graduated from McKinley Senior High School in 1968. He earned a Bachelor of Music degree from Louisiana State University in 1972. He went on to earn a Master of Music degree from Southern Methodist University where he studied with Thomas Hayward. Albert made his professional opera debut in May 1975 at the Houston Grand Opera in Scott Joplin's Treemonisha. The following year he returned to that house to sing the role of Jake Wallace in Giacomo Puccini's La Fanciulla del West and portray Porgy to the Bess of Clamma Dale in a highly lauded production of George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess. The production was transported to Broadway in New York City where it ran for a total of 122 performances from September 25, 1976 to January 9, 1977. The production's recording won a Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording. In 1978 he made his debuts at the New York City Opera and the Washington National Opera, and in 1979 he gave his first performance at the Lyric Opera of Chicago. During the 1980s, Albert was highly active with regional opera

companies in the United States; with his performance credits including

appearances with the Baltimore Opera, Cincinnati Opera, Dallas Opera,

Fort Worth Opera, New Orleans Opera, Portland Opera, and Tulsa Opera

among others. From 1981-1983 he made several appearances at the Vancouver

Opera. In 1982 he made his debut at the Opera Company of Boston and sang

at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. In 1984 he sang for the

first time at the San Francisco Opera, and that same year sang Porgy for

his debut at the Teatro Comunale Florence. He performed for the first time

with the Canadian Opera Company in 1986. In 1987 he made his debut at the

Michigan Opera Theatre and in 1989 he made his first appearance at the Florentine

Opera; both in the role of Porgy. In 1988 he embarked on a major tour of

Porgy and Bess in Europe. In 1996, Albert sang the title role in Richard Wagner's The Flying Dutchman at the Cologne Opera. At La Scala, he has performed the roles of as Amonasro Giuseppe Verdi's Aida, Hidraot in Christoph Willibald Gluck's Armide, and the title role in Verdi's Macbeth. Other roles he has performed on stage include Varlaam in Boris Godunov, Basilio in Rossini's The Barber of Seville, Count Monterone in Verdi's Rigoletto, Don Carlo in Verdi's Ernani, Don Fernando in Beethoven's Fidelio, Escamillo in Georges Bizet's Carmen, Ferrando in Verdi's Il trovatore, Iago in Verdi's Otello, Jack Rance in Giacomo Puccini's La fanciulla del West, Jochanaan in Richard Strauss' Salome, Nourabad in Bizet's Les pêcheurs de perles, Timur in Puccini's Turandot, Valentin in Charles Gounod's Faust, and the title role in Verdi's Nabucco, and the title role in Louis Gruenberg's The Emperor Jones. Albert has also had an active career as a concert singer. He has sung in concerts with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Minnesota Orchestra, the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, and the New York Philharmonic among others. == Biographical material from different sources

|

Albert: I don’t get as many concert engagements

as I would like. I just finished three in a row. One was

Elijah at Coral Ridge Presbyterian Church in Fort Lauderdale.

Dr. D. James Kennedy is the minister there, and I didn’t realize

what a big church that was. This was part of the concert series

that operates out of the church itself. I sang in church the following

Sunday, which was Palm Sunday, and then I wound up doing Messiah

as a benefit concert in the Meyerson Center in Dallas, which was fabulous.

It was one of the most exciting experiences I’ve ever had in a theater,

because there are such good acoustics. The performance itself was

also great. Then, two days later, I did a recital, and that’s

something I hadn’t done in almost two years.

Albert: I don’t get as many concert engagements

as I would like. I just finished three in a row. One was

Elijah at Coral Ridge Presbyterian Church in Fort Lauderdale.

Dr. D. James Kennedy is the minister there, and I didn’t realize

what a big church that was. This was part of the concert series

that operates out of the church itself. I sang in church the following

Sunday, which was Palm Sunday, and then I wound up doing Messiah

as a benefit concert in the Meyerson Center in Dallas, which was fabulous.

It was one of the most exciting experiences I’ve ever had in a theater,

because there are such good acoustics. The performance itself was

also great. Then, two days later, I did a recital, and that’s

something I hadn’t done in almost two years. BD: Do you encourage all of this

by performing some of them?

