Janice Misurell-Mitchell is a composer, flutist and vocal artist who lives and works in Chicago. She teaches about music and politics and contemporary music at the School of the Art Institute. In addition to her teaching she presents lecture-recitals and workshops related to her compositions, extended techniques for the flute, and the relation of text and music.

Misurell-Mitchell offers a unique vision of American contemporary

music. Drawing on traditional Western European classical elements, she

fashions pieces that reach into the rich sources of jazz, popular and

ethnic music. “Her attempts at stretching music’s boundaries—by incorporating

improvisation and performance art…have produced refreshing results.”

[Ted Shen, Chicago Reader]

Misurell-Mitchell has been a featured composer and performer at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the UNC Greensboro New Music Festival, Art Chicago, the International Alliance for Women in Music Congress in Beijing, the Voices of Dissent series at the Bowling Green College of Musical Arts, the Festival of Winds in Novara, Italy, and the Randspiele Festival in Berlin. Her honors include grants from Meet the Composer, the Illinois Arts Council, the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs, residencies at the Atlantic Center for the Arts and the Ragdale Foundation, and awards and commissions from the National Flute Association, the Youth Symphony of DuPage, the International Alliance for Women in Music, Northwestern University and numerous performers. She was chosen as a “Chicagoan of the Year” in classical music for 2002 by the Chicago Tribune. Her works are performed throughout the United States and Europe and have been played on the Public Broadcasting Network, at the National Flute Association Conventions, the Museum of Contemporary Art and Symphony Center in Chicago, and at Carnegie Hall. She is a member of the Six Degrees Composers, and was a member of CUBE Contemporary Chamber Ensemble, where she was Co-Artistic Director for twenty years.

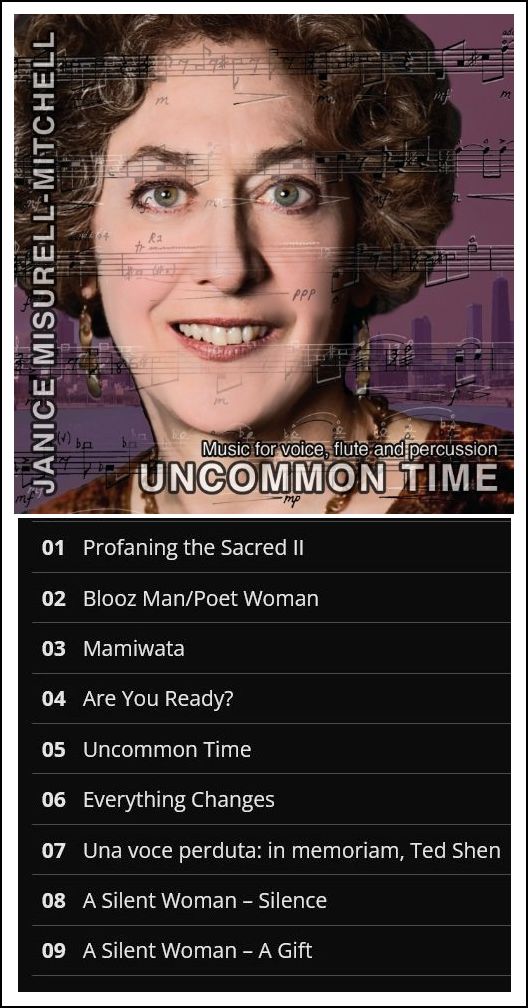

A composer of challenging music for flute, she has received commissions and awards from the National Flute Association for several of her solo pieces, described by Nicole Riner in The Flutist Quarterly: “…she imagines new ways of involving the flute in performance. It is a very specific style but it is done incredibly well.” Uncommon Time and Sometimes the City is Silent, for solo flute, both commissioned for the NFA High School Soloist Competitions, have been praised by teachers and students alike for their musical and practical approach to extended techniques. Recent pieces that incorporate text within the flute writing, such as Blooz Man/Poet Woman, and Profaning the Sacred II, flute/voice, are virtuosic works that have excited a wide range of audiences; Profaning the Sacred II was the winner of the 2009 New Genre Prize from the International Alliance for Women in Music. Her most recent piece, The Art of Noise, for flute and percussion, draws on a text by early 20th century futurist, Luigi Russolo, and has been widely performed.

