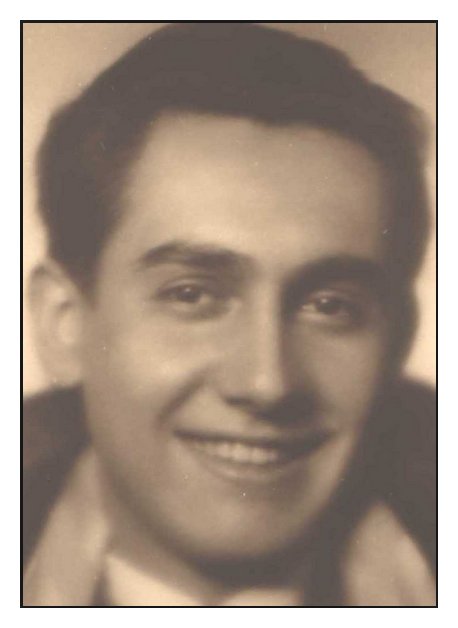

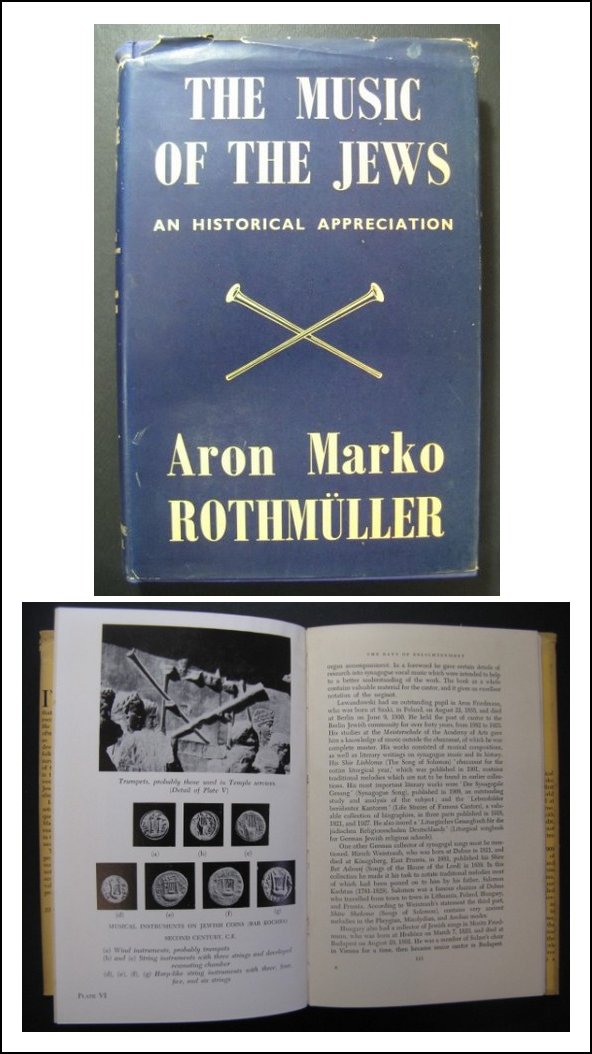

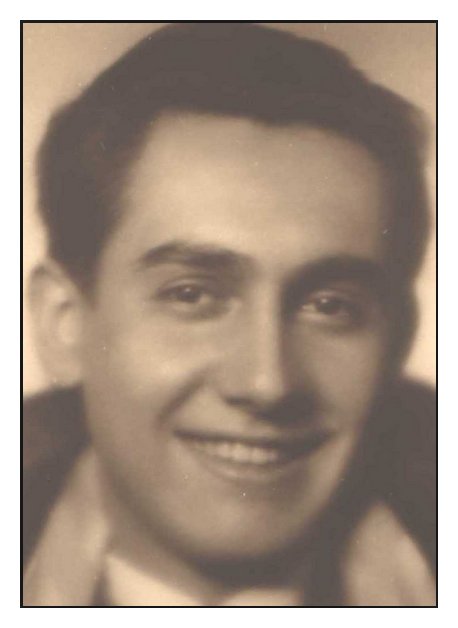

Baritone / Author Marko Rothmüller

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

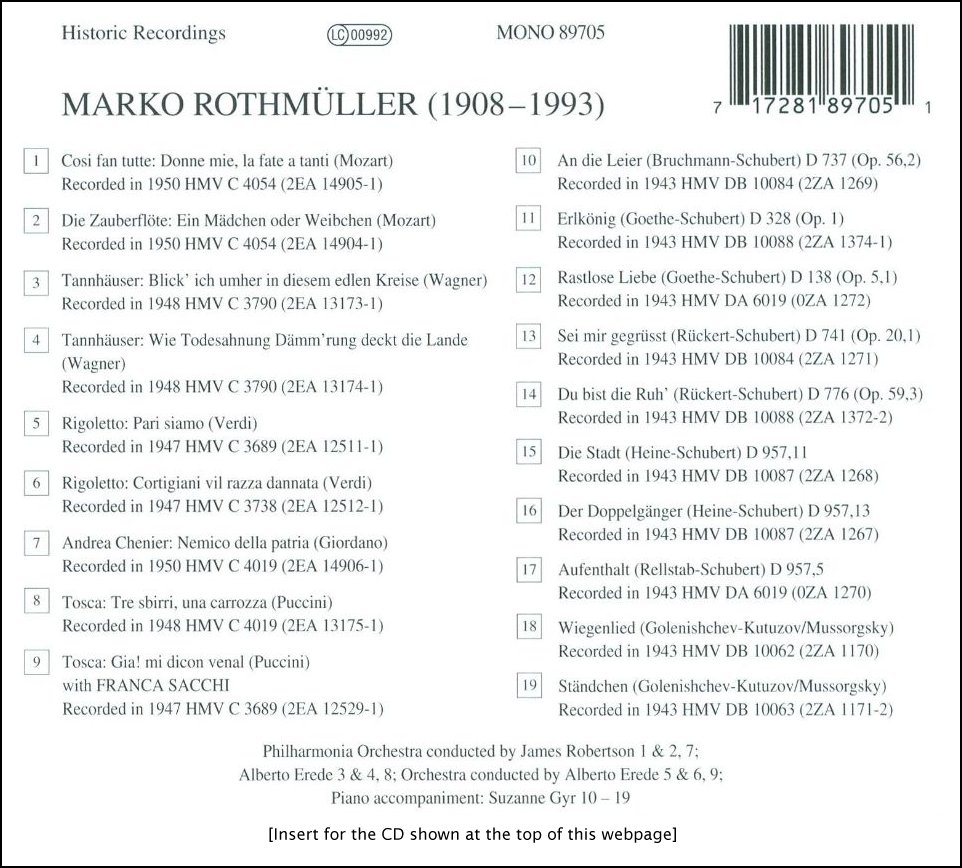

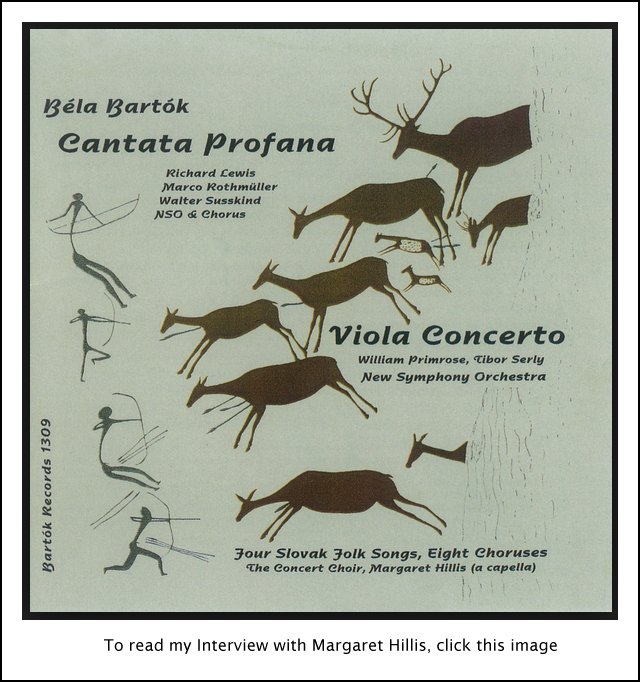

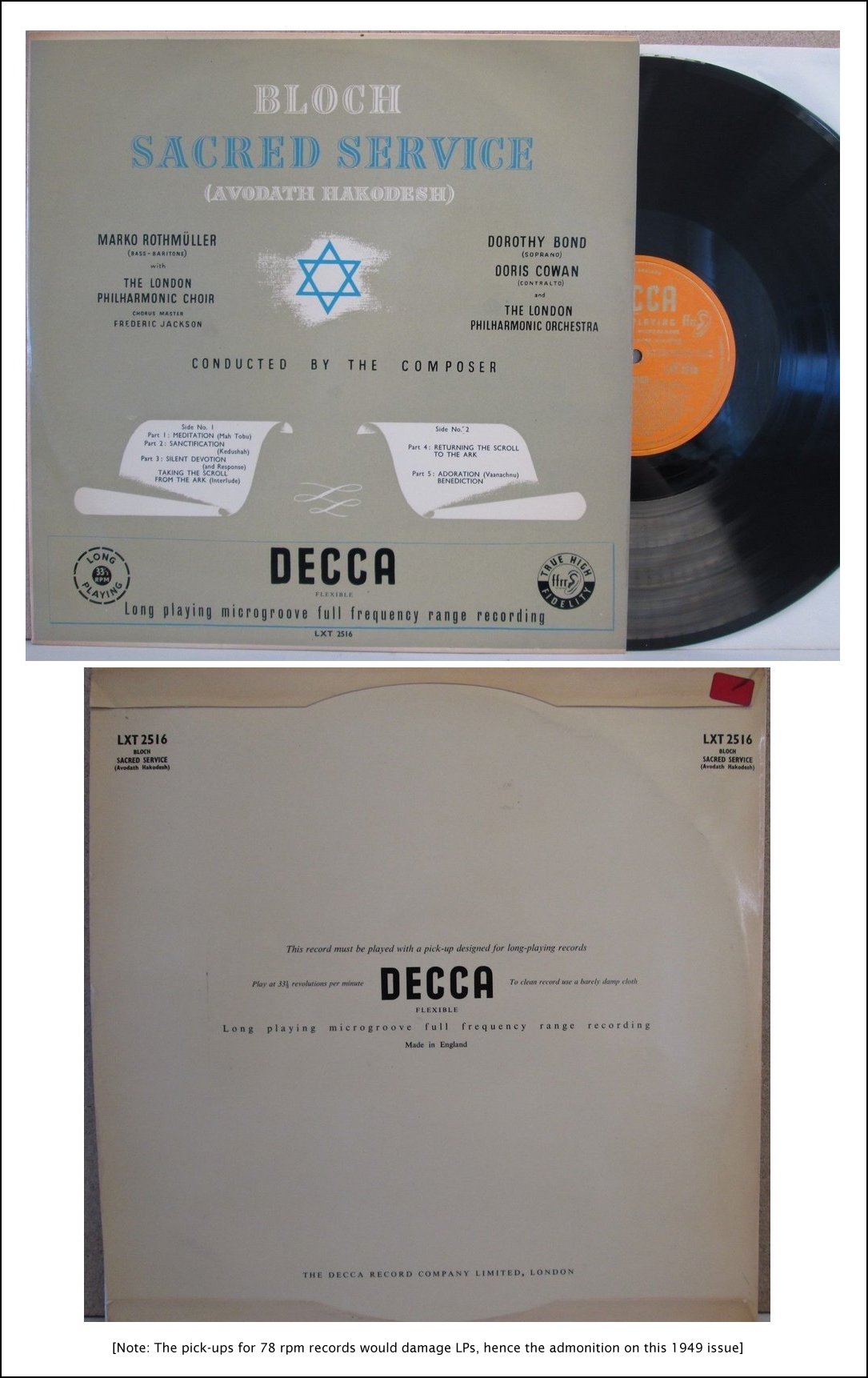

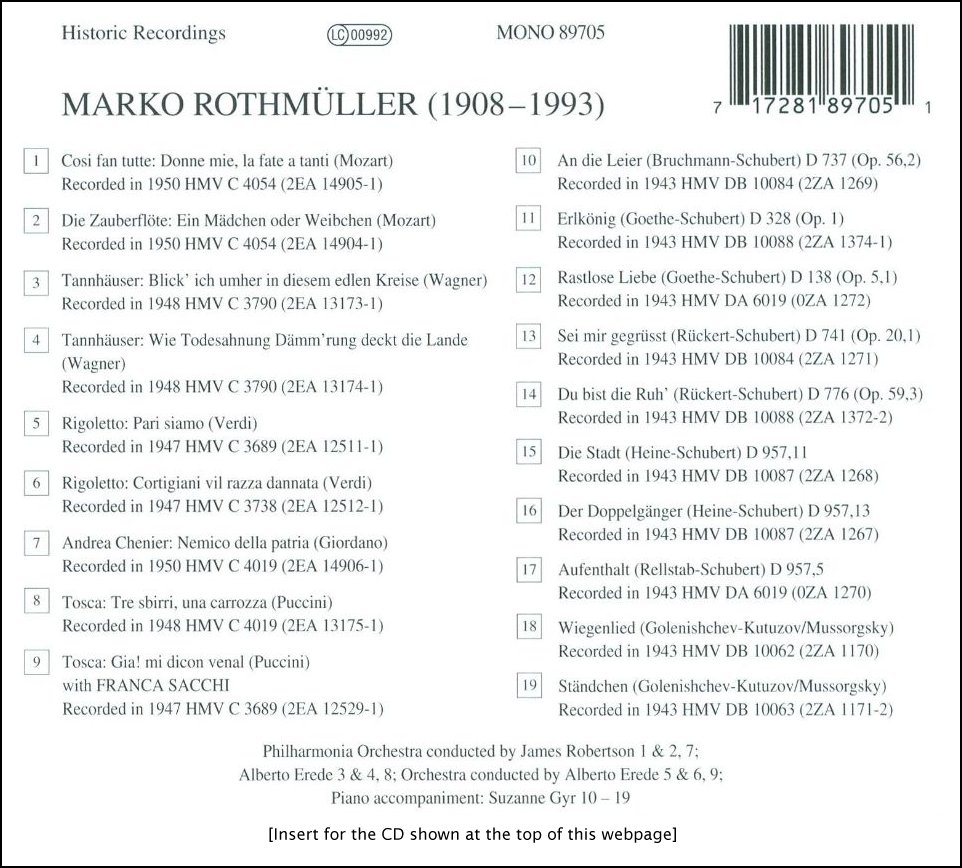

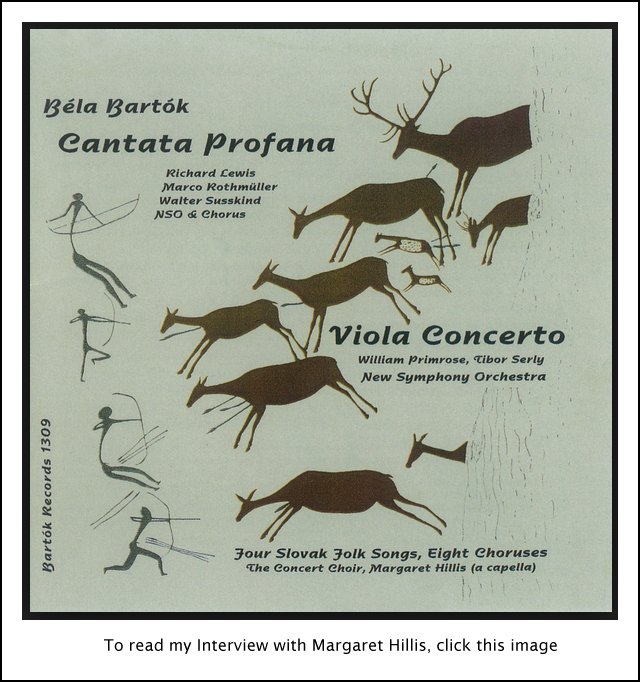

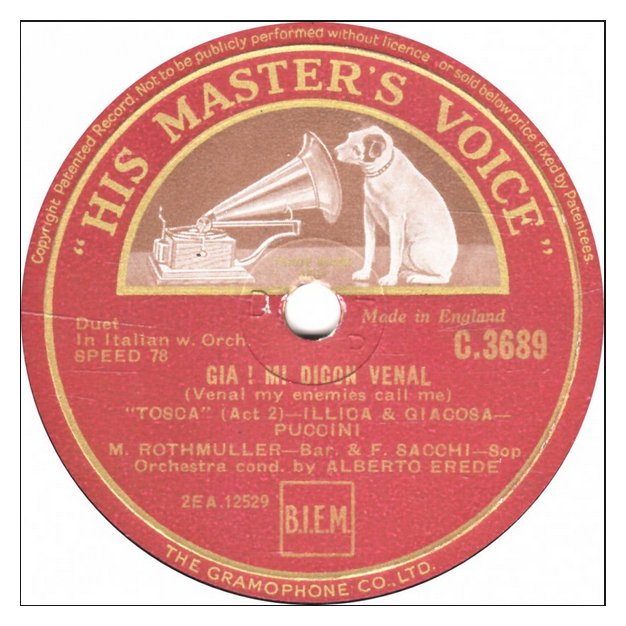

[List of what is on this CD appears at the bottom of this webpage.]

[Another, more comprehensive biography (in German) also appears at the bottom

of this webpage.]

In the spring of 1985, I made contact with Rothmüller, and he graciously

allowed me to call him on the phone for a conversation. He was very

straight-forward about discussing the topics I suggested, and we spent a

wonderful hour together.

Names which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my site.

Also, note the distinction between, for instance, Rigoletto (the opera by Verdi) and Rigoletto

(the character in the opera).

Here is what transpired at that time . . . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You

have been teaching at the Indiana University?

Marko Rothmüller:

Correct, for twenty-four years. The first seven or eight years I still

sang with some opera houses, like Vienna and the Metropolitan and Zürich,

so I had leaves and wasn’t always in Bloomington.

BD: The University

was OK with your going back and forth?

MR: Oh, they liked that here. They like to

have an active artist. We have Starker, for instance,

and Pressler, and

many people who concertize all over the world.

