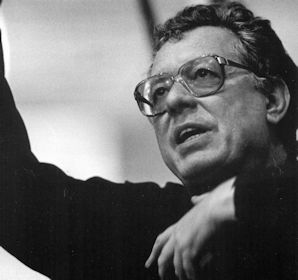

Harry Alfred Robert Kupfer (August 12, 1935 – December 30,

2019) was a German opera director and academic. A long-time director

at the Komische Oper Berlin, he worked at major opera houses and at

festivals internationally. Trained by Walter Felsenstein, he worked

in the tradition of realistic directing. At the Bayreuth Festival,

he staged Wagner's Der fliegende Holländer in 1978

and Der Ring des Nibelungen in 1988. At the Salzburg Festival,

he directed the premiere of Penderecki's

Die schwarze Maske in 1986, and Der Rosenkavalier by

Richard Strauss in 2014.

Born in Berlin, Kupfer studied theater at the Theaterhochschule

Leipzig from 1953 to 1957. He was the assistant director at the Landestheater

Halle, where he directed his first opera, Dvořák's Rusalka,

in 1958. From 1958 to 1962, he worked at the Theater Stralsund, then

at the Theater in Karl-Marx-Stadt, from 1966 as opera director at the

Nationaltheater Weimar, also lecturing at the Hochschule für Musik

Franz Liszt, Weimar from 1967 to 1972. In 1971, he staged as a guest at

the Staatsoper Berlin Die Frau ohne Schatten by Richard Strauss.

Born in Berlin, Kupfer studied theater at the Theaterhochschule

Leipzig from 1953 to 1957. He was the assistant director at the Landestheater

Halle, where he directed his first opera, Dvořák's Rusalka,

in 1958. From 1958 to 1962, he worked at the Theater Stralsund, then

at the Theater in Karl-Marx-Stadt, from 1966 as opera director at the

Nationaltheater Weimar, also lecturing at the Hochschule für Musik

Franz Liszt, Weimar from 1967 to 1972. In 1971, he staged as a guest at

the Staatsoper Berlin Die Frau ohne Schatten by Richard Strauss.

Kupfer was opera director at the Staatsoper Dresden from 1972 to

1982. In 1973, he staged abroad for the first time: Elektra

by Richard Strauss at the Graz Opera. He was from 1977 professor at

the Hochschule für Musik Carl Maria von Weber Dresden. In 1978,

he was invited to direct Der fliegende Holländer at

the Bayreuth Festival, conducted by Dennis Russell Davies.

He staged the story in a psychological interpretation as the heroine

Senta's imaginations and obsessions.

Kupfer was chief director at the Komische Oper Berlin from 1981,

ane simultaneously, he was professor at the Hochschule für Musik

"Hanns Eisler" in Berlin. At the opera, he staged Mozart operas in

the order of their composition, including Die Entführung aus

dem Serail in 1982 and Così fan tutte in 1984. He

also staged there Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

in 1981, Puccini's La Bohème in 1982, Reimann's Lear,

Verdi's Rigoletto and Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov in 1983,

among many others. He directed there the premiere of Judith by

Siegfried Matthus. In 1988, he staged at the Bayreuth Festival Wagner's

Der Ring des Nibelungen,

Kupfer premiered several operas, including Udo Zimmermann's Levins

Mühle at the Staatstheater

Dresden in 1973, conducted by Siegfried Kurz. He staged the GDR premiere

of Schönberg's Moses und Aron there, also conducted by

Kurz in 1975. In 1979, he directed there the world premiere of Zimmermann's

Der Schuhu und die fliegende Prinzessin, conducted by Max

Pommer, also the premiere of Georg Katzer's Antigone oder die Stadt

at the Komische Oper Berlin in 1991, conducted by Jörg-Peter Weigle,

the musical Mozart by librettist Michael Kunze and composer Sylvester

Levay at the Theater an der Wien in 1999, conducted by Caspar Richter, and

in 2000 Reimann's Bernarda Albas Haus, at the Bavarian

State Opera, conducted by Zubin Mehta. Kupfer

co-wrote the libretto with composer of Penderecki's opera Die schwarze

Maske. He directed the 1986 world premiere production in Salzburg

and the US premiere production at the Santa Fe Opera in 1988.

Kupfer and his wife, the music teacher and soprano Marianne Fischer-Kupfer, had

a daughter, Kristiane, who is an actress.

He died on 30 December 2019 in Berlin.

