|

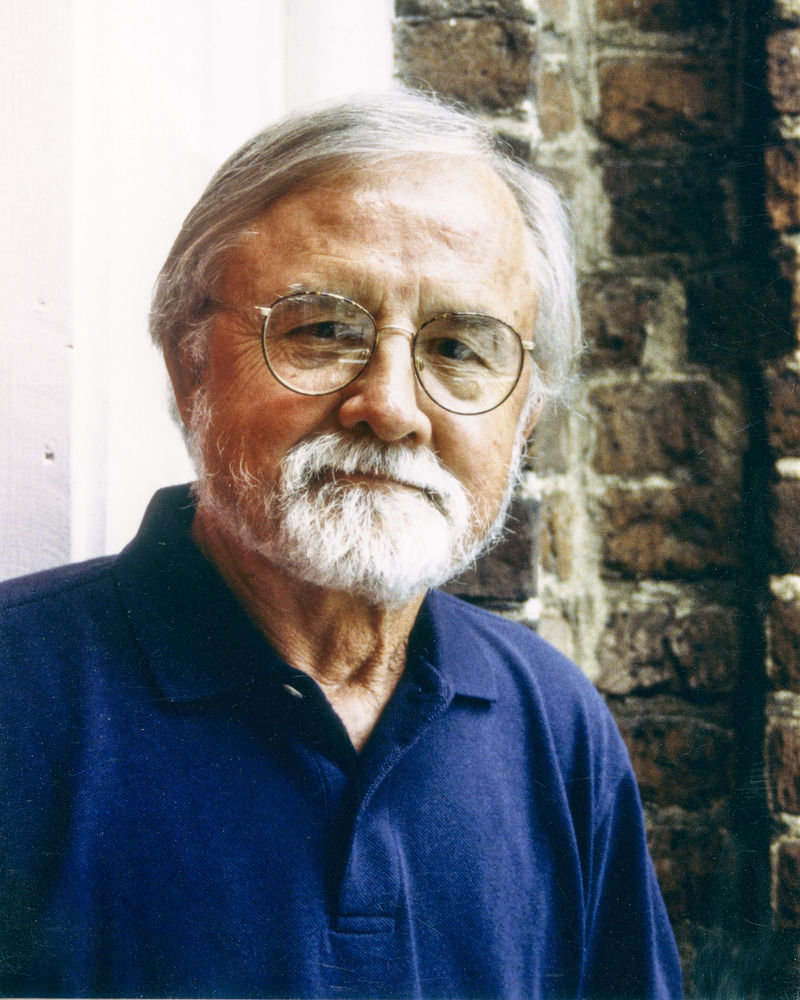

Richard Henry Moryl, musician,

composer, artist and university professor, was born in Newark, N.J.

on February 23, 1929. He died April 8, 2018 after coping with health

issues for several years. The son of Walter Moryl and Catherine Hozempa,

Richard received his undergraduate degree in clarinet performance from

Montclair State University in N.J. He went on to earn his master's degree

in composition at Columbia University, and did doctoral studies at Brandeis

University and the Hochschule fur Musik in Berlin. His teachers

included Frederick Breydert, Iain Hamilton, Boris Blacher,

and Arthur Berger.

