| Cornell MacNeil was born Sept. 24,

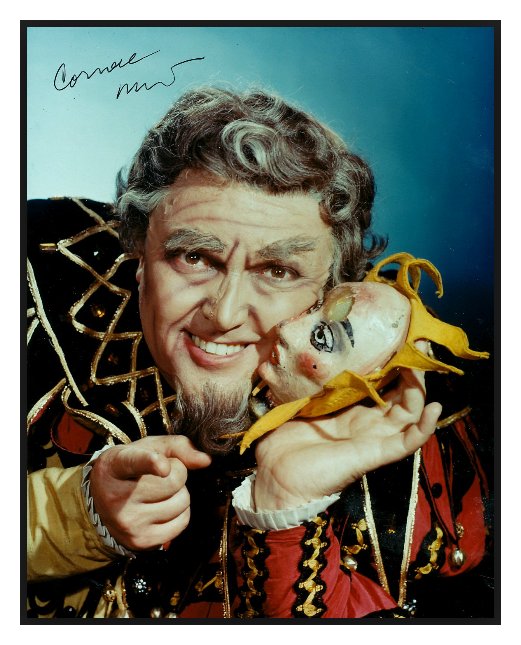

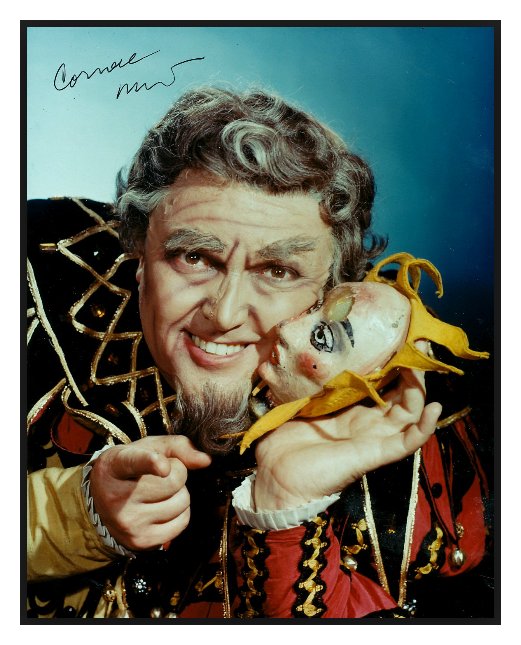

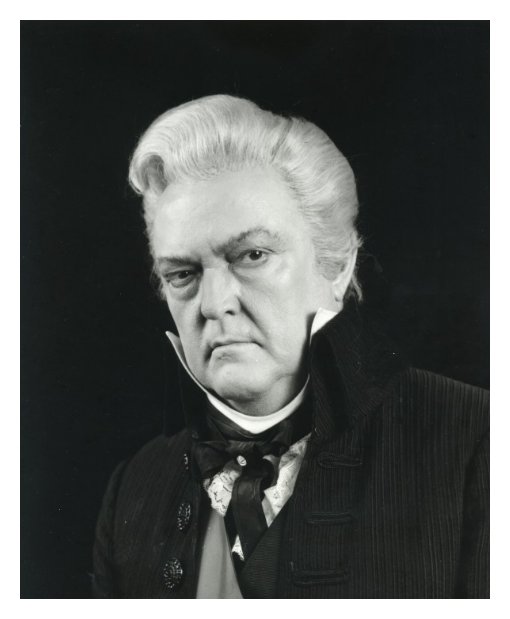

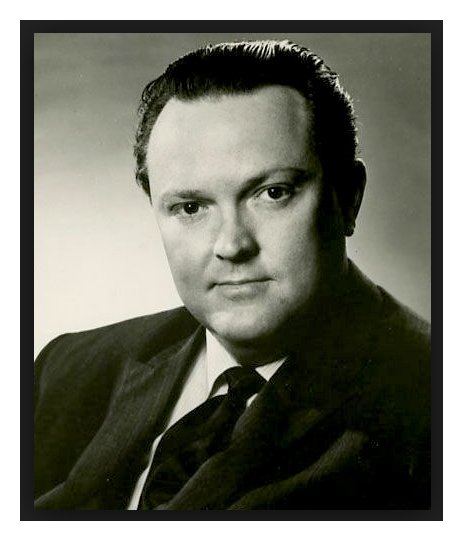

1922, in Minneapolis. His father was a dentist, his mother a singer. He told

the New York Post in 1973, “I can’t remember when I didn’t sing.” He performed

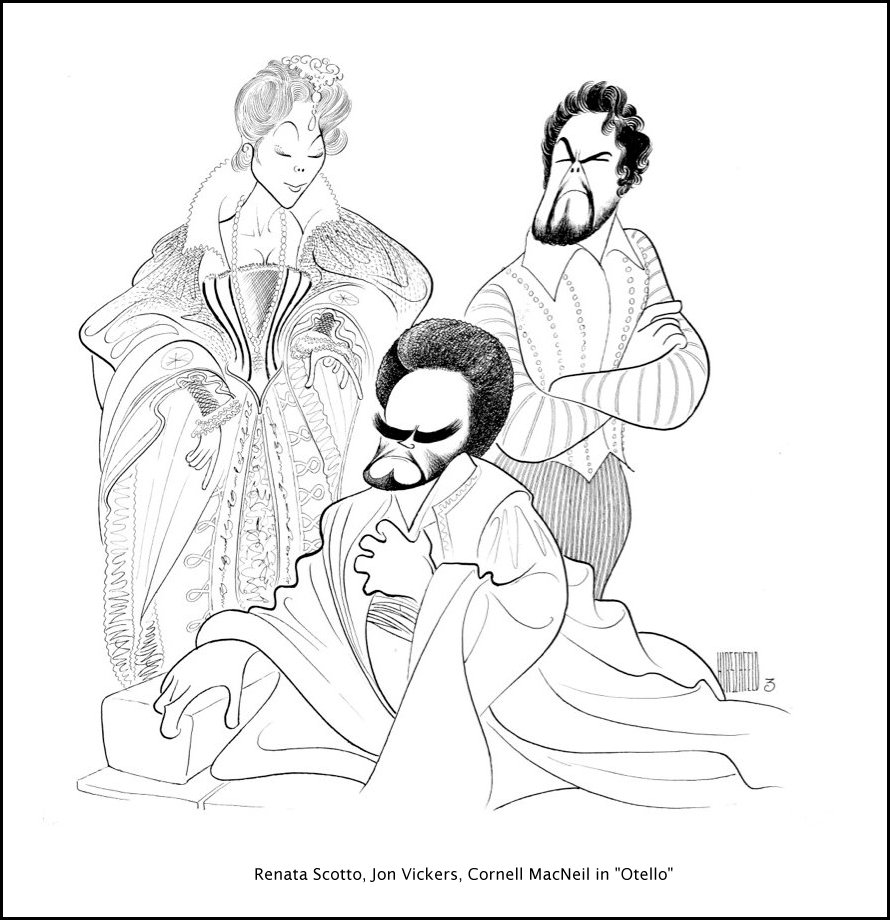

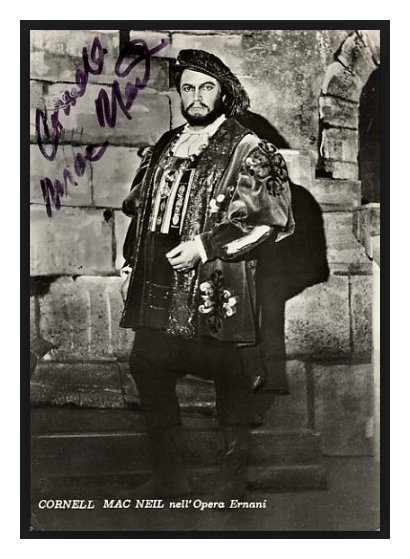

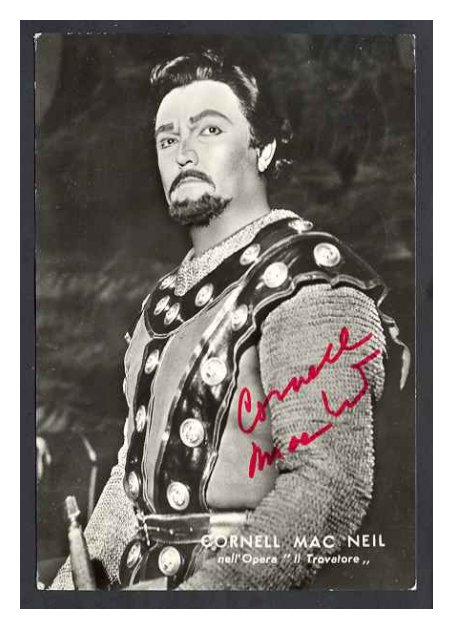

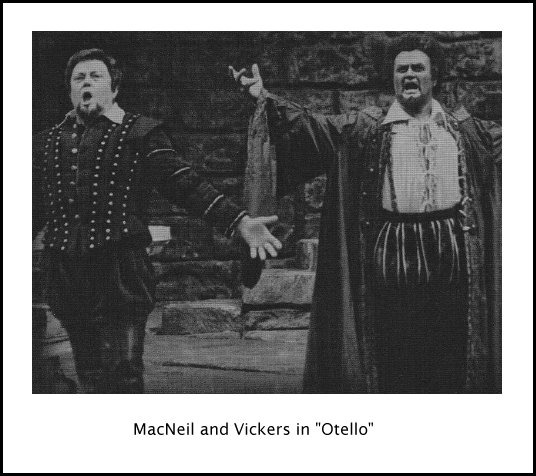

on radio at 12. Severe asthma kept him out of the military during World War II. When he decided not to go to college, his father stopped supporting him. Mr. MacNeil found work as a machinist at a Pratt & Whitney engine plant in Hartford, Conn., while studying at the nearby Hartt School conservatory. He began to find small parts in musicals and summer-stock theater and made his operatic debut in 1950 in Gian Carlo Menotti’s “The