Roberta Peters was born on May 4,

1930, in New York City. Despite their modest means, her parents, Ruth (Hirsch),

a milliner, and Sol Peterman, a shoe salesman, arranged the private tutoring

in language, piano, drama, and ballet that made possible their only child’s

remarkable career. In 1949, after hearing her audition in the studio of her

teacher, William Herman, the late renowned impresario Sol Hurok took Peters

under his wing, despite her youthful nineteen years and complete lack of

performing experience. Hurok arranged her audition for Rudolf Bing, then

general manager of the Metropolitan Opera, which led to a contract to appear

as the Queen of the Night in Mozart’s The

Magic Flute. As fate would have it, the young singer was called upon

several weeks earlier, on November 17, 1950—with just six hours’ notice—to

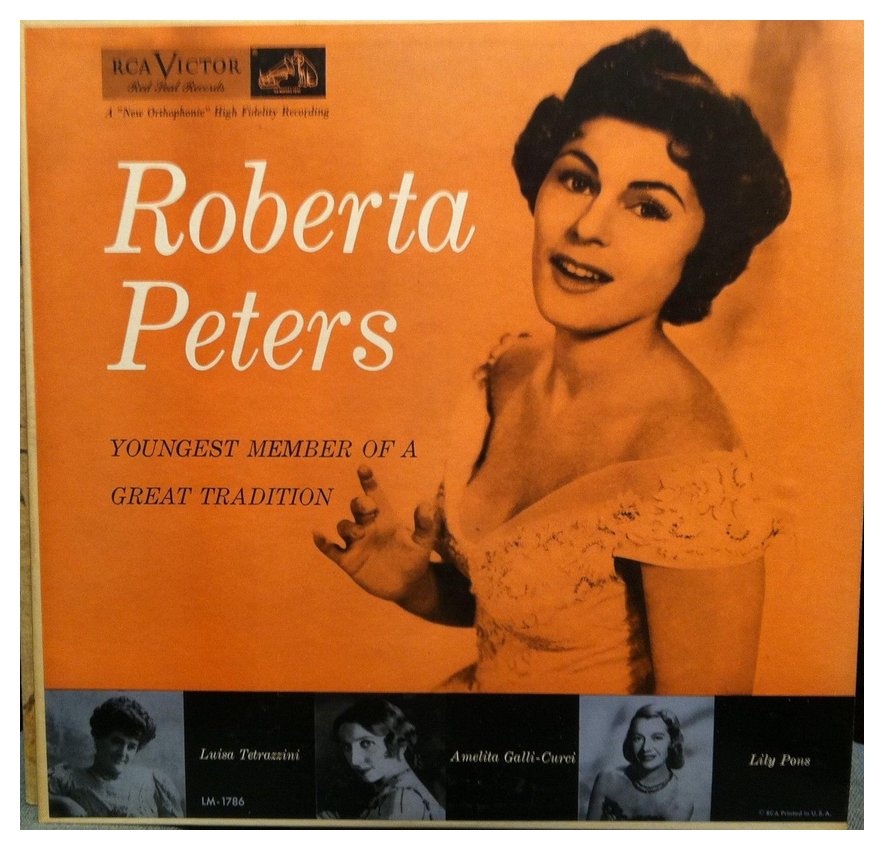

replace an indisposed colleague as Zerlina in Mozart’s Don Giovanni. Since then, Peters has

