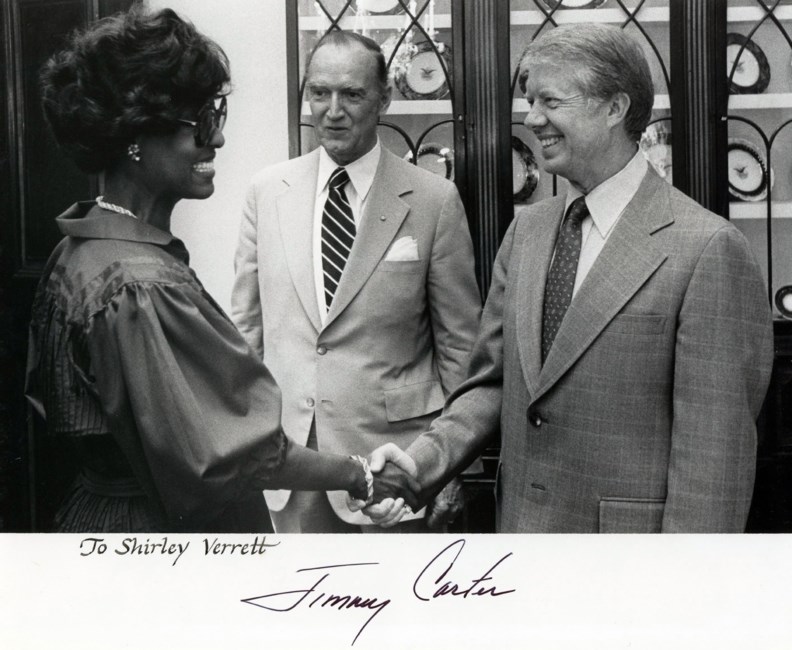

| Shirley Verrett (May 31, 1931 – November

5, 2010) was an American operatic mezzo-soprano who successfully transitioned

into soprano roles, i.e. soprano sfogato. Verrett enjoyed great

fame from the late 1960s through the 1990s, particularly well known for

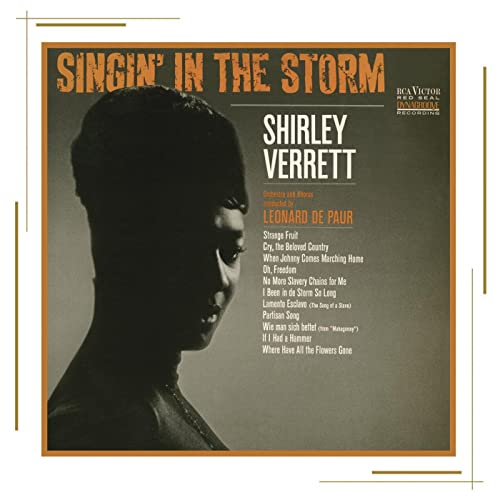

singing the works of Verdi and Donizetti. Born into an African-American family of devout Seventh-day Adventists in New Orleans, Louisiana, Verrett was raised in Los Angeles, California. She sang in church and showed early musical abilities, but initially a singing career was frowned upon by her family. Later Verrett went on to study with Anna Fitziu and with Marion Szekely Freschl at the Juilliard School in New York. In 1961 she won the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions. In 1957, Verrett made her operatic debut in Britten's The Rape of Lucretia. In 1958, she made her New York City Opera debut as Irina in Kurt Weill's Lost in the Stars. In 1959, she made her European debut in Cologne, Germany in Nicolas Nabokov's Rasputins Tod. In 1962, she received critical acclaim for her Carmen in Spoleto, and repeated the role at the Bolshoi Theatre in 1963, and at the NY City Opera in 1964. Verrett first appeared at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in 1966 as Ulrica in Un ballo in maschera. She appeared in the first concert ever televised from Lincoln Center

in 1962, and also appeared that year in the first of the Leonard Bernstein

Young People's Concerts ever televised from that venue,

in what is now Avery Fisher Hall.

Beginning in the late 1970s she began to tackle soprano roles, including

Selika in L'Africaine, Judith in Bartók's Bluebeard's

Castle, Lady Macbeth in Macbeth, Madame Lidoine in Poulenc's

Dialogues of the Carmelites (Met1977), Tosca, Norma (from

Boston 1976 till Messina 1989), Aida (Boston 1980 and 1989), Desdemona

(Otello) (1981), Leonore (Fidelio) (Met 1983), Iphigénie

(1984–85), Alceste (1985), Médée (Cherubini) (1986). Her

Tosca was televised by PBS on Live from the Met in December

1978, just six days before Christmas. [Hirschfeld drawing of the cast is

shown below, followed by the DVD release.] In 1990, Verrett sang Dido in Les Troyens at the inauguration of the Opéra Bastille in Paris, and added a new role at her repertoire: Santuzza in Cavalleria rusticana in Sienna. In 1994, she made her Broadway debut in the Tony Award-winning revival of Rodgers and Hammerstein's Carousel at Lincoln Center's Vivian Beaumont Theater, playing Nettie Fowler. In 1996 Verrett joined the faculty of the University of Michigan