MR: Oh, they liked that here. They like to

have an active artist. We have Starker, for instance,

and Pressler, and

many people who concertize all over the world.

BD: Then when they

come back home, they do a little teaching?

MR: Yes.

We always have to make up missed lessons, of course. [Laughs]

For instance, when I was with the Met, we never had rehearsal after Friday

Noon usually until Tuesday. So I would fly back to Bloomington on Friday

to teach over the weekend, and Monday night I would fly back to New York.

BD: Was that too

much for you?

MR: Oh, no.

It was a flight of two hours or so, which is not too bad. I enjoyed

teaching and I enjoyed singing. Music is my world.

BD: You’ve been

involved with young singers for a long time. Are the young singers

today prepared in the same way, or differently than they were thirty, forty,

fifty years ago?

MR: Not only here,

but in general, the whole attitude is a different one, partly because the

requirements are different. What we call bel canto repertory, when that is done,

it is not done the same way as before. Even at my generation, we used

to try to sing it as beautifully as possible, and many of the parts where

not so important as acting parts. I’m not talking of Rigoletto or Scarpia,

but the beauty and the technical evenness was very important, and everything

else was considered inferior. At least to my knowledge, only

a few artists are of that kind today.

BD: Is this a good

thing or a bad thing?

MR: Oh, it’s very

bad for two reasons. It’s bad whenever a work is performed which was

written for bel canto

— with beautiful singing — and also that

the contemporary singers often have to sing parts which are not written for

