Contrabassoonist Susan Nigro

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

In the course of doing over 1600 interviews, most of

my guests are people I have known of and respected, or are up-and-comings

in the world of Classical Music. A select few are people who remain

in my circle over many years, and I'm pleased to say that Susan Nigro [pronounced

NYE-gro] is one of those special friends.

Both of us grew up and have spent our lives in the Chicago

area, but our particular bond is that of a common instrument - the lowest

member of the double-reed family. We even had the same teacher, Wilbur Simpson of the

Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He actually began there as the Contrabassoonist

and soon switched to Second Bassoon where he remained for 45 years.

In high school, I played bassoon, then went away to undergraduate school.

When I returned to do my Master's Degree in Music History back at Northwestern,

I needed to continue with an instrument, so I called Wilbur and asked if

he'd be willing to let me play contrabassoon. He was amused and delighted,

and we found an old French instrument for me to honk on. We had a

blast together, and he often spoke of Sue Nigro, who was more into the contra

than anyone he'd ever seen or heard of. He was pleased at her progress,

and actually believed she would make a major mark with this unwieldy monster.

I stayed in touch with Wilbur during my radio career - even finding an excuse

to interview him during the 100th season of the CSO - and he always mentioned

Sue and how pleased he was with her burgeoning career.

I, too, was pleased for her, and as she started to make

recordings, I was able to promote her properly on my programs. Needless

to say, an interview was set up and we met as old friends in 1997 for our

chat. She has a unique mixture of seriousness and playfulness, but

when speaking about her passion, she was all business. This was her

cause, and she was absolutely devoted to it. Now, more than ten years

later, she has several recordings out and a website [www.bigbassoon.com] which

lists her accomplishments and future engagements.

I still see her sometimes at regular concerts of the

CSO, and phone messages and e-mails continue as we both push forward with

our lives. It's a special pleasure, now, to have our formal conversation

transcribed and posted on my own website.

Here is what we said that afternoon . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You call yourself "the contrabassoonist with a cause."

What, exactly, is the cause?

Susan Nigro: The cause is to get people to listen to the contrabassoon

as a solo instrument, try to give it some respect, and at least give it a

chance to be heard. I sort of view the contrabassoon in the same light

as Rodney Dangerfield: it doesn't get any respect,

and I'm just trying, in my own way, to do something to try and help it out

a little bit because I feel it's a beautiful instrument. It has a

nice sound and people should listen to it.

BD: Why does no one listen to it, ordinarily?

BD: So

you are trying to present it in a different light?

SN: That's the main thing I've been doing. I've

been trying to give recitals on it so people get a chance to hear it in a

solo context and not just in the orchestra. Most of the time when it's

in the orchestra you really can't hear it too well. What they call

a solo in the orchestra, in something like Ravel's Mother Goose suite or the Left Hand Concerto, is a little short

thing. Two or three minutes later it's over and that's it.

BD: So it's more of an effect.

SN: Yes, it is, and it can be very expressive.

The contrabassoon has a very nice sound and it's got a lot of technical capabilities

that people don't realize. It's not quite as

clunky as a tuba - and I don't mean any disrespect by that - but in terms

of having valves. I think the contra has more of a fluid personality,

almost like a string bass in terms of being able to play technical things

and making them sound well, and getting around nicely.

BD: And yet there are not too many people who would go

to a string bass recital, although there are some professional string bassists

who do go around!

SN: Sure, like Gary Karr, for example,

who is a wonderful artist.

BD: When he comes to town, do the two of you get together

and commiserate?

SN: [Chuckles] Actually,

believe it or not, I have corresponded with him, but I've never had the opportunity

to meet him. I'd like to do that someday.

BD: Are contrabassoonists nice gals and nice fellows?

SN: Oh, contrabassoon players are wonderful people. They're usually pretty laid back and friendly, and

non-stressed. They just seem to have something of a party personality.

BD: [Chuckles] Well, the bassoon

is called the clown of the orchestra. Is the contrabassoon the contra-clown,

or the big clown?

SN: I suppose. In one way it helped me with one

of my hobbies, which is musical jokes. It wasn't

that the instrument itself was so funny, but when you play the contrabassoon

you don't play all the time. You have a lot of free time, time off

that you're not playing, so it gives you time to do other things like collect

jokes, or swap humor with other people. So that

could be part of it.

BD: I see. So you're making

a whole long list of contrabassoon jokes?

SN: The jokes aren't just about contrabassoons; they're

about anything having to do with music, or conductors, or orchestras, but

just the fact that you have a lot of free time, you have more time to collect

jokes and talk to people. Contrabassoon players are hobbyists just

by nature. Most contrabassoon players I know have

got at least one or two hobbies that they really avidly pursue, simply because

they have the time to do it.

*

* * *

*

BD: You

play both bassoon and contrabassoon. Is there a big difference in

playing the two instruments?

SN: Not a big difference. If

you play the bassoon, you can get around on the contrabassoon to a certain

extent. There are a few things that you need

to use - a bigger reed, of course, which uses more air, and the biggest

difference would be in terms of the fingering. Without

getting too technical about it, the octave key mechanism on the bassoon and

the contrabassoon is exactly the opposite. On

the bassoon, we have what we call a whisper key; you press down to go into

the lower register of the instrument. Because

it covers up the little hole at the top, you play the lower notes. The contrabassoon operates more along the lines of

a saxophone or an oboe, in that it has two octave keys, and you press one

to go up, not to go down. So it takes a little

getting used to, especially when you're doubling, like in a Mahler symphony

where you're on third or fourth bassoon and contra, you've got to take a

minute and straighten out your thoughts when you're switching instruments,

otherwise you're likely to make a mistake. You really have to think

about what you're doing. You really do. And, of course, the embouchure is a little different,

and there are minor things like that, but the main thing is the octave key

mechanism, which is exactly the opposite.

BD: So it's more than just going from the violin to the

viola, and stretching out.