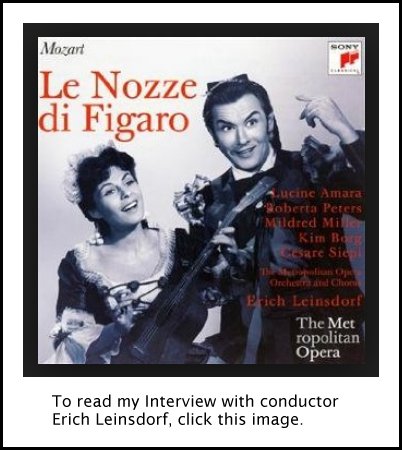

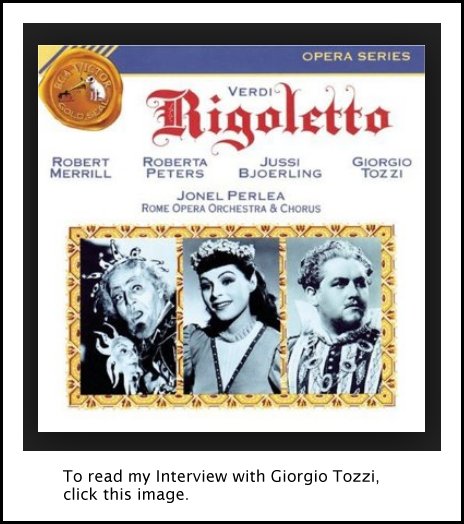

earned acclaim singing such coloratura “leading ladies” as Lucia in

Lucia di Lammermoor, Gilda in Rigoletto, and Rosina in The Barber of Seville, as well as roles

in other styles: Mozart’s Zerlina, Susanna, Despina, and Queen of the Night;

Richard Strauss’s Zerbinetta; Johann Strauss’s Adele; Donizetti’s Adina and

Norina; and Menotti’s Kitty, a role she created for the American premiere

of The Last Savage at the Metropolitan

Opera. She also added roles in romantic operas, including La Traviata and La Bohème, to her repertoire,

with much success. In fact, Peters has achieved the longest tenure of any

soprano in the history of the Metropolitan Opera. A performer in fifty-seven

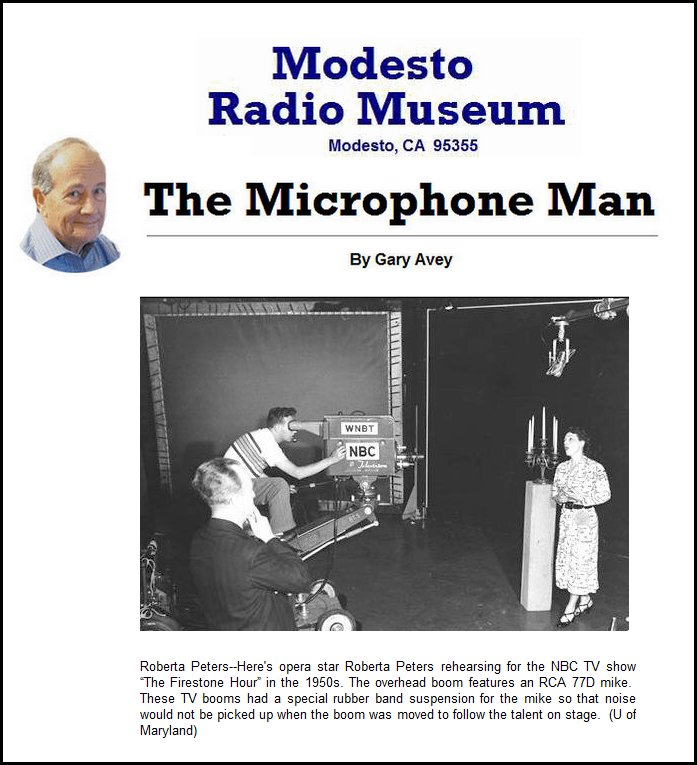

Texaco radio broadcasts heard live from the Met, she also made an unprecedented

sixty-five appearances on the Ed Sullivan television show.