BD: Do you encourage all of this

by performing some of them? Albert: [Laughs] I don’t know... I

haven’t had to sweat in awhile. At one time, Porgy was the hardest

role that I had ever done, maybe physically because I was on my knees

for three hours. The range was just enormous, and it gets higher.

It doesn’t get lower as you go along. It’s just one of those

extensive roles the way it’s written.

Albert: [Laughs] I don’t know... I

haven’t had to sweat in awhile. At one time, Porgy was the hardest

role that I had ever done, maybe physically because I was on my knees

for three hours. The range was just enormous, and it gets higher.

It doesn’t get lower as you go along. It’s just one of those

extensive roles the way it’s written. Albert: Yes, right. The

fach change shocks a lot of people. Compared to a bass-baritone,

a baritone has many more notes to sing, and more words to sing.

Albert: Yes, right. The

fach change shocks a lot of people. Compared to a bass-baritone,

a baritone has many more notes to sing, and more words to sing.

Albert: Yes. Every singer

that comes into a situation will always test the acoustics to see

what he has to give, and what he shouldn’t give. It becomes a

game between you and the acoustics. It’s you against

the house, not you against the orchestra. It becomes a play on

the acoustics, and the esthetics that the environment projects.

Albert: Yes. Every singer

that comes into a situation will always test the acoustics to see

what he has to give, and what he shouldn’t give. It becomes a

game between you and the acoustics. It’s you against

the house, not you against the orchestra. It becomes a play on

the acoustics, and the esthetics that the environment projects. Albert: Yes, it takes me a while

to throw it off.

Albert: Yes, it takes me a while

to throw it off.|

William Grant Still, Jr. (May 11, 1895 – December 3, 1978) was an American composer of nearly 200 works, including five symphonies, four ballets, nine operas, over thirty choral works, plus art songs, chamber music and works for solo instruments. Often referred to as the "Dean of Afro-American Composers", Still was the first American composer to have an opera produced by the New York City Opera. Still is known primarily for his first symphony, Afro-American Symphony (1930), which was until 1950 the most widely performed symphony composed by an American. Born in Mississippi, he grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas, attended Wilberforce University and Oberlin Conservatory of Music, and was a student of George Whitefield Chadwick and later Edgard Varèse. Of note, Still was the first African American to conduct a major American symphony orchestra, the first to have a symphony performed by a leading orchestra, the first to have an opera performed by a major opera company, and the first to have an opera performed on national television. Due to his close association and collaboration with prominent African-American

literary and cultural figures, Still is considered to be part of the

Harlem Renaissance movement. * * *

* *

|

Albert: Rossini has gotten a lot

of treatment, though I don’t think his Otello has been mounted

in this country.

Albert: Rossini has gotten a lot

of treatment, though I don’t think his Otello has been mounted

in this country.|

Kelly, Lawrence Vincent (1928–1974). Lawrence Vincent Kelly, founder and general manager of the Dallas Civic Opera, was born in Chicago, Illinois, on May 30, 1928. He was the son of Patrick James and Thelma (Seabott) Kelly. He was a student at Chicago Music College (1942–45) at the same time that he attended Loyola Academy, from which he graduated. He went to Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., and returned to Chicago in 1950 to assist in the family real estate business; upon his father's death, he became business manager and later secretary-treasurer and director. He attended De Paul University Law School at night (1950–51), became a vice president and director of Dearborn Supply Company (1951–52), and established himself as an insurance broker in 1953. In 1953, Kelly was a co-founder, with Nicola Rescigno and Carol Fox, of the Lyric Theatre of Chicago, an opera company of which he was secretary-treasurer from 1953 to 1956 and managing director from 1954 to 1956. For two years, under his guidance, Chicago was the scene of "some of the most brilliant nights of opera seen in the United States," according to one writer. In June 1956, however, the founders of the company had a disagreement, and Kelly and Rescigno resigned. Kelly moved to New York City where he stayed a year. Considering where he might start a new opera company, he chose Dallas as a likely place. Through the efforts of music critic John Rosenfield, Kelly was brought to Dallas, and, in partnership with Nicola Rescigno, chartered the Dallas Civic Opera by March 1957. Kelly served as general manager, with Rescigno serving as artistic director and principal conductor. In November 1957 the company presented soprano Maria Callas in a concert; she had been presented by Kelly in her American debut three years earlier in Chicago. That first season only one opera, Rossini's L'Italiana in Algeri, was mounted; the cast was headed by Giulietta Simionato, and the production was designed and staged by Franco Zeffirelli, who made his American debut in it. This production set a quality standard for the future of the company, and Kelly's subsequent pattern of originality established the Dallas Civic Opera internationally. Over the next seventeen years Dallas opera lovers saw the American debut of such singers as Teresa Berganza, Jon Vickers, and Joan Sutherland. Kelly and Rescigno also introduced a distinguished group of theatrical directors and designers, and the company had its own scenic department, which built productions for other companies as well. Kelly was also a cofounder and director of the Performing Arts Foundation of Kansas City, Missouri. Early in 1974 Kelly took on the job of acting manager of the Dallas

