Tubist Gene Pokorny

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Going to the Lyric Opera and the Chicago Symphony regularly

all my life, I admit to being spoiled by the greatness of the world-class

musicians who present a vast array of musical literature. It has

also been my extreme pleasure to be personally close to a number of those

performers. One such is Gene Pokorny, the Principal Tuba of the

CSO.

After the renovations and re-building of Orchestra Hall into Symphony

Center, it was easy to wait in the rotunda after the Thursday night

concerts and greet some of the players. Being particularly affable,

Pokorny would often stop and chat not just about music, but various

this and that. Like the cherry on top of the sundae, it made the

evening extra special, and sent me home with a warm glow.

In June of 2002, I persuaded my friend to come early and meet

for a conversation. We set up in one of the practice rooms downstairs,

and had a wide-ranging discussion. Besides the insights and professional

observations, there was much laughter.

My longtime radio home of WNIB, Classical 97, had been sold and

changed format the previous year. I had, of course, played some

of Pokorny’s recordings on numerous occasions,

but we had never done a formal interview. So, when I was asked

to continue my series of programs on WNUR, the station of Northwestern

University, my first thought was to get some of my local friends to share

their thoughts, and this interview was set up. Portions were

aired a few times, and now, late in 2021, I am pleased to present the

transcript of the entire encounter on this webpage.

As always, names which are links on this page refer to my interviews

elsewhere on my website.

Here is what transpired nearly 20 years ago . . . . .