Beyond her success on American stages, the renowned singer has

performed in operas, concerts, and recitals with some of the world’s greatest

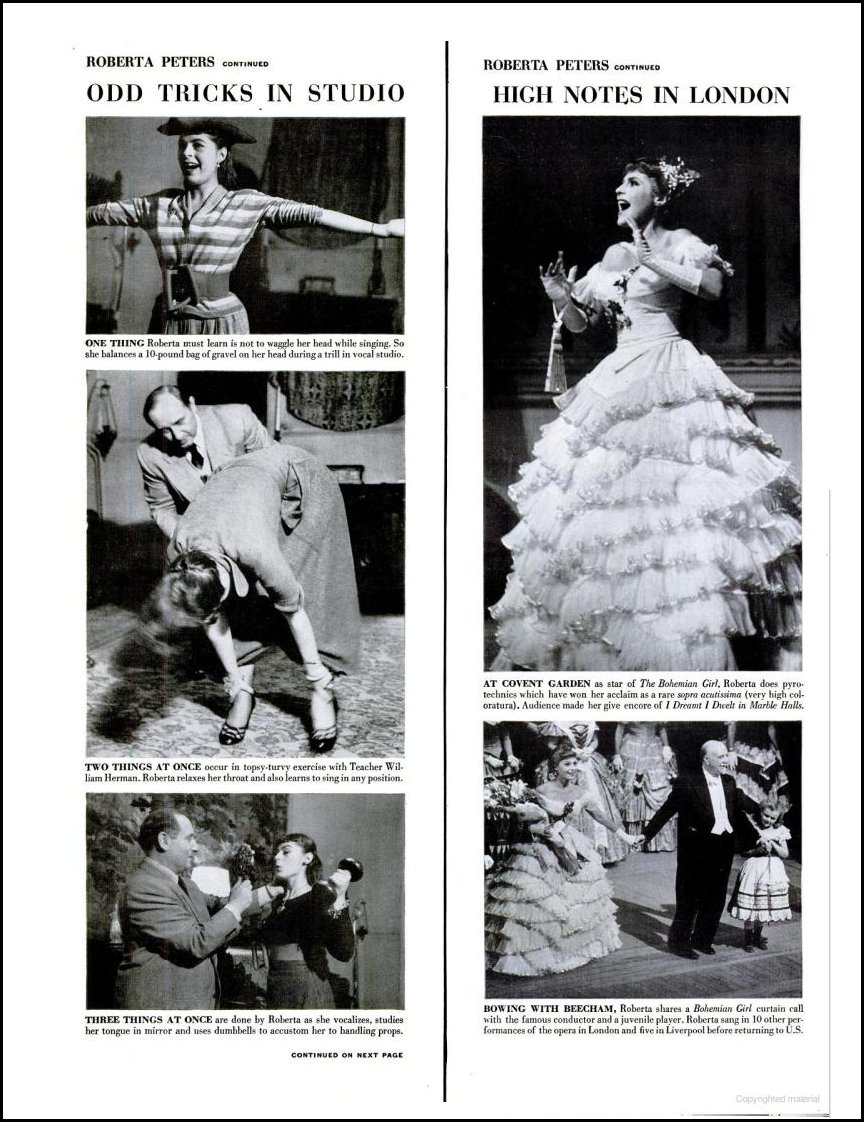

conductors and orchestras. Peters made her European debut as the Bohemian Girl under the direction of

Sir Thomas Beecham at London’s Covent Garden. Her performance as Queen of

the Night under the direction of Karl Böhm at the Salzburg Festival

won high praise, as did her appearances at the Kirov Theater in Leningrad

and the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow, where she became the first American-born

artist to receive the coveted Bolshoi Medal.

Beyond her success on American stages, the renowned singer has

performed in operas, concerts, and recitals with some of the world’s greatest

conductors and orchestras. Peters made her European debut as the Bohemian Girl under the direction of

Sir Thomas Beecham at London’s Covent Garden. Her performance as Queen of

the Night under the direction of Karl Böhm at the Salzburg Festival

won high praise, as did her appearances at the Kirov Theater in Leningrad

and the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow, where she became the first American-born

artist to receive the coveted Bolshoi Medal.

With varied repertoire ranging from baroque masterworks of Bach and Handel

through German lieder, French, Italian, Spanish, and English art songs, and

American folk songs, Peters has presented recitals and master classes throughout

the world. In 1979, she traveled to the People’s Republic of China. Tours

of Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan followed in 1987, 1988, and 1990.

Peters has also been a popular recitalist and master teacher on the American

college and university scene. Her successes there—and throughout the world—have

been acknowledged with the awarding of honorary doctorates from Lehigh, St.

John’s, Rhode Island and Richmond universities, as well as from Elmira, Westminster,

Colby, New Rochelle, and Ithaca (where she serves as honorary trustee) colleges.