SN: Oh, yes. It is a bigger

reach, and the upper register fingerings on the contrabassoon are completely

different than on the regular bassoon.

BD: Why is that?

SN: Because it has more harmonics. Some of the

lower notes are different, too, because we add extra keys on the contrabassoon

to increase the resonance of low notes, which you don't do on the regular

bassoon, or "the little bassoon," as we call it. [Both chuckle]

There are a few isolated notes that have exactly the same fingerings, but

not very many. So it's not a huge complicated

issue; it just takes a little to get used to.

BD: Do you really think of it as "the little bassoon,"

even though the regular bassoon is nine feet of tubing? How long is

the contrabassoon?

SN: It's exactly twice as long. It's eighteen feet,

four inches. Those of us who consider ourselves primarily contrabassoonists

would think of the regular bassoon as "the little bassoon". Most regular

bassoon players who play primarily bassoon, think of the contrabassoon

as "the big bassoon." It's just what's normal to you, and what's

normal to me, of course, is the contrabassoon, so the regular bassoon is

a "little bassoon", or a "tenor bassoon".

BD: And the oboe is a descant bassoon?

SN: [Chuckles] We think of

it as the soprano member of the contrabassoon family.

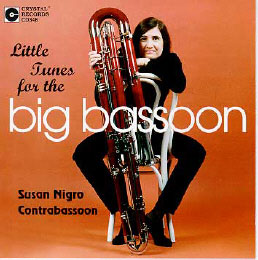

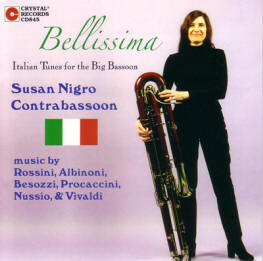

BD: [Laughs] Now your first

record is called "The Big Bassoon". Are you proud to have it called

that?

SN: I am, but it wasn't my idea.

It was suggested by Peter Christ, who heads up Crystal Records. When he first suggested it to me, I was sort of turned

off, as a matter of fact, because I wanted to have the name "contrabassoon"

in the title of the recording. But he explained

to me that a couple of years prior to that, they had issued a recording by

a bass trombonist and had called it "The Big Trombone", and apparently it

had generated a lot of sales and a lot of interest. They had a picture

of him with this big instrument on the front cover and Peter really thought

it was a very good selling point. So he thought

"The Big Bassoon" might be more intriguing, whereas if somebody heard the

title "Contrabassoon," they wouldn't even bother to look any further; they're

not interested. "What's a big bassoon?" That's sort of intriguing. So

instead of just passing it by, they look at it to see, "Is it a regular bassoon,

or is it a contrabassoon, or what is it?", and then maybe they would just

have enough interest to pick it up.

BD: Is it a joke, or is it really a real instrument?

SN: Yes! Exactly. Exactly. So then on the

second CD that's coming out we decided to play that for all it's worth, and

call the second one "Little Tunes for the Big Bassoon" because it's all

shorter works, and of course it's still played on this big bassoon - the

contrabassoon - so we decided to hang on to it. And it worked.

SN: Yes! Exactly. Exactly. So then on the

second CD that's coming out we decided to play that for all it's worth, and

call the second one "Little Tunes for the Big Bassoon" because it's all

shorter works, and of course it's still played on this big bassoon - the

contrabassoon - so we decided to hang on to it. And it worked.

BD: Has the contrabassoon been standardized so that one

contrabassoon is like another contrabassoon?

SN: Not to the extent that the bassoon has, but pretty

much, yes. I could pick up another contrabassoon that's different from

my own and play it pretty well, but there are some differences - small differences

- in terms of the shapes of the keys. We have an ancillary E-flat

key for the middle E-flat on the instrument. We can't play a forked

E-flat like the regular bassoon does. It doesn't work on the contra,

so you have to have an extra key which could either be with the ring finger

or with the right thumb, or sometimes with the right hand first finger,

just depending on which instrument you have. So there are minor differences

like that. Some of the contrabassoons don't have

both F-sharps, like the regular bassoon has, and the octave key mechanisms

vary a little bit from one instrument to the other.

BD: Now this, of course, is all with the standard German

fingering system.

SN: Yes, and of course the Buffet contrabassoon is like

the Buffet little bassoon, so it has French fingering.

I haven't had much direct experience with that other system.

BD: Are you glad that the instrument you use has the bell

folded down so that it doesn't stick way up like the French models?

SN: Yes, because you get complaints from the people that

sit behind you when you play the big tall one. I

have played those and they're hard to balance. I always feel like

they're top-heavy and they're about ready to tip over.

There's a great deal of weight on your left arm just trying to support

it. And then you've always got complaints from

behind you, "Uh, could you move to the left or to

the right? I can't see the conductor." So it does get to be rather annoying after a while. This shorter, more folded-over one they call the

"opera model", because it was for use in the opera pit. It is a lot

more convenient in terms of not annoying other players, and it's also easier

to play in terms of the balance and the weight.

BD: Here comes another brass player joke, then.

They should say, "Can you please move, I can still see the conductor." [Both

laugh]

*

* * *

*

BD: You're encouraging people to write solos for the contrabassoon. Are you also encouraging them to write better parts

for the contrabassoon in orchestral literature?

SN: If I were in a position to do so, I would. I

don't have a real wide influence at this point. I

worked with several composers in writing solo works for the contra.

Certainly, if they would write an orchestral piece I would try my very

best to get them to include a contra part, and to make it sure it was a

good one, not just one of these "throwaway" parts where you're doubling

the cellos, or doubling the tuba, not heard at all. That doesn't make any sense. I always think that

Brahms had the right idea in his symphonies. He used either the contrabassoon

or the tuba. The contrabassoon is in Symphonies

1, 3, and 4; the tuba plays in Symphony no. 2. We

don't get in each other's way. He did use both instruments in the

Academic Festival Overture, but they're independent of each other. They very rarely

play the same notes or the same line, so he was real intelligent about

that. Mahler also had ideas in that direction. My favorite Mahler symphony is number 4, because it

doesn't have a tuba. It's more of a chamber work and the contra can

be heard. But even in the bigger works where you

have both instruments, tuba and the contra, he seems to keep them out of

each other's way so the different timbres can be heard. He also uses

them in different functions from each other.