beautiful singing, and don’t require the technique which was worked especially

in Italy for about four to six hundred years. There are vocal requirements

which are a different kind, therefore the voices are often ruined too soon.

BD: At what point

in compositional time did we lose the idea of beautiful singing?

MR: I would say

this was mainly after the Second World War. Even with the Richard Strauss

works, and Hindemith, and Wozzeck,

one was still expected, wherever possible, to sing a beautiful vocal line,

a musical line, and have a wonderful phrasing, and so on. Now this

is not so, even when I listen to the top singers. I know the whole

repertoire, and not only my parts. You can notice how often these people

bring it, and if you bring it more often than good phrasing would require,

it’s inferior in this regard.

BD: It breaks up

the line?

MR: Yes, it breaks

up the line! That’s exactly right. We don’t have that in the

instrumental-style of playing, except for the so-called contemporary music

with the electronics. Otherwise, our instrumentalists —

like Perlman or Starker, or any of those cellists or violinists

or pianists — still phrase, even when they play the

more or less contemporary composers like Shostakovich or Prokofieff.

So you see how phrasing is important. I can tell you a very amusing

thing. Many years ago I studied in Vienna, but then I went away.

After the War, I sang several years at the Vienna State Opera. First

I sang Rigoletto, and the second performance was The Barber of Seville. In the Rigoletto, people see me only in the

mask, and they wouldn’t recognize me if I am as I usually am.