School of Music, Theatre & Dance as a Professor of Voice and the

James Earl Jones Distinguished University Professor of Voice. The preceding

year at the National Opera Association Gala Banquet and Concert honoring

Mattiwilda Dobbs,

Todd Duncan, Camilla Williams and Robert McFerrin, Verrett said: "I'm

always so happy when I can speak to young people because I remember those

who were kind to me that didn't need to be. The first reason I came tonight

was for the honorees because I needed to say this. The second reason I

came was for you, the youth. These great people here were the trailblazers

for me. I hope in my own way I did something to help your generation, and

that you will help the next. This is the way it's supposed to be. You

just keep passing that baton on!" -- Names which are links in this box

and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

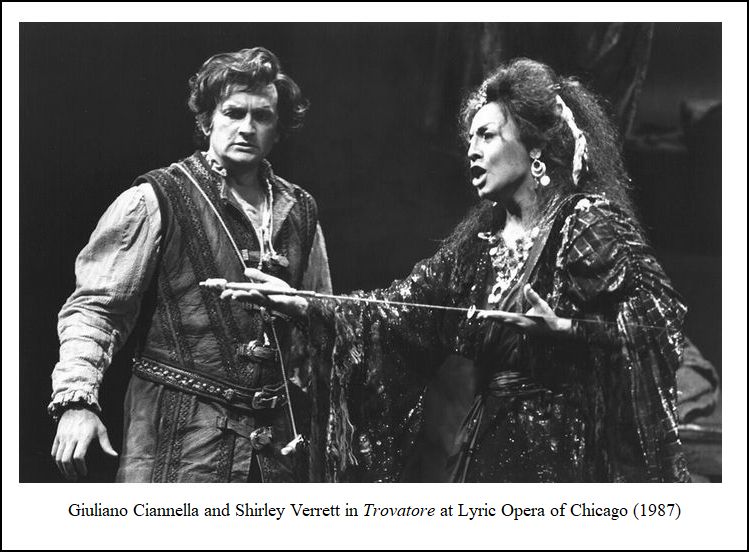

In the fall of 1987, Verrett made her

debut (!) with Lyric Opera of Chicago as Azucena in Il Trovatore.

By that time, she was already world-famous, so I began by asking

the obvious question . . . . .

In the fall of 1987, Verrett made her

debut (!) with Lyric Opera of Chicago as Azucena in Il Trovatore.

By that time, she was already world-famous, so I began by asking

the obvious question . . . . . Verrett: I started my career as a recitalist.

I didn’t want to call myself an opera singer, although I had been

put in the opera department. When I began to sing in Europe

— first at Covent Garden, and then

in Florence, Italy, where I made my European debuts in the early ’60s

— I decided that I would call myself

an opera singer. But even at that time, sixty or seventy per cent

of my work still remained recital and concerts. That has flipped

over to being just the opposite now, an about-face, where I do seventy

per cent opera, and about thirty per cent recitals and concerts. Because

I wanted to be a good wife and a good mother

— we have one daughter, and I wanted to be with her

a lot — it made me stay very, very loose

about the opera, and now the Gershwin and the lighter music come into

my life. I still feel it’s very Classical Music, if you want

to call it that, because I think it’s great music. It’s not Serious

Music, as we think of it, but it’s great music, and I hope it will live

as long as many of the old composers — like

Verdi.

Verrett: I started my career as a recitalist.

I didn’t want to call myself an opera singer, although I had been

put in the opera department. When I began to sing in Europe

— first at Covent Garden, and then

in Florence, Italy, where I made my European debuts in the early ’60s

— I decided that I would call myself

an opera singer. But even at that time, sixty or seventy per cent

of my work still remained recital and concerts. That has flipped

over to being just the opposite now, an about-face, where I do seventy

per cent opera, and about thirty per cent recitals and concerts. Because

I wanted to be a good wife and a good mother

— we have one daughter, and I wanted to be with her

a lot — it made me stay very, very loose

about the opera, and now the Gershwin and the lighter music come into

my life. I still feel it’s very Classical Music, if you want

to call it that, because I think it’s great music. It’s not Serious

Music, as we think of it, but it’s great music, and I hope it will live

as long as many of the old composers — like

Verdi. BD: You’re a very forward-looking opera singer.

