|

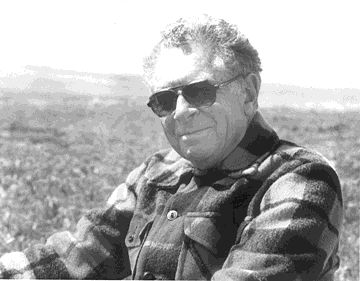

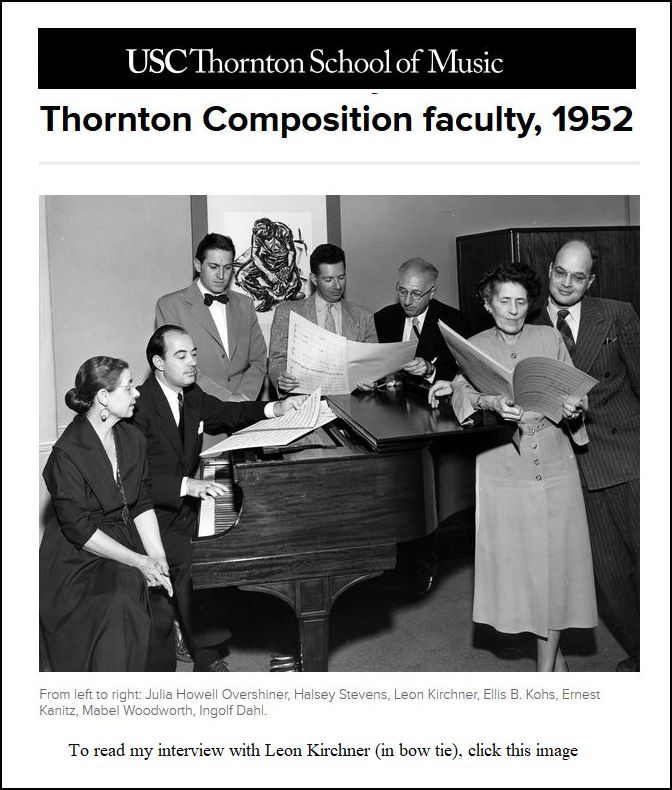

Ellis Bonoff Kohs (May 12, 1916 – May 17, 2000) was an American

composer, theory textbook author, and Professor at the University of

Southern California. Born in Chicago to Pauline Bonoff, a school teacher of Russian Jewish extraction, and Samuel C. Kohs, Ellis grew up in San Francisco, where he undertook his early musical studies at the San Francisco Conservatory. In 1928, his family moved to New York where he entered the Institute of Musical Art. He continued his studies at the University of Chicago, studying composition with Carl Bricken. After he completed his master's degree there in 1938, he returned to New York and enrolled at the Juilliard School, where he studied composition with Bernard Wagenaar. He also studied composition with Walter Piston, and musicology with Willi Apel and Hugo Leichtentritt at Harvard University. During World War II, Kohs conducted the Army and Air Force bands at Fort Benning, Georgia, St. Joseph, Missouri, and Nashville. After the war, he joined the faculty of Wesleyan University, where he taught composition from 1946 to 1948, and the Kansas City Conservatory, where he taught during the summers of 1946 and 1947. He moved to California in 1948 and undertook teaching positions at the College of the Pacific, and at Stanford University. He began teaching at USC in 1950 where he remained on the faculty for 38 years, serving as chairman of the music theory department for several years. Kohs' stage works include Amerika (1969), an opera based

on Kafka's novel, Lohiau and Hiiaka, a choreographed setting of a

Hawaiian legend, and incidental music for Shakespeare's Macbeth (1947).

His orchestral works include a Concerto for Orchestra (1942), a

Cello Concerto (1947), a Violin Concerto (1980) and two

symphonies (1950 and 1957). His vocal works included settings of Navajo

songs and The Lord Ascendant, based on The Epic of Gilgamesh.