BD: Plus you’re

all hunched over and everything.

MR:

Yes. So when I went to my dressing room for the Barber to change, a gentleman was there,

and asked if I was Mr. Rothmüller. I was the only one whom he

didn’t know, so he figured out that I must be the guest because at first

I was guest, and then I got a contract. He asked if I was a string

player. That was the first time somebody asked me that, and I was very

amused. I told him, “My main instrument is violin,

but I also played other instruments. Why do you ask?”

He said, “Because in the orchestra we had a discussion.

We were of the opinion that you phrase as a string player.”

String players are sensitive to such things, just as painters are sensitive

to a painting, and the others are not. So that was funny because the

phrasing is very important, and if you play an instrument, you learn it automatically

because you don’t have to breathe. You can phrase with the bow.

BD: Would you recommend

to all young singers that they study violin or cello for a year or two?

MR: This is always

a very good thing. I usually recommend people to play the piano because

that’s a very useful instrument, and in the piano you can learn all these

principles, too. Bernard Greenhouse [cellist with the Beaux Arts Trio] played

The Swan, and it was just one of

those times when it was thousand per cent perfect. The next morning

we were talking about it, and I said, “I always say

to my baritone students they should sing as a good cellist plays.”

Then he said to me, “That’s funny. I say to my

students they should play as a good baritone sings!”

BD: So each of

you were looking for the ideal in the other!

MR: There’s something

which should we should have in common. The moment you listen to a singer,

if you cannot compare it to any instrumental music-making, it’s not good.

A hundred and fifty years ago, if a soprano sang, you didn’t know sometimes

if it was an oboe or a soprano because they sang so instrumentally.

Also the production of the tone was a different before the Romantic period.

It was only in the Romantic period that they started the change. It

happened in instrumental music as well. Before that, the vocal music

was used to express a mood, with expressions of longing, love and such things.

So you had to give to the tone something in addition to just the pitch.

BD: Would it be

correct then to say that a hundred and fifty years ago every musician learned

musicianship, and then on top of that superimposed whatever technique they

were using, such as violin, or voice, or piano?

MR: You’re right

in this only that they landed at the same time. In the seventeenth

century, and especially in the eighteenth century, vocal training was whole-day

training. All day you would learn sight-singing, harmony, scales, staccati, trills, everything. It

was all day, and the days were longer. They didn’t quit at five o’clock!

[Both laugh]

BD: Right!

So have we really lost that tradition?

MR: Yes, but some

people will say we have gained other things. I personally disagree

because I like beauty. For me, I wouldn’t accept that, and when I sang

Wozzeck, I didn’t sing it as some people might. If you have an opportunity,

you can listen to the record of Wozzeck

with Fischer-Dieskau. There, every note is correct.

* *

* * *

BD: Speaking of

Wozzeck, you studied composition

with Alban Berg (1885-1935).

MR: Yes, I did. At that time I didn’t even

intend in the slightest to ever become a singer. During the time I

was in Vienna — before I came to him — I was

already a paid conductor of a choir. But before that, I also conducted

instrumentalists, and so on. My oldest brother, who took care of us

because we didn’t have a father anymore at that time, said I should also

take voice lessons because a voice teacher had said it would be a crime not

train my voice. So I had to do it, because otherwise I couldn’t understand.

It was only when I was with Berg for about three years that people heard

me, and I suddenly had success as a young singer. Then I figured if

I tried as a singer and didn’t succeed, I could always turn to conducting,

which I did. I conducted orchestras and my own compositions during

my life several times. Even in the last ten years in Bloomington, I

wrote for a play with music, and I conducted it myself. But if I started

to sing I didn’t succeed or I didn’t like it, then it is very difficult because

a voice is an instrument which you have to maintain.

MR: Yes, I did. At that time I didn’t even

intend in the slightest to ever become a singer. During the time I

was in Vienna — before I came to him — I was

already a paid conductor of a choir. But before that, I also conducted

instrumentalists, and so on. My oldest brother, who took care of us

because we didn’t have a father anymore at that time, said I should also

take voice lessons because a voice teacher had said it would be a crime not

train my voice. So I had to do it, because otherwise I couldn’t understand.

It was only when I was with Berg for about three years that people heard

me, and I suddenly had success as a young singer. Then I figured if

I tried as a singer and didn’t succeed, I could always turn to conducting,

which I did. I conducted orchestras and my own compositions during

my life several times. Even in the last ten years in Bloomington, I

wrote for a play with music, and I conducted it myself. But if I started

to sing I didn’t succeed or I didn’t like it, then it is very difficult because

a voice is an instrument which you have to maintain.

BD: When studying

with Berg, did he gave you ideas about how to compose?

MR: He taught very

much the same way as Schoenberg did. I would compare it to how a carpenter

teaches his apprentice. That is how he taught me.

BD: In studying

his teaching techniques and then studying his music, did you find that Berg

actually adhered to the kinds of things in his own music that he taught?

MR: Oh, sure!

The thing is he didn’t really teach. He taught only what he called

‘the strict style’. I didn’t go to him as a beginner. I had already

finished harmony very successfully. I had five years training at the

Academy, so I was already an expert in writing polytonal music. When

I was with Berg we went a little bit back, and then went through all these

things. When I asked him when we would work on modern counterpoint,

as we called it at that time, after a while he thought he understood me.

He said, “I would consider myself quite a contemporary

composer, but I wouldn’t know what to teach you. I can only teach you

the rules. Which rules you ignore or change is up to you.”

So I did learn the rules of the twelve-tone music, which he wrote, but he

didn’t insist on any style. I only wrote a few twelve-tone things.

BD: If you were

still writing music today, would you write in the style of Berg?

MR: No. I

composed a lot of music but it is always, I would say, kind of late Romantic.

He himself was always trying his music at the piano, and everything has to

sound. It has to make sense as a sound, not only look good on the paper.

Everybody notices that if you take these three composers — Schoenberg,

Webern and Berg — Berg is easier to listen to.

Webern most difficult than some of the others because it is too much the

other way.

BD: I’m trying

to figure out where composers in general went wrong.

MR: Oh, they didn’t

go wrong! I could tell you in very simple terms. If you take

the so-called Classic period of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, they didn’t

mind if they used a theme of anybody else and made something new out of it,

either as a variation or in a quartet. Haydn, and especially Beethoven,

even used folk tunes. The originality was first of all not required;

it was music which was required. But nowadays people try to do something

new with computer music, with electronic sounds. If you go to a recital

of so-called ‘contemporary music’, most of the time you hear sounds, or noises,

which you normally try to avoid. [Both laugh] If you are at the

railway station, you are irritated, but in the concert hall you pay money

to hear it!

BD: Have the composers

today forgotten about the public?

MR: [Laughs]

This is a little bit misleading because the composers I mentioned very seldom

considered the public. They wrote what they felt should be written.

Nowadays composers try to baffle people and to surprise people. I’m

now talking of people like Xenakis, and Eaton, and Cage. As far as I

remember, Cage said that if the art that is produced nowadays is any different

from life, then it is not a contemporary art. That is his opinion.