Consul.” Mr. MacNeil was 30 before he gave up his job as a supervisor at a Bulova watch factory in New York to devote himself to opera. He sang with the New York City Opera from 1953 to 1956, earning rapturous reviews, then traveled widely around the world. Mr. MacNeil, who possessed a robust voice and a powerful stage presence, had modest success before leaping to operatic stardom in 1959. In the same month, he made triumphant debuts at La Scala in Milan and the Metropolitan Opera in New York. After appearing in Verdi’s “Ernani” at La Scala on March 5, 1959, he was summoned to substitute for an ailing Robert Merrill in the title role of Verdi’s “Rigoletto” at the Metropolitan Opera on March 21. Mr. MacNeil arrived in New York on the day of the performance, with only enough time to be fitted for a costume before the opening curtain. Over the next 28 years, Mr. MacNeil sang more than 600 times at the Met, including more than 100 performances of “Rigoletto.” Music critic Winthrop Sargeant wrote in the New Yorker in 1966 that Mr. MacNeil was “one of the truly great Rigolettos, with a voice of immense size and a fine grasp of character.” He became equally renowned for his portrayals of Iago in Verdi’s “Otello,” Count di Luna in Verdi’s “Il Trovatore” and Scarpia, the malevolent police chief in Giacomo Puccini’s “Tosca.” As president of the American Guild of Musical Artists, Mr. MacNeil represented performers in negotiations with the Met’s management for years. In retirement, he lived in Toronto and Charlottesville, where he had an elaborate woodworking shop. He died on July 15, 2011. His first marriage, to singer Margaret Gavan, ended in divorce. Survivors include his wife since 1972, violinist Tania Rudensky of Charlottesville; five children from his first marriage; two grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren. -- Part of the obituary in the Washington Post by Matt Schudel