BD: You’re a very forward-looking opera singer. Verrett: Exactly. You’re always digging

to find how much deeper you can go into this character, trying to

find how much more can you show to the audience that this character

has going for himself or herself. In this particular case, the

thing that was really a big change for me was in the last act, in the

prison. I am not lying down at the beginning of that scene, when

Manrico asks me if I can’t sleep. Usually, I’m turning and being

restless, which precipitates the question. This time, Sonja Frisell

said that all the time she’d seen Azucenas try to sleep at that moment,

and she wanted to try something else. She wanted me to try walking

around tiredly, trying to find a way to get out of this place. She

is hemmed in, and this gypsy is not used to being confined. So why

would she very meekly rest there? The directions from Verdi’s

time say that she’s tired, she’s worn out. At the end, when she

has gotten her revenge, and tells Manrico that his brother has been

put to death, she has disintegrated so much that she absolutely dies

at that point. So, there is no punishment for her because she

dies, but in this particular production we don’t do that. I move

around restlessly and at a certain moment I go to sleep.

Verrett: Exactly. You’re always digging

to find how much deeper you can go into this character, trying to

find how much more can you show to the audience that this character

has going for himself or herself. In this particular case, the

thing that was really a big change for me was in the last act, in the

prison. I am not lying down at the beginning of that scene, when

Manrico asks me if I can’t sleep. Usually, I’m turning and being

restless, which precipitates the question. This time, Sonja Frisell

said that all the time she’d seen Azucenas try to sleep at that moment,

and she wanted to try something else. She wanted me to try walking

around tiredly, trying to find a way to get out of this place. She

is hemmed in, and this gypsy is not used to being confined. So why

would she very meekly rest there? The directions from Verdi’s

time say that she’s tired, she’s worn out. At the end, when she

has gotten her revenge, and tells Manrico that his brother has been

put to death, she has disintegrated so much that she absolutely dies

at that point. So, there is no punishment for her because she

dies, but in this particular production we don’t do that. I move

around restlessly and at a certain moment I go to sleep. BD: When you’re looking at the rushes

or the finished product, do you find that when you thought something

was coming across, something different was coming across?

BD: When you’re looking at the rushes

or the finished product, do you find that when you thought something

was coming across, something different was coming across? Verrett: I think so, because we didn’t

do it three times. It was interesting how it was recorded.

I’m learning as I go along. For the movie sound track they must

put certain other kinds of mikings, or something. I don’t know

what the terminology is, but it’s something I want to learn about. Some

of the people who were selling the recording were saying that they felt

the same way I did about it. The record should have been used in

the theaters because every house is different, and most of them have

dilapidated equipment, or equipment that doesn’t lend itself to opera

recordings. I would think that the better of the two sounds should

have been used. That’s my opinion. I remember when we saw it

in Cannes, at one point we had to ask them to raise the sound a little bit

because it was just so hard to hear. Cannes has supposedly wonderful

equipment, but it had to be adjusted, and I’m just hoping that they are

adjusting it to the right place for each house in each movie theater it

goes into.

Verrett: I think so, because we didn’t

do it three times. It was interesting how it was recorded.