BD: So he was really a sympathetic composer.

SN: Yes, I think so. Many

composers that write parts for the contra, no matter how well-intended

they are, just throw it in with everything else and let it double what somebody

else is already doing. That really doesn't do a whole lot of good.

BD: It doesn't make for a meatier sound down there at

the bottom?

SN: They think it does. I don't know. I'm

quite convinced that if the whole brass section is blowing away at a big

forte, you probably can't hear the contrabassoon at all.

I doubt very seriously that you could. It might add something

to the overall timbre, but you just really can't hear it very much.

BD: But if you take it away, wouldn't it lighten the sound

a bit?

SN: Perhaps, perhaps. But

it is sort of frustrating to be sitting there and blowing at a double or

triple forte, and just being covered up by everybody else sitting around

you. It's just not very rewarding to have that happen.

BD: So that's why you're trying to get solos written

for you?

SN: I'm trying to get solos written for it, because even

when they do write for it in the orchestra, a lot of times it does

wind up being buried, unless it's a chamber orchestra piece like the Dvořák

Serenade for Winds, for example.

That's very nice because the contrabassoon can be heard; or the Mozart Serenade for 13 Winds, if they let

it be played by a contra rather than giving it to the string bass, as so

many people do. That's also very nice because

it's an independent part and you don't have somebody competing with you in

the same register. Not that I'm not a cooperative

type and don't want to share things, but what's the point of writing for

an instrument if nobody can hear it?

BD: When you ask someone to write you a piece, do you

give them any more parameters than just, "Write me a piece"?

SN: No. I would talk to them about the instrument

and give them some recordings of things that I've done, so they get a chance

to hear it. Of course, you're usually approaching a sympathetic soul

in the first place, either a bassoon player, or somebody who knows a bassoon

player, or somebody who's really into woodwinds. You talk to them a

little bit and get them used to the idea about writing a solo for the instrument. It isn't something that they agree to right away,

so you have them come and hear you play, or you give them a tape so they

get the sound of the instrument in their ear. Then, of course, they

have a lot of questions such as, "What is the range

of the instrument? What can it do in terms of

dynamics? Can it play fast notes?" I will

work with the composer. Lots of times they will

send me a sketch of something they've written. I'll

look at it and I'll play it through and make some comments - not from a compositional

standpoint, but just in terms of playability. Sometimes

I'll even throw a cassette on the machine and play for them what they've

written to let them hear how it sounds on the instrument so they can tell

if it works or doesn't work, not from a compositional standpoint, but just

from a practical performance standpoint. They

don't want to write something that's unplayable, or something that doesn't

sound good. I've worked with two or three composers that way, who've

been real nice to take my suggestions and allow me to help them that way. But it's still their piece. I'm in no way a

composer, and I know my limitations.

BD: Sure, but your experience as a player can help them

out.

SN: Absolutely. The contrabassoon is not an instrument

that people know as well as the other ones. They don't teach it in

the composition classes - at least not in terms of soloistic capabilities

- and people just really don't know what it can and cannot do.

BD: Maybe that's who you should be contacting - the composition

teachers and the theoricians - to put in a plug for the contrabassoon right

at the top.

SN: I've tried as much as I can. When one of the

smaller orchestras I play with around town is premiering a work, I will almost

always talk to that composer afterwards and say, "You wrote a really nice

contrabassoon part in this piece and I really enjoy it.

Would you like to think about writing a solo for the contra?"

Sometimes they're receptive, and sometimes they're not, so you just have

to go about it that way and try to sell yourself without really hitting 'em

over the head, because most people, quite frankly, have never thought of

writing a solo for the instrument.

BD: But if they wrote a poor part for it, will you tell

them that it could've been a little more interesting, or that it was just

a boring part?

SN: I try to be diplomatic about these things, and try

to find some of what they did that was good and bring that out first.

"I wish you could've made more of that, or maybe given it a little bit more

to do," or, "You had a really good idea but it doesn't work well on this

particular instrument." I try real hard not to come down on any composer

in any way, because I want to encourage them, not discourage them. I don't want them to think of me as an unpleasant

person who's going to be real judgmental if they try to write something

for me. I want to try to be helpful and try to

be upbeat and be encouraging to them.

*

* * *

*

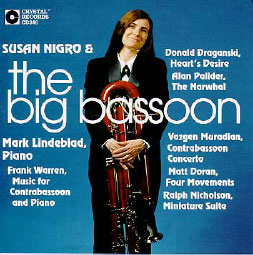

BD: I assume that quite a bit of the material you play

was not originally written for the contrabassoon.

SN: That's true.

I do a lot of transcriptions. The first

CD I had out - "The Big Bassoon" - all those pieces were written for me,

so that was sort of an exception. The pieces

that are going to be on my second CD mostly are transcriptions that were written

for either the bassoon or for some other instrument that have been transcribed,

or I simply sat down and read off the original music.

Three pieces were written for alto sax! It's very easy. You just change the clef and change the key signature

and you play it! It's not a big deal. So it works well. Bassoon

music, of course, works well too.

SN: That's true.

I do a lot of transcriptions. The first

CD I had out - "The Big Bassoon" - all those pieces were written for me,

so that was sort of an exception. The pieces

that are going to be on my second CD mostly are transcriptions that were written

for either the bassoon or for some other instrument that have been transcribed,

or I simply sat down and read off the original music.

Three pieces were written for alto sax! It's very easy. You just change the clef and change the key signature

and you play it! It's not a big deal. So it works well. Bassoon

music, of course, works well too.

BD: Have you tried playing a Vivaldi piccolo concerto

or something like that just for effect? [Vis-à-vis the recording

shown at right, see my interview with Frank Warren.]