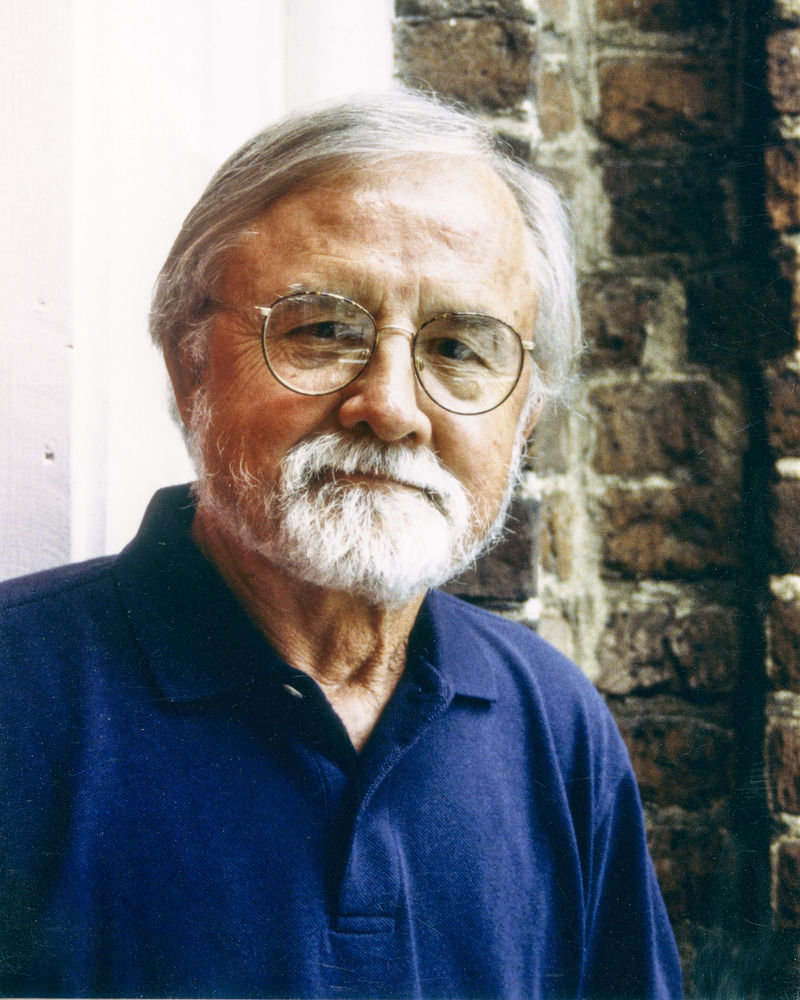

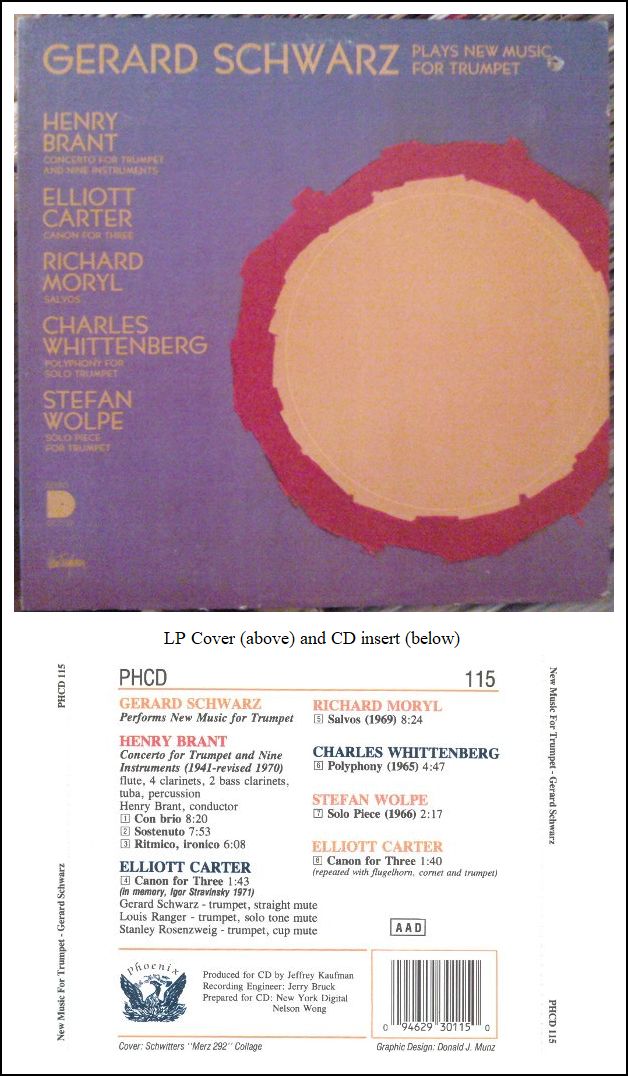

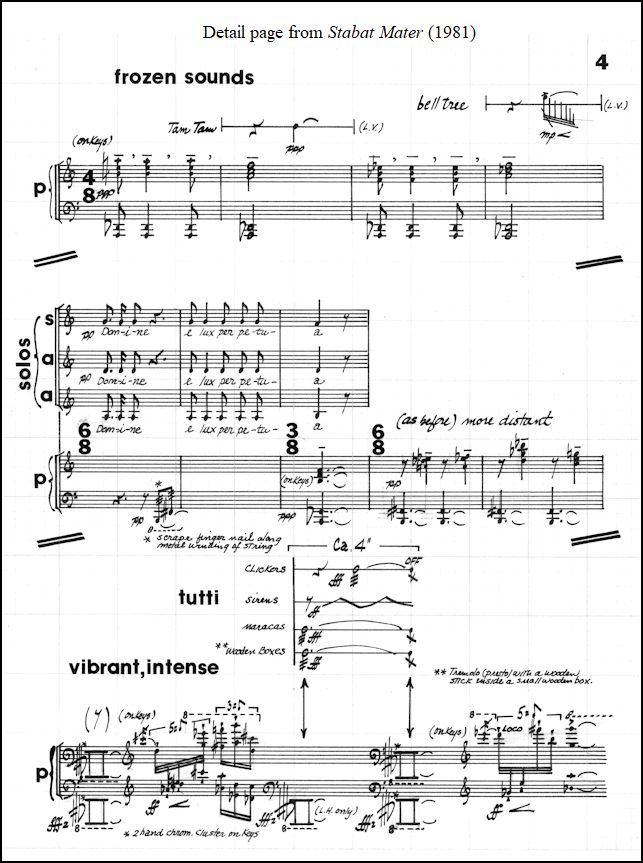

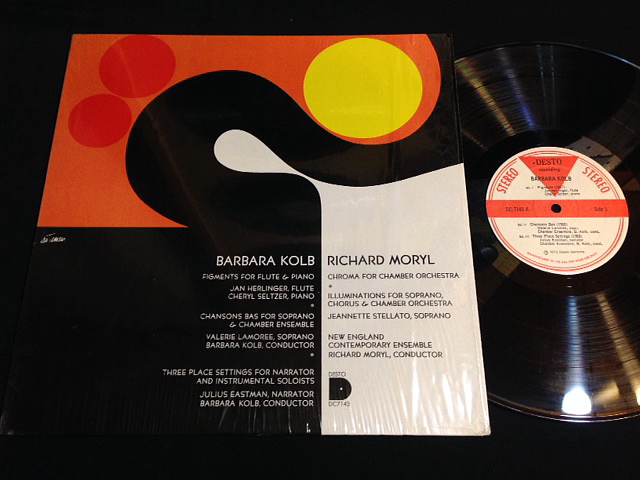

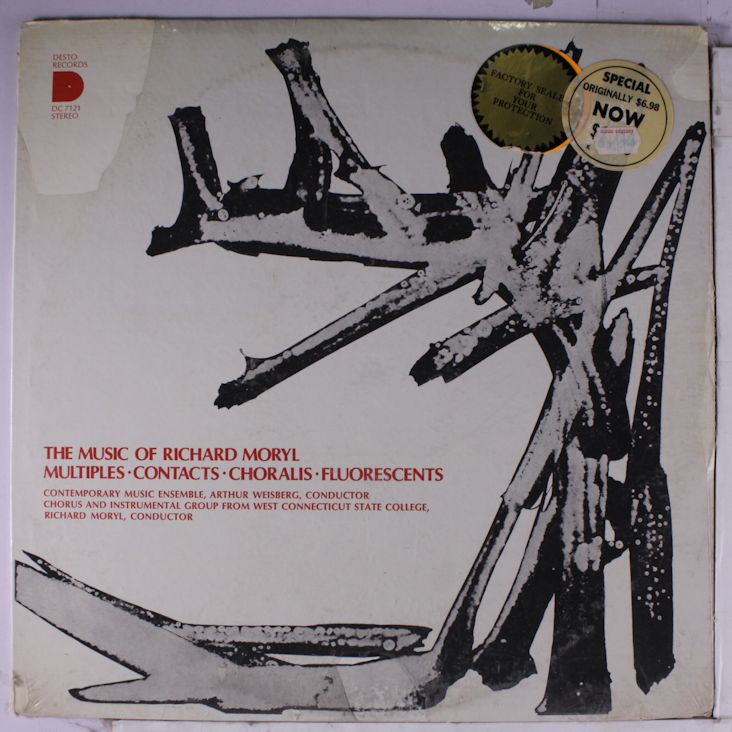

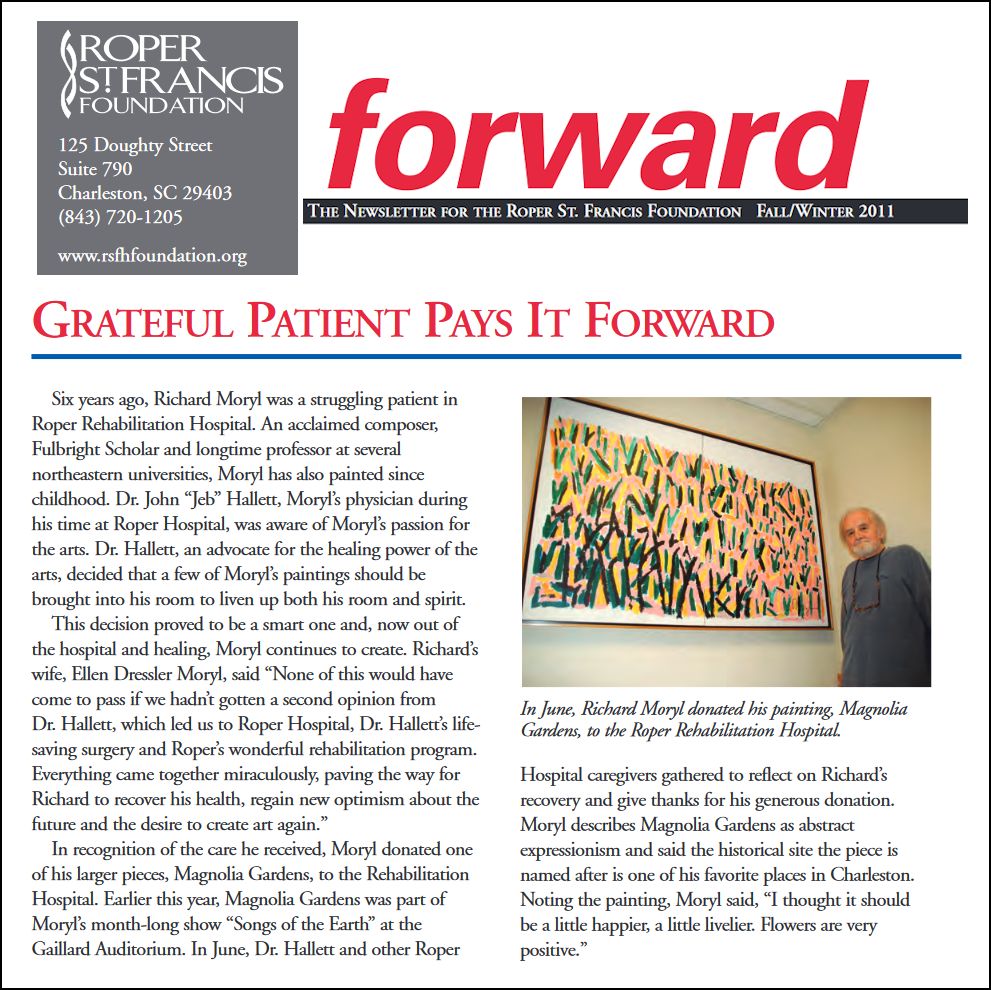

For three decades Moryl served as a music and composition professor at Western Connecticut State University in Danbury, CT, as well as the University of Connecticut and Smith College. As a composer, he received many awards and fellowships, including two National Endowment for the Arts awards, grants from the Ford and Martha Baird Rockefeller Foundations and many others. In 1963 he was a Fulbright scholar in Germany. Over 300 performances of his works have been given in Europe, the United States and South America. Richard Moryl was the founder and director of the Charles Ives Center for American Music (CICAM), which for over twenty years has performed and supported American composers and their music. More recently, (beginning in 1995) the CICAM was presented at the Piccolo Spoleto Festival for several years as part of the Spotlight Concert Series, continuing its mission of presenting works by American composers performed by local and regional