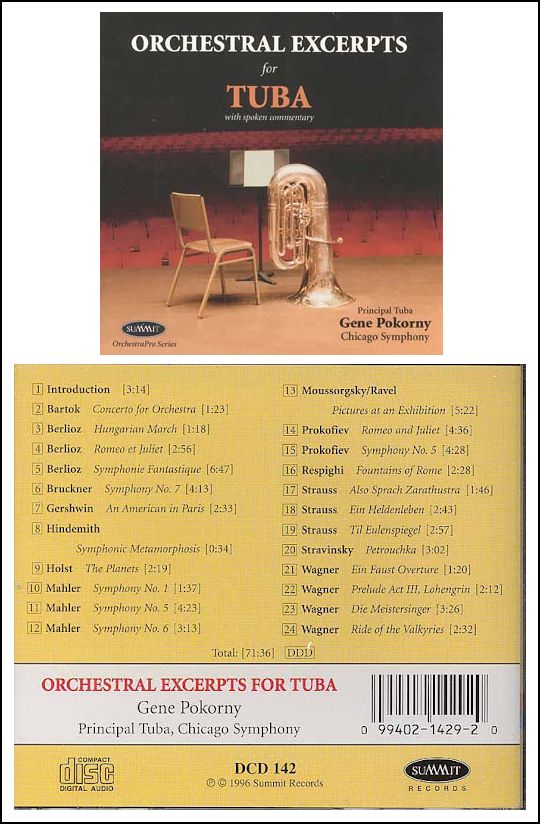

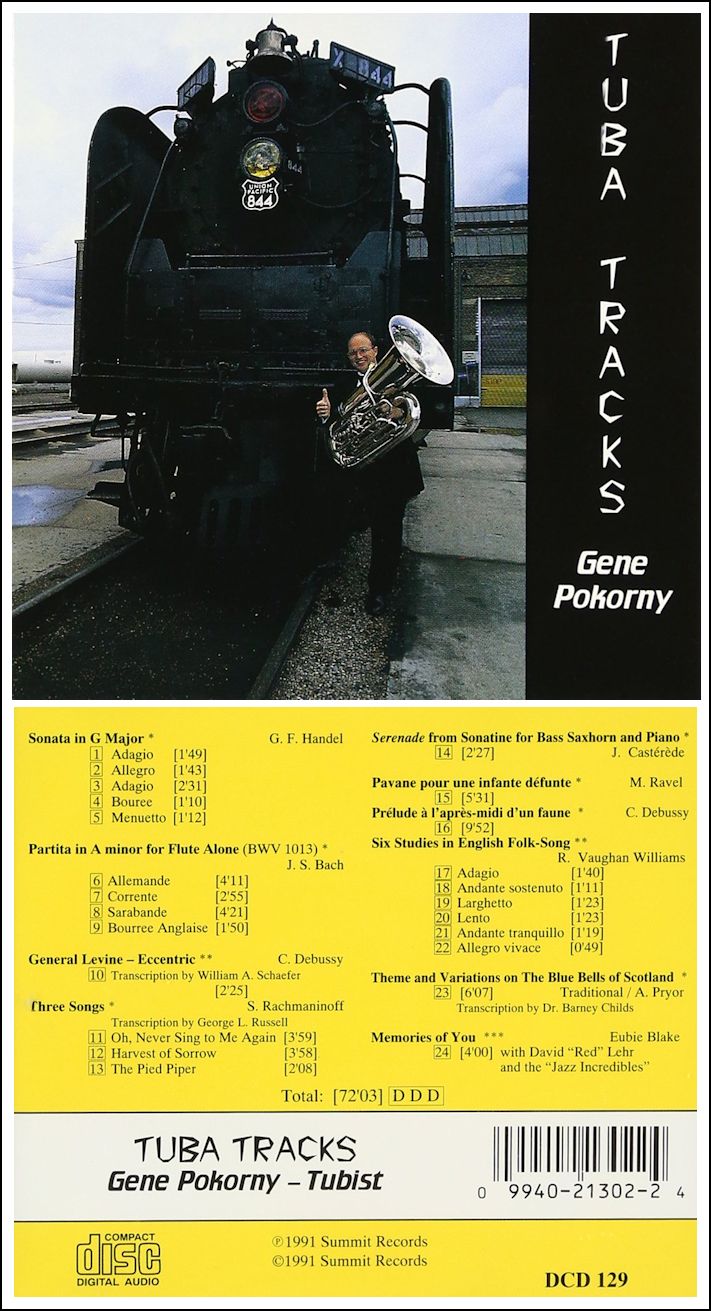

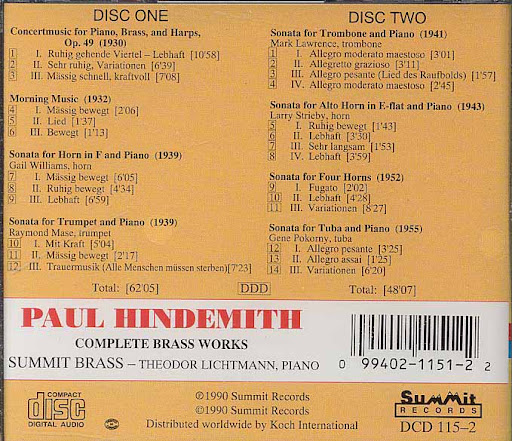

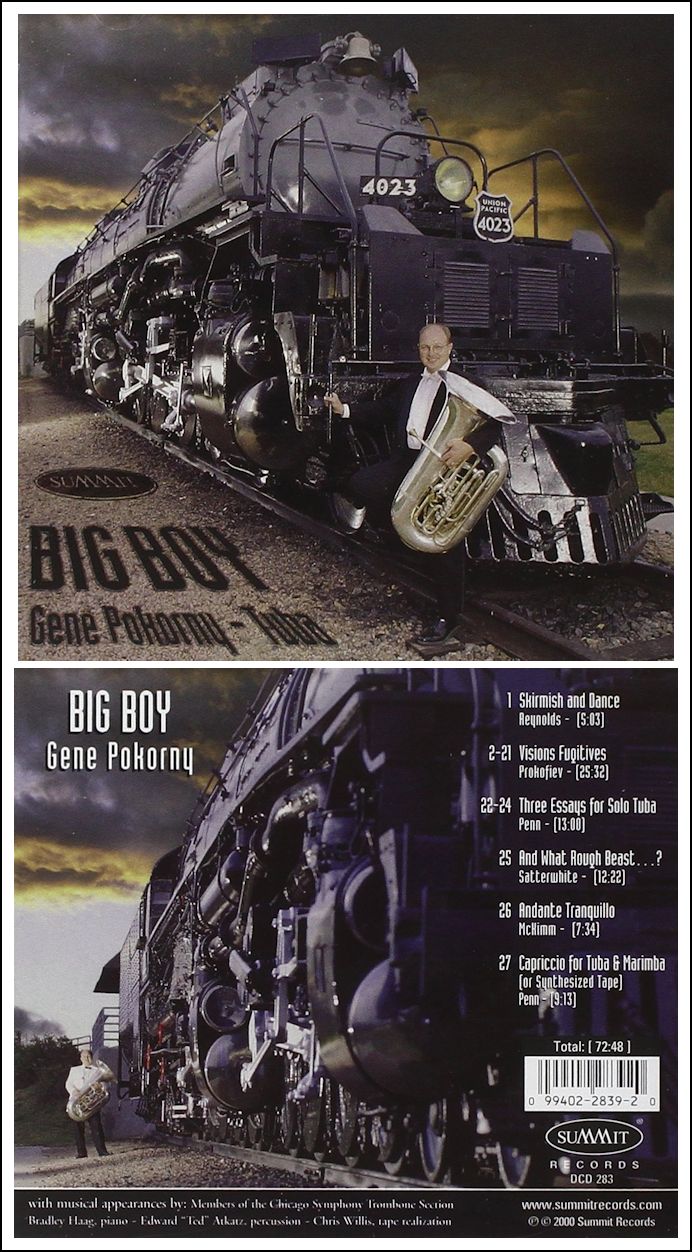

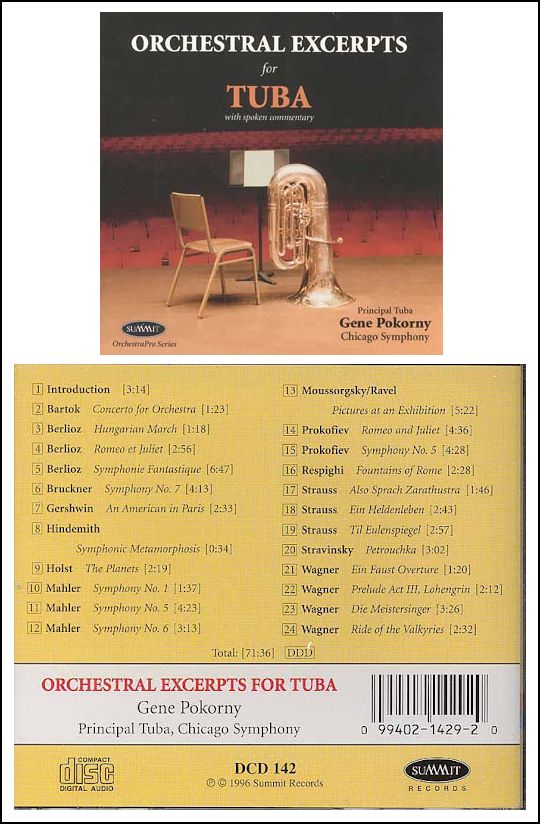

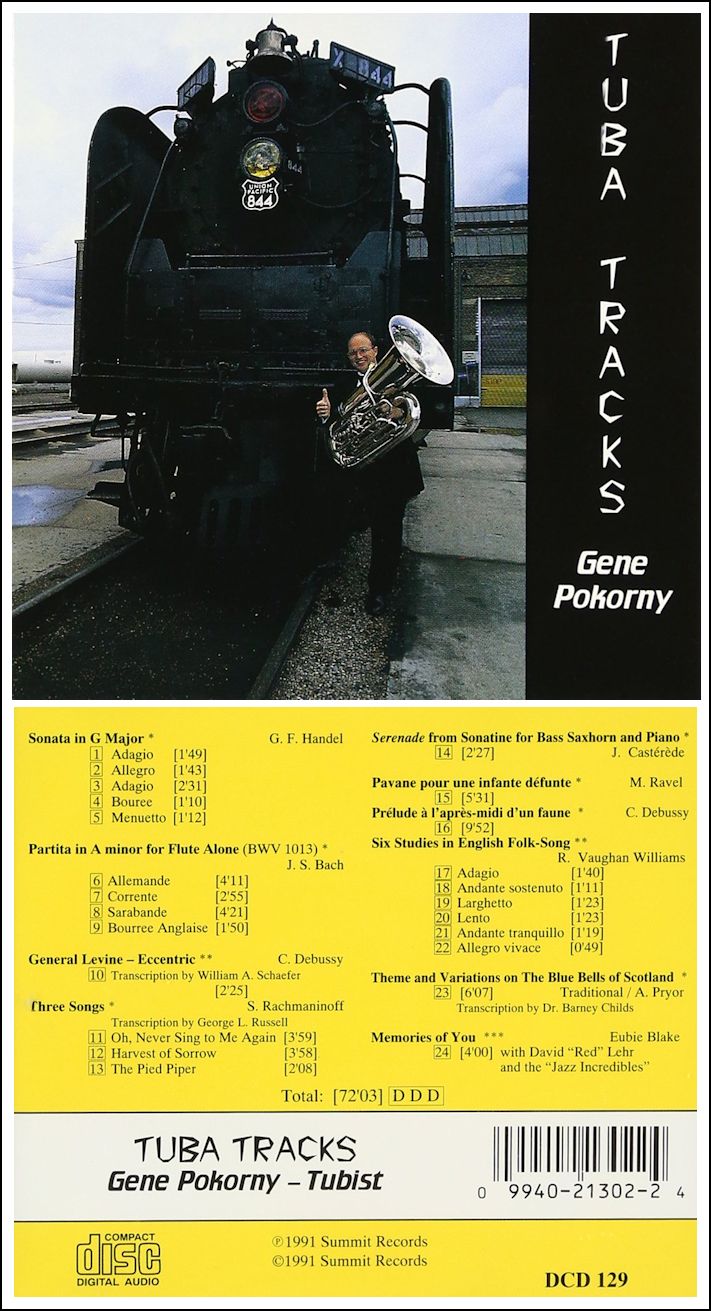

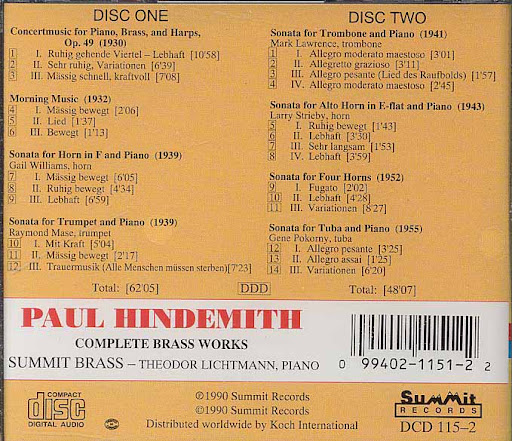

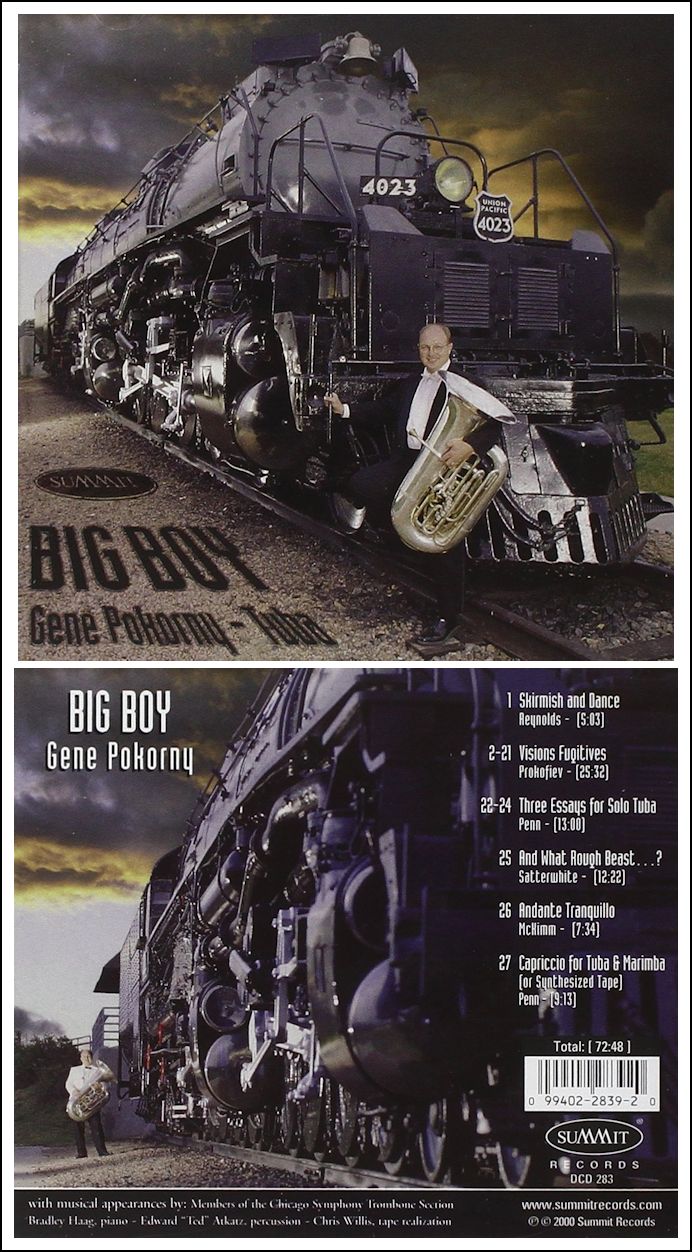

Bruce Duffie: We’re talking about a series

of recordings on the Summit label of orchestral excerpts. Each

instrument has a recording of a great performer on their instrument,

playing excerpts and talking about them.

Gene Pokorny: Right. Every performer

talks about the various excerpts. Sometimes those performers

demonstrate the excerpts being played in different ways and different

styles. The whole idea got started with a tuba student of mine,

Edward B. Luker, who happened to be a retired Union Pacific Railroad engineer.

He was very interested in learning the tuba. He was 70 years old

at the time (~1982), and I gave him a couple of lessons while I was playing

with the Utah Symphony. He said, “You really should think about doing

a recording like this.” So, on a Summit Brass tour, we were sitting

around in the airport waiting lounge, and I mentioned Luker’s

idea to Ralph Sauer, the Principal Trombone in the LA Philharmonic, and

Gail Williams, who was Associate Principal Horn here in the Chicago Symphony.

We talked with Dave Krehbiel from the San Francisco Symphony, and when

we arrived at the hotel of our next destination, we got together with Dave

Hickman, who runs Summit Brass and was president of Summit Records. He

said, “This is a real good idea for a project.” Soon after that hotel

meeting, the ball started rolling, and the recording project was set up not

only involving Summit Brass musicians, but woodwind and string players as

well. These educational reference recordings have been made by a wide

variety of artists, and have been heard by many young players from all over

the world. I think they have helped raise the standards of orchestral

audition playing.

BD: Can I assume that something these records

would coincide with the excerpt book that each performer has practiced

before going to auditions?

BD: Can I assume that something these records

would coincide with the excerpt book that each performer has practiced

before going to auditions?

Pokorny: Sure. When one auditions

for an orchestra, the parts don’t change significantly, if at all.

The problem is actually getting a concept of how these can be

played. It takes a lot of effort to get one’s

playing into ‘camera-ready’

shape for the rigors of an orchestral audition.

BD: Are these excerpts particularly

difficult, or just exposed?

Pokorny: A lot of them are exposed.

They become solos, as in a short section in the middle of Gershwin’s

American in Paris. They’re just for the tuba players.

That solo is not particularly difficult technically, and is not at all

difficult with the other players who are playing at the time. However,

it is unique in its rubato and espressivo qualities, given that

it should be played in a jazz style. Contrarily, many excerpts are

played with the trombone section where the tuba is the low voice in the ensemble,

and he or she has to make it sound like one instrument down there.