I’m learning as I go along. For the movie sound track they must

put certain other kinds of mikings, or something. I don’t know

what the terminology is, but it’s something I want to learn about. Some

of the people who were selling the recording were saying that they felt

the same way I did about it. The record should have been used in

the theaters because every house is different, and most of them have

dilapidated equipment, or equipment that doesn’t lend itself to opera

recordings. I would think that the better of the two sounds should

have been used. That’s my opinion. I remember when we saw it

in Cannes, at one point we had to ask them to raise the sound a little bit

because it was just so hard to hear. Cannes has supposedly wonderful

equipment, but it had to be adjusted, and I’m just hoping that they are

adjusting it to the right place for each house in each movie theater it

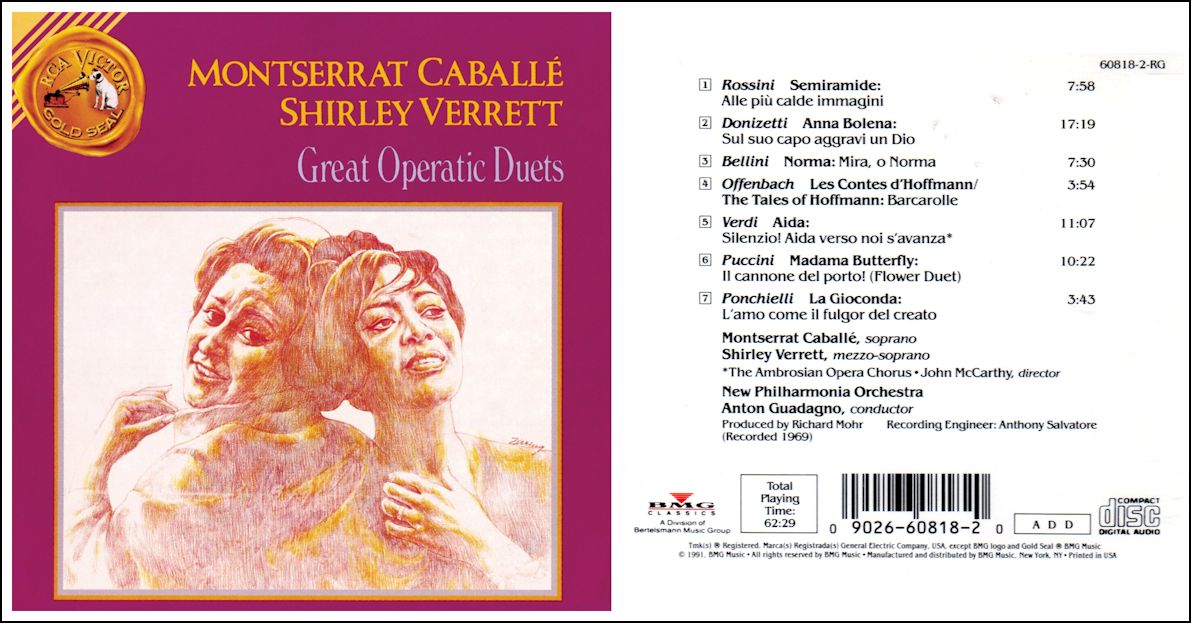

goes into. Verrett: Yes, Amneris, but I took it

out of the repertoire. I sing Aïda now.

Verrett: Yes, Amneris, but I took it

out of the repertoire. I sing Aïda now.

|

She is often credited with having contributed to Verdi's first

successes, starring in a number of his early operas, including the role

of Abigaille in the world premiere of Nabucco in 1842. A highly gifted

singer, Strepponi excelled in the bel canto repertoire and spent much of

her career portraying roles in operas by Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti,

and Gioachino Rossini, often sharing the stage with tenor Napoleone Moriani and baritone

Giorgio Ronconi. Donizetti wrote the title role of his opera Adelia

specifically for Strepponi. She was described as possessing a "limpid, penetrating, smooth voice, seemly action, a lovely figure; and to Nature's liberal endowments she adds an excellent technique"; her "deep inner feeling" was also lauded. Both her personal and professional life were complicated by overwork, by at least three known pregnancies, and by her vocal deterioration which caused her to retire from the stage by the age of 31, in 1846 when she moved to Paris to become a singing teacher. While it is known that she had a professional relationship with Verdi from the time of his first opera, Oberto in 1839, they became a couple by 1847 when they lived together in Paris, then moved to Busetto in 1849, married in 1859, and remained together until the end of her life. |

BD: Do you ever regret that Il Trovatore was

not called La Zingara [The Gypsy]?

BD: Do you ever regret that Il Trovatore was

not called La Zingara [The Gypsy]?

| The Opéra-Comique is a Paris

opera company, which was founded around 1714 by some of the popular theatres

of the Parisian fairs. In 1762 the company was merged with, and for a time

took the name of its chief rival the Comédie-Italienne at

the Hôtel de Bourgogne, and was also called the Théâtre-Italien

up to about 1793, when it again became most commonly known as the Opéra-Comique.

Today the company's official name is Théâtre national

de l'Opéra-Comique, and its theatre, with a capacity of around

1,248 seats, sometimes referred to as the Salle Favart (the third on this

site), is located in Place Boïeldieu, in the 2nd arrondissement of

Paris, not far from the Palais Garnier, one of the theatres of the Paris

Opéra. The musicians and others associated with the Opéra-Comique have made important contributions to operatic history and tradition in France, and to French opera. Its current mission is to reconnect with its history, and discover its unique repertoire, to ensure production and dissemination of operas for the wider public. Mainstays of the repertory at the Opéra-Comique during its history have included the following works which have each been performed more than 1,000 times by the company: Cavalleria Rusticana, Le chalet, La dame blanche, Le domino noir, La fille du régiment, Lakmé, Manon, Mignon, Les noces de Jeannette, Le pré aux clercs, Tosca, La bohème, Werther and Carmen, the last having been performed more than 2,500 times. [Photo below shows the theatre at the time of the premiere of Carmen (March 3, 1875)].

|

BD: In French or Italian?

BD: In French or Italian? BD: You just sing!

BD: You just sing!© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at her hotel in Chicago on September 23, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1991, 1992, and 1996. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.