|

|

Cornell MacNeil at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1957 - Manon Lescaut (Lescaut) with Tebaldi, Bjoerling, Badioli, Velis; Serafin Cavalleria rusticana (Alfio) with Simionato, Sullivan, Nadell; Kopp Pagliacci (Silvio & Prologue) with Likova, Del Monaco, Gobbi, Caruso; Bartoletti, Rosing (dir) 1958 - Falstaff (Ford) with Gobbi, Tebaldi, Moffo, Simionato, Canali, Misciano; Serafin Madama Butterfly (Sharpless) with Tebaldi, DiStefano, Canali, Caruso; Kondrashin Pagliacci (Silvio (& Prologue?*)) with Likova, DeStefano, Gobbi, Caruso; Serafin, Rosing (dir) Rigoletto (Rigoletto) with Moffo, Bjoerling, Wildermann, Steffan, Krainik (Giovanna); Sebastian 1965 - Rigoletto (Rigoletto) with Scotto, Kraus, Vinco, Cassei, Krainik (Giovanna); Sebastian 1976 - Tosca (Scarpia) with Neblett, Pavarotti, Tajo, Giorgetti, Andreolli; López-Cobos, Gobbi (dir) 1982 - Pagliacci (Tonio) with Barstow, Vickers, Carlson, Gordon; Cillario, Zeffirelli (prod) * According to the annals as posted on the Lyric Opera website, MacNeil sang "Silvio & Prologue" in 1957. In 1958, MacNeil is only listed as "Silvio". However, the production was the same, and Gobbi (who was again singing "Tonio") had sung the title role in Gianni Schicchi earlier in the evening. Vladimir Rosing was the director both years, but the veteran conductor, Tulio Serafin, might have changed in 1958 what the then-young Bruno Bartoletti had allowed the previous year. -- Note: Names which are links

(both in this box and below) refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website

|

CMacN: What’s a recording? Don’t you accept

that? Who’s going to say we can throw them all out – the

Supreme Court?

CMacN: What’s a recording? Don’t you accept

that? Who’s going to say we can throw them all out – the

Supreme Court? BD: How difficult is it for Cornell MacNeil to

say no?

BD: How difficult is it for Cornell MacNeil to

say no?

CMacN: No. I don’t think it has to be done

that way. The adversary situation between unions and management in the

theatrical business is necessary. I think it’s good, and I don’t think

it’s always destructive. There are certain things built into it for

which nobody will ever know the reason why. Nobody knows where it started

out that orchestra members began getting more money than chorus members,

and it is a constant thorn in the side of negotiations and it never will

be resolved. By the way it is exactly the same way in Moscow.

The orchestra gets more money than the chorus. It’s been that way in

any theater I have come across.

CMacN: No. I don’t think it has to be done

that way. The adversary situation between unions and management in the

theatrical business is necessary. I think it’s good, and I don’t think

it’s always destructive. There are certain things built into it for

which nobody will ever know the reason why. Nobody knows where it started

out that orchestra members began getting more money than chorus members,

and it is a constant thorn in the side of negotiations and it never will

be resolved. By the way it is exactly the same way in Moscow.

The orchestra gets more money than the chorus. It’s been that way in

any theater I have come across.  CMacN: I’m accustomed to the best of all worlds,

of course. [Both laugh] It’s a little disconcerting to find

that, after the A-flat that you were talking about on the opening night,

the audience burst into applause and I had to try and quieten them down.

They didn’t understand what was going on at all. My assumption is

there’s a lot of people out there who never heard Pagliacci. My God, I thought everybody

knew Pagliacci! They didn’t

know that I wasn’t through yet! There’s a great danger in this, and

I see it happening. They take a look at the bottom line, as it’s become

known, and see that it’s good, and this translates into the idea that there’re

doing well — which isn’t the same thing at all.

It simply means that there’s a lot of money out there that wants the most

prestigious ticket they can find.

CMacN: I’m accustomed to the best of all worlds,

of course. [Both laugh] It’s a little disconcerting to find

that, after the A-flat that you were talking about on the opening night,

the audience burst into applause and I had to try and quieten them down.

They didn’t understand what was going on at all. My assumption is

there’s a lot of people out there who never heard Pagliacci. My God, I thought everybody

knew Pagliacci! They didn’t

know that I wasn’t through yet! There’s a great danger in this, and

I see it happening. They take a look at the bottom line, as it’s become

known, and see that it’s good, and this translates into the idea that there’re

doing well — which isn’t the same thing at all.