For example, Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries

is played with two tenor trombones, a bass trombone (or perhaps a contrabass

trombone), and tuba. The excerpts asked at an audition all have a particular

skill that needs to be demonstrated in order to identify the candidate who

has the most abilities to to bring to the tuba chair.

BD: Just to see your technique?

Pokorny: Technique, tone, and musicianship.

One may have a great ability to play quickly and effortlessly, but

if the sound is unpleasant or doesn’t blend in and support

the trombone section, then that will be a warning sign to the audition committee

to steer clear of that player. I have an anecdotal story about The

Ride of Valkyries. [Vocalizes the famous melody]. My

own personal experience with that piece is that I had played it for every

audition for every orchestra I’ve ever auditioned for, including the

Israel Philharmonic, which didn’t start playing the piece until just

a few years ago. You just don’t play Wagner in Israel. [Both

laugh] Because in my career I only stayed in one orchestra for

a few years before I would move off to another

— Utah, then St. Louis, then LA

— I never actually got a chance to play the

piece in the orchestra until I came to Chicago, which was fifteen years

after I had started playing professionally. Coincidentally, it

was never scheduled with an orchestra when I happened to be employed by

that orchestra, but, as I said, I had to play it for every audition for

every orchestra. [To see a comprehensive article Pokorny has

written about auditioning, click HERE.]

BD: You could say you were really ready

for it!

Pokorny: I was extremely ready for it.

I was so boggled about it that I brought eight dozen donuts

to the first rehearsal. It was such a big moment to actually

play this piece after having been behind the screen with it so many

times. Finally I actually got a chance to play it through.

Then we recorded it with Barenboim two weeks

later, and I brought a dozen donut holes. [More laughter]

BD: We’re talking about auditions. I

assume that many years ago, orchestras were just glad to get some

guy who could get around the notes, and hope he played most of them

correctly. Has the playing of the tuba progressed to a point

now where they want real expert professional musicians who can tackle

all of these tricky parts?

Pokorny: With every instrument the competition

level is a lot higher, and there’s a lot more people who can perform

at a higher level as the years progress. We’ve always had those people

in the past who have stuck out — like

Arnold Jacobs. When he got the job here, he stood out among

everybody who was playing. Even in those times, tuba players

generally had to double on string bass to play in an orchestra. That

certainly was the case in Europe.

BD: They would play the string bass regularly,

but then when they needed the tuba, they would play that?

Pokorny: Yes. That was how the

job was divided up not so long ago. I spoke with Rudolf Levy, one of

my predecessors in the Israel Philharmonic, and that was how the position

was defined — some

tuba and some string bass. The tuba was almost kind of a sideline.