While maintaining a schedule averaging forty concert appearances each year,

Roberta Peters also lent her efforts to a variety of social causes. She served

as chairwoman of the National Cystic Fibrosis Foundation for several years

and has appeared in concerts benefiting AIDS research. She has taken an active

role in efforts to promote government funding for the arts and serves on

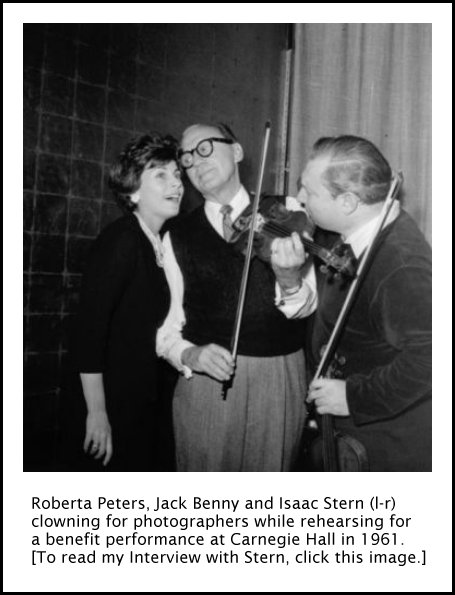

the boards of the Metropolitan Opera Guild and the Carnegie Hall Corporation.

She is also an artistic advisor on the boards of the Kravis Center for the

Performing Arts and the Jupiter Theatre in Florida.

President John F. Kennedy first invited Peters to appear at the White House

and she has appeared to sing for every president since. In 1991 she was appointed

by President Bush to a five-year term on the National Council on the Arts.

President Clinton awarded Peters the 1998 National Medal of Arts, and two

years later, New York City Mayor Giuliani awarded her the Handel Medallion,

a tribute to individuals who have enriched the city’s cultural life. Roberta

Peters has made Israel and music of Jewish interest an important priority

in her life. Although she received no formal Jewish education, she learned

to speak Yiddish as a child from her grandmother, who spent most of the year

living with the Peterman family while her husband served as maitre d’ at Grossinger’s

Hotel in the Catskill Mountains, and with whom the young Roberta attended

an Orthodox synagogue. Yiddish folk songs have always been an integral part

of Peters’ many performances for synagogue audiences and other Jewish groups.

She has been a prominent spokesperson for many Jewish causes, including the

Hebrew University, where she established the Roberta Peters Scholarship Fund,

and Israel Bonds, and has served on the board of the Anti-Defamation League.

Peters has appeared often in Israel, performing to benefit her endowed scholarship,

and for soldiers in 1967, when she and her colleague Richard Tucker were

caught in Israel during the Six-Day War. In addition to performing contemporary

works by leading composers Aram Khatchaturian, Paul Creston, and Roy Harris,

Peters appeared in the 1973 Carnegie Hall premiere of Darius Milhaud’s Ani

Ma’amin (with libretto by Elie Wiesel) and in the 1982 premiere of Abraham

Kaplan’s Kedushah Symphony. In 1992 she received Bnai Brith’s Dor L’Dor Award,

the organization’s highest honor, and in 1997, the National Foundation of

Jewish Culture awarded her its Jewish Cultural Achievement Award in Performing

Arts for “her talent, her charm, and her commitment to the arts as well as

to the Jewish people.”