* * *

* *

Götz Friedrich (August 4, 1930 in Naumburg, Germany

– December 12, 2000 in Berlin, Germany) was a German opera and theatre

director.

Götz Friedrich (August 4, 1930 in Naumburg, Germany

– December 12, 2000 in Berlin, Germany) was a German opera and theatre

director.

He was a student and assistant of Walter Felsenstein at the Komische

Oper Berlin in (East) Berlin, where he went on to direct his early

productions. He first came to international prominence with a controversial

1972 production of Wagner's Tannhäuser at Bayreuth. He defected

to the West whilst working on a production of Jenůfa in Stockholm

later the same year.

From 1972 to 1981 he was principal director at the Hamburg State

Opera. Between 1977 and 1981, he was also director of productions at

the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden in London, where he staged the

first British performances of the three-act completion of Berg's

Lulu. In 1981 he took up the post of general director of the

Deutsche Oper Berlin where he stayed until his death in 2000, staging

productions across the whole of the operatic repertoire.

He was particularly known for his productions of Wagner. He staged

his first production of the Ring at Covent Garden (1973–76,

conducted by Colin Davis). The designs by Josef Svoboda centred on

a revolving hydraulic platform. In the 1980s he directed a new production

for the Deutsche Oper in Berlin (the so-called 'Time Tunnel' Ring).

Covent Garden later imported this production to replace a planned production

by Yuri Lyubimov, which had been abandoned after Das Rheingold.

Bernard Haitink

conducted complete cycles of the second Friedrich Ring, in 1992.

The production was also staged in Washington and Japan.

In 1976 he directed the world première of Josef Tal's Die

Versuchung (The Temptation) in Munich. He directed the world

premières of Luciano Berio's Un re in ascolto, Ingvar

Lidholm's "Ett Drömspel" and Henze's Raft of

the Medusa.

He was the initiator of The American Berlin Opera Foundation

(ABOF, now named The Opera Foundation), located in New York

City.

* * *

* *

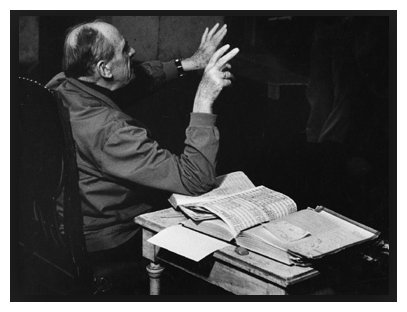

Walter Felsenstein (May 30, 1901 – October

8, 1975) was an Austrian theater and opera director. He was

one of the most important exponents of textual accuracy, and gave

productions in which dramatic and musical values were exquisitely researched

and balanced. In 1947 he created the Komische Oper in East Berlin,

where he worked as director until his death.

Walter Felsenstein (May 30, 1901 – October

8, 1975) was an Austrian theater and opera director. He was

one of the most important exponents of textual accuracy, and gave

productions in which dramatic and musical values were exquisitely researched

and balanced. In 1947 he created the Komische Oper in East Berlin,

where he worked as director until his death.

Preparations for each new production could last two

months or longer. If singers meticulously coached and trained

in their parts fell ill, performances were simply canceled.

Since the glamorous superstars of the day could never spare the time

Felsenstein required, he worked with his own hand-picked troupe of

devoted singers, most from Eastern Europe and virtually unknown in

the West. Everything was sung in German, usually in his own translations.

Whoever wanted to experience this singular operatic mix had to make

the pilgrimage to East Berlin, a trip that became even dicier after the

wall went up.

Together with the Komische Oper troupe he visited the

USSR a few times. In Moscow it was stated that his way of the

opera staging was similar to the principles of Konstantin Stanislavsky.

His most famous students were Götz Friedrich and Harry Kupfer,

both of whom went on to have important careers developing Felsenstein's

work. |

Born in Berlin, Kupfer studied theater at the Theaterhochschule

Leipzig from 1953 to 1957. He was the assistant director at the Landestheater

Halle, where he directed his first opera, Dvořák's Rusalka,

in 1958. From 1958 to 1962, he worked at the Theater Stralsund, then

at the Theater in Karl-Marx-Stadt, from 1966 as opera director at the

Nationaltheater Weimar, also lecturing at the Hochschule für Musik

Franz Liszt, Weimar from 1967 to 1972. In 1971, he staged as a guest at

the Staatsoper Berlin Die Frau ohne Schatten by Richard Strauss.