SN: I haven't done that yet, but I've got some Vivaldi

bassoon concertos that I've done, which I enjoy very much. Right now

I'm taking a real hard at look at some flute music that was written by Bach.

I'm thinking about doing an all-Bach program one of these days, so if I can

make that work I sure will.

BD: [Half tongue-in-cheek] Bach

on the contrabassoon!

SN: Yes, why not? If he had

known what it could do, he probably would've given it a chance. But

he was a composer, of course, that predated the instrument. Well,

I don't know if he predated it or not, because Handel wrote for it, but in

the field that Bach was writing - church music and cantatas - he wouldn't

have had any use for it. So I can't really fault him for not using

it. And the instrument they had back then was

not very well developed, it wasn't very refined. It didn't have very

many technical capabilities. I always marvel at

the Vivaldi bassoon concerti knowing the instrument they had back then.

There were only nine or ten keys on the instrument, and for those people to

be able to execute difficult music like that with a severely limited keywork

capability was amazing.

BD: Very much like the valveless horns and trumpets!

SN: Yes! Sure. What they did was amazing.

BD: When did the bassoon and then the contrabassoon come

into what we now would recognize as being standardized?

SN: I would say probably the early-to-mid-1800s. By the late Classical or early Romantic period it's

pretty much the way it is now.

BD: Did they progress together, or was it first the bassoon

and then the contra?

SN: The bassoon first, and then the contra. The contra really isn't as well developed as the bassoon. It's as far as it's going to get, but it hasn't got

the huge number of keys that the bassoon has, and all the alternate fingerings

that the bassoon has, because most people feel it doesn't need to have all

the technical capabilities because it doesn't have to do that as often. The orchestra parts for the contrabassoon are, by

and large, much simpler than they are for the regular bassoon, or the little

bassoon. They're playing bass lines or they're

doubling the cello part. Once in a while you'll get a melodic line,

but it's not usually terribly difficult. I don't mean that in a bad

way, but people who make the instrument saw that it didn't really need to

have all the bells and whistles that the regular bassoon had, so they just

haven't done it. The Fox bassoon company in this

country has made some advances. They put some rollers on the instrument

and they've given you a couple different options in terms of octave keys,

and that special E-flat key we talked about before.

But there's no contrabassoon in the world that has both A-flat keys

that the bassoon has. I guess people just realize

that they don't need it, so they don't make it.

BD: Would you like to have it?

SN: Oh, sure, because it gives you more opportunities

to use different fingerings, depending on what key you're playing in. Not that you use it all the time, but it comes in

handy.

BD: Have you had your instrument modified at all?

SN: I ordered an instrument to be built,

and I specified the keywork that I wanted to have on it.

My contrabassoon was built back in 1977. It's going to have

a birthday, and be twenty years old in May.

I made a whole list of things that I wanted them to do, most of which they

could. Some things they didn't offer as options,

so, obviously, I couldn't have them, but I have some extra trill keys, and

some extra rollers that I had built on to it. That

was not with the idea that I would be doing anything like I am now.

Twenty years ago I had no idea, but I just wanted to have as many options

on there as I could have to increase my technical capacity.

SN: I ordered an instrument to be built,

and I specified the keywork that I wanted to have on it.

My contrabassoon was built back in 1977. It's going to have

a birthday, and be twenty years old in May.

I made a whole list of things that I wanted them to do, most of which they

could. Some things they didn't offer as options,

so, obviously, I couldn't have them, but I have some extra trill keys, and

some extra rollers that I had built on to it. That

was not with the idea that I would be doing anything like I am now.

Twenty years ago I had no idea, but I just wanted to have as many options

on there as I could have to increase my technical capacity.

BD: Then do you modify it little by little every year,

or every five years?

SN: I had some work done on the octave keys a couple

years ago. I had them made larger and also moved down a little bit

- not actually for a technical reason, but I was having trouble with some

tendonitis in my left thumb. I realized it was

because I was having to stretch, a real big stretch, a big reach to get to

the octave keys, and I had developed a real problem in my left thumb as a

result. So they lengthened the two octave keys and moved them a little

bit lower to make it easier to play. So you can

have them do things like that if you want and they'll do what they can to

accommodate you.

BD: They should make the Sue Nigro

model contrabassoon.

SN: [Chuckles] It'd be nice,

but I don't see it happening.

BD: You don't need to mention names, but are there any

others who are trying to make it as a solo contrabassoonist?

SN: There's a young lady in South America [Mónica

Fucci of Buenos Aires] who plays in one of the orchestras down there

and has done several concertos with that orchestra. And I know that there are people in this country,

too, who have also done concertos. For example, the Gunther Schuller Contrabassoon Concerto was premiered in

1978 by Lewis Lipnick, the contrabassoonist in the Washington, D.C. orchestra.

It was written for him. He commissioned it and premiered it, and it

was played a couple years later by the contrabassoon player in Pittsburgh.

Donald Erb has written

a concerto for Gregg Henegar, the contrabassoon player who's in Boston now,

but previously was in Houston, and that's where he premiered it in 1984. So there have been some other players who have done

some works. I don't know if anybody is crazy

to do it to the extent that I have. I've done more or less the recital

route rather than the orchestra route, if for no other reason that I'm not

a full-time member of any orchestra. I'm a freelance

player around Chicago, and I play with some of the smaller orchestras.

If I can talk them into letting me do a concerto, I certainly will, but

that doesn't often happen, so my only choice is to do recital work instead.

BD: But you also play with the Chicago Symphony when they

need you.

SN: Yes. They joke about putting

me on pension. I've been a substitute with them for 22 years! [Laughter] So at least

I've got some longevity down there, but I'm not a full-time performer, so

I don't feel like I'm in a position with them, or any of the other groups,

to really insist upon any type of a solo thing. I

can offer it to them and I can tell them what I've got available, and if

they want me to do it, that's terrific, but...

BD: ...but it gives you the cachet that you are on that

level to be able to perform with them on a regular basis.