Since the 1990s Ms. Misurell-Mitchell has been developing music combined with speech, theatre and dance; she has produced videos of these works as well. After the History, for voice/flute and percussion, presents views of war through a variety of musical perspectives. Scat/Rap Counterpoint, for voice and percussion, features nine different characters, played by the composer, who engage in rhyming dialogues on the state of the arts in the U.S.: “the evening’s showstopper,” writes the late Andrew Patner, music critic for the Chicago Sun-Times. Give Me an A! for voice/flute and Are You Ready? for solo voice, have transformed staid concert audiences into responsive jazz audiences. Her most recent work in this genre, Everything Changes, for flute/voice and percussion, received rave reviews from the audience at the international exhibition, ArtChicago.

She recently has expanded her area of vocal performance to works by other composers and writers: Berlin composer and pianist Stefan Litwin, Chicago composers Lawrence Axelrod and Patricia Morehead, and in presentations of poetry, both by contemporary poets and the Dadaists. She also has created music to be performed with readings by contemporary poets, such as Chicago’s Nina Corwin.

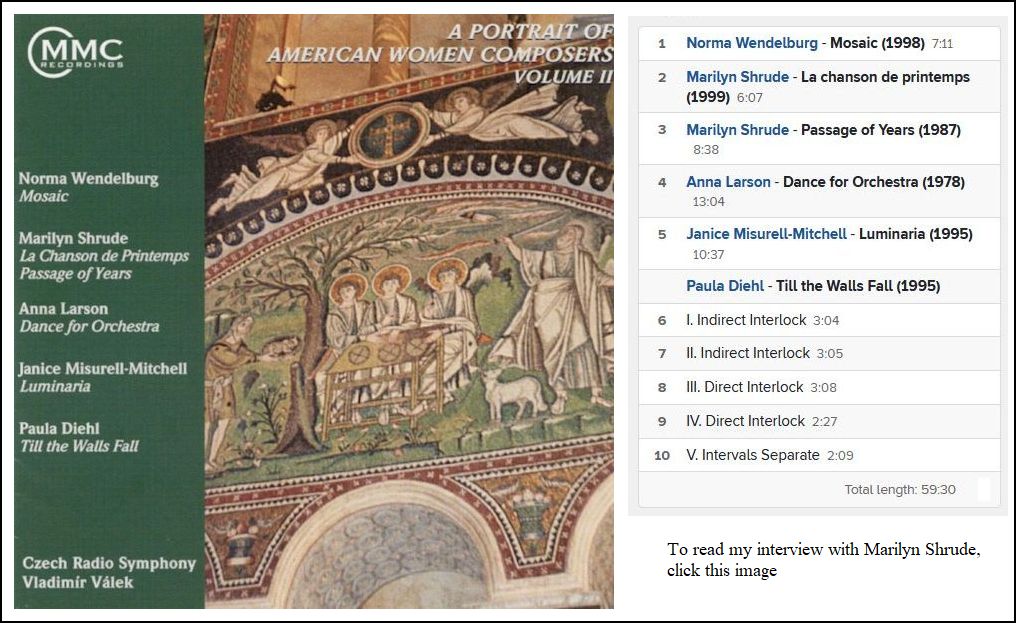

A composer of innovative works for larger ensembles as well, Misurell-Mitchell has created highly acclaimed pieces such as Luminaria, an orchestral work recorded by the Czech Radio Symphony, and Sermon of the Middle-Aged Revolutionary Spider, a musical monodrama for tenor, chamber ensemble and Gospel choir based on the poetry of Angela Jackson and written for the late world-renowned tenor William Brown.