musicians, the Charleston Symphony Orchestra and such notable groups as the New Jersey Percussion Ensemble and The St. Petersburg (Russia) String Quartet among others. Moryl was one of the international judges for the 2nd Annual Dmitri Shostakovich Chamber Music Competition in St. Petersburg, Russia in 1991. Forty of his works are published and ten have been recorded. Moryl founded and directed the New England Contemporary Music Ensemble which has performed extensively throughout the Northeast and the South, and which has been recorded on Desto and Serenus records. A CD of his piece, Das Lied (sung by Jan De Gaetani and conducted by Gerard Schwarz) was re-released in 2000 on the Opus 1 label. [The flip side of the original CRI LP contained a chamber work by Francis Thorne, conducted by Ralph Shapey.] In addition to his career as a composer and musician (clarinet, flute and saxophone), Moryl has been a prolific artist and photographer, creating a large body of work which spans a period of nearly 50 years. He has had numerous exhibits in Connecticut and other parts of the East Coast, and has had several of his works included in juried art exhibits in Charleston, SC. Moryl moved to Charleston in 1994 and married Ellen Dietz Dressler. Together they were the parents of several beautiful dogs, most recently Wolfgang and Grieg. In addition to his wife, Ellen Moryl, Richard is survived by his step-daughter, Michelle Dressler Lomano; step-grandchildren, Tristan Lomano and Cecilia Lomano; brother, Walter Moryl; sister, Arline Frances Durmer (James); and several nieces and nephews. Richard's family and friends are invited to attend his services in Mepkin Abbey at 1098 Mepkin Abbey Road, Moncks Corner, SC on April 21, 2018 at 2:00 p.m. Arrangements by J. Henry Stuhr, Inc., Downtown Chapel. In lieu of flowers, memorials may be made in Richard's name to Hallie Hill Animal Sanctuary at 5604 New Rd, Hollywood, SC 29449 or the Charleston Symphony Orchestra at 2133 N Hillside Dr, Charleston, SC 29407. == Published in Charleston

Post & Courier on April 15, 2018 (with additions)

== Names in this box (and below) refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

RM: Probably not. But you get a performance one

in a while, like my String Quartet, which was the last thing

that was recorded. I think they did a beautiful job, but

actually the first time they played it was the best it’s ever been played.