SN: [Modestly] I suppose that's

true...

BD: Does that give you a good feeling as far as your professional

standing?

SN: Oh, of course!

Sure it does. It really does, and it helps

you to keep your standards up, too. When you play with fine musicians

all the time like that, you always play better. It's contagious. I had a really nice opportunity about two years ago.

It was in the spring of 1995 that I got to do the Gunther Schuller Contrabassoon Concerto with the Omaha

Symphony and Maestro Schuller conducting. Talk

about standards, having the composer right on the podium conducting while

you play. That was a wonderful opportunity for me, and I enjoyed that

very much.

SN: Oh, of course!

Sure it does. It really does, and it helps

you to keep your standards up, too. When you play with fine musicians

all the time like that, you always play better. It's contagious. I had a really nice opportunity about two years ago.

It was in the spring of 1995 that I got to do the Gunther Schuller Contrabassoon Concerto with the Omaha

Symphony and Maestro Schuller conducting. Talk

about standards, having the composer right on the podium conducting while

you play. That was a wonderful opportunity for me, and I enjoyed that

very much.

BD: Was he pleased with you? [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown at left, see my interview with Burrill Phillips.]

SN: I think so. He's not one

that really puts a lot of accolades on people. He'll tell you if there's

something he doesn't like, there's no question about that, and if he doesn't

say too much, then that usually means that he's satisfied.

BD: Were you able to find something in there and show

him an even better way, or some extra brilliance in one of his parts?

SN: We talked a little bit about the cadenza in a couple

of the movements and different ideas about how it should be played.

He pretty much let me do it the way I wanted, so that was a good thing. He did the slow movement very, very slowly, so I had

to work out my breathing to be a little different than I had originally planned. But these were things that were pretty much a cooperative

effort between the two of us, and I felt that it was a learning experience

for us both. I don't mean that I could teach him anything about composition,

but just in terms of the instrument and in terms of the way it's played.

BD: You don't do any kind of circular breathing, do you?

SN: No, I've never done that. I did study with Arnold

Jacobs for about three years just in order to be able to use my air capacity

to its peak, so I feel like I've got a pretty good command over my four and

a half liters. It's hard when you have a really high-flow-rate instrument. It's easier, for example, with an oboe, where you're

just letting small amounts of air out at a time. You can sort of keep

that going with however they do it with their cheeks, and sort of breathe

in through your nose while you're letting it out through your mouth.

But when you've got an instrument like the contrabassoon or the tuba where

these huge quantities are passing through, I just think it's a lot less

practical. It's not as easy to do.

BD: Do you need as much air for the contrabassoon as for

the tuba?

SN: Not as much as for the tuba, but certainly more than

you would need for the little bassoon. Actually, the bassoon and

the flute are very similar in terms of their demands of the amount of air

because when you play the flute a lot of the air spills over the top and

it's wasted. It doesn't all go into the instrument. The bassoon

doesn't take nearly as much air as the contra; the contra takes substantially

more. And in terms of equating it with instruments

people know, I do a little bit of saxophone playing - more or less as a hobby.

The bassoon and the tenor saxophone need about same amount of air. The contrabassoon is much closer to the baritone

sax in terms of the amount of air you need to put through it to keep it

going.

BD: Should the baritone or the bass saxophone player,

or the contrabass clarinet player get their own solo shots too?

SN: I certainly can't speak for them, but I don't see

why not! Any instrument has its own individual

timbre and certainly deserves to be heard, and if people can write for it

and people can play it, I don't see why not. I just get a little distressed

after a while that every symphony concert you go to the soloist is always

a violinist, pianist, or maybe once in a while a cellist

or a flute... maybe the French horn. But you

hardly ever have a trombone soloist or a viola soloist much less a contrabassoon

or an alto clarinet or something like that. It just doesn't happen. For example, I love the Donizetti English Horn Concerto. It's a little

corny, it's a little wacky, but it's a wonderful piece and you never ever

see it programmed anywhere. I just think that's

such a shame that these other instruments don't have a chance to do that.

BD: Is there a camaraderie amongst those who play contrabassoons

in the big orchestras?

SN: Oh yes, I think there is. I

really do. There's the International Double Reed

Society which is made up of oboists and bassoonists.

They have an annual conference, and you always see a great fraternity

of bassoon players in general, but contrabassoon players in particular, because

there's not as many of us. The few times that

I've gone to take auditions for orchestras, you always see the same people,

and they're always sitting around talking and exchanging stories. They

seem to be a real fraternal group. Just because

of our small numbers, you get to know people, and it's not really such a

competitive atmosphere. It's more or less a fraternal one, which is

nice. There could be exceptions, and maybe

there are people that don't fall into that mold, but by and large, contrabassoon

players are fairly laid-back people and there's a lot of camaraderie among

us.

BD: I would assume that if you don't have that kind of

temperament, you would fall by the wayside.

SN: I think so. Most of the

contrabassoon players I've met have been really nice, friendly people, and

it doesn't seem like they have the cutthroat mentality that you find with

instruments where there's a lot more competition. That's engendered

by the instrument.

BD: Is that part of your own personality?

SN: I've often wondered if people that

had that personality choose the contrabassoon, or if the contrabassoon makes

you that way. I don't know. It's the old question

- which came first, the chicken or the egg? I

don't know. I consider myself to be sort of a

laid-back person, not real uptight or cutthroat or anything, and maybe the

instrument suits me for that reason.

SN: I've often wondered if people that

had that personality choose the contrabassoon, or if the contrabassoon makes

you that way. I don't know. It's the old question

- which came first, the chicken or the egg? I

don't know. I consider myself to be sort of a

laid-back person, not real uptight or cutthroat or anything, and maybe the

instrument suits me for that reason.

BD:

Did you start out on the bassoon and move to the larger instrument?

SN: I started out as a flute player believe it or not.

That was my first instrument. The flute is a wonderful instrument,

but I just was not a very good flute player. It wasn't my instrument. Everybody's got to find the instrument for them, so I played the flute for a couple of years until I discovered

the bassoon, and then of course I took over the bassoon right away.