It simply means that there’s a lot of money out there that wants the most

prestigious ticket they can find. CMacN: I have never been driven to sing everything

that was ever written, although some people seem to be. I have also

regularly taken vacations every year in the summer, and I work with my maestro

nearly every day. We only live five or ten minutes apart, and all through

the season if possible I work with him on Friday, Saturday and Sunday.

The end result of it is that my willingness to undertake things outside of

repertoire, which I have moved along in, was very slim. I didn’t go

to festivals because I thought it was more important to repair the things

that I was going to do for the next season. So I have never worked as

much as most other modern singers have, and the end result of it is that I

have not had an enormous amount of time for new things.

CMacN: I have never been driven to sing everything

that was ever written, although some people seem to be. I have also

regularly taken vacations every year in the summer, and I work with my maestro

nearly every day. We only live five or ten minutes apart, and all through

the season if possible I work with him on Friday, Saturday and Sunday.

The end result of it is that my willingness to undertake things outside of

repertoire, which I have moved along in, was very slim. I didn’t go

to festivals because I thought it was more important to repair the things

that I was going to do for the next season. So I have never worked as

much as most other modern singers have, and the end result of it is that I

have not had an enormous amount of time for new things. CMacN: No, not that. It’s professional, otherwise

they wouldn’t get away with it, but it’s uninteresting. Just terribly

dull most of the time. It can only be that way. That’s what the

lack of time for rehearsal does to opera all over. You are constantly

in a defensive rehearsal situation, unless you have absolute faith in the

people that surround you and the stage director as well. Sometimes the

conductor even comes into it. If he doesn’t look up at the right moment,

you’re hung! Or if you don’t look at him at the right moment, he’s

hung. It’s all mutual. But you have to have a lot of faith in

your colleagues to do this all the time in a very hurried rehearsal situation,

because you can’t do anything overt dramatically. You can’t get yourself

out on that dramatic limb that you can’t crawl off of by yourself, because

you’re liable to get out there and get it cut off with no place to go.

If you need help from your colleagues to get you off a dramatically very overt

thing, you better be damn sure of the colleague. So it tends to even

things out unfortunately. Part of the things that operatic stage directors

always want to do is overcome this particular aspect of it. Felsenstein

overcame it by having a four hour rehearsal with every chorus member, and

six months of rehearsals. Almost invariably singers were so bored that

they couldn’t perform when they got to the performance. [In

1947 Walter Felsenstein created the Komische Oper in East Berlin, where he

worked as director until his death in 1975.] Other directors

want to do some dramatic thing that will make people talk.

CMacN: No, not that. It’s professional, otherwise

they wouldn’t get away with it, but it’s uninteresting. Just terribly

dull most of the time. It can only be that way. That’s what the

lack of time for rehearsal does to opera all over. You are constantly

in a defensive rehearsal situation, unless you have absolute faith in the

people that surround you and the stage director as well. Sometimes the

conductor even comes into it. If he doesn’t look up at the right moment,

you’re hung! Or if you don’t look at him at the right moment, he’s

hung. It’s all mutual. But you have to have a lot of faith in

your colleagues to do this all the time in a very hurried rehearsal situation,

because you can’t do anything overt dramatically. You can’t get yourself

out on that dramatic limb that you can’t crawl off of by yourself, because

you’re liable to get out there and get it cut off with no place to go.

If you need help from your colleagues to get you off a dramatically very overt

thing, you better be damn sure of the colleague. So it tends to even

things out unfortunately. Part of the things that operatic stage directors

always want to do is overcome this particular aspect of it. Felsenstein

overcame it by having a four hour rehearsal with every chorus member, and

six months of rehearsals. Almost invariably singers were so bored that

they couldn’t perform when they got to the performance. [In

1947 Walter Felsenstein created the Komische Oper in East Berlin, where he

worked as director until his death in 1975.] Other directors

want to do some dramatic thing that will make people talk. BD: Is there going to be a time when you give your

management notice that you are going to go home and work in your garden?

BD: Is there going to be a time when you give your

management notice that you are going to go home and work in your garden?This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 11, 1982. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1987, 1992 and 1997. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.