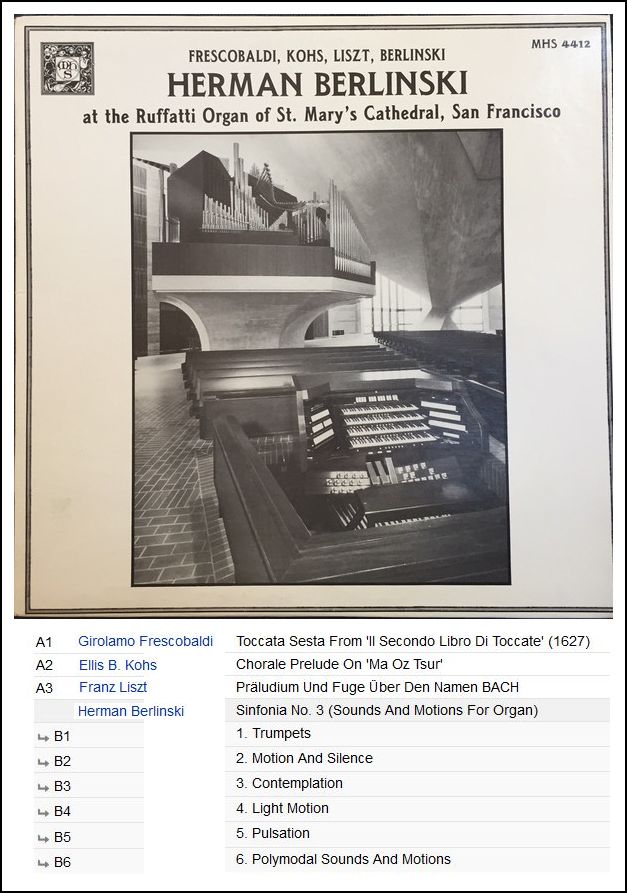

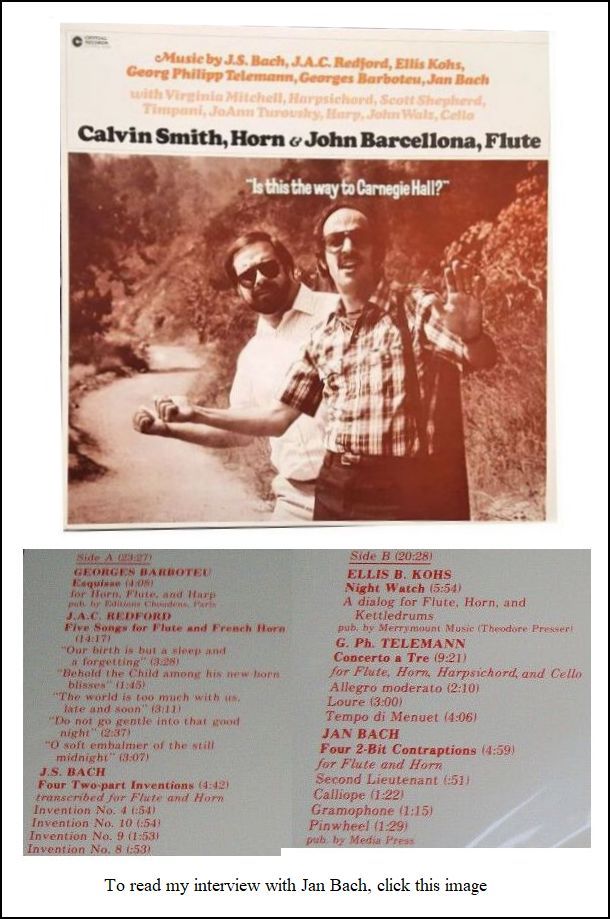

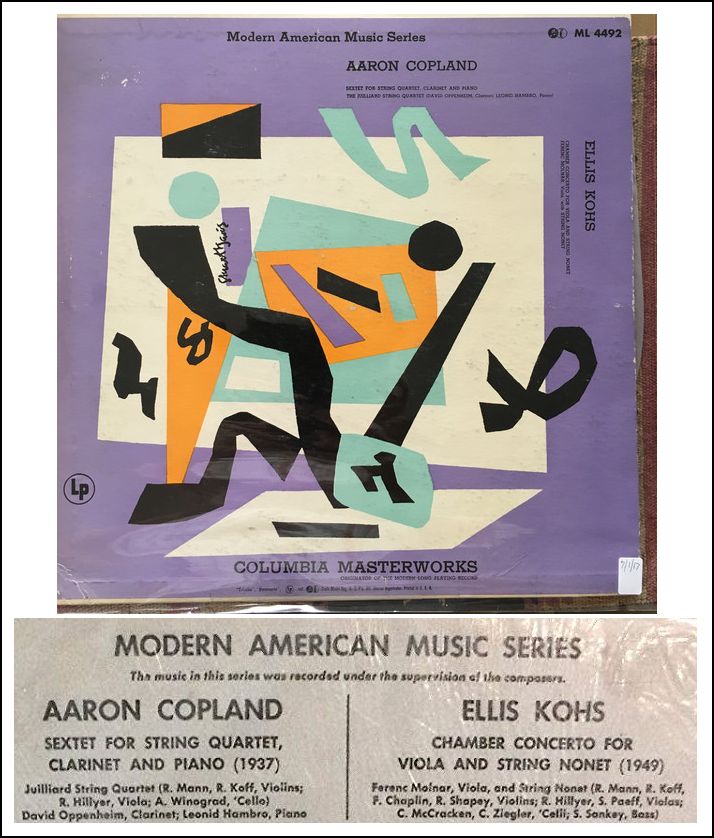

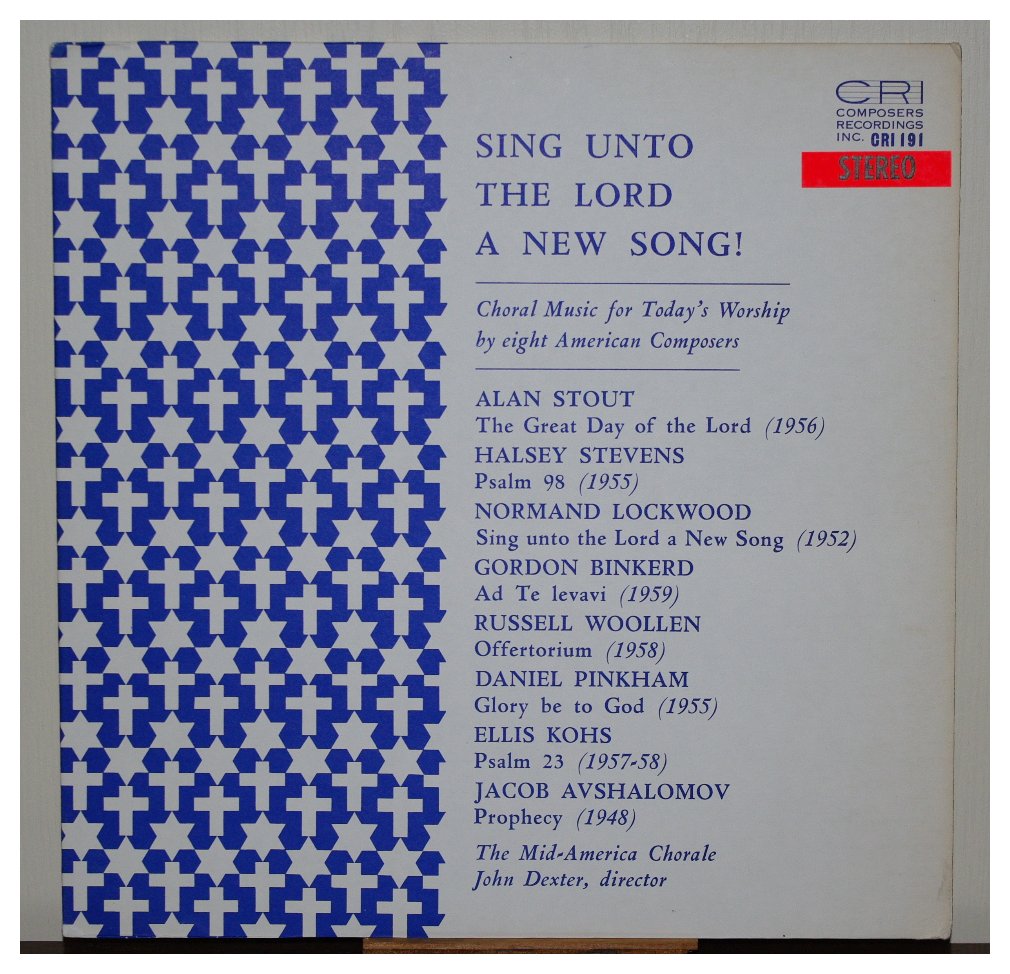

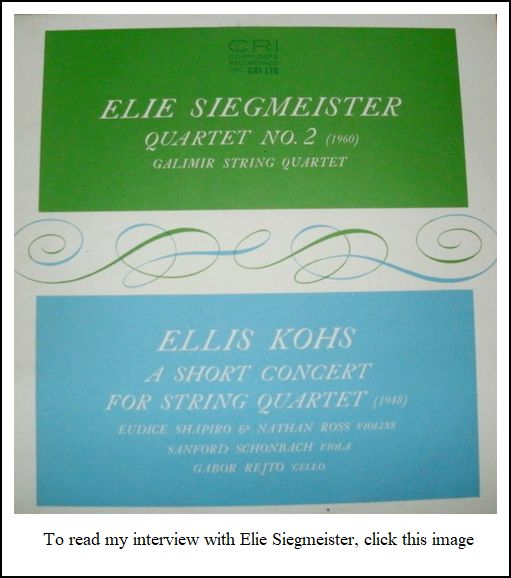

He also composed solo and chamber music. A recording of Kohs' music, including the Chamber Concerto,

Passacaglia for Organ and Strings, Toccata for Harpsichord

or Piano, Short Concert for String Quartet, and Sonatina

for Violin and Piano was released on Composers Recordings, Inc.

See my interview with Ralph Shapey

|

People have often asked me how I decided

where in the radio programming I would put my interview guests. The

answer was quite simple... Early on, I stumbled on a very workable

system, which was to celebrate Round Birthdays. So, when a guest

would turn fifty, or sixty, or sixty-five, or similar, they would get a

program of music with sections of the interview. This system had the

advantage of not only being color-blind and gender-blind, it removed the

stress of worrying if I had given this one enough exposure, or neglected

that other one.

People have often asked me how I decided

where in the radio programming I would put my interview guests. The

answer was quite simple... Early on, I stumbled on a very workable

system, which was to celebrate Round Birthdays. So, when a guest

would turn fifty, or sixty, or sixty-five, or similar, they would get a

program of music with sections of the interview. This system had the