It's a funny story: When I was in high school

I was in the Youth Orchestra of Greater Chicago. I

was a bassoon player who wound up at the bottom of the section who got stuck

playing the contra! I know that this happens

very often, but the thing is, once I got started I never wanted to stop,

because I really dug the instrument. I really liked it and I realized

that this was something I could do and be happy doing.

So that's how it happened. I was just at the bottom end of

the heap, and somebody had to play the contrabassoon on Death and Transfiguration, which was

the first piece I had to do. So that's how it got started, a long time

ago.

BD: And you've been happy with it ever since.

SN: I really have, yes. I didn't start doing the

solo thing for a long, long time, because, quite frankly, I didn't really

consider that that was a possibility. I just

tried to make sure that I got to play the contrabassoon in the orchestra

whenever one was required. Everybody else seemed

to want to play first bassoon all the time, so they never had to deal with

me, because I was more happy playing contrabassoon. That was what

I wanted to do. I got my first taste of the

contrabassoon solo thing when I was a student at Northwestern. The

Wind Ensemble was doing a piece by Henk Badings, a concerto for bassoon,

contrabassoon, and wind ensemble. At that time

it was a fairly new piece, and since I was the only one that wanted to have

anything to do with the contrabassoon, I was the one that got to do the contra

solo line. And it really got me thinking about

maybe doing some stuff with the contrabassoon that would be of a solo nature. But back then there was just nothing written for

the instrument, so it took a long, long time to actually make that happen.

BD: Do you make your own transcriptions?

SN: I do, up to a point. There's a lot of things

that you don't really have to do a whole lot with, as we mentioned, like

the saxophone music. All you really need to do is change the clef and

the key signature, though some isolated things don't fit into the register

too well. Some of the bassoon pieces I can play right from the music,

unless there's an extended amount of notes up in the upper register, which

really isn't practical for the contra. It doesn't go quite as high as

the bassoon and it doesn't really have the carrying power in the extreme upper

register. Sometimes certain sections that were

written for bassoon in the upper register have to be brought down to a lower

octave, or adjusted in some way. But, like I

said before, I'm not really a composer, so any adjustments I would do would

be of a very minor nature.

BD: But you're a professional on the instrument, so you

know what works! Even so, are there times when

the composer just looks at you and says, "Do it."?

SN: Yes, there have been times like that, so I said,

"Well, I'll do the best I can." That's all you can do. It's like, "The customer is always right." The

composer's always right, and if they don't want to change it... That's a very personal thing. A composer has

written some music and that's his piece of music. You

can make suggestions and you can make comments, but in the end it has to

be his or her piece.

BD: Are you basically pleased with what has been written

for you?

SN: I am. Some things haven't been done yet.

I would like to see some pieces written for the contra that have some elements

of jazz in them. I think the contrabassoon would make a really neat

jazz instrument. I've often thought that it could

be used in a jazz ensemble instead of a bari sax or a string bass.

It could have some little solos because it has that kind of a sound, and people

haven't actually seen that aspect of it yet. They see it as a more

serious instrument, which is okay, but it can also be a lot of fun and it

can also sort of swing. I would like to see composers

write some of that in a piece for me. Not that

I'm really adept at that kind of thing. I certainly would have to work

at it a little bit, because, being a bassoon player and a contrabassoon player

all these years, I don't improvise, and I haven't really done a lot of jazz

playing. But the instrument's got a good capacity for that.

BD: We're kinda dancing around it, so let me ask the big

question: what's the purpose of music?

SN: Oh, boy. The purpose of

music... Music is a universal language. It

can express things that you can't say. Basically, things that you feel,

that you can't ever really describe, you can do with your music. At least that's the way I feel about it. It tells a story. I've taught music for a lot

of years to children and a lot of kids have questions about it too.

I just say, "Listen to this and try to think about what's happening," or,

"How does it make you feel?" Not that all music

is programmatic, because it isn't, but music gives you a mood or it gives

you a feeling or makes you think about certain things. It conveys things

that words can't always do. That's just basically

the way I think about it.

BD: Should the music that you play be for everyone?

SN: No, no, I don't think so. It would be nice

if everybody could enjoy your music, but there are certain cultural differences

that sometimes make it different for different people. For example,

I love to listen to sitar music from India, but it took me a long time to

get into that because of the microtones they use and the different scales

and different patterns. For people to get into music that's different

from their background is sometimes a difficult thing.

I have no doubt that somebody from India listening to me play the

contrabassoon might not be all that pleased with what they hear because it's

just a whole different thing. It's important to listen to different

styles of music, but nobody is going to like all kinds of music. They

have to decide for themselves.

*

* * *

*

BD: Are you pleased with where you are at this point in

your career?

SN: [Thinks for a moment] I would like to be further along, or younger - one

of the two. [Laughter] I

wish I had started doing this a little bit earlier, but basically I'm glad

with what's happening. I just wish things could happen a little faster,

I suppose. I suppose everybody would like to

be a little further ahead. I'm further ahead

now than I thought I would be two or three years ago.

Things have happened for me the last couple of years that have been

really good, and I'm real pleased with that.

SN: [Thinks for a moment] I would like to be further along, or younger - one

of the two. [Laughter] I

wish I had started doing this a little bit earlier, but basically I'm glad

with what's happening. I just wish things could happen a little faster,

I suppose. I suppose everybody would like to

be a little further ahead. I'm further ahead

now than I thought I would be two or three years ago.

Things have happened for me the last couple of years that have been

really good, and I'm real pleased with that.

BD: Such as the recording?

SN: The recording was a big move in the right direction.

I wish I had done that earlier, but, thinking back...

BD: [Interjects] I don't think

the time was right, earlier.