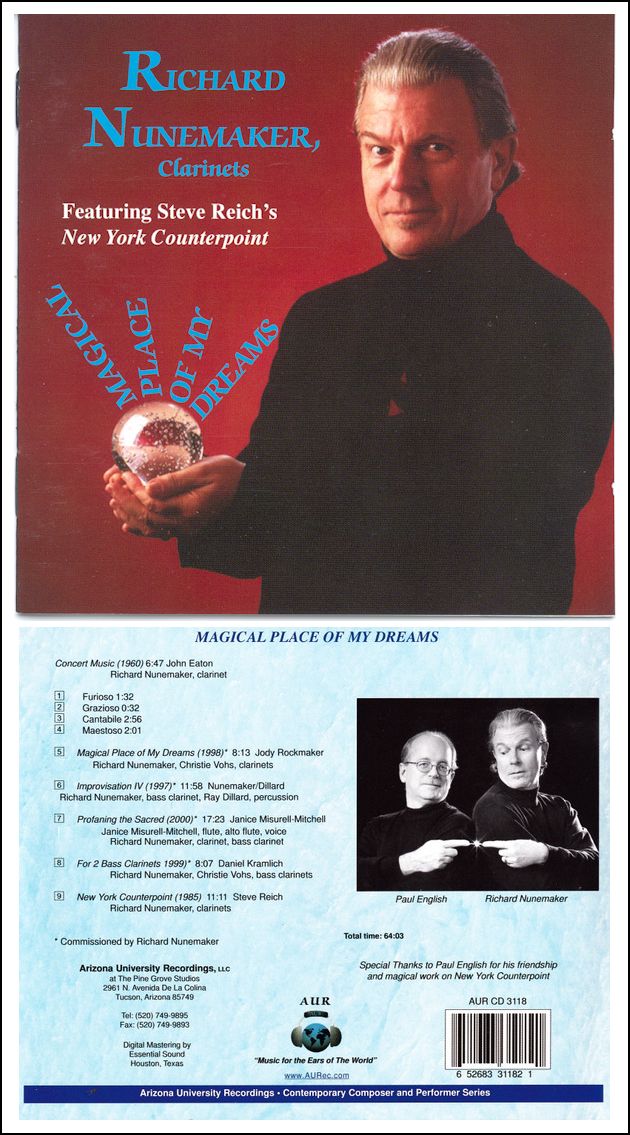

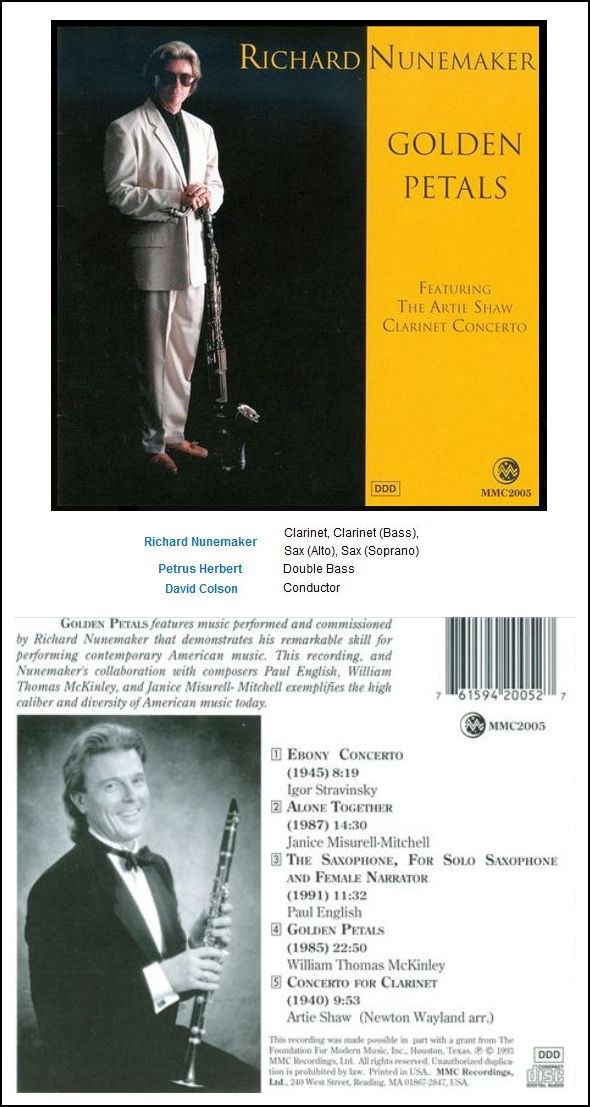

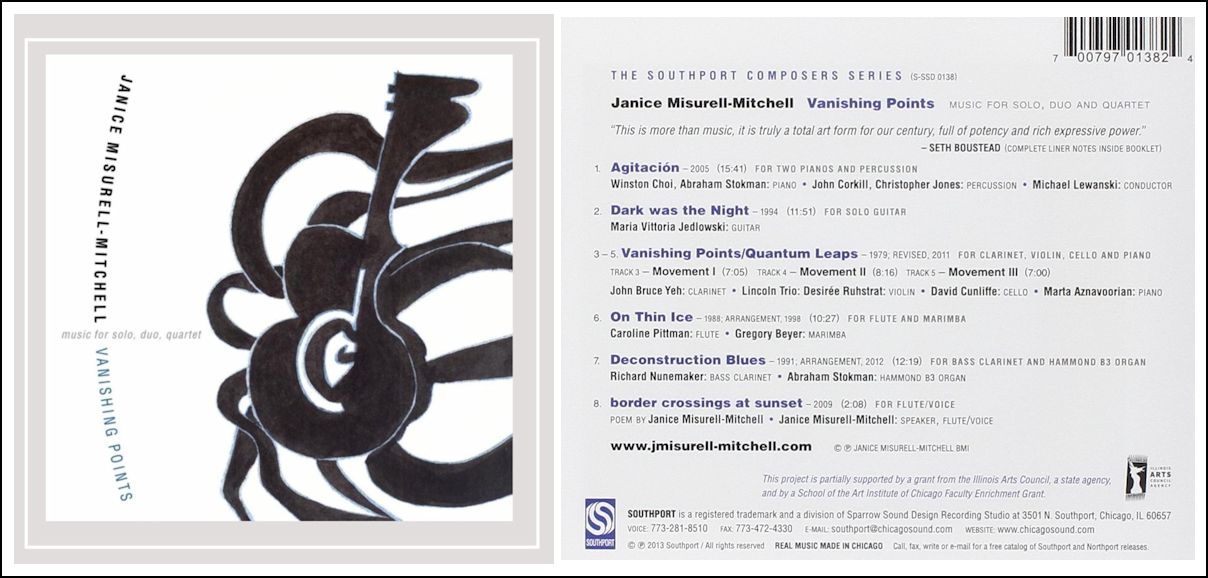

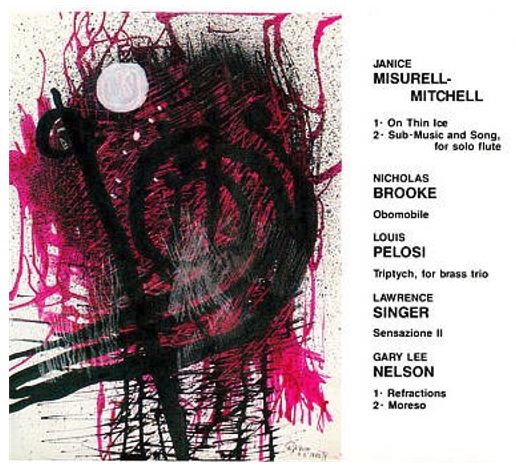

In 2010 she released the CD, Uncommon Time, a collection of her music for voice, flute and percussion, on Southport Records: “Misurell-Mitchell…cuts loose with this sometimes arresting, often outrageous, always entertaining collection of avant-gardish pieces for voices, flute and percussion. Her fearless channeling of the great Cathy Berberian in “Are You Ready?” has to be heard to be disbelieved”, John von Rhein, Chicago Tribune. Her most recent CD, Vanishing Points, music for solo, duo, quartet was chosen by Peter Margasak of The Chicago Reader as one of the top five new music recordings in “Our Favorite Music of 2013”. A rave review by Frank J. Oteri is online at NewMusicBox. Her solo recordings are on the Southport Label; others include MMC Recordings, OPUS ONE Recordings, Capstone Records, Arizona University Recordings and meerenai.com; her videos After the History, Scat/Rap Counterpoint, Sermon of the Spider and others are available on Youtube. https://www.jmisurell-mitchell.com

Misurell-Mitchell received degrees from Northwestern University, the Peabody Conservatory and Goucher College. Her primary teachers in composition were William Karlins, Ben Johnston, Stefan Grové and Robert Hall Lewis, and Bonnie Lake and James Pappoutsakis in flute. Additional study has been with Joanie Pallatto, vocal improvisation; Barbara Ann Martin, classical voice; workshops with Jaap Blonk, Lynn Book and Theo Beckman in vocal performance and improvisation; Bunky Green, jazz improvisation; Harvey Sollberger, contemporary flute; Ralph Shapey, conducting. Before teaching at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago she taught at DePaul University, Northwestern University, the University of Chicago, Roosevelt University, the American Conservatory of Music and Chicago State University.

BD: [With mock horror] You mean you swipe ideas

from other people???

BD: [With mock horror] You mean you swipe ideas

from other people??? BD: We have music, and we’re starting to get into virtual

music. At what time does it become non-music?

BD: We have music, and we’re starting to get into virtual

music. At what time does it become non-music?