The current tuba players in music schools can play circles around

those who played professionally not so many years ago. At least the

technique is very much advanced. Are these musicians as fine as what

was found professionally in the past? Maybe. I know

that I would have to be a lot better than I would have been when I auditioned

for the positions I won in the past.

BD: Is this partly a tribute to Jake,

and to you, and to the few others at the top of the profession?

Pokorny: I’d say that all of us wouldn’t

come to our level of playing if we weren’t standing on the shoulders

of people who have gone before. I certainly got a lot of help

from my teachers, which included Roger Bobo of the LA Philharmonic,

and Tommy Johnson, a Hollywood studio tuba player, who basically built

me from the ground up. He was the one who really told me and showed

me what was right, and how to get my playing up to the proper level. Arnold

Jacobs must have been some type of freakish genius when he came on the scene.

He represented and popularized the type of playing that given to him

by his teacher in Philadelphia, Philip Donatelli. Jacobs stood on the

shoulders of Donatelli, whose recordings with the Philadelphia Orchestra

and Stokowski, demonstrated that representative sound that Jacobs took to

so many other tuba players.

BD: Does Bill Bell come into this at

all?

Pokorny: When I first entered college

in September of 1971, I felt guilty about having an hour off in the

middle of the school day. That never happened in high school, where

you started at 8 AM, go to classes all morning, and then, after lunch,

go to more classes, have band rehearsal, and then go home. So here

I was at 2:00 in the afternoon, and I had a few hours off. So I went

to the library at University of Redlands, and

figured I better do something. Anything! [Laughs] So,

I picked up The Instrumentalist magazine, and there I read an

obituary about this fellow named William Bell. I’d heard his

name and seen his picture on some method books, but never appreciated

what he was all about. Then, after going to an international tuba

symposium in 1973 at Indiana University, where Harvey Phillips taught,

I got the whole lowdown on this guy. Growing up in LA was very

good, in that I had the best players around to emulate, namely Roger Bobo

and Tommy Johnson. I didn’t know anything existed on the East Coast,

which in my frame of reference meant anything east of San Bernardino.

In California, the view of the world starts with Santa Monica and ends

with San Bernardino. It’s always 75 degrees, partly cloudy in the

morning, and hazy sunshine in the afternoon. That was it. That

was my life. But back to Bill Bell. He made the tuba into a

musical instrument. The recordings he made where he played

and sang were tongue-in-cheek fun solos about the stereotypical tuba player,

hippos, and the like. He poked fun at us tuba players, but it made

us more human in a way. Of course, eventually we would all like to

be taken somewhat more seriously, but we cannot ignore what is so obvious

about us. Bill Bell did a lot of good, and encouraged the first generation

of ‘serious’

tubists (such as Phillips) to set us on a road of respect and progress.

* * *

* *

BD: Let’s go back even farther. Did

you start immediately on tuba, or did you begin with a smaller instrument?

Pokorny: I started on piano, so that’s

a big instrument. [Both laugh] My dad played trumpet

when he was growing up in Omaha, Nebraska, and I got interested in

trumpet and played his old trumpet when I was in elementary school.

BD: You got used to the brass embouchure

then?

Pokorny: Yes, but in the wrong way. I was

pressing the mouthpiece into my lips with too much force, and also using way

too much air pressure. I just got off on the wrong foot. My

dad was so upset at the way I was approaching the trumpet that he said,

“Why don’t you take up something else, like saxophone,” which I did.

I went to saxophone and, eventually, clarinet. It was probably

my second year in junior high when they needed somebody to play tuba,

so I picked up the tuba which was a better fit than a trumpet as a brass

instrument for me.

Pokorny: Yes, but in the wrong way. I was

pressing the mouthpiece into my lips with too much force, and also using way

too much air pressure. I just got off on the wrong foot. My

dad was so upset at the way I was approaching the trumpet that he said,

“Why don’t you take up something else, like saxophone,” which I did.

I went to saxophone and, eventually, clarinet. It was probably

my second year in junior high when they needed somebody to play tuba,

so I picked up the tuba which was a better fit than a trumpet as a brass

instrument for me.

BD: You understood how to use the right

amount of pressure and the right embouchure?

Pokorny: I dont know that I understood

it, but it seemed to be a lot more natural for me. You use a much

greater volume of air than on trumpet, so you’re going through a whole lot

more air with less pressure.

BD: That’s when

you decided to stay with the tuba?

Pokorny: Yes, particularly after I met

Jeff Reynolds. I played in some brass quintets when I was in

high school, and was invited to play at the Moravian Church in Downey,

California, where I grew up. The choir director happened to be a

trombone player, and one particular Sunday he played a solo. I told

him, “You’re a good trombone player.” The next week, I read that

Reynolds had just been accepted as the bass trombonist in Los Angeles

Philharmonic. [Both laugh] Open mouth, insert foot...

BD: No, that means you could call it

correctly!

Pokorny: Anyway, I started

to get very serious about the tuba after meeting him, and he has remained

a hero of mine. It was easy for me to figure out that he was a superlative

trombone player. You would have to be deaf not to know that. His

abilities as a player, composer, arranger, organizer, dreamer, comedian

and inspirational character pushed him well into the hero category for me

through all my days as a musician.

BD: In the orchestra, the tuba player always sits

next to the bass trombone player. Aside from valves versus a slide,

is there a lot of difference between the bass trombone and the tuba?

Pokorny: There’s definitely different

timbres that can come out. Even when they play in tune, a lot

of times the bass trombone and the tuba aren’t matched, and they can

sound quite a bit different.

BD: The instruments don’t match?

Pokorny: Yes, the instruments don’t

match unless the bass trombone tries to sound somewhat like the conical

tuba shape, and the tuba player gets a little bit of the cylindrical

sound going at the front, and tries to sound like a bass trombone.

Then you have a pretty good marriage of sorts. But, a lot

of times you’ll hear some recordings of unmatched sections. Then

you have the bass trombone sounding like someone’s ripping canvas, and

below that there’s this loud refrigerator motor. [More laughter]

BD: Like they have matching Stradivariuses

for the four principal string players, should the big orchestras have

matched sets of brass instruments for the trumpets and the trombones

and the tuba, and even the French horns?

Pokorny: It does happen in some cases.

The Vienna Philharmonic has their own set of very special very unique

horns. Our trombone section here in Chicago play their regular

instruments, mostly Bach trombones. But they also have a set of

trombones made by Heribert Glassl, a German trombone maker, which are

slightly more conical, and produce a less direct sound than the American

Bach trombones.

BD: Is it the section leader that decides

each week which set to use?

Pokorny: Generally, yes. Jay Friedman, our

principal trombonist, is extremely open to hearing what other people

in the section have to say. There will also be communication with

the trumpet section, because if they’re going to use rotary trumpets,

then the trombones will try to concur and use the German trombones. When

we’re doing a Dvořák Symphony, and the guys decide to use the

German trombones, I will use a smaller Czerveny tuba, which is a less

aggressive-sounding, smaller Czech tuba.

BD: Tell me about the different instruments

that you have, and bring to use with the Chicago Symphony.

Pokorny: The instruments that I use exclusively

with the orchestra are two tubas made by the York Band Instrument Company,

which belonged to Arnold Jacobs. The Chicago Symphony thought

it’d be a good idea to purchase these instruments from Arnold Jacobs

‘to

keep them in the family’.

These are the instruments that recorded everything he did within

his tenure in the orchestra from 1944 through 1988. I usually play

the York tubas because they are so good, and they are the mainstay. In

addition, I have an F tuba which is used for higher tessitura pieces.