SN: I think that's true. I don't think the time

was right earlier, and I don't think I, personally, was ready earlier. When I think about when I did that, if I had tried

to do it five or ten years earlier, I don't think I had the musical maturity

at that point and maybe not even the technical finesse to do what I did when

I did it. So maybe I wish I had developed, ten

or 15 years earlier so I could've started doing it sooner.

BD: We see this in opera singers all the time, the basses

tend to develop a little bit later, but then they last longer!

SN: That's true. I fully intend to live to be 100.

I have a long way to go and I want to play for a long, long time. I do everything I can to keep myself healthy and in

good shape so I can play the instrument. It's a big instrument to haul

around and it requires a lot of energy to play. You've gotta be healthy

and you've gotta have a clear mind. It's important to try to keep yourself

physically and mentally healthy so you can perform to your best ability. Then the longevity comes with that.

BD: Was the record your idea, or somebody else's suggestion?

SN: The first one was actually my idea, and it came in

sort of a roundabout way. I used to call myself

the "premiere contrabassoonist" before I got this "crusader on the contrabassoon"

idea. Because I had premiered so many pieces

that people had written - not that they had all been written for me, though

a couple were - but I had premiered pieces that had been written and never

played. Then I suddenly realized I had enough pieces that had been

written for me to fill up a compact disc! I had

about an hour's worth of music and I thought, "Gee, wouldn't it be nice for

these composers to have their piece recorded, so people could hear them at the same time? I got these pieces published so

people could buy them, and it wouldn't be bad for me, either, to be on a

disc." So it was a win-win situation for everybody.

BD: But it's interesting that you put yourself third.

SN: The performer is never the main thing. The

composer is because without them there'd be no music.

And the instrument has always been a primary focus of mine, to get

people to hear the instrument, not to get people to hear me. I'm just the person behind the instrument.

The instrument is the main thing.

BD: Are you part of the instrument, or does the instrument

become part of you?

SN: [Takes a deep breath] The

two of us are really inseparable. People always

caution you against relating too closely to your instrument. It's not a good thing to equate yourself with an instrument,

but I've really gotten to the point that if somebody makes a nasty comment

about the contrabassoon I take it personally. I

know that's not always a healthy thing, but I just relate so much to that

instrument it's become a part of my personality. It's impossible for

me to think of myself out of context with that.

BD: But you still put it aside, put it in the case at

night and close up the case.

SN: Oh, of course. Sure. I'll go out to a movie, or go out and do something

else, and enjoy myself, but it's always on my mind and it's always a part

of me. It's gotten to be that way. Most musicians, to a certain extent, do get to that

point. Maybe not to the extent that I have, because it's an unusual

instrument, and maybe because I find myself so much on the defensive because

a lot of people don't always say nice things about it. The contrabassoon

is the least-known instrument in the orchestra. Nobody knows what

it sounds like because they don't get a chance to hear it. Not too

many people could draw a picture of it. It's

just a big unknown quantity to people. Of the instruments that are

regular members of the orchestra the contrabassoon player sort of is the

wallflower.

BD: That's true. People know the piccolo, and they

know the bass clarinet...

SN: ...and the English horn. So

we're just trying, maybe in an obnoxious way, to just keep pushing it out

in the front so people see it all the time and hear it all the time so at

least they know it's there. They can dislike

it if they want to dislike it, but at least they have to know what it is and

give it a chance. Listen to it first and if you tell me you don't like

it after you've heard it, that's fine. But don't

tell me you don't like it before you've given it a shot.

BD: I have a feeling you will have really succeeded when

the audience goes home and says, "Gee... there was no contrabassoon tonight!"

SN: That would be nice! That

would be nice. It's only in about 35 percent

of the orchestral compositions at this point. I

read that somewhere, so about one piece out of every three, or one piece

on each program usually has a contrabassoon part. There

are whole programs, of course, that go by that don't have contrabassoon parts

at all. You get more in Romantic and modern music,

but more often than not it's a visitor to the orchestra just on part of

the concert.

BD: A regular visitor.

SN: A regular visitor. A regular

visitor.

BD: I hope that it's now being written as part of the

standard setup.

SN: I think it is. In orchestration

classes that are being taught, when they give people score paper to write

their orchestra piece, there's always a line for the contrabassoon, which

is good. It's real important, and sometimes

in chamber music they tend to think about it more often than they used to,

which is good, too.

BD: I know that there are even a couple

of pieces which call for two contrabassoons.

BD: I know that there are even a couple

of pieces which call for two contrabassoons.

SN: Yes! Yes, as a matter

of fact the Symphony's going to be doing the complete Firebird ballet two or three weeks from

now, and that's got two contrabassoon parts. The Rite of Spring is another one.

There's two pieces by Varèse, Arcana

and Amériques. Also Schoenberg's Gurre-Lieder. So

that's five pieces that I know right off the bat that have two separate contrabassoon

parts.

BD: What about a duet for two contrabassoons! [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Arthur Weisberg, and

William Eddins.]

SN: Donald Erb wrote Five Red-Hot Duets for two contrabassoons.

BD: Is that a good combination?

SN: I think so! I like it.

It's an interesting combination, the way he uses them.

He writes the first contrabassoon quite a bit in the

upper register, and then confines the second contrabassoon more or less to the lower register, so they almost sound like two different

instruments. It's very clever the way he did

that. It's a difficult piece, very difficult.

BD: I still think you should find a piccolo player and

go out as a duet.

SN: [Chuckles] Well, you never know what could happen.

I've tried to get some clarinet players interested in doing the Beethoven

duets for clarinet and bassoon. Maybe I can get some bass clarinet

player or something, but I haven't really been successful yet. So we'll

see. The contrabassoon has to play transcriptions. There are going

to be more pieces written for it, but you're never going to have enough material

that's original. When I first started out doing

this, I was real adamant. The first two or three years that I played

recitals, I wasn't going to play anything that wasn't written for the contrabassoon,

period. I was going to be a real purist, and after two years I ran

out of music. Gary Karr was the one who got me

into doing transcriptions. I had sent him a recording of my stuff and

had written him a note expressing frustration about that, and he said, "Hey,

get over that. If you're going to play a solo on this instrument, you

have to get out of the hang-up about using transcriptions

and play music that was written for other instruments.