advantage of not only being color-blind and gender-blind, it removed the

stress of worrying if I had given this one enough exposure, or neglected

that other one. Kohs: There are few musical heroes.

Copland can be regarded as a hero, although I don’t think there

are very many composers today who wish to emulate him, or feel that there’s

any need to emulate him. He has accomplished what he has accomplished,

and he is still held up as a hero. Perhaps there is a small number

of others — very few

— who would be held in similar esteem and affection.

Kohs: There are few musical heroes.

Copland can be regarded as a hero, although I don’t think there

are very many composers today who wish to emulate him, or feel that there’s

any need to emulate him. He has accomplished what he has accomplished,

and he is still held up as a hero. Perhaps there is a small number

of others — very few

— who would be held in similar esteem and affection. Kohs: One would hope that it comes somewhat prepared,

as it were. It’s very hard for an audience to enjoy any kind of

music of any period without having some kind of background. So,

one hopes that it will be an audience which has previous experience in

Twentieth Century music... and earlier music, because

music which is not a reflection of the art as a whole in some way, or

does not fit into the art as a whole, is going to be very limited.

I, myself, draw on elements of music of many periods and styles, and I

hope that they’re well-assimilated. For a listener to pick up

all these innuendoes of the world, they would need to have a background.

Otherwise, much will be lost.

Kohs: One would hope that it comes somewhat prepared,

as it were. It’s very hard for an audience to enjoy any kind of

music of any period without having some kind of background. So,

one hopes that it will be an audience which has previous experience in

Twentieth Century music... and earlier music, because

music which is not a reflection of the art as a whole in some way, or

does not fit into the art as a whole, is going to be very limited.

I, myself, draw on elements of music of many periods and styles, and I

hope that they’re well-assimilated. For a listener to pick up

all these innuendoes of the world, they would need to have a background.

Otherwise, much will be lost. Kohs: That’s right. Those were

very important, and significant years of my life. At the moment,

five years doesn’t seem like a very long time. I’ve seen many

generations of composers come and go here at the University of Southern

California, and four or five years go by very quickly. But those

were very important years of my life, and I’m very happy that fate led

me to Chicago at that particular time. If I had known then I was

going to be a composer, I might have been tempted to go elsewhere, but

it was only while I was there that I have realized that music was to be

my professional life.