Born in Berlin, Kupfer studied theater at the Theaterhochschule

Leipzig from 1953 to 1957. He was the assistant director at the Landestheater

Halle, where he directed his first opera, Dvořák's Rusalka,

in 1958. From 1958 to 1962, he worked at the Theater Stralsund, then

at the Theater in Karl-Marx-Stadt, from 1966 as opera director at the

Nationaltheater Weimar, also lecturing at the Hochschule für Musik

Franz Liszt, Weimar from 1967 to 1972. In 1971, he staged as a guest at

the Staatsoper Berlin Die Frau ohne Schatten by Richard Strauss.

Götz Friedrich (August 4, 1930 in Naumburg, Germany

– December 12, 2000 in Berlin, Germany) was a German opera and theatre

director.

Götz Friedrich (August 4, 1930 in Naumburg, Germany

– December 12, 2000 in Berlin, Germany) was a German opera and theatre

director.  Walter Felsenstein (May 30, 1901 – October

8, 1975) was an Austrian theater and opera director. He was

one of the most important exponents of textual accuracy, and gave

productions in which dramatic and musical values were exquisitely researched

and balanced. In 1947 he created the Komische Oper in East Berlin,

where he worked as director until his death.

Walter Felsenstein (May 30, 1901 – October

8, 1975) was an Austrian theater and opera director. He was

one of the most important exponents of textual accuracy, and gave

productions in which dramatic and musical values were exquisitely researched

and balanced. In 1947 he created the Komische Oper in East Berlin,

where he worked as director until his death.

The success of this production opened the way to the Gartnerplatztheater

in Munich (“The Queen of Spades” by Pyotr Tchaikovsky, “Duke Bluebeard‘s

Castle” by Bela Bartok), and then to the Metropolitan Opera in New

York (“The Queen of Spades” (first performance there in Russian), “Boris

Godunov” by Modest Mussorgsky, “Aida” and “Macbeth” by Giuseppe Verdi,

“Cosi Fan Tutte” by Wolfgang A. Mozart). In 1969-1973 he was the director

and artistic manager of the Polish Radio and Television Great Symphony

Orchestra in Katowice. From 1977 to 2001, he was the director and

artistic manager of the National Philharmonic in Warsaw. Together

with the National Philharmonic‘s ensemble, he went on a number of large

tours in Europe, the United States, Australia, China and Japan as

well as making numerous radio and CD recordings. During that time,

he was also a conductor of the Sudwestfunk Orchestra in Baden-Baden

(1980-1986). He has performed with many famous orchestras in Leningrad,

Cleveland, Chicago (debut at Ravinia in 1973), Cincinnati,Pittsburgh,

Detroit, Tokyo, Toronto (1974 – a European tour with the Toronto Symphony

Orchestra after the demise of Karel Ancerl), London, Prague, Munich,

Stuttgart, Rome, Milan, Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin, Frankfurt, Athens. He

was Principal Guest Conductor and Music Advisor of the Pacific Symphony

of Orange County, California (USA) for their 1989–1990 season.

The success of this production opened the way to the Gartnerplatztheater

in Munich (“The Queen of Spades” by Pyotr Tchaikovsky, “Duke Bluebeard‘s

Castle” by Bela Bartok), and then to the Metropolitan Opera in New

York (“The Queen of Spades” (first performance there in Russian), “Boris

Godunov” by Modest Mussorgsky, “Aida” and “Macbeth” by Giuseppe Verdi,

“Cosi Fan Tutte” by Wolfgang A. Mozart). In 1969-1973 he was the director

and artistic manager of the Polish Radio and Television Great Symphony

Orchestra in Katowice. From 1977 to 2001, he was the director and

artistic manager of the National Philharmonic in Warsaw. Together

with the National Philharmonic‘s ensemble, he went on a number of large

tours in Europe, the United States, Australia, China and Japan as

well as making numerous radio and CD recordings. During that time,

he was also a conductor of the Sudwestfunk Orchestra in Baden-Baden

(1980-1986). He has performed with many famous orchestras in Leningrad,

Cleveland, Chicago (debut at Ravinia in 1973), Cincinnati,Pittsburgh,

Detroit, Tokyo, Toronto (1974 – a European tour with the Toronto Symphony

Orchestra after the demise of Karel Ancerl), London, Prague, Munich,

Stuttgart, Rome, Milan, Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin, Frankfurt, Athens. He

was Principal Guest Conductor and Music Advisor of the Pacific Symphony

of Orange County, California (USA) for their 1989–1990 season.