There's no way around it." He really cured me of that, and really opened up whole new worlds to me.

Now I can think about playing music by Cherubini or

Rossini or Mozart on the contrabassoon, and that's

really neat! It works really well, but you just

have to realize that you're not going to do original

works all the time. And

actually it's good in another way because you might

play a piece of music that somebody recognizes. They've heard it before, like a couple of movements from a Bach cello suite. They've heard somebody play that, so they recognize the

music. That way it's not always a brand-new piece of music that they're

not accustomed to. It's something they've heard before, but in a new

context, so they can actually concentrate on listening

to the instrument, not just the piece of music, which

is good.

*

* * *

*

BD:

Coming back, for a moment, to the idea of becoming the instrument, I can

see, when you play it, that you have to hold onto it in a very special and

very intimate way.

SN: Yes! You sort of surround the instrument, you really do. When you sit to play it, you've always got one foot behind the floor

peg so it doesn't slip, and the other leg sort of in

front of the instrument to give it something to rest against. So you sort of cradle the

instrument with your body. Then you're holding

it with one arm and supporting it with the other, so you are surrounding the instrument in a way.

BD: You have to be half athlete and half contortionist!

SN: If you were extremely fat it would be a problem because you wouldn't

be able to get close enough to play the instrument. And if you weren't

real agile it could be a problem, too. Also there is the issue of just

carrying the instrument around. It's a big, heavy instrument which weighs

about 15 pounds, and that's not counting the case, which usually weighs another 15 pounds or so.

So you have to be in some sort of decent physical

shape just to be able to haul the thing around up and

down the stairs and things like that.

SN: If you were extremely fat it would be a problem because you wouldn't

be able to get close enough to play the instrument. And if you weren't

real agile it could be a problem, too. Also there is the issue of just

carrying the instrument around. It's a big, heavy instrument which weighs

about 15 pounds, and that's not counting the case, which usually weighs another 15 pounds or so.

So you have to be in some sort of decent physical

shape just to be able to haul the thing around up and

down the stairs and things like that.

BD: A bowling ball is 16 pounds...

SN: Is it really?

BD: Yes. So you're carrying around the weight of

two bowling balls.

SN: Well it's good exercise. It's sort of a circular

thing - it's good to do it because it keeps you in shape, but then

you're in shape because you're doing it. Also it's good for your lungs, too. It does take a certain quantity of air, so you've gotta have good breath control

to be able to play it. It's almost therapeutic

- the more you play it the more you develop your breathing capabilities! I find when I pick up the bassoon I can play it forever before I have to take a breath, which is wonderful! It's nothing that I've done. I'm not trying to pat myself on the back, but it's just because of playing the contra so much you get used to dealing with large volumes of air.

You take in a full breath almost every time, so as a result, when you're playing a smaller

instrument that doesn't require as much air, you can just keep going and going and going and going!

BD: Like the Energizer Bunny!

SN: Exactly.

BD: Have you ever tried putting a contra reed on the single

bassoon?

SN: Yes. Everything comes out a half-step lower. So you could play a low A on the bassoon if you put

a contrabassoon reed, but the timbre is not real good and it's sort of a fuzzy sound.

BD: In the Nielsen Quintet,

you have to stick something in the bell (of the little bassoon) for the

low A at the end. Is there anything like that

for the contrabassoon that you can do to make it a little lower?

SN: I've never done that. First of all, you're sort of limited in that the bell already points down, so if you're going

to stick something in there, it's probably going to

fall out unless there's some way of actually affixing it.

There are some contrabassoons that are built

to go down to a low A. Heckel

builds one that has like a detachable bell, so you

can choose either a short, straight bell, which goes down to low C, or you can change

it and put in this whole other connection which goes all the way down to

a low A. So that is one

possibility.

BD: Like more tubing on the bass trombone.

SN: Exactly. But the problem with that is that it throws off the scale and it makes a lot of changes in the timbre. Plus some of the notes in the low

register are a little bit out of tune because of the

extra linkage. There is one contrabassoon player in Austria who does a little bit of solo work himself, who has built for himself a contrabassoon which goes down to A-flat, which must be just

a horrible thing to have to carry around. That extra semitone, just from B-flat to an A, adds over an extra foot. So down to

the A-flat we're talkin' another 18 inches, maybe.

I'm not sure that it's worth it, but I'm sure he had

a reason for doing it.

BD: There are Bösendorfer pianos that have extra

keys down at the bottom, so it's probably the same kind of thing.

SN: I suppose that's true. I've

competed with those instruments in recital. I did a recital once on the contrabassoon

where we had one of those pianos to deal with, and of course it reinforces all the

low register which, for me, was the worst possible thing that could've happened. You can't

run interference with the piano.

BD: [Chuckles] In the end,

though, I hope you find it's all worth it.

SN: It is.

It is. This has become my life,

it really has. I used to resent

it when people thought of me just as a contrabassoon

player, but now I think of it

that way. I don't like them thinking of me as

the "big bassoonist." That's the one thing that

I've had to deal with since I've gotten this "big bassoon"

thing.

BD: I like it when you leave messages

on my phone: "Hi, it's Sue Nigro, the contrabassoon

player." It reinforces your cause. You're reminding them that the contrabassoon is out there. Don't forget me.

SN: If I can leave some sort of

a legacy, it would be to make

people more aware of the instrument, and to be more willing to listen to

it. And to like it, of course. I can't

make them like it, but I can hope that they'll like

it, and I can do my part to make it sound as good as I possibly can, so they'll have a favorable

impression of it.

BD: Thank you for the conversation.

I appreciate it very much.

SN: My pleasure.

This interview was recorded in Chicago on March 24, 1997. Portions

were used (along with recordings) on WNIB later that year and again the following

year, and on WNUR in 2004. This transcription was edited and posted

on this website in 2008.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.