In times before ours, it was just the opposite. If something was the

same as it is in life, then it was not art. When I was a teenager,

I already knew that when I go to the theater, I want to know that I’m in

the theater. I don’t want to be someplace where it is ordinary life.

* *

* * *

BD: Tell me a bit

about the role of Wozzeck.

MR:

[Laughs] It is not easy to say a little bit in a short time.

Basically I will tell you that apart from the person I saw in 1930 in Vienna,

who had the advantage of Berg around, I haven’t found anybody who understood

the title role, or most roles, in Wozzeck

correctly. From what I’ve seen and heard, they all consider him as

a Dorftrottel [village idiot], a

fool, a real fool that is stupid and silly. Just the opposite is true.

He is a very intelligent, perceptible person. He is very sensitive

and is little educated, and knows nothing apart from what he heard.

Therefore he cannot understand most of the happenings around him. He

goes from the Captain to his common law wife, Marie, and then to the doctor,

and asks for explanations, and none of these people are capable to explain

the things which he asks. He asks what is it when the sun is so red

in the evenings. How come it’s like fire? How is it possible

that the toad stools are so regular? With such questions nobody can

guess, and they all think he’s going crazy... and at the end he does lose

his mind.

MR:

[Laughs] It is not easy to say a little bit in a short time.

Basically I will tell you that apart from the person I saw in 1930 in Vienna,

who had the advantage of Berg around, I haven’t found anybody who understood

the title role, or most roles, in Wozzeck

correctly. From what I’ve seen and heard, they all consider him as

a Dorftrottel [village idiot], a

fool, a real fool that is stupid and silly. Just the opposite is true.

He is a very intelligent, perceptible person. He is very sensitive

and is little educated, and knows nothing apart from what he heard.

Therefore he cannot understand most of the happenings around him. He

goes from the Captain to his common law wife, Marie, and then to the doctor,

and asks for explanations, and none of these people are capable to explain

the things which he asks. He asks what is it when the sun is so red

in the evenings. How come it’s like fire? How is it possible

that the toad stools are so regular? With such questions nobody can

guess, and they all think he’s going crazy... and at the end he does lose

his mind.

BD: Is he asking

these questions to expand his horizons and get more intelligence, or is he

just asking to survive?

MR:

No, no, no, he doesn’t go to school. He cannot afford it. He says immediately

at the beginning that he has not even the money to be moral, much less to

be educated. But the writer, Büchner, as well as Berg, identify

themselves with Wozzeck. They speak through Wozzeck. They certainly

don’t speak through Marie or the Captain or the Doctor, or to any of the

others. What they want to say, they say through Wozzeck. Who

would expect those people to identify themselves with an idiot? Despite

the trouble that he is in, although he cannot afford morality, he’s very

ethical and moral. After Marie has committed her sin, it is very strange

to him that it doesn’t show in her face. He said one should actually

be able to see that if somebody is not moral, or upright anymore. But

he cannot notice everything. “You look exactly

as you did before,” but he feels he has to be the arm

God, and that’s how he kills her. Then in the next scene, when people

are upset because they see he has a little bit of blood on him. They

don’t know from where it comes, so he says, “I must

have cut myself.” Then he says, “I

am murderer!” That somehow makes sense to him,

and then he goes and acts like any other murderer. Then he drowns.

He doesn’t drown willingly. He just goes into the water to wash the

blood off, and he drowns. There is a moment where his mind was ‘kaput’.

BD: You say that

Berg spoke through the character of Wozzeck. Do you find that most

great opera composers speak through one or another of the characters in their

operas?

MR: Oh, sure.

Verdi is a very simple case. He wouldn’t have made Traviata such a

good person if felt she was just a prostitute. Then he speaks through

Rigoletto. He does not identify himself with the Sparafucile, who is

a hired killer, or with the Duke; just with Rigoletto mainly, and then Gilda

to a certain extent.

BD: Is there ever

a case where a composer speaks through two of the characters in the opera,

rather than just one?

MR: Oh, yes, that

could be so. In the music which was written after the middle of the

past century, the thing can be much more complicated in the whole Wagner

business, and in Strauss. If you take Elektra, Orestes and Elektra are his

types.

BD: In Rosenkavalier, is it both Octavian and

the Marschallin?

MR: Well, Rosenkavalier I wouldn’t take that seriously!

[Both laugh] There are many things said through the Marschallin, and

through Octavian there are certain things, but this was all done by Hofmannsthal.

BD: You sang with

Strauss conducting?

MR: Yes.

BD: How was he

as a conductor?

MR:

I’ve never seen a better one and a more brilliant one. I saw him conduct

many times before I sang with him. He was the most brilliant musician

you can imagine. We don’t have such people around.

MR:

I’ve never seen a better one and a more brilliant one. I saw him conduct

many times before I sang with him. He was the most brilliant musician

you can imagine. We don’t have such people around.

BD: Was he as brilliant

with his own music as well as the music of others?

MR: His own and

the music of the others! I heard him do Mozart, Beethoven, and all

kinds of things.

BD: What made him

special, or was that just the spark of genius?

MR: Whatever he

did, he was a many-sided man. But he did it with such an ease, and

so brilliantly that if he would have been a better character as a human being,

he would have been a double for Beethoven. But unfortunately he was,

you know...

BD: So all of his

genius was concentrated in his music?

MR: In music he

was marvelous, but out of his music he didn’t have too much character.

You could leave out whatever you want from his works as long as you paid

the royalty. I heard him speaking that way when I was young.

I felt like strangling him because a composer should fight for humanity,

for human beings.

BD: Was there no

chance that he just wanted his music on the stage, even though it might have

been hacked to shreds?

MR: No, no, no,

no, no. It was both he and Stravinsky. The funny thing is both

have the first four letters the same. They were only after money.

[Pauses a moment] Well, I wouldn’t say ‘only’,

but the money was so important to them both.

BD: So they wrote

music for the money, rather than for their art?

MR: No, I wouldn’t

say that... I will give you an example. Stravinsky was directly

commissioned, but not with a contract, at Covent Garden, the Royal Opera

House. The manager said to him to write an opera in English and they

will perform it. Covent Garden performed his other operas in German,

of course, and also in translation, but he wanted one in English. So

Stravinsky wrote The Rake’s Progress,

but then he’s offered $2,000 more, and he gave the first performance in Venice!

His publisher told me that, so I knew it really happened that way.

As to Strauss, a rich American — I don’t know who it

was — paid him, as far as I remember, about $10,000

to copy another full score of Rosenkavalier.

BD: To make a hand-written

copy?

MR: Yes.

BD: And he did

it?

MR: And he did

it! I personally consider all Strauss’ music, especially his full scores,

whether it was manuscript or printed, to be like etchings. It’s fantastic.

For a musician, if you look at it, it is just so perfect. Somehow it

is a combination of an etching of a picture and music. It is fantastic.

You can see that it must sound beautiful as well. His handwriting is

something marvelous. Approximately a year before he died, I saw him

in the Tate Gallery in London, and we spoke. But then I watched him.