Symphony Orchestra, which was in serious financial trouble. Several

months later he became gravely ill and had to resign that position.

He went to Kansas City, Missouri, for treatment and died there, on September

16, 1974. A requiem Mass was offered for him at Christ the King Catholic

Church in Dallas on September 19, the day before he was buried in the

family plot in Chicago. == Text by Eldon S. Branda, from the Handbook

of Texas , published by the Texas State Historical Association

|

|

Edward Purrington (December 6, 1929 – April 14, 2012) was an American opera director and artistic administrator. He began his career at the Santa Fe Opera in 1959 working in various positions through 1971, including stage manager, stage director, instructor in the Apprentice Program, business manager, and director of development and public relations. He had the good fortune of getting to work directly with many fine opera composers during his years with the SFO, such as Igor Stravinsky, Paul Hindemith, Gian Carlo Menotti, and Krzysztof Penderecki. From 1972-1974 Purrington was chairman of the Performing Arts Department

at the College of Santa Fe (now Santa Fe University of Art and Design).

He left that position to become the General Director of the Tulsa Opera

in 1974, a position he held for the next thirteen years. In 1987 he

became the Artistic Administrator of the Washington National Opera.

He stepped down from that position in 2001 but remained employed as

an Artistic Consultant for the company until his death in April 2012.

Purrington was also notably on the panel of judges of the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions. In 2002 he was honored by OPERA America for his "Distinguished Service to the Field of Opera." |

Albert: I think audiences come to be entertained.

A lot of people you get are the oldsters who are very astute opera

followers. They will come to compare, and everyone all of a

sudden becomes a critic. I find myself sometimes criticizing in

some areas if I go to a performance, but maybe that’s the reason I

don’t go to many performances. If I’m going to hear a singer sing,

I sometimes empathize so much with them, and I perspire just as much

as that person who is working, because either I know the material,

or I don’t know the material. But there are various aspects of what

an audience is there for. Some are there to be seen, and they don’t

know what the true essence of opera is all about. Carlisle Floyd

once said that when you write an opera — as

he does — some people go there in their

tuxes and still don’t get the gist of what went on on stage. They

don’t laugh if they go to a tremendous spoof on society, like The

Marriage of Figaro. They don’t laugh with things that are supposed

to be laughed at, and they’ve totally missed what the opera is about.

Albert: I think audiences come to be entertained.

A lot of people you get are the oldsters who are very astute opera

followers. They will come to compare, and everyone all of a

sudden becomes a critic. I find myself sometimes criticizing in

some areas if I go to a performance, but maybe that’s the reason I

don’t go to many performances. If I’m going to hear a singer sing,

I sometimes empathize so much with them, and I perspire just as much

as that person who is working, because either I know the material,

or I don’t know the material. But there are various aspects of what

an audience is there for. Some are there to be seen, and they don’t

know what the true essence of opera is all about. Carlisle Floyd

once said that when you write an opera — as

he does — some people go there in their

tuxes and still don’t get the gist of what went on on stage. They

don’t laugh if they go to a tremendous spoof on society, like The

Marriage of Figaro. They don’t laugh with things that are supposed

to be laughed at, and they’ve totally missed what the opera is about.

© 1990 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on May 12, 1990. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1995 and 2000. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.