Kohs: That’s right. Those were

very important, and significant years of my life. At the moment,

five years doesn’t seem like a very long time. I’ve seen many

generations of composers come and go here at the University of Southern

California, and four or five years go by very quickly. But those

were very important years of my life, and I’m very happy that fate led

me to Chicago at that particular time. If I had known then I was

going to be a composer, I might have been tempted to go elsewhere, but

it was only while I was there that I have realized that music was to be

my professional life. BD: [Laughs] That’s a wonderful book [which

is a collection of bad reviews of mostly great music by very famous composers].

I use that quite often when I’m giving lectures on old masters. I

pull out bad reviews of Beethoven and others. On that subject,

what’s the role of the critic?

BD: [Laughs] That’s a wonderful book [which

is a collection of bad reviews of mostly great music by very famous composers].

I use that quite often when I’m giving lectures on old masters. I

pull out bad reviews of Beethoven and others. On that subject,

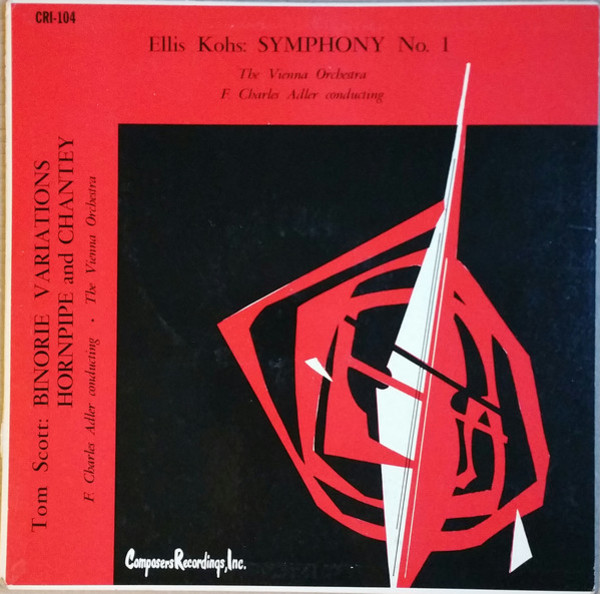

what’s the role of the critic? Kohs: I have a special fondness

for that because it was asked for by Pierre Monteux, whom I got to know

through Alfred Frankenstein. He recommended my very early Concerto

for Orchestra, which was performed under Monteux’s direction with

the San Francisco Symphony back in the early 1940s. I went backstage

to see him after another concert, and quite abruptly he said to me, “Why

don’t you write something for me?” He had performed a contemporary

work on the program, which he felt, perhaps, obliged to do, but didn’t have

his heart in it. He thought I might write something he would enjoy,

so I decided that was the time to write my first symphony. I did, and

dedicated it to him. He conducted its first performance.

Kohs: I have a special fondness

for that because it was asked for by Pierre Monteux, whom I got to know

through Alfred Frankenstein. He recommended my very early Concerto

for Orchestra, which was performed under Monteux’s direction with

the San Francisco Symphony back in the early 1940s. I went backstage

to see him after another concert, and quite abruptly he said to me, “Why

don’t you write something for me?” He had performed a contemporary

work on the program, which he felt, perhaps, obliged to do, but didn’t have

his heart in it. He thought I might write something he would enjoy,

so I decided that was the time to write my first symphony. I did, and

dedicated it to him. He conducted its first performance. Kohs: Sometimes alternation was

necessary, and other times I had to change a little bit of the German,

or I had to change a little bit of the English. It varied. I

wanted to keep the original as much as possible. Sometimes it was

not possible, so it varied as I went along. Fortunately, I had some

help from a lady who was a native German, and had a real sense of what

music was all about. She helped me a great deal.

Kohs: Sometimes alternation was

necessary, and other times I had to change a little bit of the German,

or I had to change a little bit of the English. It varied. I

wanted to keep the original as much as possible. Sometimes it was

not possible, so it varied as I went along. Fortunately, I had some

help from a lady who was a native German, and had a real sense of what

music was all about. She helped me a great deal. BD: I was going to ask if there’s a

correlation between the opera house and the concert hall.

BD: I was going to ask if there’s a

correlation between the opera house and the concert hall.

BD: [Laughs] Even if

it’s a good score, it probably leaves a bad taste in the conductor’s mouth.

BD: [Laughs] Even if

it’s a good score, it probably leaves a bad taste in the conductor’s mouth.© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on March 5, 1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following May, and again in 1993 and 1998. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.