He was looking at the etchings as a painter would. He was fascinated

by the strokes of the pen. He studied it. I have never seen a

painter or a man who draws look at it with greater interest. He was

a marvelous mind.

* *

* * *

BD: Let us move

over to Wagner. You sang a number of his roles, and one in particular

— Amfortas — you have on your list that

you sang it in three different languages — German,

English and Serbo-Croatian.

MR: Yes, I sang

it first in Serbo-Croatian, then in German, and then in Bloomington in English.

For twenty years, always around Easter time, they had Parsifal. They stopped it about

ten or twelve years ago, or so.

BD: Is Parsifal

an opera or a religious drama?

MR: I don’t like

it as an opera. For me the best performance, or the one I enjoyed most,

was that one we had in Zagreb because there it was done with the intention

to be as it was in Bayreuth. We also had the intermissions as in Bayreuth.

It is a Catholic town, and in the chorus you could see that these people

considered that they don’t have to go to the church. They would just

do it there. It was a marvelous spirit, and as a teenager I went.

I was in the standing room for the students. It took six hours with

the intermissions, and I saw it twice in succession — Friday

and Sunday. You didn’t see the orchestra or the conductor because it

was covered just as in Bayreuth. In all the other towns where I saw

it or sang it, it was done like an opera.

BD:

That destroyed it a little bit?

BD:

That destroyed it a little bit?

MR: Oh, not necessarily.

The trouble is not with that. The trouble is that nobody performs Parsifal with the right tempi now. I haven’t heard it done

correctly for over fifty years. The overture, for instance, is done,

I would say, three time as fast as it should be.

BD: So the performance

should be very slow?

MR: Very slow.

I have demonstrated to my colleagues the difference in the very beginning

of the Grail motive, and after a few measures you are suddenly transformed.

BD: There are a

couple of recordings on the market now with Knappertsbusch which are very

slow. Is that slow enough?

MR: That could

be. Knappertsbusch was slow. He conducted also in Bayreuth.

I didn’t hear it but he was a marvelous conductor.

BD: Tell me about

the character of Amfortas. How did you see him?

MR: It is a part

which is composed just perfectly with the words to express everything, but

it is not musically or vocally easy. He is a very deep-felt person.

We had two performances in front of the Cathedral in Zagreb. In the

first row was the bishop, and in the second scene, as you know, I do take

the chalice and do a cross with it. I always did it so slowly and so

in the mood because it is a sacred work, not an opera. With that music

you can do it, but I have never seen it that way. Parsifal himself

also does it in the last act, but they never have the intention to do it

that way. I am a little bit different in this regard for many reasons.

I had marvelous teachers in my life, especially for music. When I studied

to be a conductor, one of our main teachers in the Academy, who taught us

orchestration said, “Don’t forget you are the representative

for the composer. You have to fight for what you think he intended.

You might misunderstand, but what you think he wanted and how he wanted the

music, you have to fight for it. If he is a dead composer you have

to do it doubly.” This made sense to me.

There was a famous man, the teacher of Zubin Mehta, named Swarowsky.

BD: Oh, Hans Swarowsky?

MR: Hans Swarowsky,

yes. He also worked on this with Strauss, and he translated everything

for Strauss. He was also very brilliant, but he just didn’t have

any character. We did several things together, including Don Carlo and Luisa Miller by Verdi, and he would leave

out one or two measures. So I said to him, “Who

are you to correct Verdi?” Once I had such a

fight with him we were not on speaking terms for a while.

BD: When a musician

on stage has a different idea than the musician in the pit, what happens?

MR: I would always

do what the conductors asked. I sang Rigoletto with many people.

In the third act, there is a marvelous scene where he sings to his daughter

she should be crying, piange, piange.

That is marked in the score as an eighth note at 60, which means one to one

second, and I wanted it in that tempo. Swarowsky said to me, “We

don’t have nerve today to do it so slowly.” I

said, “If you don’t have the nerve, don’t conduct it!”

[Both laugh] Sometimes we have to compromise, and sometimes

we have to rule with it, but you cannot fight a conductor. He’s the

boss in the performance. I did Rigoletto in Berlin with a conductor

who made up suggestions. He said to me, “Don’t

you think this is right?” I said, “For

me, the conductor is always right!” He was right,

of course. That is the basic rule. You cannot fight the stage

director. You can suggest, and you can try, but he has the last word,

and the conductor does, too.

BD: Are the stage

directors today perhaps having too many last words?

MR: I don’t know

any stage director like that. People like that should not be directing...

with very few exceptions, and the exceptions are always when people who were

singers became stage directors, then they do the same thing that they did,

so that is good. For instance, here (at Indiana University) Rossi-Lemeni did

several things, and he did very well. But the so-called stage directors

always want to be original, and they always disregard intentions of the composer.

You can see this, for instance, very well in works like Carmen, which are so simple. They

try to make Don José as bad as he is in the novel — which

means he is a murderer and a deserter — but Bizet did

not put that to music. He didn’t make him at all that character.

Just think of the duet with Micaëla. This is not such a character,

and nowhere in the dialogue is he such a person.

BD: Where do we

draw the line between breathing new life into a piece and going too far?

MR: That’s what

I would like to know, but I don’t know when was the last time I personally

had contact with a stage director I could agree with or accept. I will

tell you of one very well-known stage director who came once to stage an

opera here. He’s with the Met and all the big houses. I don’t

want to say his name. I was told how marvelous he is, and he was a

very nice person. I met him and spent a marvelous evening with him.

That was very good, but when I went to the rehearsal I couldn’t believe my

eyes. It was a simple opera called La Bohème, and in the last act,

for instance, what Musetta should be saying to Marcello, he made her say

to Schaunard! Even the snow was in the beginning of the second act

instead of the third act. If you ask me, there was not one single minute

which was correct.

BD: That’s too

bad.

MR: And this is

one of the leading stage directors. Mostly it comes because they want

to do it differently, and they want to be original. Sometimes probably

they misunderstand, and they want to put something in a work that isn’t there.

BD: But I assume

you don’t feel the work should always be staged exactly the same way, slavishly

adhering to one concept?

MR: No, not at

all. We had rehearsals for Wozzeck

in New York, at the Met. I had sung it before in London and Buenos

Aires, and so on. The stage director was Herbert Graf, who was a Viennese

and very intelligent man who knew Berg personally. In one scene, Wozzeck

comes to the window, and Marie tells him to come in. He says he has

no time, and then he goes. Graf made Wozzeck come into the room while

she still saying to come in. Hermann Uhde sang the performances (along

with Eleanor Steber

as Marie), and he did what Graf asked. However, I stayed at the window.

Erich Kleiber was the conductor and he helped me enormously. He knew

the work better than Berg himself musically in every regard. He explained

to me many things when we first did it. He was my conductor when we

did gave it for the first time at Covent Garden in 1952, and he was the original

conductor in 1925. So I asked Kleiber what I should do, and he said

to do it correctly. Suddenly when I did it, Graf said, “Now

it makes sense to me.” You see, if you don’t

do it right, it doesn’t make sense, but there are several ways of doing it

right.

BD: Was it being

sung in English?