I also have a smaller euphonium-sized instrument. I have also

dabbled with the BB-Flat tubas, which are very large German instruments.

BD: The Yorks will stay with the orchestra after

you’re gone?

Pokorny: Yes, the Yorks will stay here.

I am responsible for them while I am this orchestra’s

tuba player, and by choice I play these tubas exclusively. Most of

the orchestral music played by the tuba should be played on a contrabass

tuba, and I will use one or the other York tubas. If it’s a piece

that has a high tessitura, or if the sound required is more closely

associated with the woodwind section —

such as a quiet part from A Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture

— then I might use an instrument like

an F tuba, which is a bass tuba as opposed to a contrabass tuba. Then

the sound matches a little bit better. The middle part of the

Tannhäuser overture really has a tendency to almost be

like an ophicleide part. The trombones have cut out, and I’m playing

with the low woodwinds, and that matches much more amenably with an F

tuba. [Photos and a bit of information about the ophicleide

family can be seen part way

down on this page.]

BD: Are we getting to the point where

it’s expected that in any major orchestra the tuba player will know

all of these things that you’re talking about, and use these different

instruments to match the various sounds?

Pokorny: There’s a certain understanding

that students will get from their teachers, but it is when the students

are ‘in the trenches’

that the real learning takes place. Theory is different from practice.

They may have to go with what is practical rather than what is ideal.

They will have to realize that the conductor is always right... even

when he is wrong! That means a conductor might have an idea of which

instrument or mute the tuba player should use. These are all things

a player must learn in order to survive in this rather unique institution

known as the Symphony Orchestra. However, the quest for finding the

best sound should never cease. It is a continuous search, and it is

one that needs the synergistic cooperation of your trombone colleagues.

Being an independent component is OK, but it is not the most mature

solution. Being an independent participant is he highest attainment.

Teamwork always wins over the victory of an individual in an orchestra.

Much of that will not be learned until the player is ‘on

the job’.

BD: Is that where the musicianship truly

begins?

Pokorny: Yes. The musicianship,

and the listening, and the whole spirit of being a team player is

where the rubber meets the road. There’s a big question out

there as to whether we’ve lost some of that ability to make the team

the highest priority. Unfortunately, there are examples of players

with self-centered delusions of grandeur in our world, but these are more

often delusions of adequacy.

BD: Is this loss just in the low brass,

or is it in the whole orchestra?

Pokorny: In the brass section in general.

Sometimes people see something on the page, and they want to

be heard. Even if it’s the most minuscule thing that’s going on,

and is only a supportive part, they like to know that every note they

play is heard out there. Sometimes just being felt

— not even being heard

— is more of a realization of what it is to be a

good orchestra player. So, yes, it takes a while to get used to

the maturity aspect of the gig, and not just try to sound like we are ripping

wall paper down incessantly. [Both laugh] Sometimes it’s fun,

but it doesn’t mean that there’s a lot of great music going on.

* * *

* *

BD: You mentioned being an orchestra player.

Is there a big difference playing tuba in an orchestra as opposed

to a band, or a chamber ensemble, and also in solo recital?

Pokorny: [Pauses a moment] It’s

been such a long time since I played in a band...

BD: [Apologetically] Sorry, ‘Wind

Ensemble’.

Pokorny: Yes, Symphonic Wind Ensemble,

or Wind Orchestra, as we used to call that back at USC [University of

Southern California]. I’d say there’s probably a lot more teamwork

required when you’re sitting with a section of tuba players. You

have a lot more potential for growth and making great sound if you’ve

got another two or three players beside you, where one can spot you while

you’re taking a breath, and then you can spot them while they’re taking

a breath. Think of the amount of air that’s required of the

trumpet player, for instance. The lead voice in the brass choir

of the orchestra or the band is using small amounts of air, generally

under higher pressure. That means they can probably hold a phrase

a whole lot longer than you can. If you’re playing loudly in the

low register, tuba players have been clocked at going about 140 liters

of air a minute! And that’s assuming there’s any air that bypasses

and gets to the brain! So, how do you keep all these notes going as

long as the trumpet player, who is using only one-third of the breath capacity

of the tuba player? Generally, when there’s only one tuba in

a section — which is what you

find in an orchestral situation — you

have got to mask the breath, or wait for some big percussion or timpani

entrance. Those are the folks who can thankfully cover up the tuba’s

breath before playing again...

BD: ...and actually be at the level

where you were.

Pokorny: Right. Or, if you do take

a breath, you want to make sure that people don’t hear you come in

again. It’s a bit of an art form. What’s remarkable are

some of the old CSO recordings, because Arnold Jacobs was seemingly a

master at this. His air capacity was really limited. Even during

his healthy years, he had barely more than three liters of air, or maybe

slightly more than that, but certainly not more than four, and towards

the end of his career, he didn’t have more than a liter and a half.

In other words, the ‘bow’

he was working with was rather short, but somehow you never actually

manage to hear him run out. Some of those recordings are unbelievable.

The sound just never seems to stop. You know he had a take a

breath somewhere, but somehow he managed to mask all those breaths in

such a way that you can’t really hear them. In a band, when you’ve

got a couple of players, this is easier. Each December, when the

Midwest Band and Orchestra Clinic happens, whenever I have a chance,

I try to go down there and hear some of the professional military bands

that come in from Washington DC — the

US Marine Band, or the US Army Band, or the US Air Force Band, etc. These

guys are professional tuba players who play in sections in a band,

and it’s remarkable because here is the ultimate tuba sound played in

octaves with absolutely endless supplies of air, because everybody is

spotting everybody else, and it’s just one continuous push of air. There

seems to be no air problems.

BD: If you’re in an orchestral situation

where you’re the only one, and if the last chord is just the brass

choir, can you go to the conductor and ask him to watch for when

you run out of breath, not the trumpet player?

Pokorny: It would be nice to have that

amount of freedom, but generally you don’t like to let the conductor

know that there’s nothing you can’t do. When

you’re in a chamber ensemble setting, it’s

easy. You can say, “When I start to turn

blue, or when my feet start to lift off the ground, that means we’re

getting into the red zone folks, so let’s get to the end of the tunnel

fast because we’re running out of air.” But

there are times, especially when we’re on the last note of a chord,

when the orchestra is playing as loud as it can, and the percussion is

going crazy. Then, after it’s over, I’ll

ask Charlie (Vernon),

the bass trombone player, how many breaths he took. [Both laugh]

BD: When it’s loud,

I would think it would be easy. But soft would be much harder

because it’s more noticeable.

Pokorny: Yes. You definitely don’t

want to take a breath if you are one of the few that are playing when

it is soft. Fortunately you can often find places where there’s

something else going on that will mask your breath. There are also

places where you can actually circular-breathe. Some tuba players

can do that just magnificently. Sam Pilafian, who

played with the Empire Brass for many, many years, and is now a great

jazz player and teaches at Arizona State, is just a master of circular

breathing.

BD: You make yourself into a bagpipe!

Pokorny: Right! You have a three-liter

air capacity just in your cheeks. We’re not talking about your

lungs, yet. I once heard a Bach Sarabande from one of

the Cello Suites that Don Harry, the tuba player in the Buffalo

Philharmonic played in the 1973 symposium, and it was just unbelievable.

It’s more of being tuba jock instead of a musician. To some,

the technical requirements of playing and inhaling at the same time were

more interesting than the musicianship he displayed. How did he do

it???