There was just a magic about things being in the right places

— the little things that aren’t written in the music.

For instance, a pause between the notes, or something like that.

RM: Probably not. But you get a performance one

in a while, like my String Quartet, which was the last thing

that was recorded. I think they did a beautiful job, but

actually the first time they played it was the best it’s ever been played.

There was just a magic about things being in the right places

— the little things that aren’t written in the music.

For instance, a pause between the notes, or something like that. RM: I don’t think it’s going to happen

anymore. The days of masterpieces are over. The last guys

who made it were Bartók, and maybe Shostakovich. I love Shostakovich.

He’s a very fine composer, and I know the Manhattan String Quartet has

just discovered his String Quartets, and they’ve done them all now.

They’re doing them in the Town Hall next year. But I really think

the world is much too eclectic. Computers have taken information

and chopped it into little pieces. Everybody’s a specialist in

some very narrow range, so I don’t think any style of music now would

appeal to a large group the way it did in the Baroque period. You

may have had the Italian Baroque, and you may have had some German Baroque,

and Handel doing something else in England, but there was a certain agreement

on musical vocabulary. We started to lose that in the Nineteenth

Century with the Romantic composers. By the end of the Nineteenth

Century, it’s amazing who was alive at the same time —

everybody from Brahms to Debussy to Mahler and Bruckner. The

list is amazing. I checked it out one time for my class, and we

couldn’t believe who was living in the last twenty-five years of the Nineteenth

Century. [Both laugh] Everyone who was anyone was living then,

and once we hit the Twentieth Century, we saw the social changes

— the ‘isms’, like communism, socialism, and everything

else. The artist is a pawn of all of this. We opened up there

for a while in the ’60s and ’70s,

but...

RM: I don’t think it’s going to happen

anymore. The days of masterpieces are over. The last guys

who made it were Bartók, and maybe Shostakovich. I love Shostakovich.

He’s a very fine composer, and I know the Manhattan String Quartet has

just discovered his String Quartets, and they’ve done them all now.

They’re doing them in the Town Hall next year. But I really think

the world is much too eclectic. Computers have taken information

and chopped it into little pieces. Everybody’s a specialist in

some very narrow range, so I don’t think any style of music now would

appeal to a large group the way it did in the Baroque period. You

may have had the Italian Baroque, and you may have had some German Baroque,

and Handel doing something else in England, but there was a certain agreement

on musical vocabulary. We started to lose that in the Nineteenth

Century with the Romantic composers. By the end of the Nineteenth

Century, it’s amazing who was alive at the same time —

everybody from Brahms to Debussy to Mahler and Bruckner. The

list is amazing. I checked it out one time for my class, and we

couldn’t believe who was living in the last twenty-five years of the Nineteenth

Century. [Both laugh] Everyone who was anyone was living then,

and once we hit the Twentieth Century, we saw the social changes

— the ‘isms’, like communism, socialism, and everything

else. The artist is a pawn of all of this. We opened up there

for a while in the ’60s and ’70s,

but... BD: Let me ask another balance question.

In your music, or music in general, where is — or

where should be — the balance between the

artistic achievement and an entertainment value?

BD: Let me ask another balance question.

In your music, or music in general, where is — or

where should be — the balance between the

artistic achievement and an entertainment value? BD: Should we continue to write Beethoven’s

Ninth, or are we up to Beethoven’s Twenty-third by now?

BD: Should we continue to write Beethoven’s

Ninth, or are we up to Beethoven’s Twenty-third by now? BD: So if you didn’t have Gerard Schwarz to work with,

you might have put in something that was truly impossible?

BD: So if you didn’t have Gerard Schwarz to work with,

you might have put in something that was truly impossible? BD: Is that’s what separates a masterpiece

— that it can be destroyed and still survive?

BD: Is that’s what separates a masterpiece

— that it can be destroyed and still survive? BD: Is composing fun?

BD: Is composing fun?

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on October 1, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following February, and again in 1994 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2018, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.