MR: That was done

in English, yes.

* *

* * *

BD: Do you feel

that opera works well in translation?

MR: Absolutely,

if the translation is good. It is always important that the audience

understands it, and above all that the singer understands it. Immediately

after the War, we had Aïda

in Vienna in Italian. That was the only opera they did in the original.

Since about 1960 they do most operas in the original, but before that everything

was done in the language of the country. So first of all, the Radames

had such bad pronunciation that it was impossible, and of course he didn’t

understand one word he was singing. He could emphasize the wrong word

very easily. On the other hand, I had the experience when I sang it

in one language and a guest sang it in another, that can be also very awkward.

I remember a funny instance in Butterfly.

There was a guest, Dusolina Giannini, and she sang in Italian. So at

one point I asked what day is today, and she asked if I had an orange because

the translation didn’t go at the same time. [Both laugh] In London

we had Tosca in English. At

that time, they did everything in English. Only during the June Festival

Wagner was done in German, but now they do everything in the original.

We had once a guest Tosca who sang in Italian, so I sang all our scenes in

Italian because Scarpia is very much with Tosca. Whenever we were together

I sang with her in Italian so as not to say something and then have her answer

something different. I thought it was better that way.

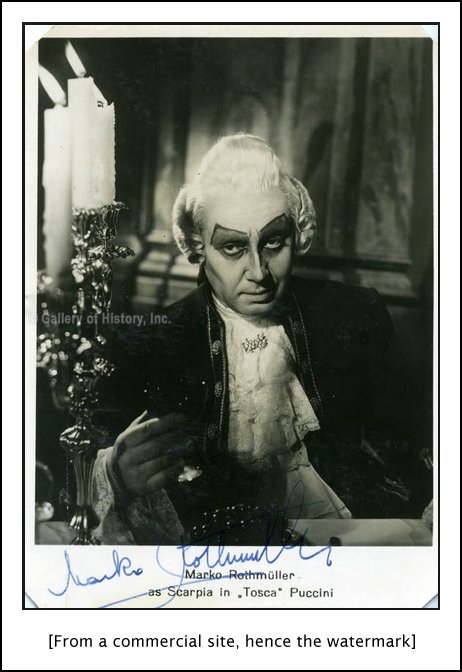

BD: How evil is Scarpia?

BD: How evil is Scarpia?

MR: He’s very evil,

but somehow everybody likes him. I can be particularly evil as Scarpia.

In the first act when I come on the stage, the fear and the audience being

scared is so translated that you can feel it on the stage. Nobody is

other than tense, and on the stage certainly you understand that. In

the second act I preyed very much in this sadistic way. I’m so nervous

all the time when I’m interrogating and not getting the answer I want, that

when Tosca suddenly bursts out where Angelotti is you can see how my full

tension is gone. I’m suddenly relaxed! At first you see how he

tries to be very dangerous, and that’s very important. But everybody

likes him, and that is shown in a funny thing. We had Tosca in London, and Hilda Zadek sang

the title role. There was an elderly gentleman who was a great admirer

and friend of her, and one evening after a performance, Zadek said it was

her birthday and there was to be a little party. So we went, and there

was that gentleman. He was a Hungarian, a very sweet person.

Later on we were friends with the family, but suddenly, at that first meeting

he said (with amazement) that I was a very nice man! He always thought

that I was such a horrible police chief as Scarpia. [Both laugh]

BD: When you’re

on the stage, how much are you portraying a character and how much do you

become the character?

MR: I am not myself

anymore. I become the character. When I was a student, I heard

Lotte Lehmann. Her brother was one of our teachers in the Conservatory,

and one day she came for a visit. Everybody sang this and that, and

then he asked her what helps her when she’s portraying something. She

said, “When I am portraying something, I always try

to imagine what this person will do, and how this person would act and react.”

That was still at the time when I didn’t want to become a singer. I

never thought I would become a singer, but I already sang certain things

in this opera workshop. I felt that this idea was wrong, but later,

of course, I came to it. I’m never thinking of the person. When

I sing The Barber of Seville, I

am the mischievous young boy, and I act as I would act when I’m him exactly.

When I’m Scarpia, I’m terrible. There was another opera where I have

to strangle the tenor [probably Il

Tabarro, also of Puccini].

We didn’t have stage rehearsals because we didn’t have enough time, and suddenly

comes the dress rehearsal. The stage director at that time, who was

a good one, said that we hadn’t rehearsed that strangling. So I jokingly

said to him, “You, a Swiss, want to teach me, a Yugoslav,

how to strangle a person???” [Both laugh]

Of course, I was trying to do it especially well and satisfactory.

When I strangled him, I didn’t really strangle him, but on my face you could

see a strangler! Even if the part is something I wouldn’t like, the

moment I’m on stage I am that person.

BD: Then how long

after the performance does it take for you to let go of that character.

MR: The moment

I’m off the stage, probably. There are some parts which for hours before

and hours later I am the same person. My colleagues, the stage hands

and so on used to watch me when I was doing Rigoletto. I’ve never seen

a Rigoletto who is immediately a Rigoletto. I’m Rigoletto, even behind

the stage. Otherwise, how can it come across authentically?

BD: When you leave

your dressing room, that’s when you become this character?

MR: The moment

I put the costume on, certainly. When I was a young singer, a very

esteemed critic and musicologist in Zurich, who also taught at the university

and was a known author of books about Wagner and so on, once came to me and

asked, “Tell me, Mr. Rothmüller, how are men with

your background not bored or irritated doing the same parts over and over

again?” I was a young man, only twenty-seven

years old at that time, and I said to him, “I never

sing or do the same part twice.”

BD: It’s always

new?

MR: Yes.

I have spoken to many artists and conductors, and they all have the same

attitude — it’s never the same. It’s always new

unless you become a mechanical person.

BD: So that is

the heart of the characterization?

MR: Yes.

Once I had a terrible time because we had several Traviata performances in less than two

weeks. This is a part which is beautiful to sing. It is not easy

to sing, but as an acting part there is not much development. So it

doesn’t need such a great investment of concentration. So it happened

after a few evenings, after the second act the conductor comes on stage,

and asked if I could see him. I didn’t even know. It became so

mechanical because there were too many performances in succession.

That can happen. But while I was singing, obviously he didn’t notice

anything.

BD: This is really

more from the heart than technique?

MR: Absolutely!

Technique is only the means you use. It’s a tool. The more technique

you have, the more you can use it, but I have never found it so that you

could see it in a trained singer. The General Manager in Zurich, who

was a great admirer of mine, said to me often, “For

you singing is nothing. You just sing.”

They all thought that I just open my mouth and can sing, and I don’t have

to use technique. In truth, I never sing one note without knowing how

and why, but I don’t show it! It must look almost as if I would speak.

That’s also what I try to teach. If a blind person hears you, he must

always hear a very even melody. If a deaf person notices that you are

singing, he must never know when you’re singing low notes or high notes.

You can see it all on the faces of so many singers. For instance, with

opera performances on the television, you can turn off the sound but you

can still know when he or she is singing high notes. [Bruce laughs]

BD: It’s all in

the face?