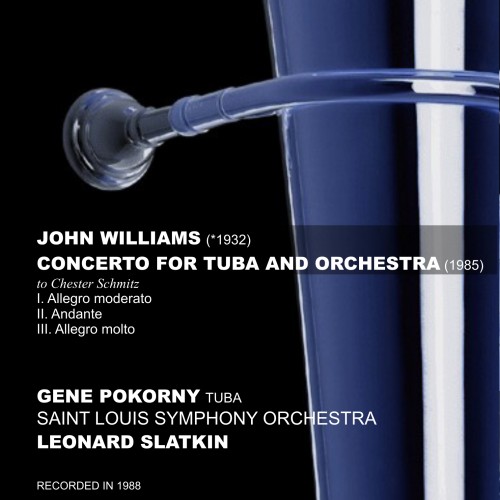

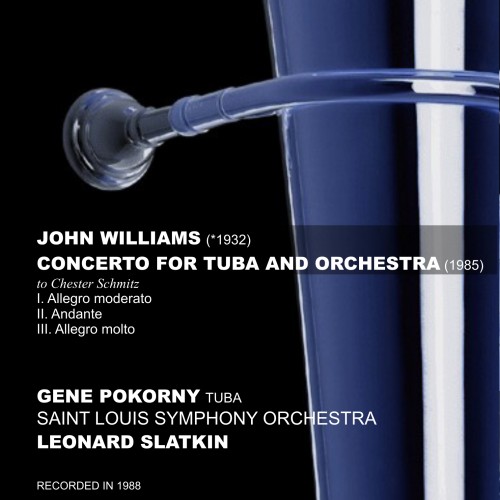

BD: As we progress, is this going to become

standard, so that 20 or 30 years from now every player is going to

have to be able to do this, and do it well? [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown at left, see my interviews with Leonard Slatkin.]

Pokorny: If you have the basic technique

together — like being able

to play a singing phrase with a certain amount of nuance and dynamics

— circular breathing is just icing on the

cake. But, as I point out on that orchestra excerpt recording,

auditions are affected by the unintentional and the unexpected. When

Chester Schmitz, the former tuba player in the Boston Symphony, auditioned

for Erich Leinsdorf,

he played a section from the Mahler Symphony #1. At the beginning

of the third movement is the lovely ‘Frère

Jacques’ solo in a minor key. It starts

off with a bass, then goes to the bassoon and then the tuba. What

people most likely don’t catch is that after the tuba finally gets

to the end of that little solo, the last note continues on for another

18 bars or something like that. You’re supposed to sit there on

that D natural, and just keep holding it... long after your breath capacity

has been reached!

BD: [Surprised] Did Mahler not

understand that you’re going to run out of breath, or need to take

breath???

Pokorny: That’s interesting, because

generally he was a micro-manager. He micro-managed everything

— little accents here, and don’t do this,

and watch out if you can’t play this note soft enough, give it to the

contrabassoon. He was a real nudnik about stuff like that. But

for some reason he let that one go. I guess he figured that the tuba

player would find the best place to take a breath. But in this particular

audition that Chester Schmitz took, he could circular-breathe, and he held

this note out seemingly forever. This is all hearsay. I have

never seen it actually documented, but Leinsdorf was completely blown

away. He was so fascinated by this little trick that

it’s almost as if it didn’t matter what Schmitz did for the rest of the

audition. I guess you just learn to do it in your spare

time when you’re in the army band, which is what he did before.

Tuba players at universities have Tone-Offs, where everybody

plays a D as long as they can. People bring in beer and sandwiches,

and you start off with 16 guys. Eventually one guy is left who’s just

sitting there playing that D.

BD: [Recalling the movie They Shoot

Horses, Don’t They?] They

shoot tuba players, don’t they? [Both laugh] The longest-held

note should be in the Guinness Book of World Records.

Pokorny: There is something in the

Guinness Book... Some guy backpacked his tuba up Mt.

McKinley, and played the lowest notes on the highest mountain.

BD: Did you ever take your tuba up

to the Sears Tower [at that time, the tallest building in the world]

and play the lowest notes off the highest building?

Pokorny: That would be an

interesting project.

* * *

* *

BD: Have you done everything you want

to do on the tuba? Are you looking for more new ideas?

Pokorny: It’s always fascinating to listen

to music written for flute or clarinet, and try to play it on the tuba.

I always try to make the transcription sound better than the original

version.

BD: What about the Flight of the

Bumble Bee?

Pokorny: That’s already been done! There

is this one tuba soloist out there whose name is Pat Sheridan. He

is a total maniac. I saw him do Flight of the Bumble Bee

at the Midwest Band Clinic a few years ago. He was dressed in a

black leotard with yellow stripes around his middle, and he wore two little

pointy antennae, and he did Flight of Bumble Bee. He was

in front of the orchestra. He’s rather hefty, bigger than I am,

so he was pushing I’m sure 320-350 pounds. He was simultaneously

dancing and playing Flight of the Bumble Bee faster than you’ve

heard any flute player. It was just unbelievable.

Pokorny: That’s already been done! There

is this one tuba soloist out there whose name is Pat Sheridan. He

is a total maniac. I saw him do Flight of the Bumble Bee

at the Midwest Band Clinic a few years ago. He was dressed in a

black leotard with yellow stripes around his middle, and he wore two little

pointy antennae, and he did Flight of Bumble Bee. He was

in front of the orchestra. He’s rather hefty, bigger than I am,

so he was pushing I’m sure 320-350 pounds. He was simultaneously

dancing and playing Flight of the Bumble Bee faster than you’ve

heard any flute player. It was just unbelievable.

BD: [Gently protesting] But that’s

just a gimmick, isn’t it?

Pokorny: It’s a

gimmick, but it was great music. He sold the product. He’s

a great salesman. In a way he’s kind of like Liberace. I

went to a Liberace concert, and I tell you, this guy was a showman. By

the end of those two and a half hours, he could have said, “Throw

your clothes off and come on stage,” or, “Throw

me your hotel key,” or, “Throw

me your wallet.” He had people eating right

out of the palm of his hand. He knew exactly what to do. It’s

the same type of charisma that Bruce Springsteen has on a crowd.

Whatever you think of his music, he’s a showman.

BD: When you’re playing in a band or

an ensemble or in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, how much is art and

artistry, and how much is show?

Pokorny: It all depends on the repertoire

we’re doing, but I’ve got to go in there pretty cool. I’ve got

to just get through the technical areas of doing what most of the

tuba parts are, which means basically wattage production. There

are not very many times where I’ll actually have a solo. Certainly,

when there is a bel canto section that can imitate singing,

there’s a lot of little melodic things in there that you can play.

You can be a little bit more expressive when you’re playing some Wagner

Overtures, or something like that. You have to be a little bit

more concerned with what you’re playing to exactly get things in tune.

If you’re playing the third of the chord, make sure you’re a little

lower to agree with the ‘just’

intonation as opposed to the ‘well-tempered’

tuning. If it’s the fifth of the chord, make sure it’s a little

bit higher. These are more technical aspects, but as far as actually

selling the musical product, I hope I don’t look bored when I’m up on

stage, because I hardly am. I don’t know exactly what we’re all

supposed to do when we’re on stage and people are watching us. Generally,

I try to ignore the audience, not because I think they should be ignored,

but there’s just a higher calling, and it’s on the music stand in front

of me. After the last note, I may relax enough to look into the hall

and see the audience.

BD: You don’t want to be distracted

by them.