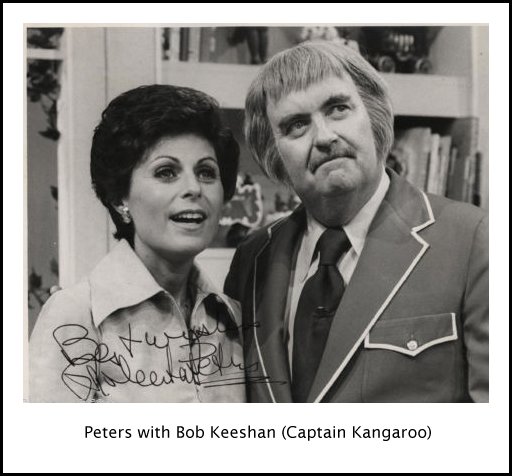

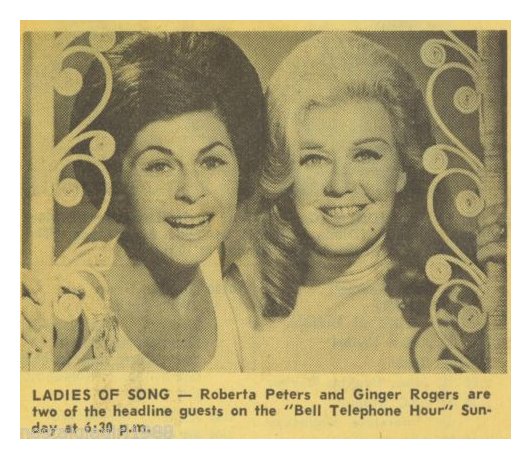

Although opera has played the defining role in her artistic life, Peters

has also performed in operetta, musical comedy and film. Early in her career

she played a feature role in the movie Tonight

We Sing (1953), and she returned to film to appear in City Hall in 1996. An avid tennis player,

Peters has also appeared in several celebrity tournaments.

-- Text from a biography by Marsha

Bryan Edelman on the Jewish Women's Archive website.

[Photos added for this website presentation.]

|

BD: How has opera changed in the last thirty years?

You made your debut in 1950...

BD: How has opera changed in the last thirty years?

You made your debut in 1950...  BD: And some go too fast.

BD: And some go too fast. BD: As a singer, how do the different houses

affect your vocal performance, when you’re in a smaller house or a larger

house? Do you have different techniques, or do you just rely on the

technique you have and hope that you’re heard?

BD: As a singer, how do the different houses

affect your vocal performance, when you’re in a smaller house or a larger

house? Do you have different techniques, or do you just rely on the

technique you have and hope that you’re heard? BD: Do you enjoy modern operas?

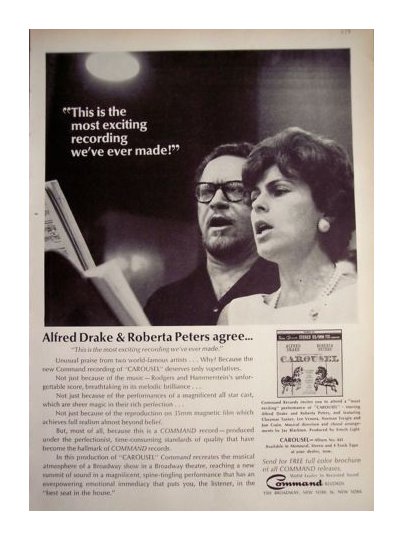

BD: Do you enjoy modern operas? BD: Do you enjoy making recordings?

BD: Do you enjoy making recordings? RP: Well, the orchestra had not really read much

of my music before. They were wonderful, really. They had great patience,

and that was very important. But the conductor, too, hadn’t done this

music that much. So I had to tell him how I do it. He was very

much with me, which is nice.

RP: Well, the orchestra had not really read much

of my music before. They were wonderful, really. They had great patience,

and that was very important. But the conductor, too, hadn’t done this

music that much. So I had to tell him how I do it. He was very

much with me, which is nice.  BD: But most of those are songs rather than arias?

BD: But most of those are songs rather than arias? RP: No. I wouldn’t do anything like that.

I used to do some of the summer operettas and shows, and I was offered Kiss Me Kate, but I would never do that.

It’s a beautiful show, but it is a lot of screaming and running and doing

all that kind of thing. That’s not for me. I’ve done King and I and The Sound of Music and Merry Widow. Those are the things

I can do. That’s another thing. You have to know the works, and

if you don’t know, then you have to get good advice from somebody else who

knows what’s right for you.

RP: No. I wouldn’t do anything like that.

I used to do some of the summer operettas and shows, and I was offered Kiss Me Kate, but I would never do that.

It’s a beautiful show, but it is a lot of screaming and running and doing

all that kind of thing. That’s not for me. I’ve done King and I and The Sound of Music and Merry Widow. Those are the things

I can do. That’s another thing. You have to know the works, and

if you don’t know, then you have to get good advice from somebody else who

knows what’s right for you. BD: But that comes more out of the operatic tradition.

BD: But that comes more out of the operatic tradition. RP: Yes, I think you do.

RP: Yes, I think you do.