MR: Yes, and it’s

not supposed to be. It has nothing to do with it. The high note

is not made by the face. It’s not made by the mouth. It is made

in your larynx, in your voice box.

BD: And supported

by the diaphragm?

MR: Exactly.

* *

* * *

BD: Let me ask you about another composer

— Heinrich Sutermeister.

BD: Let me ask you about another composer

— Heinrich Sutermeister.

MR: He’s a very

nice young man... at that time he was a young man!

BD: Was he a good

opera composer?

MR: Well, I didn’t

find him too original, but he was a very capable composer, and what he wrote

worked on the stage. I would say he was much like Menotti, only I liked

him better than Menotti.

BD: What about

Benjamin Britten?

MR: There you are

in a different level. That was a marvelous, marvelous musician, marvelous

composer, marvelous man, but he had also his strange characteristics.

He didn’t consider Brahms to be a good composer. That can happen, although

he had something in common with Brahms. I just realized that Brahms

always played his things for his friends, and they would make suggestions

but he would change nothing. Britten and I became very good friends,

and his publisher told me he could sell The Rape of Lucretia to many theaters

if it had a normal orchestra. The work is written only for thirteen

instruments. Once after a performance when we were in Aldeburgh, we

were talking, and Britten was in marvelous mood. So I said that Dr.

Hawkes told me that he should make a version for a normal orchestra.

He was suddenly so angry! He said that he cannot do it. It’s

only for this group, and he wouldn’t change it. You know, Berg did

write Wozzeck for quite large orchestra,

and then he made version for a small orchestra.

BD: So there are

two versions?

MR: Yes, one with

a smaller orchestra. When I did it in New York at the City Opera, we

did it with this version. I believe all the woodwinds were in twos

and not threes, but then the sound is always the same. I didn’t notice

any difference.

BD: You’ve given

a lot of ideas to think about, and you continue to give a great deal to your

students.

MR: I’m not teaching

anymore unfortunately, although I like to teach. We will have this

masterclass, but that’s only one week or so.

BD: But you’ve

given so much through your many performances on stage, and thousands of lessons

to students. Do you feel that your students can carry on the flame

that you had?

MR: Many do.

I wouldn’t know any exceptions to those who carry on the morals, or the ethics

that I instilled in them, even if they are not all performers. That’s

my Credo.

BD: I certainly

appreciate you taking the time this afternoon to talk with me.

MR: Thank you very

much. I enjoyed it.

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on May 18, 1985.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1993 and 1998. This transcription

was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My

thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her

help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was

with WNIB,

Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until

its final moment as a classical station in February

of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various

magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues

his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information

about his work, including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus a full list of

his guests. He would also like to call your attention

to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

MR: Oh, they liked that here. They like to

have an active artist. We have Starker, for instance,

and Pressler, and

many people who concertize all over the world.

MR: Oh, they liked that here. They like to

have an active artist. We have Starker, for instance,

and Pressler, and

many people who concertize all over the world. MR: Yes, I did. At that time I didn’t even

intend in the slightest to ever become a singer. During the time I

was in Vienna — before I came to him — I was

already a paid conductor of a choir. But before that, I also conducted

instrumentalists, and so on. My oldest brother, who took care of us

because we didn’t have a father anymore at that time, said I should also

take voice lessons because a voice teacher had said it would be a crime not

train my voice. So I had to do it, because otherwise I couldn’t understand.

It was only when I was with Berg for about three years that people heard

me, and I suddenly had success as a young singer. Then I figured if

I tried as a singer and didn’t succeed, I could always turn to conducting,

which I did. I conducted orchestras and my own compositions during

my life several times. Even in the last ten years in Bloomington, I

wrote for a play with music, and I conducted it myself. But if I started

to sing I didn’t succeed or I didn’t like it, then it is very difficult because

a voice is an instrument which you have to maintain.

MR: Yes, I did. At that time I didn’t even

intend in the slightest to ever become a singer. During the time I

was in Vienna — before I came to him — I was

already a paid conductor of a choir. But before that, I also conducted

instrumentalists, and so on. My oldest brother, who took care of us

because we didn’t have a father anymore at that time, said I should also

take voice lessons because a voice teacher had said it would be a crime not

train my voice. So I had to do it, because otherwise I couldn’t understand.

It was only when I was with Berg for about three years that people heard

me, and I suddenly had success as a young singer. Then I figured if

I tried as a singer and didn’t succeed, I could always turn to conducting,

which I did. I conducted orchestras and my own compositions during

my life several times. Even in the last ten years in Bloomington, I

wrote for a play with music, and I conducted it myself. But if I started

to sing I didn’t succeed or I didn’t like it, then it is very difficult because

a voice is an instrument which you have to maintain. MR:

[Laughs] It is not easy to say a little bit in a short time.

Basically I will tell you that apart from the person I saw in 1930 in Vienna,

who had the advantage of Berg around, I haven’t found anybody who understood

the title role, or most roles, in Wozzeck

correctly. From what I’ve seen and heard, they all consider him as

a Dorftrottel [village idiot], a

fool, a real fool that is stupid and silly. Just the opposite is true.

He is a very intelligent, perceptible person. He is very sensitive

and is little educated, and knows nothing apart from what he heard.

Therefore he cannot understand most of the happenings around him. He

goes from the Captain to his common law wife, Marie, and then to the doctor,

and asks for explanations, and none of these people are capable to explain

the things which he asks. He asks what is it when the sun is so red

in the evenings. How come it’s like fire? How is it possible

that the toad stools are so regular? With such questions nobody can

guess, and they all think he’s going crazy... and at the end he does lose

his mind.

MR:

[Laughs] It is not easy to say a little bit in a short time.

Basically I will tell you that apart from the person I saw in 1930 in Vienna,

who had the advantage of Berg around, I haven’t found anybody who understood

the title role, or most roles, in Wozzeck

correctly. From what I’ve seen and heard, they all consider him as

a Dorftrottel [village idiot], a

fool, a real fool that is stupid and silly. Just the opposite is true.

He is a very intelligent, perceptible person. He is very sensitive

and is little educated, and knows nothing apart from what he heard.

Therefore he cannot understand most of the happenings around him. He

goes from the Captain to his common law wife, Marie, and then to the doctor,

and asks for explanations, and none of these people are capable to explain

the things which he asks. He asks what is it when the sun is so red

in the evenings. How come it’s like fire? How is it possible

that the toad stools are so regular? With such questions nobody can

guess, and they all think he’s going crazy... and at the end he does lose

his mind. MR:

I’ve never seen a better one and a more brilliant one. I saw him conduct

many times before I sang with him. He was the most brilliant musician

you can imagine. We don’t have such people around.

MR:

I’ve never seen a better one and a more brilliant one. I saw him conduct

many times before I sang with him. He was the most brilliant musician

you can imagine. We don’t have such people around. BD:

That destroyed it a little bit?

BD:

That destroyed it a little bit?

BD: How evil is Scarpia?

BD: How evil is Scarpia? BD: Let me ask you about another composer

— Heinrich Sutermeister.

BD: Let me ask you about another composer

— Heinrich Sutermeister.