Pokorny: Yes, that’s part of it. I

remember early on, when I first got the job in the orchestra here,

just before we were about to start, my buddy Charlie would say to

me, “Hey, look, Jake’s here tonight!” For me, that was absolutely

useless information. That was just something to distract me, because

it’s hard enough to just go ahead and play the job, and to do it right,

without realizing that someone who knows exactly what you’re supposed to

be doing the way you’re supposed to be doing it is sitting out there listening

to every note you’re trying to play. So, I turned to Charlie and

said (with mock anger), “Please don’t ever tell me that!!!” If I

see Jake afterwards, or if I see a bunch of tuba players afterwards,

that’s fine. It’s not a problem, and that’s great, but I don’t

need to know that stuff before. I know people are out there listening,

and they’re checking and watching, and maybe even counting up the mistakes.

But I also have to realize that the tuba part is not the most

important thing that’s going on. I’ve got to make sure that I’m

laying down the foundation for whatever else is happening above me.

Generally, it’s always happening above me, and I must be sure there’s

a good foundation underneath that is supporting the melody, and that

things are in tune.

BD: Are there times you have to work

carefully with the contrabassoon or the contrabass clarinet?

Pokorny: There are times when we have passages

together that I’ll have to go ahead and check intonation. There

are probably more with the trombone section because a lot of times we’ll

have stuff together. Then we can go ahead and actually tune our

chords, not to a well-tempered scale, but to a meantone scale, and getting

things so they just lock in really well. A highlight of a Brahms

symphony is to listen to our trombone section do one of those chorales.

It’s what impresses me. That’s worth the price of admission right

there to listen to those guys.

BD: You’re in the Chicago Symphony. Is

this where you want to be at this point in your career?

Pokorny: It better be! [Laughs] Otherwise,

I’ve been in the wrong place for 13 years now. This is a great

job. It’s a very good orchestra, having been here since 1989. I

had my one year in LA in the middle of all that in the ’92-’93 season...

BD: [Being chauvinistic about The Windy

City] Why did you do that???

Pokorny: [Smiles] LA is home.

I don’t need a map for that place. Among other places I’ve

been to — Tel Aviv, St. Louis,

Salt Lake City — I’ve used

maps. I’ve got file drawers full of maps. As far as LA, it

was good to go home and to be with the people who essentially brought

me up, my brass roots.

BD: I remember during that season we

were a little nervous. All of a sudden there was a little star by

your name in the program book saying ‘On Leave of

Absence’. Many of us said, “Wait a minute.

We don’t want this. This is not good.”

Pokorny: It was a mixed decision

as to whether to come back. I’d grown up with the Los Angeles

Philharmonic. That’s the orchestra I heard when I was in college,

and before college, and I know a lot of the players in the orchestra.

I would go to the Hollywood Bowl in the summer time as a spectator,

now I was a bona-fide member of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and I was

playing with my teachers! [Musing] Plus, 68 degrees in the

middle of January, after our morning rehearsal sitting outside under

a palm tree is not the worst type of life. But there is a real

fire in the belly out here in Chicago, and it seemed to be the right

decision to return. I also had met my future wife just before leaving

Chicago. So, I got married soon after I came back to Chicago in

1993. [Musing again] But when that Sears Tower fades in the

background as I’m driving West, I’m headed for the land of surf and sun

and mountains...

BD: [Getting caught up in the image]

Do you play your tuba on a surf board?

Pokorny: I don’t swim. [Has a

huge laugh] How’s that for a grand admission

— a Californian that doesn’t swim! [Laughter

all around]

* * * *

*

BD: Let me ask a real easy question. What’s

the purpose of music?

Pokorny: I think it’s to give people

some solace, inspiration, cause them to think about things maybe a

little more deeply and more life-changing than what they would normally

encounter in everyday life. Some people go through life, and

the most important goal in their life is to get a seat on the train when

they’re going to work. On the other hand, if people listen to music,

and it can get them into another place in their imagination or psyche, then

I think music has done some good for them. Maybe it can get them to

think more about their inner-self. That could be one of the purposes,

anyway. As a performer, it brings back the ultimate communication

with the people that you’re playing with. It’s

the ultimate team work. You have to play together, otherwise it’s

going to sound bad. Being an independent agent in an orchestra does

not work. I don’t

think it works in the business world either, but I really don’t

know that. But if you’re playing in an ensemble, you’ve

got to put all those differences behind you and make something great

happen together. Maybe it’s only going to be those 41 minutes during

a Dvořák 9th Symphony, and it stops the second after you

stop the last note, but at least you’re in an ensemble, and you get that

idea of playing together.

BD: That’s how you all make

it work.

BD: That’s how you all make

it work.

Pokorny: Yes. You have to make

it work, otherwise you’re just a bunch of soloists, and in an ideal

world it shouldn’t be about that.

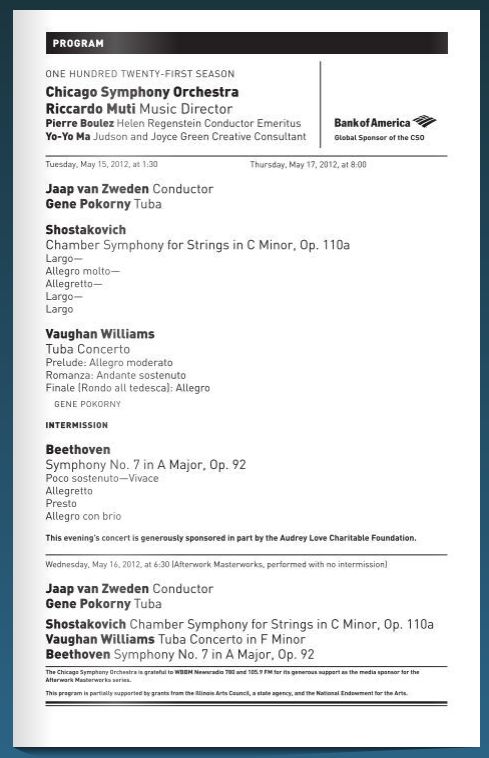

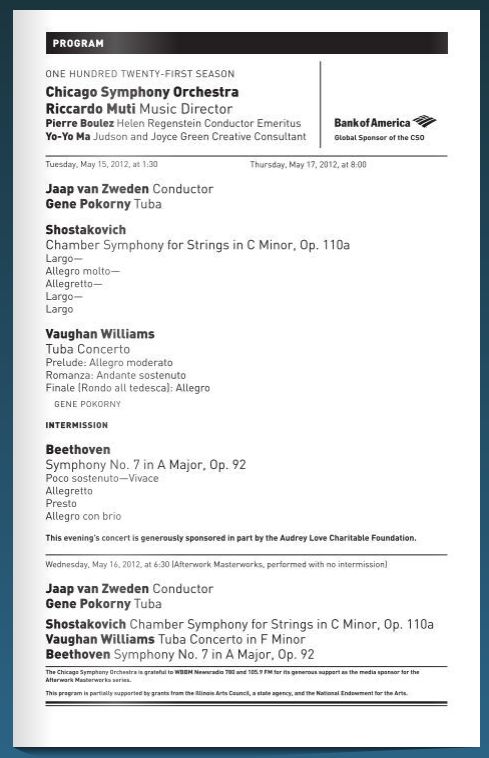

BD: Is the music that you play for everyone?

[Vis-a-vis the program shown at left, see my interviews with

Pierre Boulez.]

Pokorny: I like to believe that it’s for a

lot more people than we usually see. If we sold out every concert

of the Chicago Symphony, that comprises a very small percentage of the

population of the Greater Chicago area. I would like to believe that

there are more people that might find a little bit of beauty, a little

bit of inspiration, that have connection with what we’re doing here.

BD: [Knowing that he is a big fan of

The Three Stooges] How do we get more Stooge fans into orchestra

hall?

Pokorny: They’re ‘victims

of soicumstances’.

[Both laugh] One of the things that is really important

is the aspect of education. A lot of people are simply not exposed

to it. This problem started a whole long time ago. It was

in the ’60s and ’70s when music

education started to get really cut out of the public schools.

We didn’t recognize it as such a big problem back then, because problems

like that take 20 years to germinate. Now we have a population of

young people in their late 20s 30s, who have brilliant minds and are into

a lot of different things. But when it comes to appreciating not

just music, but the fine arts — such

as Shakespeare and other theater, and even going to mime performance

— there’s just not that much interest in

stuff like that. Their idea of culture is watching reruns of Seinfeld,

or Gilligan’s Island, or the World Wrestling Federation.

It just doesn’t get too much beyond that. It’s almost a ghetto

mentality without the arts.

BD: It’s ironic, because now, with

records and CDs and cable and satellite and all of these new things

on the internet, we have more dissemination than ever before.

Pokorny: Yes. There’s so much

more, but there are so many more possibilities that it can be a little

confusing. It might be that there are just too many choices.

If there was the exposure in school, and if they could not only

listen but also participate, even if they end up being an accountant

or something like that later on in life, that’s fine. At least

they would have had the experience of sitting in a section and doing

something like that. They might appreciate some of the music if

they were exposed to some of the literature in a school band or orchestra

program. Then they could come out and hear the orchestra play. There’s

one thing that got started in Mount Prospect a few years ago. We’ve

all heard of the Do-It-Yourself Messiah, which got started here

in Chicago many years ago. Well, not so long ago, something got

started in Mount Prospect, Illinois with the Mount Prospect Concert

Band, called Do-It-Yourself Sousa. They set about putting

together two different rehearsals in two different weeks. Basically,

anybody who played an instrument in junior high or high school, and had

given it up while they went to college and gotten into their profession

and started a family, could get their instruments out, dust them off, and

get them to come to a joint rehearsal with Mount Prospect Concert Band,

and they had a Do-It-Yourself Sousa Concert. They do not only Sousa,

but some Broadway show tunes, and some British military marches, and perhaps

some other music. It would happen on a Sunday concert in the park.

BD: How many people do they get

— several hundred?

Pokorny: Quite a number of people would

come out of the woodwork, and some of these people would have so much

fun doing it that they would continue on as regular members of the Mount

Prospect Concert Band. In the really old days, that’s why the string

quartet concerts were so popular. People did play the violin or

the cello at home, and they would get together as amateurs. So, when

a professional string quartet did come to town, all of a sudden there was

a group that they could empathize with because they were doing the same

stuff. They could appreciate the artistry that was going into a performance.

It’s very much the same way when people sit around on a Saturday or Sunday

afternoon to watch golf on television. It’s not so much that the

television picture is so good, and that it’s so enthralling. The

reason people watch is that they can empathize with those who are trying

to hit the ball into a small hole, because they have tried to do it themselves.

They appreciate how tough it is. So, when a guy like Tiger Woods

is out there, they want to see it because they can empathize with how much

skill, craftsmanship, and luck it takes to attain what he’s attained. They

can relate to that.

BD: So, you get guys that want to come

and play?

Pokorny: Yes. This is what happens

in Mount Prospect, with the Do-It-Yourself Sousa. I hope this catches

on all around. It will take a while. Occasionally, when

the CSO brass section plays, or when just the low brass section plays,

there are a lot of people who attend. It’s kind of surprising for

the people in the administration here. When we first gave concerts,

the administration was very surprised at how many people showed up. They

expected maybe 80% of the house to be filled, but the place was packed!

When the trombone players and myself played our first chamber music

concert 12 years ago, we had to turn 200 people away from the ballroom.

The next concert they moved us to the main stage, and they didn’t print

enough programs. This is a good type of administrative problem,

when you have many more people show up than are expected. Hopefully

people will find that listening to music is something that is worth the

effort. Mitch Miller used to say that for the price of a bad movie,

you can go out and hear some pretty good music played by a world class

ensemble. Maybe it costs a little bit more than the price of a bad

movie these days, but still the live performance is much better and more

exciting than what you get on a CD, because sound is not just what you’re

hearing. It’s also the seismic

sound of just feeling this music. When I go out there

and play some notes, I try to make a whole lot of other people feel

really good. There’s something for everybody. You never know

what’s going to happen in a live performance.

BD: For 25 years I made my living playing

CDs on the radio, but I was always telling people to go to the live

concerts.

Pokorny: That’s the best way to be.

BD: Thank

you for sharing your artistry here in Chicago. We appreciate

it.

Pokorny: I appreciate it, too. It’s

a great town to play in.

========

========

========

---- ---- ----

======== ========

========

© 2002 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in a rehearsal room backstage at Orchestra

Hall on June 13, 2002. Portions were broadcast on WNUR later that

year, and again in 2012,

and 2019. This transcription was made in

2021, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website,

click here. To

read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few

other interesting observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce

Duffie was with WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975 until its

final moment as a classical station in February

of 2001. His interviews have also appeared

in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he

now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his

website for more information

about his work, including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus a full list of his

guests. He would also like to call your attention

to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

BD: Can I assume that something these records

would coincide with the excerpt book that each performer has practiced

before going to auditions?

BD: Can I assume that something these records

would coincide with the excerpt book that each performer has practiced

before going to auditions? Pokorny: Yes, but in the wrong way. I was

pressing the mouthpiece into my lips with too much force, and also using way

too much air pressure. I just got off on the wrong foot. My

dad was so upset at the way I was approaching the trumpet that he said,

“Why don’t you take up something else, like saxophone,” which I did.

I went to saxophone and, eventually, clarinet. It was probably

my second year in junior high when they needed somebody to play tuba,

so I picked up the tuba which was a better fit than a trumpet as a brass

instrument for me.

Pokorny: Yes, but in the wrong way. I was

pressing the mouthpiece into my lips with too much force, and also using way

too much air pressure. I just got off on the wrong foot. My

dad was so upset at the way I was approaching the trumpet that he said,

“Why don’t you take up something else, like saxophone,” which I did.

I went to saxophone and, eventually, clarinet. It was probably

my second year in junior high when they needed somebody to play tuba,

so I picked up the tuba which was a better fit than a trumpet as a brass

instrument for me.

Pokorny: That’s already been done! There

is this one tuba soloist out there whose name is Pat Sheridan. He

is a total maniac. I saw him do Flight of the Bumble Bee

at the Midwest Band Clinic a few years ago. He was dressed in a

black leotard with yellow stripes around his middle, and he wore two little

pointy antennae, and he did Flight of Bumble Bee. He was

in front of the orchestra. He’s rather hefty, bigger than I am,

so he was pushing I’m sure 320-350 pounds. He was simultaneously

dancing and playing Flight of the Bumble Bee faster than you’ve

heard any flute player. It was just unbelievable.

Pokorny: That’s already been done! There

is this one tuba soloist out there whose name is Pat Sheridan. He

is a total maniac. I saw him do Flight of the Bumble Bee

at the Midwest Band Clinic a few years ago. He was dressed in a

black leotard with yellow stripes around his middle, and he wore two little

pointy antennae, and he did Flight of Bumble Bee. He was

in front of the orchestra. He’s rather hefty, bigger than I am,

so he was pushing I’m sure 320-350 pounds. He was simultaneously

dancing and playing Flight of the Bumble Bee faster than you’ve

heard any flute player. It was just unbelievable. BD: That’s how you all make

it work.

BD: That’s how you all make

it work.